Introduction

Russia’s economy has demonstrated impressive resilience in the face of Western sanctions, so far. Forecasts of gross domestic product (GDP) downturn have been consistently revised on the upside, and inflation, though high, is lower than in Italy and in line with global trends.

This resilience stands in stark contrast to the consensus in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that unprecedented Western sanctions would at least give the Kremlin pause. While observers knew the export controls on key technologies and inputs would take time to bite, it was hoped that the financial sanctions and the blocking of the Central Bank’s reserves would be so disruptive that Russia just might reconsider. Many, including this author, fell for this kind of reasoning.1

However, the factors that have spared Russia an immediate financial crisis and allowed it to finance the war are relatively few, and not guaranteed to remain in place. Many good recent reports delve deeper into production and how export controls are running down inventories and damaging entire sectors. This report takes a different tack by looking at the Russian government and the Central Bank’s management of oil and gas income, and how they’re preparing for the years to come. Difficulties are likely to compound as income falls and spending increases.

Official databases now feature obvious and deliberate gaps. The Central Bank of Russia (CBR) stopped publishing important time series relating to reserves at the onset of the war, while the customs authorities stopped updating the detail of trade volumes. Yet, there is still enough available in terms of raw data—and via official reports—to get a reasonable idea of what is going on.

Why? Russia may be waging a senseless war in Ukraine, but it also wants to be taken seriously by financial stakeholders, both internal and external. The lost access to Western finance has affected banks’ profitability, so it is vital that they convince Chinese and other banks that the Russian financial system remains robust enough.2 There are now fewer independent data available, as Western financial institutions and ratings agencies are leaving Russia. This forces the institutions to provide just enough transparency, while depriving sanctions-wielding countries of the information they want to test the effectiveness of their own policies.

So, it is up to us to use the data we can access, but use them with a critical eye.

I. Trade and the strong ruble

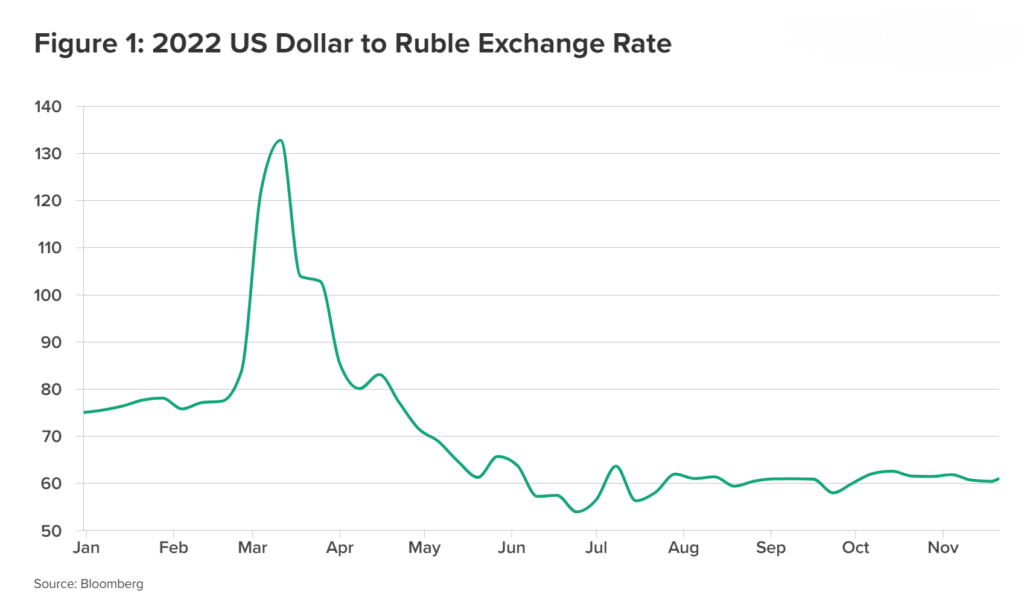

On a visit to Poland one month after Russia launched its invasion, President Joe Biden bragged that the unprecedented package of sanctions had reduced the ruble “to rubble.” While sell-offs had indeed caused the ruble to depreciate strongly in late February and early March, the picture was already quite different by the time Biden made his speech on March 26.

The story behind the ruble’s rapid recovery is one of good crisis management and good luck, in equal measure.

The Central Bank’s initial firewall response forced financial actors inside Russia to wait it out. In her February 28 press conference, dressed entirely in black, Governor Elvira Nabiullina announced a series of measures that went against her long-standing principles of free-flowing capital and a reasonably transparent lending system, all to serve the immediate priority of compensating for lost hard-currency reserves and keeping banks’ balance sheets in the black.

The key interest rate was slammed up to 20 percent, providing an immediate incentive against runs on banks. Eighty percent of export income would be forcibly converted into rubles. Now reduced to 50 percent, this measure still grants the Central Bank access to dollars and euros, which it can then lend to banks to meet their liabilities or to firms to import goods. It also stemmed the flow of foreign exchange leaving the country by limiting nonresident investors’ ability to withdraw capital and Russians’ ability to take cash across the border. Finally, the bank loosened auditing requirements for private banks, allowing them not to update or publish asset valuations.3 This measure was finally phased out on October 1, but some capital controls will remain in place until the end of 2023 at the earliest.4

These highly unorthodox measures, of which observers were skeptical at the time, succeeded in keeping the Russian financial system in suspended animation for long enough before the dominant factor behind the ruble’s recovery came into play: a bumper current-account surplus powered by high oil and gas prices and lower imports.5

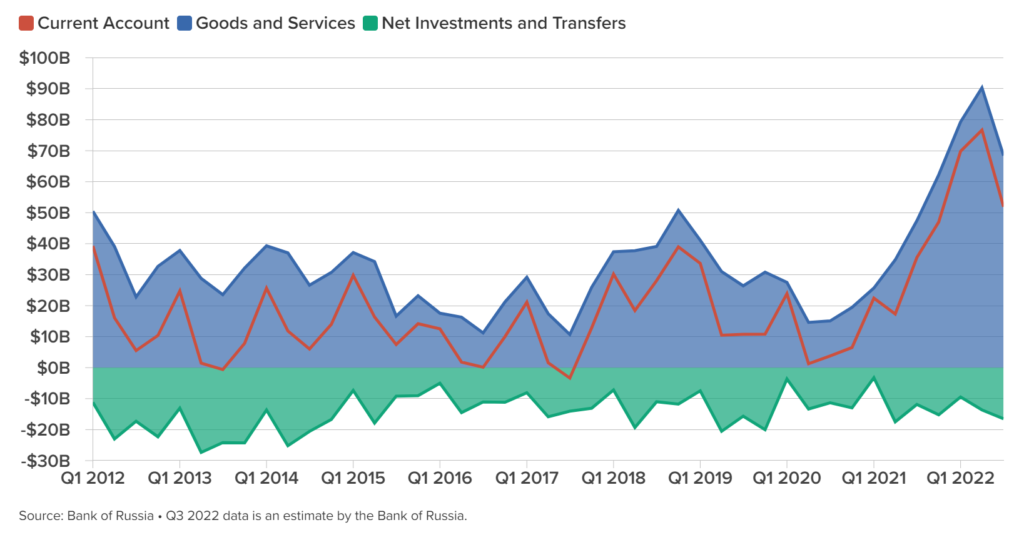

Russia’s current account reached a record high of $76.7 billion in the second quarter of 2022. It remained well above historical trends in the following period, between July and September, at $51.9 billion. Figure 2 shows clearly just what kind of an outlier this year has been.

Figure 2: Quarterly Russia Current Account Balance

While still high, the current account surplus has fallen as Western oil importers have sought to diversify away from Russia, and as Russia has reduced the volume of its gas deliveries to Europe on its own initiative. There is also a secondary, but underappreciated, dynamic at play in net investments and net transfers, which are falling. In other words, Russians leaving the country are taking their savings with them, and Western firms are slowly beginning to divest despite the remaining constraints on capital flows.

The relationship between a positive current account and currency appreciation is easy to grasp. Higher commodity prices have meant that more US dollars and euros have flown into Russia and pushed up demand for domestic currency. For the money market to clear, either the interest rate or the exchange rate must increase. But the interest rate has been dropping step by step since the Central Bank’s initial hike to 20 percent just after the invasion. The exchange rate alone is able to reflect higher demand for rubles.

In late March, much was made of the Russian government’s decision to demand that “unfriendly”—meaning sanctions-wielding—countries pay for energy imports in rubles. This announcement is remembered as a turning point for the ruble, and it is true that the market anticipation of more demand for the currency was an early spark to its recovery.6 However, the policy has little to no impact on balance-of-payments dynamics. About twenty European gas-buying firms have opened ruble accounts with Gazprombank, and swap their dollars and euros for rubles there. Russia’s energy exports are the reason it has been able to access sufficient hard currency for its immediate needs since the beginning of the war, in spite of the much-publicized blocking of Central Bank foreign-exchange (FX) reserves.

Strong ruble and sanctions skepticism

The ruble’s strength and Russia’s bumper export income have caught the public’s attention in countries that decided to wield sanctions against Russia. Their own governments initially presented the ruble’s initial tumble as evidence of the sanctions’ effectiveness, so it is only natural that voters should be puzzled by the current situation.

The governments concerned should have seen this coming. Uncertainties over supply due to the war were going to raise prices. And energy exports are so important to the Russian economy and government income that oil and gas prices impact the relative prices of Russian goods, the business cycle and trade balance, and even interest rates. Gas and, especially, oil prices influence all the determinants of the ruble exchange rate, in the short, medium, and long runs.

This author argued in May that, while the ruble exchange rate is not a good indicator of the health of the Russian economy, it shouldn’t be ignored by Western policymakers either.7 It is, first and foremost, a symptom of oil and gas exports being Russia’s economic lifeline. To a limited, but not insignificant, degree, a strong ruble also allows firms and consumers who can afford them to secure embargoed goods and technology, at a significant premium. New iPhones are available in Moscow for just under 175,000 rubles ($2,900). The same model is available for $1,599 in the United States.

It is true that ruble trade volumes are much smaller than they were before the war, so the exchange rate is no longer an accurate or insightful indicator of value.8 The Urals index has fallen from peaks above $100 to below $70 without much of a depreciating effect on the ruble. Measures introduced in late February, like the forcible conversion of export income and capital controls, even temporarily increased demand for black-market exchanges, with rubles being sold at a lesser rate to the dollar.9

A strong ruble exacerbates the risk of “Dutch disease,” especially when combined with Western embargos on new technologies. The Russian economy has little incentive to diversify, and will not be competitive in doing so anyway.

Sanctions-wielding countries are struggling to communicate this complexity to the public effectively. This is understandable. Other familiar economic indicators have also outperformed expectations since the beginning of the war. GDP is only expected to slide a few percent year on year, instead of the 15 to 20 percent initially forecast. Year-on-year inflation is high, but lower than in Italy. Prices have actually been falling month on month since the initial spike in the second quarter (Q2).

So, it’s important to dig deeper and look into what the Russians are still able to do with their export income, and why the domestic economic outlook for 2023 is bleak.

II. Budgets and long-term savings

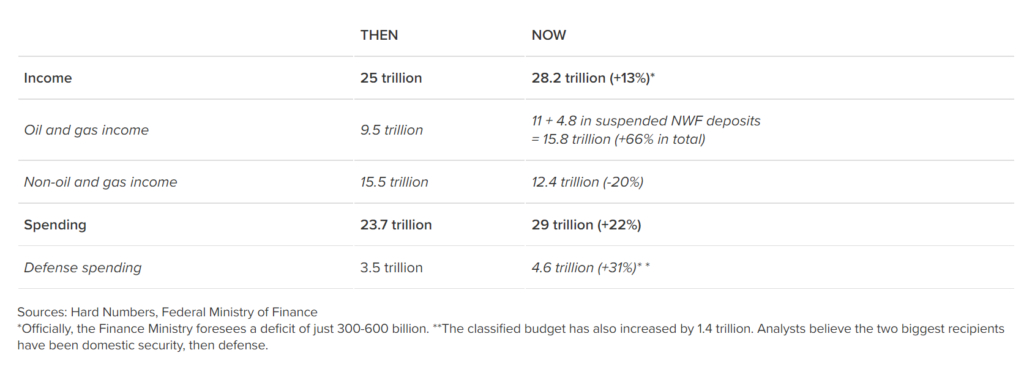

It is hard to imagine a more mixed policymaking picture than record export income combined with a twenty-percent decline in domestic economic activity. Watching the interactions between stakeholders in the federal budget process offers remarkable insights into their priorities and concerns related to short- and long-term income. This section will look at how income and spending have shifted this year before considering why President Vladimir Putin has just signed off on a change to the “Fiscal Rule,” which has dictated the volume of transactions to the National Welfare Fund (NWF) since 2017.

The ruble’s appreciation means that this year’s record export income has converted less favorably into rubles. This is a regular feature of Russian fiscal planning. A (more or less) free-floating exchange rate keeps the ruble value of export income more stable than it may seem from outside Russia. When oil prices are low, a weaker exchange rate can also ensure that export income doesn’t fall as sharply in ruble terms.

The main reason why oil and gas income has provided a remarkable lifeline is the government’s decision to suspend its own fiscal rule. This redirected into this year’s budget 4.8 trillion rubles ($79 billion) that would have been deposited into the NWF early next year. The comparison in Table 1 between the original 2022 budget (signed off in late 2021) and the current outlook for this year shows a 66-percent boost to oil and gas income. Even so, the collapse in non-oil and gas income due to the domestic economic downturn, combined with higher security and defense spending, means that the government will not avoid deficit spending this year.

It became clear that annual spending would overtake income much earlier in the war, during Q2, when classified spending started growing to fund the war effort as well as a domestic security crackdown. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov acknowledged Russia was heading for a deficit measuring 2 percent of GDP as early as June.10 There have since been pockets of “good” news in terms of income. Finance Ministry data suggest that income was still ahead of spending by 128.4 billion rubles ($2 billion) by the end of October. This was partly enabled by a special 416-billion-ruble ($6.9 billion) tax on the record profits made by Gazprom, which is 50 percent state-owned.11 And yet, a deficit is still being planned. Twenty percent or more of Russian annual expenditures accrue in December, a month in which economic activity and state income tend to slow down.

The government’s strategy for covering the deficit has kept changing. In late October, Prime Minister Aleksandr Mishustin confirmed that a deficit would be covered this year with funds from the NWF. Meanwhile, the Finance Ministry has gradually reintroduced borrowing on domestic markets. This started slowly in October but, on November 16, the ministry announced its largest-ever issuance of Federal Loan Obligations (OFZ), measuring about 0.5 percent of GDP.12 The new bonds have proven popular with Russian banks. These are demanding a rate of return seventy basis points above the 7.5-percent key interest rate for the shortest maturities, to account for inflation and uncertainty.

Resorting to domestic borrowing in addition to raiding the NWF isn’t simply the result of a growing deficit. The NWF is being pulled in several directions at once. We already know expected deposits from oil and gas income were suspended this year to fund day-to-day spending. Moreover, assets held in sanctions-wielding countries have been blocked and some of the fund’s sparser resources have already been committed to emergencies in the private sector, like the recapitalization of Aeroflot.13

Discussions around the NWF’s long-term fate are also revealing of all the challenges Russian policymakers face, from sanctions to the gloomy economic outlook.

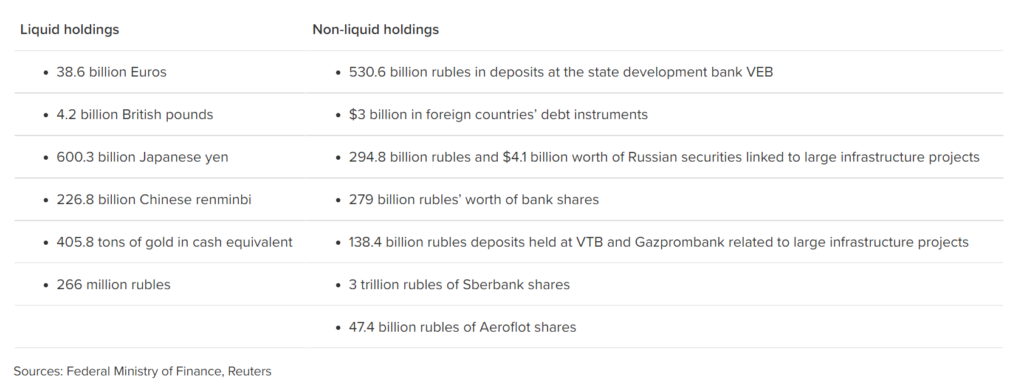

From a Russian perspective, the NWF is separate from the Central Bank reserves. In 2008, the original rainy-day fund set up in the early 2000s, the Stabilization Fund, was split into the NWF and a Reserve Fund, which was meant to manage oil and gas income. But the Reserve Fund was run down in the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea and the first batch of Western sanctions, both in 2014. From January 2018, a single NWF has accumulated excess oil and gas income, following a fiscal rule whereby income above a cutoff price per barrel of oil ($45 was planned for 2022) was deposited into the NWF for it to invest in foreign currency and other less liquid assets.

The Finance Ministry oversaw a de-dollarization strategy ahead of 2022, as can clearly be seen from the last publicly available distribution of NWF assets, published on February 1, in which US dollars do not feature in liquid holdings.14

Table 2: Russian National Welfare Fund holdings on 1 February 2022

Unfortunately for the Federal Ministry of Finance, the United States was not alone in blocking the NWF’s assets alongside the Central Bank’s reserves. Some of the NWF’s Western currency assets are held by the CBR on its behalf, and should therefore still be accessible. But this may not cover the entirety of the $112.7 billion in liquid holdings declared on February 1. The NWF’s vulnerability to Western sanctions has been an important factor in the discussion about what should happen to the fiscal rule from 2023 onward, after its temporary suspension this year to support day-to-day spending.

At the beginning of this unusual budget season—Siluanov and the head of the Duma Budget committee Andrei Makarov agreed it was “the most difficult ever”15—the Finance Ministry was arguing that the price cutoff should be raised to $60 to raise more immediate revenue. The CBR and the Audit Court—presided over by former Finance Minister Aleksei Kudrin, who will soon switch to running the holding company of Yandex—both objected to this policy.16 The two institutions also argued that the original budget was based on growth projections which, while gloomy, were still too optimistic. So why object to more immediate revenue for the federal budget? Probably because they believe conditions will worsen, and the NWF needs everything it can get now to plug deficits in the difficult years to come.

Moscow hasn’t quite reached the end of the budget season, but a compromise on the new fiscal rule has already been found, and President Putin has signed off on it.17 From January 1, 2023, there will be no official cutoff price. Instead, the government projects a base of oil and gas income of eight trillion rubles per year for 2023–2025, which it believes is possible if the Urals index stays between $60 and $75 and production stays between nine and ten million barrels per day. Income above the base is to be made available to the NWF, which will invest the money into “friendly currencies.”

The new rule comes with a lot of leeway: the amount to be kept for NWF deposits will be decided on a monthly basis. This isn’t only the result of anticipated budgetary issues; it is also very clear that the Ministry of Finance does not know whether it will be able to find friendly currencies without any risk of blocks or confiscation. Investing in renminbi on the magnitude needed by the NWF cannot happen without Beijing’s approval. It should be a goal of Western policy to dissuade China from helping Russia invest its energy income.

However, with the NWF on the hook to at least partly cover the deficits of the next three years and only meager fresh funding planned under the new fiscal rule, it is clear that the Ministry of Finance plans on running down nearly all the NWF’s accessible and liquid assets over the next three years.

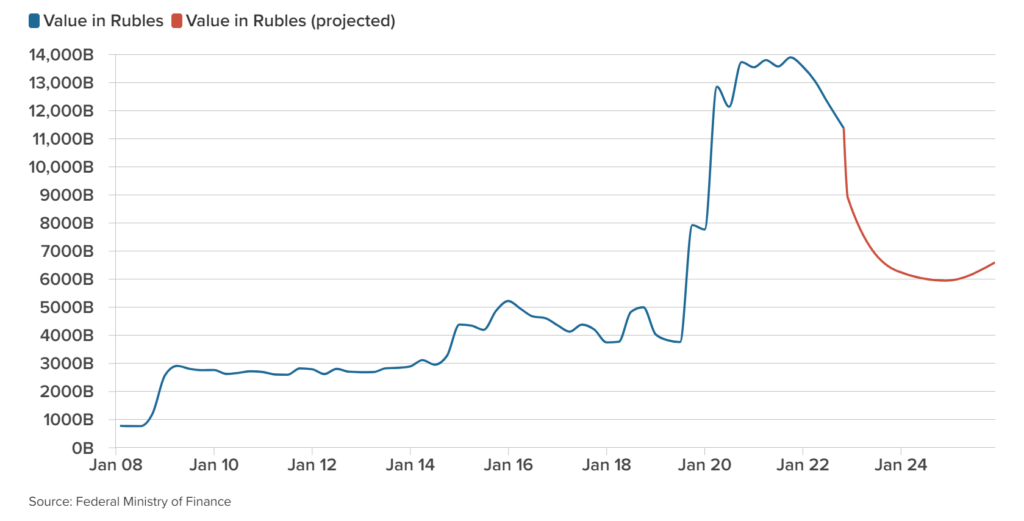

Figure 3: Russian National Welfare Fund

Looking at the federal budget in greater detail has shown that, even with this year’s purported windfall oil and gas income, the Ministry of Finance is struggling to keep up with current spending, let alone invest. But as the situation worsens, couldn’t the institution that has played a pivotal role in withstanding the initial shock ensure Russia continues to muddle through? What will the Central Bank do over the coming years?

III. Reserves and the CBR’s shrinking room for maneuver

Without the Central Bank’s drastic policies, Russia may have faced a financial crisis early in the war. The fact that the banking system withstood the shock to confidence—especially when the lender of last resort had just been deprived of more than half of its FX reserves—is no mean feat. However, the CBR is not all-powerful. This section will look at how the CBR has managed hard currency since the invasion before looking at its room to maneuver next year, when export income is expected to be considerably lower.

Where’s the money?

The oft-cited figure of $300 billion in “frozen” assets is derived from the last time the CBR made the composition of its FX reserves public, in January 2022. The report has since been removed from the CBR’s website, but can still be downloaded via the Wayback Machine.18 What the Group of Seven (G7) and a few more likeminded countries decided to do in the weekend after February 24 was, in fact, to block the CBR and NWF’s access to their holdings. The use of the word “freezing” is not accurate. It also suggests the sanctions-wielding capitals know exactly what assets they are freezing, when this is not the case.

The Atlantic Council’s private conversations with authorities in the United States and abroad suggest that the total of known, identified assets is less than one-third of the $300-billion figure, and intense work is being done in consultation to identify where the rest is, and which Russian institution owns what.

The CBR, predictably, is not making the job any easier. In addition to stopping its regular publication of FX composition, it has also cut off its regular reporting on FX reserve totals, so observers can now only see total reserves, including FX and gold. This indicator has been on a slight downward path since the beginning of the war, falling from $630 billion in February to $540 billion in October. Buried in a report on regional inflation, the bank argues that the dip in dollar value is because of the relatively low share of dollars in the overall mix.19 The dollar has appreciated against other currencies this year, so Russia’s total reserves have shrunk in dollar terms.

It is doubtful that this is the only factor at play. The CBR is still forcibly converting 50 percent of export income. It is clearly swapping this back to banks and firms that need FX. But with lower imports and no servicing of foreign debt, these liabilities are lower in practice than they were pre-invasion. The euros and dollars may well be accumulating off the Central Bank’s FX balance sheet—for instance, with the private banks that the European Union has refrained from sanctioning (Gazprombank, Credit Bank of Moscow, and Rosselkhozbank)—but, in this case, it should be a priority for Western policymakers to inject the maximum amount of uncertainty and complexity into these banks’ ability to move the money fast to serve CBR priorities. Sanctions policymakers also need to remain alert to unusual, large transactions to “nonaligned” central banks and sovereign wealth funds.

Less income, more stress

The CBR’s job is made easier when high commodity prices increase export income. Until 2008, the bank’s main role was to build up FX reserves and flood the market with rubles to prevent over-appreciation. Every time Russia has seen a sharp decline in its oil revenue (2008, 2014–2015, and 2020), the CBR has merely been able to smooth the transition to a lower exchange rate, not arrest it. Realizing a fixed-exchange-rate policy was unsustainable was the main reason the bank shifted to a policy of inflation targeting with independent rate setting in November 2014. But Russia’s dependence on goods imports means the bank still cares about the exchange rate, as it remains a key determinant of inflation.

With or without an effective G7-led oil price cap, the central scenario for 2023 is that Russia will sell lower volumes of oil and gas, at lower prices. The third-quarter data show this trend, yet the ruble hasn’t depreciated (see Figure 1). This does not mean that the special measures introduced at the beginning of the war—including capital controls—have succeeded where reserves and rates policies failed until 2014. The Central Bank will be forced to allow the ruble to depreciate before long, simply to ensure that the lower export income converts more favorably into rubles.

While it can be prudent in how it lifts capital controls, the CBR will struggle to smooth this transition to a weaker ruble. The two main tools at its disposal—reserves and interest rates—are blunter than they were before the invasion.

Before the war, the CBR could use its colossal reserves (the fourth largest ) to buy rubles, and thereby smooth depreciations. This was a reasonably effective tool, though no match for the effect oil price fluctuations had on the ruble exchange rate.

The two countervailing forces can be compared using a simple vector autoregression (VAR) model tracking the monthly interactions of the Urals price index, domestic production and prices, the ratio of Central Bank loans to FX reserves, nominal exchange rates, and interest rates between 2007 and 2021. On average, a 15-percent negative shock to oil prices causes the ruble to depreciate 5 percent against a basket of dollars and euros. The average CBR response through selling reserves arrests less than a third of this effect, and the depreciation tends to happen anyway after the policy’s effect wears off. This was before sanctions-wielding governments blocked the CBR’s access to reserves held within their institutions.

Unfettered access to these reserves also made the CBR an extremely credible lender of last resort for the domestic banking system. Nothing prevents the CBR from lending more rubles than it can access in foreign exchange but, in a high-inflation environment, it will want to avoid giving the impression it is just printing rubles. In the two decades before 2022, the bank never lent out more (at any given time; in rubles, euros, and dollars combined) then it had stored in FX reserves. It arguably broke this unwritten rule in February and March, when its lending reached 75 percent of pre-invasion FX reserves—above the amount to which it really had access following the sanctions. In 2023, domestic banks’ balance sheets will come under stress as they finally update their asset valuations after months of suspended animation.

Deputy Governor Alexei Zubotkin has acknowledged that the blocked reserves place additional pressure on the second instrument at the bank’s disposal: interest rates.20 Over the past decade, the bank has acquired a dominant role in dictating the cost of lending through its key interest rate, which was introduced in September 2013. February 2022 showed just how helpful this can be for keeping faith in the banking system. But interest rates have proven a much less effective instrument for smoothing depreciations over the years. The same VAR model shows interest rates becoming more effective in controlling inflation after the CBR switched to an inflation-targeting mandate in 2014, but no significant improvement in its ability to smooth depreciations.

The CBR can expect challenges to compound in the near future. It lacks sharp enough instruments to smooth the transition to a weaker ruble. Expansionary budgets tend to increase inflation expectations. The bank may also need to lend to struggling banks more than it has in accessible FX reserves, which will further fuel expectations. Like the National Welfare Fund, the CBR is also coming under pressure to fulfil ever more varied and esoteric duties, from issuing guidance on which licensed financial professions should be exempt from the military draft21 to cracking down on Telegram channels suspected of promoting “pump and dump” buying frenzies.22 Overall, we expect the CBR to face a much more challenging year in 2023.

Conclusion

Though largely enabled by one dominant factor – oil and gas export income – Russia’s response to sanctions and the exodus of Western firms has been competent.

In retrospect, it is easier to see how effective some planks of the “Fortress Russia” strategy have proven, at least in withstanding the initial shock of Western sanctions. A Central Bank with a clear mandate and an influential rates policy can concentrate on shoring up confidence in the domestic banking system. A “de-dollarized” National Welfare Fund provides an extra cushion when deficit spending becomes inevitable. And, as we might have expected, exporting crucial commodities at a time of heightened uncertainty will provide an income boost, however temporary.

But risks for Russia remain, largely on the downside.

As Atlantic Council Senior Fellow Carla Norloff writes in the Guardian,23 sanctions may have individual weaknesses, but they work through force multiplication. Export controls are beginning to bite. Despite the record income of Q2, sanctions and embargos have already cost Russia billions in revenue this year by lowering Western demand and putting Moscow in a difficult bargaining position with new buyers. Lower income will require a weaker ruble to sustain public spending. But the Central Bank is now deprived of the monetary policy tools which could have helped it ensure this transition was a smooth one.

The anticipation of lower income already means that the Russian government is planning on running down the liquid part of its National Welfare Fund. Western policymakers should remain vigilant to long-term investments being made in “friendly” denominations, like Renminbi. They should also continue to work on filling knowledge gaps, especially regarding which Russian assets Western central banks currently hold. Progress on this front is a precondition for any kind of negotiation on Russia’s withdrawal of Ukraine and its payment of reparations.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News