Turkey is increasingly relying on airpower in its fight against the PKK. New parties have been drawn into the conflict as it spreads to new theatres in Iraq and Syria, which, for now at least, complicates potential efforts to settle things down.

Early February brought a fresh demonstration of the new air-war tactics that Turkey is increasingly using in its fight with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – its enemy in some four decades of conflict. Turkey, like the U.S. and European Union (EU), designates the PKK a terrorist group. On 2 February, some 60 Turkish fighter jets carried out a coordinated attack on training camps, shelters and ammunition storage facilities used by the PKK and its affiliates in northern Iraq and Syria. Since mid-2019, Turkey has increasingly relied on airpower, including drones, to hit PKK bases in the rugged mountains of northern Iraq, allowing it to kill higher-level PKK cadres. According to data collected by Crisis Group, the Turkey-PKK conflict has claimed more than 5,850 lives since a two-and-a-half-year ceasefire broke down in July 2015, inaugurating one of its deadliest chapters.

The spread of fighting to new battlegrounds has drawn in an increasingly complex web of actors. In northern Iraq, Turkey has partnered with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) – the largest and most powerful political party in Iraqi Kurdistan and its Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) – to obtain information about PKK movements as well as to secure areas it has cleared of PKK militants. The PKK, meanwhile, is forging deeper alliances with Iran-backed Iraqi paramilitary groups (also known as Hashd al-Shaabi) at odds with Ankara and is exercising increasing decision-making authority within the ranks of its affiliates in Syria, primarily the People’s Protection Units (YPG), which Turkey sees as an extension of the PKK. The expansion of the battlefield, use of new tactics and involvement of new actors make it harder to identify avenues for tamping down the conflict. Still, steps to contain escalation between the YPG on one side, and Turkish forces and Turkey-backed rebels in northern Syria on the other could help reduce the risk of more violence. So, too, in Iraq, could progress on the Sinjar agreement, an accord signed between the Iraqi government and the KRG in October 2020 that lays out steps related to governance and security in Iraq’s Sinjar district and may address some of Turkey’s concerns about the presence of the PKK there, though for now resistance from the PKK and groups aligned with it to the deal’s implementation remains a challenge.

ACLED tracks a wide variety of political events, including protests, armed clashes, looting and non-violent transfer of territory. For purposes of this analysis, “violent incidents” are defined as those in the following ACLED sub-event types: “air/drone strike”, “armed clash”, “grenade”, “remote explosive/landmine/IED”, “shelling/artillery/missile attack”, “suicide bomb” and “attack”.

Turkey’s New Tactics

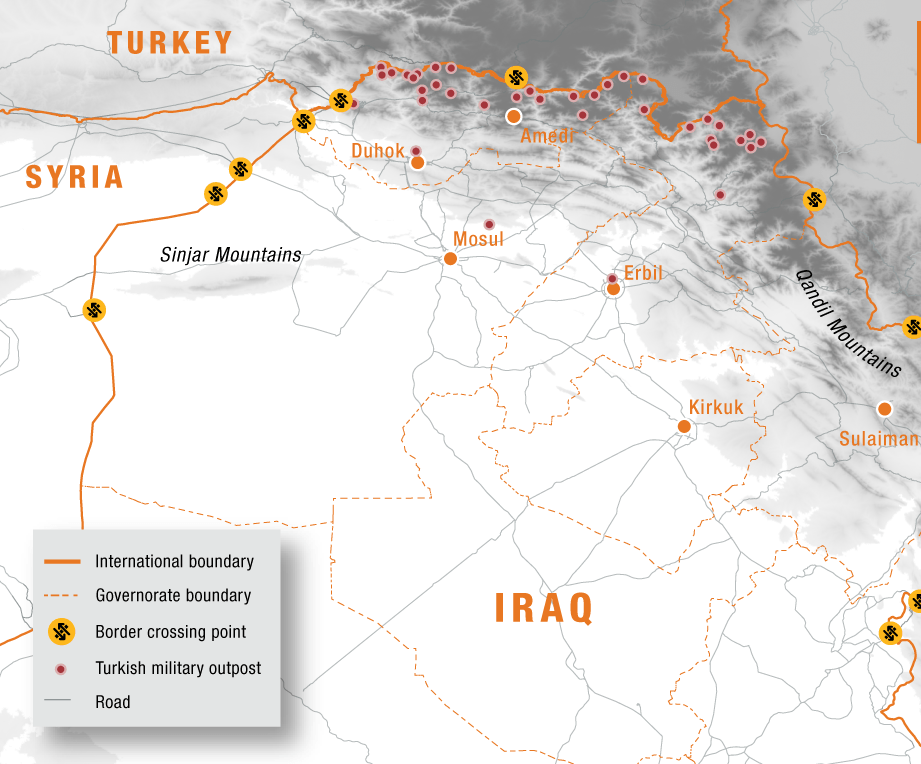

Turkey’s conflict with the PKK has progressed through several phases since hostilities resumed in 2015 (see Figure 2). The bloodiest fighting took place between 2015 and 2017 in Turkey’s majority-Kurdish south east, as Turkish forces sought to drive the group out of its strongholds over the course of roughly two years of urban warfare concentrated in a few districts of provinces such as Diyarbakır, Şırnak, Hakkari and Mardin (see Figure 3). By 2017, the fighting had moved to rural areas of the south east. As the Turkish military pushed militants out of Turkey, the battleground shifted to northern Iraq, where it was centred largely in areas governed by the KRG. Since July 2015, roughly one in six deaths in the conflict have occurred in Iraq, the majority of them PKK militants. With the KRG’s acquiescence, Turkey now has 2,000-3,000 troops stationed at around 40 outposts in northern Iraq, some as far as 40km from the border, Turkish security analysts estimate. This deployment comes on top of the estimated 8,000-10,000 Turkish troops garrisoned in three pockets of northern Syria: one in Afrin, a second between Azaz and Jarablus in the north west, and a third between Tel Abyad and Ras al-Ain in the north east.

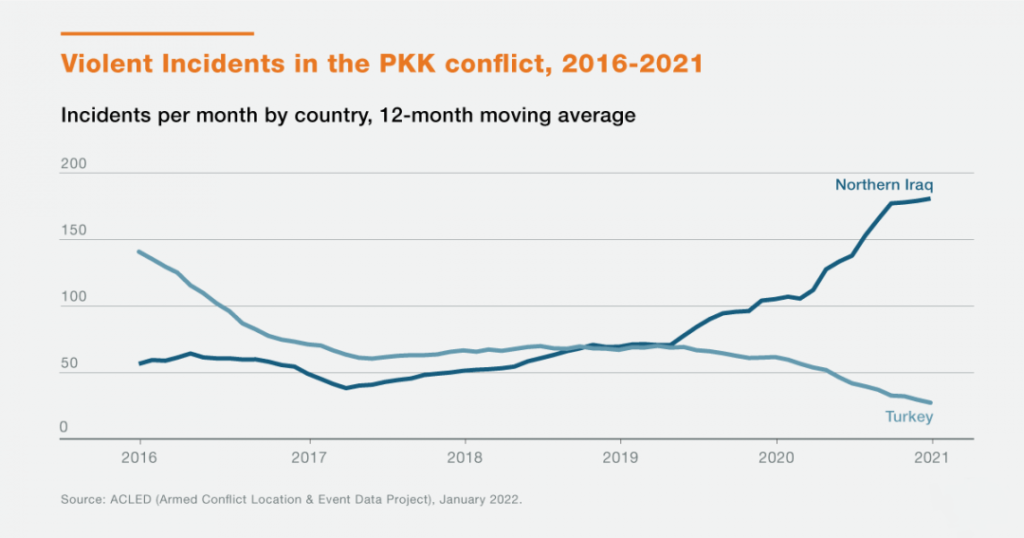

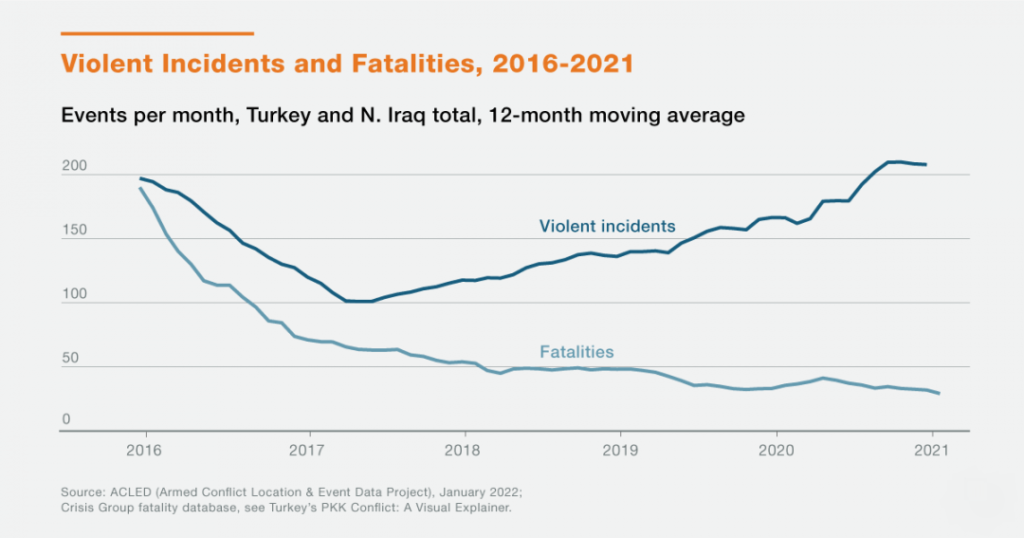

The conflict’s operational tempo reached a new peak in 2021, with more violent incidents than in any comparable period since the ceasefire broke down – including airstrikes, firefights, roadside bombings and rocket attacks – according to open-source data gathered by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). ACLED recorded a monthly average of 209 such incidents in Turkey and northern Iraq in 2021, exceeding the pace of violent incidents seen during the urban phase of the conflict between 2015 and 2017. Most of these incidents were Turkish airstrikes, with almost 1,200 in northern Iraq in 2021 alone. The higher incident rate is accompanied by a lower level of fatalities than in the conflict’s early years, when combat was concentrated in densely populated areas. Hostilities claimed an average of 40 people per month in 2021, most of them PKK militants, compared to 150 per month in 2016, according to Crisis Group’s data (see Figure 3).

The deployment of Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drones since 2017 has proven a game changer for Ankara, providing both armed overwatch for Turkish forces and enabling the targeted killing of higher-ranking PKK figures in hard-to-reach terrain in Turkey’s south east and northern Iraq. The PKK has long found refuge in the steep cliffs and jagged peaks of the Zagros mountain range stretching from the Iraq-Iran border to the Turkey-Iraq frontier. PKK training camps dot the region, including in the Qandil mountains of Iraq, where the group’s headquarters are located. Before it fielded the Bayraktars, Turkey had been using unarmed surveillance drones purchased from the U.S. and Israel in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Besides lacking strike capability, these drones were costly and had a more limited range than the Bayraktars, as well as less powerful cameras and transmission systems. Turkish officials also reportedly feared that because those drones were more easily detectable by countries with radar instruments in range – like Israel, the U.S. and potentially even Iran – their activities could more easily be monitored.

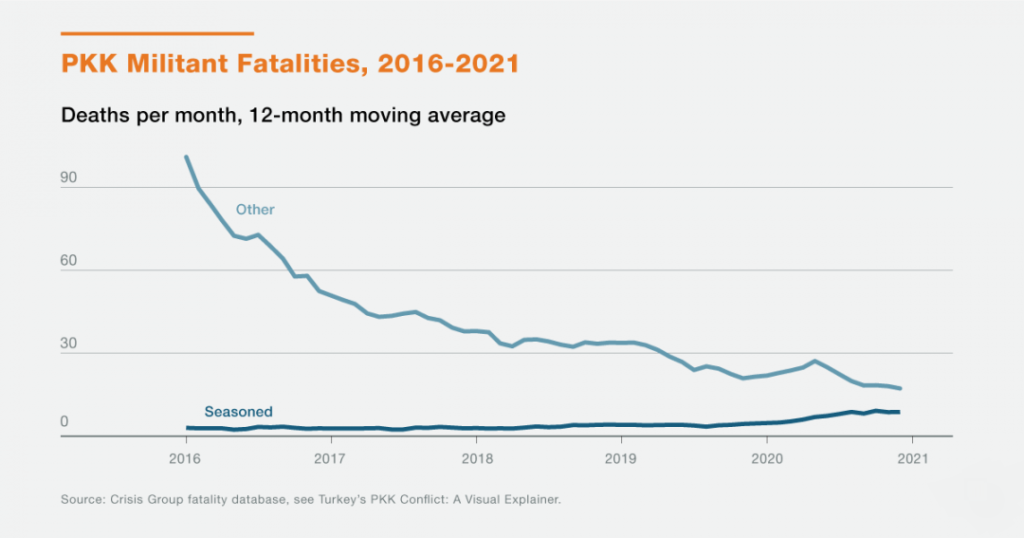

The use of more advanced and versatile drone technology has enabled Turkish forces, including ground units, to penetrate deeper into Iraqi territory and go after higher-ranking militants. Drone technologies offer more protection for forces on the ground and can increase their confidence and morale. Turkish troops have also been cooperating more closely with the KDP to gather better intelligence on militant movements and hideouts, and Turkish media are reporting the participation of Turkish intelligence agencies in anti-PKK operations in the area. Moreover, according to Crisis Group data, Turkey is killing an increasing proportion of militants whom the PKK itself classifies as commanders or regards as playing substantial battlefield roles as a share of total fatalities (see Figure 4). Crisis Groups categorises this group of militants as “seasoned”. In 2021, more than one third of the confirmed 312 PKK fighters killed were such seasoned militants. The ratio of killed PKK militants to killed state security force members has also risen more than fourfold in Turkey’s favour since July 2015.

Crisis Group has recorded 74 non-combatant deaths in violent incidents in northern Iraq since July 2015, based on local reports and open-source information, more than half of them after mid-2019 when Turkey intensified its air campaign. News reports from the ground also suggest that a few thousand villagers in the Amedi district, as well as hundreds more in the Duhok district, lost their homes and moved to villages or cities farther south. Civilians in the area complain of both heavy Turkish bombardment and PKK militants’ pressure on locals to provide shelter from air raids.

Turkish officials publicly deny any civilian casualties from airstrikes. They say the use of drones, by allowing for more precise targeting, has significantly minimised the risk of collateral damage. Amid the dominant nationalist discourse in Turkey, criticism of armed drone use is deemed unpatriotic. The technology’s seeming effectiveness in weakening the PKK in the last few years and its export to other battlefields – such as Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Libya and Ethiopia – have unleashed what some analysts call “techno-nationalism”, ie, a pride in technology as a source of strength abroad that helps the government rally nationalist supporters at home.

The Turkey-KDP Partnership

In northern Iraq, the Kurdistan Democratic Party has emerged as Turkey’s main local partner in its fight with the PKK. Turkish relations with the party hit a low point in 2017 when Ankara opposed the KDP’s failed referendum on independence for Iraq’s Kurdistan region. But their joint opposition to the PKK’s presence in the area and growing trade ties have helped patch things up. The KDP has allowed Ankara to set up military bases and expand its anti-PKK intelligence and other operations in the territory the KRG administers. Critically, it also offers Turkey its own battlefield intelligence as the KDP and its armed forces know the terrain and have a good grasp of the PKK’s tactics. At times, KDP-aligned security forces also step in to establish control of areas in northern and north-eastern KRG-controlled Iraq from which Turkish operations have driven PKK militants.

” The KDP’s military cooperation with Ankara is underpinned by growing economic interdependence. “

The KDP’s military cooperation with Ankara is underpinned by growing economic interdependence. In 2020, despite COVID-19 restrictions, trade between Iraq and Turkey reached nearly $20 billion, double what it was in 2019. Around 70 per cent of that commerce was with the KRG, in whose territory approximately 1,500 Turkish companies operate. Turkish construction firms have invested at large scale in infrastructure and transport projects, including highways and railways. Turkey is also an important transit country for KRG oil and gas. Around 450,000 barrels of oil per day were pumped in 2020 through two pipelines with terminals in Ceyhan, a port in southern Turkey. These economic ties give Turkey more leverage over the KDP.

But the KDP’s alliance with Ankara has also made it a target of PKK attacks. Tensions rose particularly quickly after mid-October 2020, when KRG security services accused the PKK of assassinating the head of its local security forces, Ghazi Salih, in Duhok province near the Turkish border. Since then, the PKK have twice attacked the KRG-Turkey (Kirkuk-Ceyhan) pipeline, briefly interrupting the westward flow of oil, in October 2020 and January 2022. They also claimed responsibility for a roadside bomb killing one KDP peshmerga in November 2020. More recently, in mid-January 2022, as clashes between PKK and KDP-allied groups in Syria became more frequent, KRG authorities decided to close the Samalka/Faysh Khabour border crossing between Syria and Iraq.

The PKK’s Response

Turkey’s evolving tactics have to some degree paralleled the PKK’s efforts to step up its influence in northern Iraq’s Sinjar district and in north-eastern Syria.

The rise and fall of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) enabled the PKK to expand its reach in northern Iraq and north-eastern Syria in the period that began in 2014, when ISIS established its self-declared caliphate in the region. Before that, the PKK’s presence in northern Iraq had been largely confined to the Qandil mountains and the Makhmour district (the latter home to a Kurdish refugee camp of 10,000) farther south. In the first part of 2014, ISIS took over parts of Iraq to the south west and west of the majority-Kurdish areas, including the city of Mosul. Then, in August 2014, the jihadist group attacked Sinjar, a majority-Yazidi district in the Ninewa province, where KDP peshmerga forces had largely been in charge since the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. The peshmerga withdrew, but the PKK – with help from local partners – stepped in shortly thereafter. With an assist from U.S. airpower, a combination of pro-PKK groups (the YPG and Yazidi Sinjar Resistance Units, or YBS) and KDP peshmerga forces – helped repulse ISIS in late 2015. After that, PKK elements established a presence in Sinjar’s west, while KDP peshmerga dominated its east.

Until the KDP attempted its independence referendum in September 2017, the district largely remained under the control of KDP peshmerga forces, while the PKK maintained a presence. Following the referendum’s failure, Iraqi federal forces pushed the peshmerga back from “disputed territories” – areas where both the central government and the KRG claim administrative authority – between Baghdad and Erbil, including Sinjar. Since then, the KDP has not been able to return to Sinjar. Instead, the district has become a PKK sanctuary, governed by an administrative set-up led by the YBS, which has links to the PKK as well as Iran-backed Iraqi paramilitaries.

As it is not far from the Syria-Iraq border, the PKK has also been able to use Sinjar as a hub for outreach into Syria. Operating from Sinjar, it forged tighter links with the YPG, its Syrian affiliate, which by 2017 had established its own self-described “autonomous administration” in north-eastern Syria. Washington and other outside powers back this administration in part due to the YPG’s major role in the anti-ISIS fight in Syria. International support not only allowed the PKK’s Syrian affiliate (along with non-Kurdish partners) to exercise governance in the country’s north east but also, in effect, put the YPG in charge of security in the area.

” Ankara worries that Sinjar has become a land bridge connecting the PKK in northern Iraq with the YPG and other affiliates in north-eastern Syria. “

Ankara worries that Sinjar has become a land bridge connecting the PKK in northern Iraq with the YPG and other affiliates in north-eastern Syria. Top Turkish officials have repeatedly vowed that they will not allow Sinjar to become a “second Qandil” –ie, another PKK bastion. To curb its reach in Sinjar, the Turkish military has ordered numerous airstrikes since 2020, targeting both PKK and YBS fighters. The PKK has taken advantage of the natural protection offered by the mountains, building tunnels and secure locations, and thus reducing the impact of Turkish strikes.

The Sinjar and Syria Fronts

The combination of Turkey’s stepped-up operations in northern Iraq and the PKK’s entrenchment in Sinjar has driven an escalation of tensions on both sides of the Syria-Iraq border.

In February 2021, Turkey threatened to launch a broader military operation in Sinjar when, in reprisal for a Turkish push into northern Iraq, the PKK executed thirteen Turkish citizens (including soldiers and police officers) whom it had kidnapped in Turkey in 2015 and 2016 and had been holding hostage in a cave. The incident stoked nationalist sentiment in Turkey, putting significant pressure on Ankara to react. On 15 February, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said: “From now on, nowhere is safe for terrorists, neither Qandil nor Sinjar nor Syria”. In another speech a month later, he said: “We may come there overnight, all of a sudden”. The PKK’s allies in Iraq were concerned. Expecting a Turkish offensive, the Iran-backed paramilitary groups deployed additional fighters to Sinjar, a move that Turkish pro-government media outlets saw as a clear sign that they were shielding the PKK.

Turkish officials say the possibility of a broadened military campaign will stay on the table until the KRG and the Iraqi federal government make progress on an October 2020 deal, backed by the U.S. and UN, that calls for the removal of actors from outside the district – including the PKK, its Yazidi affiliate the YBS and Iraqi paramilitaries – from Sinjar. The agreement envisions the establishment of a governance and security mechanism in which Baghdad, Erbil and displaced Yazidis would share responsibilities. The PKK and the YBS, along with the paramilitaries, reject the proposed deal, which if anything has pushed them closer together.

Meanwhile, as the PKK has lost ground in Turkey and parts of northern Iraq, its cadres have sought greater decision-making authority in areas controlled by the YPG in north-eastern Syria and recruited more fighters from among their Syrian affiliate’s ranks. “Northern Syria has almost become something like a pressure relief valve for the PKK. … The more Turkey squeezes the PKK in Turkey and Iraq, the more its cadres assert themselves in Syria”, a seasoned security analyst said. PKK-trained cadres embedded in the YPG in Syria increasingly appear to be in the driving seat in important decisions such as budget allocations, battlefield appointments and the deployment of military supplies in Syria. Also, in the last two years – in a likely attempt to make up for losses – the PKK enlisted numerous militants born in northern Syria, most of whom it sent to northern Iraq to fend off Turkish incursions. Over 14 per cent of the PKK militants killed in Iraq and Turkey in 2020-2021 were born in northern Syria, the highest share Crisis Group has recorded since July 2015. In fact, in the four years of escalation before 2020 the proportion of Syria-born militants among the total killed was never above 2 per cent.

In the last two years, the YPG has also clashed with Turkish and Turkey-backed forces more frequently in northern Syria. Turkish officials believe the PKK is behind an increase in roadside bombs and rockets fired from YPG-held areas at Turkish troops and Ankara-backed rebels in Turkish-controlled pockets of northern Syria as well as a number of cross-border strikes into Turkey. Members of the YPG’s civilian affiliate, the self-declared “autonomous administration”, publicly distance themselves from these attacks, while Ankara blames them on PKK cadres from Qandil either embedded in or operating independently of the YPG. Yet the Turkish military has also launched drone strikes upon higher-ranking YPG members. Turkey’s above-referenced strike surge in early February 2022 hit YPG positions in northern Syria’s Derik as well as Sinjar and Makhmour in northern Iraq. For now, the U.S. troop presence in Syria’s north east and the leverage Washington has over both sides continue to play a restraining role, but more YPG attacks on Turkish forces could prompt Ankara to broaden its military campaign and upset the fragile status quo in the area.

Looking Ahead

” Turkey will almost certainly continue to rely on airpower to battle the PKK in Turkey, Iraq and Syria. “

Turkey will almost certainly continue to rely on airpower to battle the PKK in Turkey, Iraq and Syria, with all the repercussions that entails. Its military campaign supported by advanced drone technology has been effective in curbing the PKK’s presence in south-eastern Turkey and northern Iraq. But it has also fuelled intra-Kurdish rivalry between the KDP and PKK in northern Iraq, and exacted a toll on civilians living in the area, compelling some to leave their homes. It has also generated a response from the PKK, which has strengthened its ties with affiliated groups in both Iraq and north-eastern Syria. The result has been new clashes between Turkey’s security forces and groups it partners with on the one hand, and those working with the PKK and its affiliates on the other.

With the growing intensity of Turkey’s campaign against the PKK in northern Iraq and Syria drawing in new actors, a number of factors could stir up the already volatile mix. A U.S. withdrawal from north-eastern Syria for now appears unlikely but would remove an important check on the PKK’s targeting of Turkish forces and Turkey. While Turkey’s air campaign has taken out key PKK figures, it could breed resentment among the population and help the PKK recruit more fighters, particularly from new areas to which fighting has spread. It is also unclear how the approaching 2023 Turkish elections will play into calculations, whether pushing Ankara to step up its air campaign or the PKK to stand down in anticipation that more attacks might help the Turkish leadership rally nationalist supporters at home.

The risk of escalation is higher than the chances that things will settle down, but there are measures that the parties and their partners from outside the region can take to improve the odds. In Iraq, progress on the Sinjar agreement could go some way toward addressing Turkey’s security concerns, though its rivals’ outright rejection of the agreement’s current form for now hinders such efforts (a forthcoming Crisis Group publication will tackle this issue in more depth). In Syria, as argued in a November 2021 Crisis Group report, the U.S. could try to persuade its Syrian Kurdish partners and, by extension, the YPG to rein in attacks on Turkish troops and Ankara-backed rebels. It could also push Turkey to refrain from widening its military operations in the area, which – depending on the extent of the escalation such operations might provoke – could result in the displacement of civilians and complicate efforts to contain ISIS. Such measures will be difficult to advance and would only go some way toward defusing tensions, but they could still be helpful to eventually forestall new bouts of violence.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News