Syrians are move to camps described as “large prisons” in southern Turkey, where they are persuaded to return to Syria, according to Syria TV.

The pace of deportation of Syrian refugees from Turkey to northern Syria has increased during the past year, and the selection of deportees was semi-random. Most of the deportees hold temporary protection cards (Kimlik, in Turkish) and work permits. Human Rights Watch called on Turkey not to force people to return to places where they face serious danger, and to protect the basic rights of all Syrians, regardless of where they are registered. It also called for not deporting refugees who live and work in a city other than the one where their identities and temporary protection addresses were registered. However, the Turkish Presidency of Immigration said that the allegations of Syrians being forced to return without legal basis do not reflect the truth. It added that, in voluntary return procedures, Syrians sign return forms in the presence of a witness; they are also directed to the border crossings from which they want to exit.

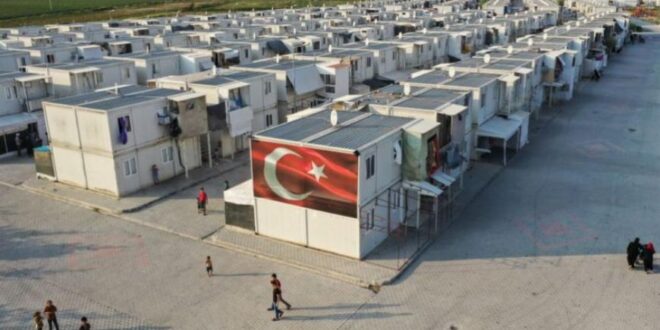

Signs of deportation usually appear after the Syrian person in question is arrested from his place of work or on public roads, then taken to a deportation center. After this, deportees move to camps described as “large prisons” in southern Turkey, which contain thousands of Syrians who were offered two options: either to stay in the camps or to sign voluntary return papers. And here, the psychological factor plays its role — especially in light of the fact that a lawyer is not allowed.

Based on what deported Syrians told Syria TV, the acquittal of any Syrian accused of committing a crime — whether large or small — does not lead to his freedom. This is because the police take the person from the station or court to Turkish immigration, which then determines the person’s fate. And so, the person is either deported or released.

Deportation centers in Turkey

“Samer” (a pseudonym), a young Syrian man, said that he was surprised that his temporary protection card was cancelled, so he asked for an appointment to update his data. Since this procedure could take a long time, he began to move based on his expired work permit.

The passage of “Samer” from the province of Osmaniye, southern Turkey, coincided with a campaign carried out by the Turkish authorities to combat immigration. So he was stopped at a checkpoint equipped with a bus to transport detainees, where he was asked to get out of the car. After that, three security personnel took him to the station. Upon his arrival, the authorities confiscated his mobile phone and then ushered him into an interrogation room for questioning. There, the authorities invited him to sign the voluntary return papers, but he refused on the grounds that he had been in Turkey for six years, accompanied by his family.

“Samer” told the Syria TV website that, on the second day, he went with the security forces to the immigration branch in the province of Osmaniye. There he faced poor treatment and was also asked to sign the papers to return to Syria or go to the Osmaniye camp. Samer chose to go to the camp, hoping to remedy the matter by communicating with lawyers.

The camp is divided into three categories, and it contains women and children. In one of the sections there are – according to Samer – military vehicles, alarms, a security cordon, guard points and surveillance cameras, similar to barracks and military installations. This section contains about 1,000 to 1,500 people.

On the condition inside the camp, “Samer” says: “Some people spent six months in the camp, and they are still inside it. There are no medical centers or the capacity to be transferred to the hospital. It is forbidden to receive anything from family except money, and every day at midday, a military patrol comes and requests a meeting with all inmates. At the meeting, work is done to convince the detainees to sign the voluntary return papers by spreading despair among them. They say: “You will never get out of here, no one will ask about you, and your only option to escape is to go to Syria.”

On a daily basis, about 20 people leave the camp towards Syria, after being persuaded to sign the return papers. Those who are convinced are taken to a special place to record a film, as young men who decided to return recently voluntarily. Work is being done to facilitate procedures, with the continued psychological pressure on others within the camp, without being allowed to engage a lawyer.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News