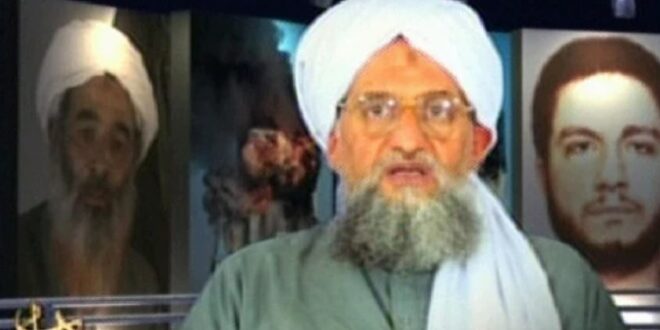

Following the July 31, 2022 killing of Al-Qaeda leader Ayman Al-Zawahiri, we are republishing two archival MEMRI JTTM reports by MEMRI senior analyst Dr. Nimrod Raphaeli. The first report, from 2005, focuses on information found on Al-Zawahiri’s computer after it was seized in an October 2001 raid on Al-Qaeda’s offices in Kabul, which concerned, inter alia, his clandestine activity in Afghanistan. The second report, from 2002, gives information on his background and his rise to prominence.

The Coded Messages of Ayman al-Zawahiri

Introduction

During the bombing campaign by the United States in Afghanistan in 2001, many of the leaders of Al-Qaeda escaped their stations in Kabul and in other cities, leaving behind a treasure trove of computers and documents. One of the computers left behind belonged to Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, Osama bin Laden’s second in command in Al-Qaeda and the primary source of its Islamist ideology. Al-Zawahiri’s PC was found in October 2001 in a building in Kabul that was used by Al-Qaeda as an office.[1] The London-based Saudi paper Al-Sharq Al-Awsat gained access to al-Zawahiri’s computer, which contained many of his messages to his collaborators about organizational and ideological matters. The newspaper had also obtained copies of correspondence with Al-Zawahiri from Islamist organizations in London as well as from former members of Islamic jihad.[2]

The recorded messages in the hard-drive and the correspondence between al-Zawahiri and members of the jihadist movement shed light not only on the mode of operation and management of Al-Qaeda and other terrorist organizations but also on al-Zawahiri’s own thinking and concerns as well as his interaction with former associates in Egypt who had opted to dispense with the culture of violence. The messages often employ poetic language reflecting al-Zawahiri’s intellectual, in addition to his organizational, abilities; further, they are often in code and signed by numerous al-Zawahiri’s pseudonyms. To decode them, the daily Asharq Alawsat sought the help of Islamist groups in London and elsewhere, and serialized the messages in seven installments, published in the second half of December 2002.[3]

The International Front for Fighting the Jews and the Crusaders

Al-Zawahiri’s coded messages covered many themes and reflected the evolution in his thinking that eventually led to his co-signing with Osama bin Laden, the leader of Al-Qaeda, a declaration regarding “The International Front for Fighting the Jews and the Crusaders” in February 1998. Particularly interesting was the correspondence from either shortly before or shortly after the bombing of the American embassies in Nairobi, Kenya and Kampala, Uganda, on August 7, 1998 which is the first tangible terrorist act of the International Front. [4]

The merging the Islamic Jihad movement with bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda was viewed by his supporters as conceding the jihad [holy war] against the government in Egypt in favor of a globalized jihad advocated by bin Laden. Many of al-Zawahiri’s supporters considered the move unwise because their organization, the Islamic Jihad, was now confronted by a great power [the United States] and because many of its leaders had little faith in what they perceived as bin Laden’s questionable record on promises. As a result, many of al-Zawahiri’s supporters have deserted him, and he was compelled to borrow money from bin Laden and from other donors to finance the basic activities of his movement as well as his basic needs.[5]

Al-Zawahiri’s Pseudonyms

During his correspondence with his followers he used the name of Dr. Abd al-Mu’iz. More often, his coded messages were signed by al-Ustadh Nur [ustadh is an honorific title used to address educated individual]. The name Nur was chosen by al-Zawahiri because of his admiration for Nur al-Din Zanki, the son of Sultan Imad al-Din Zanki who fought the Crusaders ferociously in 1146. Zanki’s brother was the famous Salah al-din al-Ayoubi [known in the West as Saladin] who defeated the Crusaders in Hittin (on the shores of the Lake of Galilee) and eventually occupied Egypt. To his relatives and close friends, al-Zawahiri signed as “Abu Muhammad” (the father of Muhammad)—the only son of al-Zawahiri who was eventually killed with his mother Izzat Nuwair during the air campaign by the U.S. in Afghanistan.

Al-Qaeda in Coded Messages

Reflecting the obvious security concerns of his senior partner, bin Laden, al-Zawahiri wrote in May 3, 2001, or four months before the 9/11 attacks, a message signed by Dr. Nur “President of the Administration Council” about which Council, if it indeed existed, there is no knowledge. The message which included many coded words was addressed to abu Muhammad al-Masri, suspected of being a leader of one of the key cells of al-Jihad al-Islami which reported directly to al-Zawahiri. There was a reference to Omar Brothers Company (the Taliban movement under Mullah Omar); the profitable commerce (jihad for the sake of Allah); the market (armed action); the village (Egypt); the school (Al-Qaeda); the suffering from monopolies by international corporations (the pursuit of the members of al-Jihad al-Islami by the U.S. and other nations following the bombing of the American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania) and the foreign investors (Americans and Jews) against whom the International Front for the Fighting of Jews and Crusaders was established. The message also referred to Al-Sa’aayida] which left the market (al-Jama’ah al-Islamaiyya [the Islamic Group], another Egyptian terrorist group which had abandoned the armed struggle in Egypt and eventually denounced terror; and Abdullah’s Contracting Company (Al-Qaeda, headed by bin Laden) The message also talks about Omar’s Brothers Company having opened the market for trade, meaning that it had provided training camps for the mujahideen [holly worriers] in all Islamic countries. It referred to “foreign investors,” meaning Americans that “it was necessary to strike them and kill them.”

The message refers to the results of the dialogue with “Abdullah Contracting Company,” (Al-Qaeda) and the merging of the two companies to create “Qa’idat al-Jihad”[the official name of Al-Qaeda] which is one way of avoiding what he termed as the bottleneck, meaning the limited scope of action for his movement, the Islamic Jihad, within the confines of Egypt. It refers to “shifting the trade activities”, meaning the armed action to multinational corporations and the joint profit, meaning the attack on international targets abroad, one of the objectives of Al-Qaeda. Al-Zawahiri urged his interlocutor for a quick response after 8:00 p.m., using the fax code of a neighboring country, meaning Pakistan, because of the difficulty of reaching Afghanistan. The response, al-Zawahiri instructed, should carry this notation on top:” for the attention of Mansoor” which was another of al-Zawahiri’s pseudonyms. Because of its significance, the English version of message is provided below almost in its entirety:

“Dear brothers. I hope you are well and may Allah bring us together…I yearn very much to see you…. Let me summarize our situation as we try to return to our previous principal activity [terrorism]. The most important step was the opening of the school [Al-Qaeda] whose doors were opened before the professors [mujahideen] for a profitable trade [jihad for the sake of Allah]…As you know, the situation down in the “village” [Egypt] has become bad for the merchants and Allah has opened before us the door of mercy by establishing Omar Brothers Company [bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda] which opened the market for trade [training camps], and provided them the opportunity to rearrange their papers. May Allah reward them with his generosity. The benefits of trade here is bringing together the merchants [mujahideen] under one roof thereby contributing to their familiarity [with each other] and to cooperation, and particularly between us and Abdullah Contracting Company [another pseudonym for Al-Qaeda]. The result of this effort was the merging of the two companies [Islamic Jihad and bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda] and the ability to confront the foreign investors…to unify trade [jihad] in our entire region. Our colleagues see an excellent opportunity to advance the sales [jihad] in general and in the village [Egypt], in particular. They are determined to make this enterprise successful and hope to see it as a means of emerging from the neck of the bottle which suffocated us and shifting the trade to multi-national corporations, and joint profit. We are negotiating the details and both sides are optimistic. …We welcome those who wish to take part in our training programs but due to limited resources we ask that [the participants] share the cost of travel and consider it as a debt to be [repaid] when we are better off…. I reiterate our welcome of any idea that would bring back to the market, particularly the local market, [the ability] to compete with foreign investors.

“(signed) Chairman of the Board of Directors Dr. Nur”

Al-Zawahiri’s many appeals to his former group to disassociate itself from the decision to disengage from violence and terrorism in this regard appeared to have fallen on deaf ears. There is no record in the confiscated computer of any response to al-Zawahiri’s various appeals.

The Renunciation of Violence in the Eyes of Al-Zawahiri

Al-Gama’ah al-Islamiyya was an Egyptian terrorist organization which had been involved in, among other things, the assassination of President Anwar al-Sadat. An issue that occupied much of al-Zawahiri’s attention and often drew his wrath was the decision by the movement in 1997 to suspend all violence both inside and outside Egypt. Perhaps even more disturbing to al-Zawahiri was the decision by the Islamic Jihad, the group which he had created and led before escaping from Egypt, to join al-Gama’ah’s renunciation of violence. His messages pleaded with both the leaders of al-Gama’ah and members of the Islamic Jihad to renounce that decision and to continue the course of jihad as embodied by the fatwa (religious edict) issued by Osama bin Laden, upon the establishment of the International Front to Fight the Jews and Crusaders.

One of the significant documents found in al-Zawahiri’s computer was a letter, dated October 4, 1998 – that was about two months after the bombings of the American embassies in Kenya and Uganda in which 224 people were killed, among them 11 Americans. For the first time, al-Zawahiri used his own name, rather than one of his several pseudonyms, to sign the letter. The open letter was directed to the traditional leaders of al-Gama’ah al-Islamiyya and decried what he saw as a setback in the Jihadist Movement due to the historical initiative of these leaders to renounce violence which they have taken while detained in Egyptian prisons.

There were secret messages between al-Zawahiri and abu Yasser (Rifa’i Ahmad Taha) the person in charge of military operations of al-Gama’ah al-Islamiyya which announced its responsibility for the terrorist act in Luxur, Egypt, in November 1997 which resulted in the death of 58 foreign tourists. The act was carried out by the Egyptian Islamist known as abu hamza (real name, Mustapha Hamza) who was accused by the Egyptian authorities of planning the assassination of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak while he was on a state visit to Ethiopia in 1995. Abu Hamza became the military commander of al-Gama’ah upon the extradition of Rifa’i Ahmad Taha by Syria to Egypt in early 2002.

According to Asharq al-Awsat’s sources, Egypt considers Rifa’i Ahmad Taha (47 years old), to be one of the most dangerous terrorists. He used forged Egyptian and Sudanese passports to travel between Iran, Afghanistan, Khartoum (Sudan) and Damascus prior to his extradition, and, according to Egyptian records, used multiple aliases such as Abdul Hadi Ahmad Abdul Wahab, Issam Muhammad ‘Ali Abdullah, and Salah ‘Ali Kamal.[6]

In a series of three messages, Al-Zawahiri continued to urge the leaders of the Islamic Jihad to refrain from pursuing a peaceful course. Resorting to a threatening language, al-Zawahiri warned his correspondent abu Yasser that the leaders who signed the cessation of violence statement would face a future like that of the head of the Muslim Brotherhood Hassan al-Banna, who was murdered in the middle of the night in February 12, 1949 “as a gift to King Farouk on his birthday.” An Egyptian Islamist who lives in London has interpreted the language as a warning to the leaders of the al-Gama’ah that they faced the same fate of al-Banna who made peace with the Egyptian government and made his famous declaration about his organization: “Neither brothers nor Muslims.” Al-Zawahiri’s messages advocated the continuation of violence as long as the Egyptian government “does not apply the shari’a” or [Islamic law] to govern the country. [7]

In the letter, al-Zawahiri wrote:

The Jihadist Movement in our times is still newly born and its actual age is short, although it has succeeded in wresting away- and keeping- a place for itself within the warring forces in the world. But the road in front of it is still long, since its enemies have had control over the nation’s resources for a long time and amassed armies that pursue it.

In a language full of bravado, al-Zawahri asserts in his letter that “The Jihad Movement is hard to uproot, tame, subdue or force to make concessions on its principles despite the merciless violence that it faces…” He referred to the ‘blessed results’ of the successful destruction of the two American embassies due to the unity, cooperation and harmony [among the various segments of the Movement]…”

Using a preacher’s style in addressing the leaders of al-Gama’ah all-Islamiyya he said that “presently America and Israel consider the Jihadist Movement their first real danger in the region because of its potent opposition to them.” He then talked about what he considered as the tragic aspect of the Movement and said that “no other political movement in Egypt could survive what this organization [al-Gama’ah] has endured”. He claimed that there were 60,000 al-Gama’ah’s prisoners in Egypt and that the military tribunals had sentenced hundreds to death or long-term incarceration. Not known for modesty in his statements, al-Zawhiri referred to “assassinations in the streets [of cities] and rural areas,” in addition to “raids and unbridled torture and harassment “All this, in his opinion, signified that the Movement and its message had supporters, followers and sympathizers unlike any other group. He added: ‘The Jihadist Movement did not gain this support in a vacuum, but for two reasons: First, the lucidity of its opposition to domestic and foreign heretic powers… exposing the strong nexus between them. Second, the Jihadist Movement paid a high price for its positions with its sons’ blood and sacrifices.’

Al-Zawahiri expressed surprise at what he called “the initiative to end violence” that was issued by the leaders of the movement from inside Egyptian jails and said: ‘I consider [this initiative] a losing proposition from the outset because it is not how the Jihadist Movement achieved historical accomplishments that made it proud, and turned it into a symbol of perseverance, sacrifice and munificence.” Al-Zawahiri discussed what, in his view, were the negative aspects of the initiative to stop violence and said that this initiative “exposed the differences within al-Gama’ah al-Islamiyya” as well as the problem of leadership within it. He wrote: “It is enough that it portrayed the Jihadist Movement as weak, because the political interpretation of this initiative is capitulation, since in any battle the one who surrenders is forced to stop the fighting and incitement, to accept captivity and to surrender his people and weapons without any reward… [The initiative] showed that there are separate groups within the Jihadist Movement ready to reach an understanding with the government, which allows the government to manipulate each group separately.”

Al-Zawahiri then discussed “the embarrassing problems and questions” that the radical movement faces: “If we stop [the violence] now,” he wrote, “why did we ever start? Why do the jailed brothers issue statements without consulting with their brothers on the outside?” Al-Zawahiri maintained that the statement to renounce violence “shook the image of the jailed leaders in the eyes the youth and shocked them severely, which is a grave loss to the jihadist movement as a whole.” He addressed the jailed leaders saying: “You, our beloved … represent something that is greater than yourselves. You are, by the grace of Allah, symbols of the Jihad Movement at the heart of the Islamic world… you clashed with the most prominent American criminals by dragging them into an open battle with the masses of the nation and without giving up the struggle with the Egyptian government.” He inquired whether the suspension of violence includes “secret terms” with the Egyptian intelligence services which are unknown to the leaders of the jihadist movements abroad. He wanted to know whether the suspension of violence would put an end only to operations against Americans and Jews inside Egypt to avoid confrontation with the Egyptian regime. Or, he asked, would it apply to Americans and Jews outside Egypt? He asserted that the decision had shaken the picture of the imprisoned leaders like Omar Abdul Rahman, the spiritual blind leader of al-Gama’ah al-Islamiyya who was sentenced to prison for life in the United States for his involvement in the first terrorist act in the Twin Trade Towers in New York in 1993. He characterized the initiative as “an enormous loss to the jihad movement as a whole.”

Unlike subsequent letters, this letter did not contain coded terms or [secret] nicknames… and it seems that al-Zawahiri intended it for the rank and file of al-Gama’ah al-Islamiyya and he therefore signed it with his own name.”

Attacks on Al-Zayyat

Muntasir al-Zayat served for a long time as the lawyer for the Islamist organizations in Egypt. However, in 1997 he adopted the decision by the Islamist terrorist organizations in Egypt which called for cessation of violence. Al-Zayat published a book, Al-Zawahiri as I Knew Him, which was serialized in the London-based daily Al-Hayat from 10-17 January, 2002. While the book was generally polemical two significant points have emerged (a) al-Zawahiri has failed in most of his undertakings; and (b) any further violence against the government of Egypt can neither be sustained nor justified. Al-Zayat had already articulated his views in an interview with Asharq al-Awsat on April 9, 1999.

From al-Zawahiri’s perspective, “the International Front to Fight the Jews and the Crusaders is the right step in the right direction, and we were eager, and still are, to include al-Gama’ah in it, as a way to strengthen the thorn of the Mujahideen and to spite their enemies”[8] Pained by the position taken by al-Zayyat, Al-Zawahri wrote in a coded letter to one of the leaders of the Gama’ah, Issam Mutair whom he addressed as “Abu Yasser,” who is no other than Rifa’i Ahmad Taha, referred to earlier. The following is excerpts from the letter:

My Noble Brother. I hesitated writing to you after it was broadcasted that you have announced the cessation of all military operations…I have spoken with you about the subject and have written to you more than once but have received no response to what I have written. It occurred to me that writing to you again may be considered by some brothers as interfering in what is of no concern of mine and [sticking] my nose in the affairs of others.

After the initial reluctance to interfere in someone else’s business, al-Zawahri asked for “clarifications” on the following matters:

“First, I wish to ask you whether what was published has really been done. If it has, what are the details? This raises frightening questions: for example, has there been an agreement between all of you on the subject? And what is the policy towards the government that you have agreed upon?

[Second], If an agreement between yourselves and the government has been concluded what are the details of this agreement? Why it was not announced? Was it a secret agreement fully or in part? And could this secret be known to the government but hidden from us? If such agreement was reached, what would the government allow you to do under the agreement?”Al-Zawahiri refers to activities by former members of al-Gama’ah and asked whether it was true that some of them are organizing themselves into a political party. After decrying the many statements issued by members of the al-Gama’ah from prison al-Zawahiri considered these actions as “a dangerous retrogression” from the principles of al-Gama’ah and “a clear contradiction” from the movement’s “position and legacy.” The letter is signed by “Your loving brother, Abd Al-Mu’iz) and dated April 19, 1999.

Islamists in London have recently confirmed to Asharq al-Awsat that Rifa’i Taha who had been sentenced to death in absentia by an Egyptian military court in Alexandria has not been executed after he was extradited by Syria in early 2002. However, he has refused a deal offered to him by the Egyptian Government to renounce his earlier writings that would have permitted the assassination of members of police and other security agencies. So far, Taha has refused the deal and remained in prison. [9]

Justification for Blowing up the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad

The Egyptian embassy in Islamabad (Pakistan) was bombed by al-Zawahiri’s movement, al-jihad al-Islami, in 1995. Asharq al-Awsat obtained a small booklet from the Jihad movement in London which provides the political and religious principles that guided the Islamic Jihad in their decision to blow up the Egyptian Embassy. The booklet, authored by al-Zawahri and distributed sparingly among his supporters in Pakistan and Afghanistan, explored the reasons for blowing up the embassy which he considered as a martyrdom operation.

The booklet, No.11 is one in a series of publications by al-Mujahideen. It dealt with the suicide and martyrdom operations from the viewpoint of Islamic law (al-shari’a). Al-Zawahiri revealed that two members of his movement, representing “a generation of mujahideen who decided to sacrifice themselves and their fortune for the sake of Allah because “the path to death and martyrdom is a weapon not possessed by the despots and their collaborators who worship their salaries without [the benefit of] Allah.” [10]

Al-Zawahri said that the “martyrdom” operation by the Jihad group against the Egyptian embassy has succeeded to destroy a number of beliefs and values, including the Islamic notion of “the subordinate of the worshipped,” which means that subordinates are not responsible as long as their crimes “were [acts] of obedience to their masters.”

Al-Zawahiri sought moral and religious justifications for the killing of Egyptians at the embassy by declaring that these innocent individuals are employees, diplomats and guards and they are all supporters of the Egyptian government. He alleges that the Egyptian government has prevented the Islamic shari’a from being adopted by Egypt and, instead, it imposed a secular constitution and opened the gates of prisons to thousands of Islamists and hanged hundred of them. While al-Zawahiri mounted vicious attacks on all branches of the Egyptian government as well as on the religious establishment whose clerics he labeled as “the clerics of evil” his most venomous attacks were directed against the foreign ministry because, in his mind, that ministry implemented the government policy of supporting overseas governments that are hostile to Islam and because it pursued the Mujahideen abroad and participated in “the conspiracies of their kidnapping.” As a case in point, he refereed to Tal’at Fuad Qassim (a.k.a. abu-Talal Al-Qassimi, the official spokesman of the al-Gamaa’ah al-Islamiyya who was allegedly kidnapped in Croatia.[11]

The Execution of Young Boys for Spying

Al-Zawahiri claimed that his movement, the Islamic Jihad, had discovered more than one case in which members of the Egyptian intelligence services (mukhabarat) have practiced homosexuality with their agents and informers as a form of blackmail. One of these informers was the son of one of the leaders of al-Jihad movement during the time bin Laden and Al-Zawahiri resided in Khartoum, Sudan, in 1992-1996. When the spying and homosexual activities of the boy were discovered, allegedly due to a tip from the Sudanese secret police, a Shari’a (Islamic law) court summoned by al-Zawahiri condemned the boy to death. It was rumored that the boy was executed by al-Zawahiri himself. Following his trial and before his execution, the boy had purportedly revealed the extent of the information he supplied to the Egyptian intelligence which, in turn, it shared with the Sudanese government. Sudan accused al-Zawahiri of maintaining “a state within a state” and forced him and bin Laden to leave the country. Another boy was also caught spying for the Egyptian intelligence but, under pressure from the Sudanese government, he was set free.

Investigations about Misallocation or Waste of Money

Another set of documents discovered in Al-Zawahiri’s computer dealt with committees which investigated members of the movement about intra-group conflicts and the misallocation or misuse of the movement’s resources. One document in particular dealt with the bank account of an Islamist leader in London by the name of Abbas who is believed to be ‘Adel Abdul Majid Abdul Bari who is in a British jail with two accomplices, the former Egyptian army officer Ibrahim Hussein ‘Idroos and the Saudi Khalid Al-Fawaz pending, at that time, extradition request from the United States in connection with the bombing of the two American embassies in East Africa in August 1998. The document accused members of the Jihad in London for wasting money by buying desks and new computers to be used for the issuance of an Arab weekly in London.

A document revealed a message sent by an Islamist leader by the name of Abu Al-Hassan to ustadh Noor [al-Zawahiri]. Abu al-Hassan, serving as a shari’a judge believed to have lived in Afghanistan until the fall of the Taliban regime, apprised al-Zawahiri in a coded message of the difficulties of investigating the case for several reasons. These difficulties included reaching the parties who reside in different countries, the absence of some parties from their stations and the foot dragging of others in answering questions and the absence of a suitable [safe] phone line.

Spying on Members

Another document revealed the existence of special security cells whose responsibility was to pursue those whose loyalty to the secret organization was in doubt. One of the cells was able to discover a number of individuals who collaborated with various Arab intelligence services, including one individual by the name of Abu Ibrahim al-Masri. (he is believed to be Ahmad Sabri Nassrallah) who maintained contacts with the Egyptian intelligence as well as with the political intelligence of Yemen. One document in al-Zawahiri’s computer is a video covering the investigation of al-Masri by elements of the al-Jihad and his “quick confession” regarding his penetration into Islamist movements, including Al-Qaeda and his sending valuable information about the Islamist movements in Yemen, Afghanistan and Pakistan, perhaps to the Egyptian Mukhabarat. Al-Masri was said to have been “disciplined” and released while his activities were revealed to Islamist movements to avoid any dealings with him.[12] One assumes that if al-Masri was passing information to a Western intelligence service he would have most likely been executed.

“Knights under the Banner of the Prophet”: Al-Zawahiri’s “Last Testament”

Shortly before the coded messages were discovered, al-Zawahiri smuggled out of Afghanistan a book titled “Knights under the Banner of the Prophet,”[13] In the introduction to the book al-Zawahiri wrote: “I have written this book in fidelity to our generation and the generations that will follow, for I may not be able to write any more in the midst of these disturbing circumstances, and I expect no publisher to publish it and no distributor to distribute it.”

The book uses two sub-titles, “Reflections into the Jihad Movement,” and “Reflections under the Roof of the World,” His “knights” are used as an allegory for the leaders of the jihad movement. The London daily Asharq al-Awsat suggests that the title of the book may have been a reaction to the “Knights of the Holy Grail” – a term commonly used to the Crusader knights in the Middle East in the middle ages.[14]

In his introduction al-Zawahiri wrote: “This book was written in an attempt to bring to life the awareness of the Muslim nation about its role and obligation…and the extent of the enmity towards it by the new Crusaders so that it would be able to separate between its enemies and its guardians.” He bemoaned the penetration of the jihadist movement by a number of “brilliant names” added by our enemies to serve as “authors of falsehoods, traders of principles and sellers of fatwas.” Al-Zawahiri climbed quickly from his despair by taking pride in the events of 9/11 and warned “the forces of evil” that “our nation is nearing your defeat, day after day…and your battle is doomed to fail. All your attempts may delay the [Islamic] nation’s victory but not to prevent it.”

Al-Zawahiri discussed in the book his experience in Afghanistan where “my age has increased by a hundred years.” Afghanistan provided a safe base of operations after years of being in prison or in the run in Egypt. The jihadist movement needed a jihadist stage that would “serve as an incubator where the seed will grow and where it can gain its operational, fighting, political and organizational experience.”[15]

After discussing the murder of Sadat, the attempts on the lives of President Husni Mubarak and the former Egyptian prime minister ‘Aziz Sidqi al-Zawahiri concluded with the last chapter which he titled: “Carrying of the battle to the land of the enemy is the principal objective of the Islamist movement.” Al-Zawahiri described “the suicide operations as the most effective method to spite the adversary and the least [disadvantageous] in terms of losses to the Islamists.” He added: “It is necessary to choose the targets and the type of weapon that will impact the hinges of the enemy’s structure and to deter him sufficiently to cease his tyranny.”

The struggle of the Islamist movement, according to al-Zawahiri, is for the creation of an Islamic state in the heart of the Arab nation. But since the “the Crusaders’ Alliance” will not allow this to happen the struggle can no longer be regional but be global. According to al-Zawahiri, the “crusaders’ alliance” has mobilized many instruments to wage war on Islam:

(1) The United Nations

(2) The client governors of the Muslim peoples

(3) Multinational corporations

(4) International communications and information systems

(5) World news agencies and satellite TV stations

(6) International aid agencies which are used as a façade for espionage, proselytizing, organizing coups d’etat and transferring weapons

This list is significant because it could suggest that entities that fall into any one of the six categories could be singled out for attack.

Against this alliance, al-Zawahiri insisted, stand the fundamentalist alliance of Jihadist movements in the different lands of Islam and the two states that were liberated in the name of “jihad for the sake of Allah”, namely Afghanistan and Chechniya. While this alliance is still in its infancy “it is growing, accelerating and multiplying rapidly.”

He pledged to carry the battle to the enemy, particularly the three largest enemies, America, Russia and Israel so that they will not be left in peace while they direct the battle between the Jihadist movements and our governments. What is striking in this statement is the inclusion of Russia, and for the first time, to the list of the declared enemies which for most of the book was limited to the Jews and the crusaders. [16] In an interview, al-Zawahri explained his vision about the war against America:

Our weapon in this battle is patience (sabr), perseverance (musaabara) and reliance upon allah (tawakkul) in our fight against America. By the permission of Allah, this war will continue until the bleeding of America will result in its collapse. If America possesses advanced weapons of mass destruction and well-equipped armies, then it should know that we possess, what they cannot [sic]. The love of death is the path of Allah.[17]

The Renouncing of Violence by Islamist Groups in Egypt

The renouncing of violence and terrorism by the Islamist groups in Egypt was confirmed a number of books. One of these books, titled The Strategy and Bombings by Al-Qaeda.” It was published in 2003 and serialized in Asharq al-Awsat in four installments between January 11 and 16 of that year.[18] The book condemns Al-Qaeda and its activities in the most severe and critical language. The authors of the book, some of whom are still in Egyptian prisons, argue that Al-Qaeda was born “in the jihadist Afghani womb” which follows that its objectives are Afghani objectives in the first place. This is the reason for the strong alliance between Al-Qaeda and the Taliban movement which controlled ninety percent of the Afghani territory. The authors accuse Al-Qaeda for forcing the Islamic nation into a conflict it cannot win and has no desire in it.” As a result of a wrong strategy the following negative events have ensued:

The collapse of the Islamic state in Afghanistan

The pursuit of Al-Qaeda and the Islamist movements in the context of global security

The interests of the Islamic minorities in Western countries have been harmed

Israel was able to achieve its objectivesConclusion

Al-Zawahiri emerges from these messages as a man whose leadership of the Islamic Jihad in Egypt was in disarray. His pleas for the continuation of violence in Egypt had fallen on deaf ears. His brand of terrorism is no longer local; it is globalized.

There is also an irony in his situation. A man who for his entire adult life has engulfed himself in secrecy now faces the unpleasant reality that his coded messages were sold in the bazaar of Kabul to no other than the reporter of the Wall Street Journal, the epitome of American capitalist culture which he so deeply despises.

The most telling lesson one learns from Al-Zawahiri’s messages is his undiminished commitment to terrorism regardless of the circumstance but that he is a lonely figure with very few confidants which makes the task of tracing and capturing him all the more difficult.

Ayman Muhammad Rabi’ Al-Zawahiri Biography and Background

The following report, with the title, “Ayman Muhammad Rabi’ Al-Zawahiri: The Making of an Arch Terrorist,” appeared in the Winter 2002 edition of the journal Terrorism and Political Violence (Vol. 14 No. 4, pp. 1-22).

Preface

Few individuals have had a more central role in articulating and practicing terrorism than Ayman Al-Zawahiri.[19] Though born into the Egyptian aristocracy and trained as a surgeon, this gifted individual has always been attracted to the most extreme forms of Islam. In 1998 he brought his Egyptian Islamic Jihad organization into a union with the forces of Osama bin Laden, known as Al-Qaeda (the base), in the effort to create a globalized network of terror whose capacities were demonstrated on September 11, 2001, as well as in the earlier destruction of the American Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania and in the damage inflicted on the USS Cole in the Gulf of Aden.

Introduction

Dr. Ayman Al-Zawahiri, a surgeon by profession, is the head of the Egyptian “Islamic Jihad” and second in command of the Al-Qaeda organization. He is the intellectual and ideological force behind it and its leader, Osama bin Laden. Azzam Tamimi, director of the Institute of Islamic Political Thoughtin London, says Al-Zawahiri “is their ideologue.His ideas negate the existence of common ground with other Islamist groups.”[20]

Following the air attacks by the United States on the Al-Qaeda bases in Afghanistan, and fearing that he might be killed, Al-Zawahiri was able to smuggle to England a short manuscript detailing the evolution and the travails of the Islamic Jihad and his association with the Islamist movements in Egypt and, ultimately, with bin Laden. The book, titled “Knights Under the Banner of the Prophet,” with the subtitle “Reflections into the Jihad Movement,” was serialized in the London-based, Saudi newspaper Al-Sharq Al-Awsat between December 2-12, 2001.[21] In addition, “a combination of happenstance and the opportunism of war” allowed a reporter of the Wall Street Journal to acquire for $1100 in Kabul Al-Qaeda computers left behind following the escape of their operators. The reporter was able to download hundreds of files regarding the organization, particularly concerning Al-Zawahiri’s internal correspondence and mode of operation.[22]

Al- Zawahiri – An Extremist Sui Generis

The Formative Years

Most rank-and-file members of the terrorist movement in Egypt, the Islamic Jihad, come from a peasant stock or from the slums of the Egypt’s large cities, mired in poverty and driven by despair. Ayman Al-Zawahiri does not fall into a typical category of Egyptian extremists– socially, economically or intellectually.[23] He comes from a distinguished family that seems never to have faced social or economic hardships; many of its members would be considered part of the elite in any society.

Al-Zawahiri’s family has its roots in the Harbi tribe from Zawahir, a small town in Saudi Arabia, located in the “Badr” area where the first battle between Prophet Muhammad and the infidels was fought and won by the Prophet.[24] Ayman Al-Zawahiri’s great grandfather, Sheikh Ibrahim Al-Zawahiri came to Egypt in the 1860s and settled in the city of Tanta in the Nile Delta where a mosque still bears his name. His grandfather, Sheikh Al-Ahmadi Al-Zawahiri was the Imam of Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo. His father, Muhammad Rabi’ Al-Zawahiri was a professor of pharmacology at Ein Shams University who passed away in 1995. His maternal grandfather, Abd Al-Wahab Azzam, was a professor of oriental literature and president of Cairo University as well as the Egyptian ambassador to Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, and was so known for his piety that he was referred to as “the devout ambassador.” His grandfather’s brother, Abd Al-Rahman Azzam [pasha], became the first Secretary General of the Arab League.

Ayman Al-Zawahiri was born on 1 June 1951, in Cairo’s Al-Ma’adi neighborhood. After graduating in 1968 from the Al Ma’adi secondary school he enrolled in the medical college of Cairo University and graduated, cum laude, in 1974, with an MD degree. He received a master’s degree in surgery in 1978 and was married in 1979 to Izzat Ahmad Nuwair who had graduated from Cairo University with a degree in philosophy but who met the criteria of “a devout wife.” Al-Zawahiri’s wife bore him one daughter in Cairo and at least three other daughters and a son elsewhere, but no information on his children is available.[25] He has two brothers — Hassan, who studied engineering and lives outside Egypt, and Muhammad, who followed Ayman’s path to Jihad and is reported to have vanished in Afghanistan.[26]

Becoming Islamist

At a young age, Al-Zawahiri began reading Islamist literature by such authors as Sayyid Qutb, abu Alaa Al Mawdudi and Hassan Al Nadwya. Sayyid Qutb was one of the spiritual leaders of Islamic religious groups, especially the violent Jihad groups. While other Islamists at the time, particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, were looking to change their societies from within, Qutb was an influence on Zawahiri and others like him, “to launch something wider.”[27] But like most Islamists before him and after, Qutb’s world views, defined in his book “Ma’alim ‘Ala Al-Tariq (Signposts on the Road), published in 1957, was predicated on a perfect dichotomy between believers and infidels, between Shari’a (Islamic law) and the law of the infidels, between tradition and decadence and between violent change and sham legitimacy. To quote Qutb himself, “In the world there is only one party, the party of Allah; all of the others are parties of Satan and rebellion. Those who believe fight in the cause of Allah, and those who disbelieve fight in the cause of rebellion.” In his book, Al-Zawahiri asserts that the Jihad movement had begun its march against the government in the mid-1960s when the Nasserite regime imprisoned 17,000 members of the Muslim Brotherhood and hanged Sayyed Qutb, the leading thinker of the movement at the time.

At the age of 15, Zawahiri joined “Jam’iyat Ansar al-Sunnah Al-Muhammadiyya,” (The Association of the Followers of Muhammad’s Path);[28] a “Salafi” (Islamic fundamentalist) movement led by Sheikh Mustafa Al-Fiqqi, but soon left it to join the Jihad movement. By the age of 16, he was an active member of a Jihad cell headed by Sa’id Tantawi. Tantawi trained Al-Zawahiri to assemble explosives and to use guns. In 1974, the group split because the group declared Tantawi’s brother as kafir (infidel) because he fought under the banner of kuffar or infidels which characterized the Egyptian army. In 1975, after the split, Tantawi went to Germany (and is said to have disappeared) and Ayman took over the leadership of the cell. He immediately organized a military wing under Issam Al-Qamari, an active officer in the Egyptian army at the time (Al-Qamari became Al-Zawahiri’s closest friend and ally. In his book, Al-Zawahiri as I Knew Him, lawyer Muntasir Al-Zayyat maintains that under torture of the Egyptian police, following his arrest in connection with the murder of President Sadat, Al-Zawahiri revealed the hiding place of Al-Qamari which led to his arrest and eventual execution). Al-Zawahiri’s extreme caution and secretive nature spared him the attention of police. To aid their secrecy the group avoided growing beards like most Islamists, and hence they were known as “the shaven beards.”

The Radicalization of Al-Zawahiri

The defeat of Egypt in the Six-Day War of 1967 has further radicalized Al-Zawahiri and his generation. As he points out in his memoirs: “The most important event that influenced the Jihad movement in Egypt was the “Naksa” (or “the Setback”) of 1967. The idol, Gamal Abd Al-Nasser, fell. His followers tried to portray him to the people as if he was the eternal leader who could never be defeated. The tyrant leader who used to threaten and pledge in his speeches to wipe out his enemies turned into a winded man chasing a peaceful solution to save at least a little face.”

Abd Al-Nasser was consumed by termites and he fell on his face amid the panic of his followers. The Jihad movement got stronger, realizing that the enemy was nothing but an idol created by the propaganda machine and the tyrannical campaigns against innocent people. The Nasserist movement was knocked out when Gamal Abd Al-Nasser died three years after “the Setback” and after the destruction of the legend about the Arab nationalist leader who will throw Israel into the sea.

Abd Al-Nasser’s crowded funeral was nothing but evidence of the coma that the Egyptian people were living through. It was the farewell for a leader that the Egyptians soon replaced with a new leader who took them to another direction and started to sell them a new illusion.[29]

At the age of 24, Al-Zawahiri’s intellectual development was greatly enhanced by Dr. Abdallah Azzam, a Palestinian, who came to Egypt to study at Al-Azhar University. His studies at Al-Azhar convinced Azzam of the role of Islamic Jihad as the solution to social and political problems. Azzam would become the spiritual leader of the movement of Arab and Muslim volunteers to the Jihad in Afghanistan, and the spiritual father of Osama bin Laden. (Azzam was blown up with his two sons in their car in Peshawar, Pakistan, in 1989, and their murder has remained unsolved).[30]

Al-Zawahiri’s advancement in the Jihad movement was relatively rapid. In a recent book by Muhammad Salah on The Afghani Arab Journey to Jihad, the author considers Al-Zawahiri as a distinctive phenomenon. Not only was Zawahiri’s background different from most radical Islamists but also his rapid rise to the top and his “heavy-weight impact on the thoughts of the various Islamic movements, in general, and on the Jihad Movement, in particular, was phenomenal.”[31] Indeed, by the early 1970s, barely 20 years old, Al-Zawahiri had obtained the rank of “amir” (or leader of a group or front) when he was implicated in the murder of President Anwar al-Sadat.[32]

Sadat’s Legacy and the Rise of Religious Extremism

When Anwar Al-Sadat had become President of Egypt upon the death of Gamal Abd Al-Nasser in September 1970, he envisioned Egypt as “The State of Science and Faith.” After years of suppression by Nasser, Muslim organizations, in general, and the Muslim Brotherhood, in particular, were permitted, indeed encouraged, by Sadat to operate openly. In the words of Al-Zawahiri, “Sadat let the genie [the Jihad movement] out of the bottle.” This was also “a time of political change from the Russian era to the American era” in the political life of Egypt.[33]

Sadat himself was either a former member or sympathizer of the Muslim Brotherhood, and he had a soft spot for them. In fact, during the Sadat reign, Egypt underwent a process of clericalization, as measured by the number of hours devoted to religious programs in the official Egyptian media, particularly Egyptian television. In 1963, religious programming on television did not exceed 2.3% of televised time but it rapidly increased to 8.97% in 1973 and to 9.54% in 1980. In terms of programming hours, televised religious programs increased from 528 hours in 1973 to 754 hours in 1980/81 or to an average of about two hours a day. On Sadat’s orders, the five daily Muslim prayers were televised live.[34]

By the time the leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood began emerging from long imprisonments imposed by the Nasser regime, many of them were now in their 50s and had lost touch with the Egyptian street, particularly with its young generation. In fact, the younger Islamists had already been drawn to the writings of Sayyid Qutb, whose book, Ma’alim ‘ala Al-Tariq (referred to earlier), which was outlawed in Egypt, has become a primer for all radical Islamic movements. Sadat, who considered the Nasserites and the leftists as his principal enemies, overlooked the looming danger from the Islamic extremist movements that were advocating the violent overthrow of the regime and the establishment of a new regime founded on fundamental Islamic principles. These radical Islamic movements, operating under Sadat’s benevolence, would soon consume him. The Islamist movement itself lived to regret the assassination of Sadat which unleashed a severe reprisal against them. In the words of Al-Zawahiri:

“After Sadat’s assassination the torture started again, to write a new bloody chapter of the history of the Islamic movement in Egypt. The torture was brutal this time. Bones were broken, skin was removed, bodies were electrocuted and souls were killed, and they were so despicable in their methods. They used to arrest women, make sexual assaults, call men with women’s names, withhold food and water and ban visits. And still this wheel is still turning until today.The Egyptian army turned its back toward Israel and directed its weapon against its people.”[35]

Although not directly involved in the planning for the assassination of Sadat (whom he characterizes as an American agent) Al-Zawahiri alleges that the attempt on Sadat’s life was part of a larger plot to liquidate as many of Egyptian leaders as possible. In reality, no one but Sadat was assassinated. Al-Zawahiri also relates the attempt to assassinate President Husni Mubarak on his way to perform the Eid prayers in a mosque. The presidential motorcade took a different route and the attempt had failed.[36]

Al-Zawahiri Shifts His Vision and Activity Abroad

Al-Zawahiri’s association with Afghanistan, which eventually led to his alliance with bin Laden, started a little over a year before his arrest in connection with the assassination of Sadat. While holding a temporary job in Al Sayyeda Zaynab clinic, operated by the Muslim Brotherhood in one of Cairo’s poor areas, Al-Zawahiri was asked about going to Afghanistan to take part in a relief project. He found the request “a golden opportunity to get to know closely the field of Jihad, which could be a base for Jihad in Egypt and the Arab world, the heart of the Islamic world where real battle for Islam exists.”[37]

He spent the next four months in Peshawar, Pakistan. For him, this experience was providential because it opened his eyes to the wealth of opportunities for Jihad action in Afghanistan. His previous attempt to find a base for a Jihad movement in Egypt was not successful because, he says, “the Nile Valley falls between two vast deserts without vegetation or water which renders the area unsuitable for guerilla warfare, and which also made the Egyptian people submit to the central authority.”

Al-Zawahiri completed his prison term at the end of 1984. In his memoirs he writes that for personal reason he was unable to leave Egypt until 1986 to rejoin the jihad in Afghanistan. Thus, in 1986, he left Egypt for Saudi Arabia under a contract with Ibn Al-Nafis Hospital. However, he would soon depart to Pakistan to join the thousands of so-called Arab Afghans who flocked to Peshawar to help the Afghan Mujahedeen fight the war against the Soviet Union. In his second trip to Peshawar, he worked as a surgeon in the Kuwaiti Red Crescent Hospital. Eventually, he would go to the war zone for three months at a time to perform surgeries on wounded fighters, often with primitive tools and rudimentary medicines. At the same time, he opened the “Islamic Jihad” bureau in Peshawar to serve both as a liaison point for new Mujahedeen and a recruitment agency. Peshawar itself was both a gateway city and staging ground for the Mujahedeen.

In Afghanistan, Al-Zawahiri would find the perfect place for his Jihad movement to gain “operational, military, political and organizational” experience. In Afghanistan, Muslim youth fought a war “to liberate a Muslim country under purely Muslim banners.” For him, this was a significant matter because everywhere else wars were fought under “nationalist banners mingled with Islam and sometimes even with leftist and communist banners.” The case of Palestine, he says, is a good example where banners got mingled and where the nationalists allied themselves with the devil and lost Palestine. For Al-Zawahiri, when wars are fought not under pure Islamic banners but rather under mixed banners, the boundaries between the loyalists and the enemies get confused in the eyes of the Muslim youth. Is it, he asks, the external enemy who occupies the land of Islam or the internal enemy who prevents the rule of Islam and “spreads debauchery and decay under the banner of progress, freedom, nationalism and liberation?” In Afghanistan, the picture was very clear: “a Muslim people fighting [a Jihad] under the banner of Islam against an infidel external enemy supported by corrupt internal system.” He went on to write:

The most important thing about the battle in Afghanistan was that it destroyed the illusion of the superpower in the minds of the young Muslim Mujahedeen. The Soviet Union, the power with the largest land forces in the world, was destroyed and scattered, running away from Afghanistan before the eyes of the Muslim youth. This Jihad was a training course for Muslim youth for the future battle anticipated with the superpower which is the sole leader in the world now, America.[38]

The Struggle with Competing Islamist Groups

In 1988, three leaders of the Al-Jama’a Al-Islamiyya, which was in disagreement with Al-Zawahiri’s Islamic Jihad, arrived in Peshawar from Egypt, headed by Muhammad Shawqi Al-Islambuli, the brother of Sadat’s assassin, Khaled Al-Islambuli, to challenge Al-Zawahiri. The Al-Islambuli’s group was funded by Saudi Arabia. Soon conflict erupted between these two extremist groups, the Jama’a and the Islamic Jihad, particularly with the publication of a magazine called “Al-Murabitoon” by Al-Jama’a, and another magazine, Al-Fath by Al-Zawahiri. Al-Murabitoon accused Al-Zawahiri of depositing in his Swiss bank account money he had collected to support the Mujahedeen. He was also accused of selling arms provided by bin Laden and using the proceeds to buy gold nuggets. In the face of these accusations, some relief agencies decided to cut off their aid to Al-Zawahiri, and the need for funds forced him to seek assistance from Iran. This move further alienated the Gulf countries, particularly, Saudi Arabia which henceforth channeled all its aid to Al-Jama’a. By the time the Soviet Union started pulling out of Afghanistan in 1992 the conflict between the two groups reached the stage of mutual accusation of Takfir, or apostasy, and individual acts of assassination. Al-Zawahiri emerged the winner from this conflict, largely because of bin Laden’s support and because of the murder of Abdallah Azzam, the spiritual leader of bin Laden.

Militant Jihad: the New Paramount Ideology

In Peshawar, Al-Zawahiri drew a strict distinction between his movement, the Islamic Jihad, and other competing Islamist movements; for example, Al-Jama’a Al-Islamiya and, to a lesser extent, the Muslim Brotherhood movement. In his book, Al-Hisad Al-Murr (The Bitter Harvest) Al-Zawahiri articulates his violence-driven and inherently anti-democratic instincts. He sees democracy as a new religion that must be destroyed by war. He accuses the Muslim Brotherhood of sacrificing Allah’s ultimate authority by accepting the notion that the people are the ultimate source of authority. He condemns the Brotherhood for renouncing Jihad as a means to establish the Islamic State. He is equally virulent in his criticism of the Al-Jama’a Al-Islamiya for renouncing violence and for upholding the concept of constitutional authority. He condemns the Jama’a for taking advantage of the Muslim youth’s enthusiasm which “it keeps in its refrigerators as soon as the young people have joined its movement or seek to direct them toward conferences and elections (rather than toward Jihad).”[39]

Al-Zawahiri takes his criticism a step further by characterizing the Muslim Brotherhood as “kuffar” (infidels.) Their adherence to democracy to achieve their political goals means giving the legislature rights that belong to Allah. Thus, he who supports democracy is, by definition, infidel. “For he who legislates anything for human beings,” writes Al-Zawahiri, “would establish himself as their god.” Since democracy is founded on the principle of political sovereignty, which becomes the ultimate arbiter of right and wrong, whoever accepts democracy is an infidel. He deplores the Muslim Brotherhood for mobilizing the masses of youth “to the ballot box” instead of mobilizing them to the ranks of Jihad. He criticizes the Brotherhood for extending bridges of understanding to the authorities that rule them. These bridges become part of a package or a quid pro quo: the rulers allow the Brotherhood a degree of freedom to spread their beliefs and the Brotherhood acknowledges the legitimacy of the regime. For him, those who have been endorsing this philosophy cannot be trusted even if they were to split from the Brotherhood. Their minds are forever polluted and set in stone.

Al-Zawahiri draws attention to the enormous financial wealth of the Muslim Brotherhood movement. This “material prosperity,” he argues, is the result of the Brotherhood’s leaders who escaped Nasser’s oppression and took over regional and international banks and businesses. Joining the Brotherhood, says Al-Zawahiri, guarantees the young recruits the means of making a living and, hence, their activities are driven more by materialistic than spiritual considerations.[40]

In his memoirs, “Knights under the Banner of the Prophet” Al-Zawahiri responds to the criticism leveled against him for his strident condemnation of the Muslim Brotherhood. While he concedes that, as a human being, he may have erred in some details, he still considers the Muslim Brotherhood to be a movement that grows organizationally but commits suicide ideologically and politically. One of the most visible aspects in the political suicide is their support of the election of President Mubarak in 1987. He goes on to use a medical metaphor to makes his point:

It is not expected of the physician to tell the patient that your brain is healthy and your heart is healthy and your kidneys are healthy and your other body parts are in good shape except your stomach which has a cancer. It is incumbent on the physician to tell the patient that his life is in danger from a serious disease and it is incumbent on the patient to start treatment quickly or he will face ruin.[41]

The Merger of the Jihad and Al-Qaeda

While the ideological war with Al-Zawahiri’s rivals was ongoing, the relationship between him, as the head of the Egyptian Jihad organization, and bin Laden, as the head of the Al-Qaeda, strengthened. The two have agreed that the Islamic Jihad should retain its identity as an essentially Egyptian organization while the Al-Qaeda was to remain a multi-national organization and, in time, it became the melting pot of the “Afghan Arabs”, or volunteers to the Mujahedeen ranks.

At the end of this war in 1990, Al-Zawahiri may have preferred to stay in Afghanistan but the new mujahedeen government in Kabul, under Burhan Al-Din Rabbani, sought to get rid of the “Afghan Arabs,” Al-Zawahiri thus looked for a reliable base to reorganize and, thus, he followed bin Laden to Sudan. Always security-conscious and secretive, to throw up a false trail he announced on his way to Sudan, that he was granted political asylum in Switzerland and when he returned to Afghanistan after three years in Sudan, he announced that he had selected Bulgaria as the country of asylum.

The New Base in Sudan

In 1989, a new Islamic Front, led by Dr. Hassan Turabi, took over power in Sudan and instituted a new Islamist regime which favored Islamic fundamentalist movements everywhere. It was a perfect environment for bin Laden and Al-Zawahri to establish bases in the country. Farms were purchased and converted into military training basis for four years, between 1992 and 1996.[42]

Bin Laden invested heavily in Sudan which was undergoing a severe economic crisis. His investments bought him and Al-Zawahiri a secure refuge and a number of their key followers. Al Zawahiri had become concerned that Sudan, under international pressure, might betray them for financial gains as it did in the case of Carlos (the Venezuelan Marxist terrorist). The two of them looked for a new base of operation and found themselves welcomed only by the new Taliban government in Afghanistan. However, Al-Zawahiri first went to Yemen where he established three boot camps-Badr, Al-Qadisiyya, and Maraqesha-which attracted volunteers from Egypt, Sudan, Afghanistan and even from some sub-Saharan African countries. The volunteers who were called “Talai’ Al-Fath” (the Vanguards of Victory) received training in guerilla warfare, including sabotage activities.

From Yemen Al-Zawahiri was involved in a number of terrorist initiatives. In 1994, he organized an attempt to murder the Egyptian Prime Minister Atef Sidqi in Cairo, but the attempt failed. He followed that attempt with another one to blow up a bus carrying Israeli tourists to the famous old bazaar in Cairo, Khan al-Khalili, at the height of the tourist season. This attempt also failed but resulted in the arrest of 107 suspects. Al-Zawahiri was successful, however, in blowing up the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan, for allegedly gathering information on the Jihad Movement. In his memoirs, Al-Zawahiri explains this event:

“We had to react to the Egyptian government’s expansion of its campaign against Egyptian fundamentalists outside the country. So we decided to target a painful goal for all the parties of this evil alliance. After studying the situation we decided to assign a group to react to this and we assigned their targets, first bombing the American embassy in Islamabad and if that wasn’t easy, then one of the American targets in Islamabad. If that didn’t work, then the target should be bombing a Western embassy famous for its historic hatred for Muslims, and if not that, then the Egyptian embassy. Our extensive and detailed surveillance found that targeting the American Embassy was beyond the abilities of the assigned group, so we decided to study one of the American targets in Islamabad, and we discovered it has few American employees and most of the victims would be Pakistani. We also discovered that targeting the other Western embassies was beyond the abilities of the assigned group, so we settled on targeting the Egyptian embassy in Islamabad, which was not only running a campaign for chasing Arabs in Pakistan but also spying on the Arab Mujahedeen.later, Pakistani security found in the ruins of the embassy evidence revealing the cooperation between India and Egypt in espionage.”

“A short time before the bombing the embassy the assigned group asked our permission. They told us they could strike both the Egyptian and American Embassies if we gave them extra money. We had already provided them with all that we had and we couldn’t collect more money. So the group focused on bombing the Egyptian embassy. The rubble of the embassy left a clear message to the Egyptian government.”[43]

Terrorism Against American Embassies in East Africa

Al-Zawahiri’s biggest success was sending his and Al-Qaida’s volunteers to Somalia to fight the American presence in that country and eventually causing the U.S. to withdraw. His volunteers fought under the command of a young Egyptian man, Ali Al-Rashidi, also known as Abu-Ubaida Al-Banshiri. From Somalia, Al-Banshiri was sent to Kenya to establish a base of operations for terrorist activities against the United States in East Africa. Al-Banshiri drowned in an alleged accident in Lake Victoria. After a period of uncertainty, Al-Banshiri was replaced by another Egyptian, Subhi Abu Sitta, also known as Abu Hafas Al-Masri who was responsible for organizing the bombing of the American embassies in Nairobi and Dar-Es-Salaam. In a final incarnation, Subhi Abu Sitta became Muhammad Atef, who was to become the field commander of Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. One of Abu Sitta’s daughters married bin Laden’s son, Muhammad, in January 2001. An American bomb killed Abu Sitta/Atef in Kabul in November 2001.

Toward the end of 1994 and early 1995 attempts were made by Al-Zawahiri, under the guidance of bin Laden, to coordinate the activities of the various Islamic terrorist movements to carry out sabotage activities against the United States in order to break its ‘hegemony’ in the Middle East. Meetings were held in Tehran, Khartoum and Cyprus (city unknown) with the participation of Imad Fadhia al-Mughniyah (of Hezbollah, wanted by the U.S. for murdering an American passenger on a commercial airliner and dumping his body on Beirut airport’s tarmac), Fathi Al-Shiqaqi (of Palestinian Islamic Jihad), Musa Abu Marzuq (of Hamas), in addition to Sheikh Abd Al-Majid Al-Zindani from Yemen as well as representatives from the Nahdha Movement in Tunisia, and Al-Jama’a Al-Islamiyya of Pakistan. In the last meeting, held in Khartoum in April 1995, Al-Zawahiri laid down three fundamental directions for the next stage of the struggle: first, increase the effectiveness of the Islamic networks in London and New York, particularly in Brooklyn; second, increase the effectiveness of the Islamic militias in the Balkans; and third, provide greater support to the armed Islamic groups in Somalia and Ethiopia.

The conferees agreed to establish a high-level coordinating body of the armed Islamic movements comprising Al-Zawahiri, Imad Fadhia Al-Mughniyah and Ahmad Salem. In less than a month, this body met in Cyprus and agreed to increase the number of volunteers to Bosnia and to ask Al-Zawahiri to visit the U.S. to see first hand the modus operandi of the Islamic networks there. Al-Zawahiri visited the U.S. in 1996 and helped raise a considerable amount of money for “the widows and orphans” of Afghanistan.[44]

Upon reestablishing themselves in Afghanistan in 1996, the two leaders bin Laden and Zawahiri began articulating the position of Al-Qaeda vis-à-vis the United States. They concluded that America was the Number One enemy of Muslims everywhere and that its support of some Arab regimes, mainly Saudi Arabia and Egypt, has been responsible for the failed efforts to topple those regimes. It was at the end of 1997 that bin Laden and Al-Zawahiri declared war on Americans everywhere, after an initial statement of war in 1996 against the American presence in the region only. Afterwards, the objectives were expanded. On 23 February 1998 bin Laden issued a declaration announcing the creation of “The World Islamic Front for Jihad against Jews and the Crusaders [Christians].” A Fatwa (edict) accompanied the declaration by bin Laden that “the killing of Americans -military and civilians-and the looting of their properties is a duty for Muslims everywhere.” In addition to bin Laden, the declaration was signed by Al-Zawahiri as leader of Jama’at al-Jihad and by Rifa’i Taha, the man in charge of the Advisory Council of the Islamic Movement in Egypt. From this union between Al-Qaeda and the Egyptian Jihad group “grew an apocalyptic vision that in many ways resonates more of Al-Zawahiri’s than of bin Laden’s”[45]

Soon after that, the group would establish a travel office in Egypt to facilitate the transport of volunteers to join the Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. The travel office was headed by Ismail Nasser Al-Din, who had spent 15 years in prison for terrorist activities in Egypt. His new title would become “Muhandis Tasfeer” or travel agent/facilitator. Egypt was only too happy to see her Islamic fundamentalists leave for the war in Afghanistan, hoping that they would be killed or at least would not return to Egypt. Many of these volunteers were trapped in places like Kunduz, Mazar Al-Sharif, and Tora Bora, not to be heard from again.

Trip to Chechnya and Prison in Russia

The looting of Al-Zawahiri’s computer after his escape from Kabul and its subsequent sale to a reporter of the Wall Street Journal have added enormously to our knowledge about Al-Zawahiri’s previously unknown activities. One such activity was his attempt to smuggle himself into Chechnya, his arrest by the Russian security police, his trial and subsequent release. This story is revealing and worth telling.

In the early morning hours of 1 December 1996, Al-Zawahiri, disguised as Mr. Amin with two operatives on fake Sudanese passports and a Chechen guide tried to cross the Chechen border in an attempt to establish a base in that territory. He was arrested at the border with his advanced communications equipment and a large sum of money in different denominations. During his trial in April, 1997, “he lied fluently and prayed frequently.” The judge had to call several recesses because of the “defendants’ disruptive piety.” When asked about the purpose of his visit he responded that “they wanted to find out the price for leather, medicine and other goods.” The Russian security policy which confiscated Al-Zawahiri’s computer at the time of his arrest had failed to read its Arabic content. Lacking other evidence, the Russian judge let them go free. Documents found on Al-Zawahiri by the Russians included “a visa application for Taiwan; a bank card from Hong Kong; details of a bank account in Guangdong, China; a receipt for a computer modem bought in Dubai; a copy of a Malaysian company’s registration certificate that listed Dr. Zawahiri under an alias, as a director; and details of an account in a bank in St. Louis, Mo.”[46]

Al-Zawahiri Summarizes His Achievements

In the introduction to his autobiography, Knights under the Banner of the Prophet, Al-Zawahiri writes:

“I wrote this book to convey the message to our generation and the generations to come. Due to these worrying circumstances and unsettled conditions I may not be able to write later. And I expect it will not be published by a publisher and distributed by a distributor. This book is an attempt to revive the consciousness of the Islamic nation, to tell them about their duties and how important these duties are and how the new crusaders hate Muslims and the importance of understanding the difference between our enemies and our friends.”

“This book is a warning for the evil powers targeting our nation that your defeat draws nearer daily and we are taking step after step to retaliate against you and that your fight with the [Islamic] nation is doomed to defeat and all your efforts will come to nothing but merely postpone the inevitable victory of our nation.”

“The battle has become international after all the powers of blasphemy united against the Mujahideen. I wanted to show in this book some of the details of this epic and to warn readers of this book that hidden enemies and their wolves and foxes are on the road and you should be wary of them.”[47]

In the book, Al-Zawahiri provides his version of the political situation in Egypt today. He says that there are two competing powers in the country – an official power and a popular power. The first is supported by America, the West, Israel and the majority of the Arab rulers. The second depends on Allah alone. It is spreading widely and is allying with the Jihad movements from Chechnya in the north to Somalia in the south and from Turkmenistan in the East to Morocco in the West. The hostility between the two powers arises from the attempt by the first power “to drive Islam out of all spheres of life by force, tyranny and forged elections.” But despite all of this, Al-Zawahiri lists “the harvest” of the Jihad movement in the years between 1966 and 2000:

The spread of the movement, particularly among the youth.

The confrontation with the enemies of Islam "to the last drop of its blood".

The continuing sacrifice of tens of thousands of Muslims-- injured, arrested and killed.

The internationalization of the struggle against Islam after America has become convinced that the Egyptian regime cannot, by itself, stand up to the fundamentalist movement.

The continuation of the battle. The Islamist movement is either in an attack mode or in the preparation for an attack.

The Islamist movement has been able to articulate its principles based on the Koran and the religious scholars.

On the negative side, Al-Zawahiri lists the following difficulties:

Poor planning and preparation for Jihad activities. Despite successes, such as the assassination of Sadat, the movement should avoid randomized actions.

The lack of populist sermons... Most sermons are directed at the educated people. Given the restrictions on spreading the call for the Jihad it is particularly important to address the masses.

The reluctance of some movement leaders to continue armed confrontation. As an example, Al-Zawahiri mentions the decision by the Al-Jama'ah Al-Islamiyyah in Egypt in 1997 to suspend all armed action against the regime.On balance, Al-Zawahiri concedes that the movement has failed to establish an Islamic regime in Egypt.

Suicide Operations – The Most Effective Way of Harming the Opponent

In the last chapter of his book, Al-Zawahari examines the future of the Islamic movement in the world, in general, and in Egypt, in particular, and reaches the following conclusions:

The internationalization of the battle: The enemies of Islam have mastered the following instrument to fight it: (1) the United Nations; (2) the loyal rulers of the Islamic peoples; (3) the multinational corporations; (4) the international communications networks; (5) the international news agencies and media networks; and (6) the international relief agencies which are used for “spying, proselytizing, planning coups and transferring weapons.”

Against this alliance, stands the Islamist alliance comprising of the Islamist movements in the entire Islamic world. These movements are growing outside the new world order, under the banner of Jihad for the sake of Allah, freed from Western imperialist domination and from the apostate countries of America, Russia and Israel.

Also, against this alliance, stands the Islamist alliance of Jihad movements in the various Islamic countries and in the two countries that were “liberated in the name of Jihad for the sake of Allah (Afghanistan and Chechnya.)” This alliance, while “still in its infancy,” is growing rapidly and multiplying. It is a new force “outside the new international order, and liberated from the domineering Western enslavement”:

[There is] No solution but through the Jihad. This awareness is spreading amongst the new community of Islamists. What stand behind this spread of the new awareness is the viciousness “of the new crusade and Jewish war which treats the Islamic nation at utmost contempt.” Al-Zawahiri calls on the Islamic movement to acquire the qualities of steadfastness, perseverance, patience and adherence to principles. The leadership must serve as an example.Al-Zawahiri warns that “the victory of the struggle of the Islamic movement against the international alliance will not be accomplished without acquiring an Islamist base in the heart of the Islamic world.” He acknowledges that the creation of an Islamic state in the heart of the Islamic world is not an easy target to be achieved, or soon. However, it is the aspiration of the Islamic community to restore the caliphate and renew its vanished glory.

Al-Zawahiri is prepared, however, to sacrifice his call for perseverance and steadfastness in favor of self-preservation. What happens, he asks, if the movement’s membership or its plans were discovered and its existence was in danger, and what if its resources were confiscated? “The answer in my view,” asserts Al-Zawahri, “is that for the movement to withdraw as much as it can to a safe place and carry the war against the Americans and the Jews in their homes and against their bodies.” When that occurs, “the masters in Washington and Tel-Aviv” will blame their agent-regimes for their failure to deter these attacks and force them to wage a war against the Muslims which would turn the war into a war against the infidels. He concludes with a vision of conflict on a world scale:

“The Crusader-Jewish alliance under the leadership of America will not permit any Muslim power to govern in any of the Islamic countries. It will mobilize all its resources to strike at the (Islamic power) in order to remove it from governing.The alliance will wage a war worldwide.We have to prepare ourselves for a battle not only in one region but a battle that will include both the internal enemy [ruling government] and the external Crusader-Jewish enemy.”[48]

Bin Laden Talks about September 11th

After the events of 11 September, Al-Qaeda jumped on the Palestinian bandwagon to appeal to the Arab masses. In a video statement on Al-Jazeera television, bin Laden, with Zawahiri at his side, all but admitted his responsibility for the terrorist attacks on September 11th by praising the perpetrators as martyrs. After claiming that “Here is America struck by Allah the Almighty in one of her vital organs,” he went on to state that “Allah has blessed a group of vanguard Muslims, the forefront of Islam, to destroy America. May Allah bless them and allot them a supreme place in heaven.” Palestine was next. In bin Laden’s words: “In these days, Israeli tanks rampage across Palestine, in Ramallah, Rafah, and Beit Jala and many other parts of the land of Islam, and we do not hear anyone raising his voice or reacting. But when the sword fell upon America after 80 years, hypocrisy raised its head up high bemoaning those killers who toyed with the blood, honor and sanctities of Muslims.”[49]

Next, it was Al-Zawahiri’s turn to speak on al-Jazeera T.V. On November 9, 2001, he had this to say: “Bush lies to his people when he claims to have destroyed the Al-Qaeda group and broken the ranks of the Taliban. The whole world laughs at his lies.” He went on to assert that “our Jihad, with the help of Allah, will continue until we liberate our holy places from the American-Jewish aggression in Palestine and the rest of the Arab world.” He concluded his speech by promising more blows to America.[50] In a recent interview with the Pakistani newspaper “Jang” Al-Zawahiri is quoted as saying that “Tel-Aviv is our next target.”[51]

Islamists Respond to Al-Zawahiri’s Memoir

Taking issue with Al-Zawahiri’s criticism of personalities and events associated with this movement, the lawyer for the Islamic movement in Egypt, Muntasir Al-Zayyat, wrote a rebuttal in a book titled “Al-Zawahiri as I Knew Him” which was serialized in the other London-based, Saudi newspaper, Al-Hayat, from January 10-17, 2002.

Although his response is mostly polemical, Al-Zayyat provides considerable insights on three issues: first, the primary motivation for Zawahiri’s departure for Afghanistan; second, operational failures; and, third, the influence of the bin Laden-Al-Zawahiri alliance on the Islamic movement in Egypt in particular and on Islam, in general.

The Departure for Afghanistan