Spain remains a strong and dependable member of the EU and NATO and fully committed to the defence of Ukraine against Russian aggression.

Summary

Thirteen months on from the start of the invasion and partial occupation of Ukraine by the Russian Federation on 24 February 2022, Spain’s response has reflected the country’s position as a strong and dependable ally of NATO and as a Member State of the EU that is fully committed to the defence of their values and interests. This paper provides a concise analysis of the country’s main contributions during the first year of the war in terms of its political response, military cooperation and assistance, and economic and humanitarian aid.

Analysis

The political response

Before analysing Spanish reactions to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is important to put them in historical context. Prior to the outbreak of war, Spain and Ukraine had enjoyed modest but healthy bilateral relations. Ties were first established in January 1992, shortly after Ukraine’s declaration of independence, and were consolidated by a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, which entered into force in August 1997. More recently, Spain had become an important trading partner as the EU’s largest importer of Ukrainian cereals and the third worldwide. Some Spanish companies (such as Acciona, which has invested heavily in its renewable energy sector), had also established a presence in the country. In terms of relations between the two societies, following the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986, Spanish families began to welcome Ukrainian children during the summer holidays, becoming the third largest host after the UK and Germany. Furthermore, before the invasion there were already over 100,000 Ukrainian nationals living in Spain, which may go some way to explaining the decision of a further 170,000 to seek refuge in the country following Russia’s aggression.

Despite the above, some feared that, given Spain’s response to earlier Russian attacks against its neighbours, the Madrid government’s reaction would be lukewarm at best. After all, in August 2008, the Socialist Party (PSOE) executive led by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero had condemned Moscow’s occupation of the Georgian provinces of South Ossetia and Abkhazia somewhat half-heartedly, and Foreign Minister Miguel Ángel Moratinos had caused outrage in many Western capitals by urging Spain’s allies to recognise the new puppet state created by Russia as they already done with Kosovo.

Similarly, in 2014 the Popular Party (PP) government led by Mariano Rajoy was somewhat tepid in its condemnation of Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and the partial occupation of the provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk. Admittedly, the Spanish authorities immediately disavowed Moscow’s behaviour and expressed their support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and Spain was one of the first EU states to provide support for the Ukrainian army in the form of bulletproof jackets and helmets. Nevertheless, the Spanish government continued to hope that Moscow might somehow form part of a future European security architecture: for example, its new External Action Strategy, published shortly after the 2014 aggression, still contained references to Russia’s possible role as a ‘strategic partner’ of the Atlantic Alliance, in keeping with the NATO Strategic Concept adopted in November 2010. What was more, the Strategy openly questioned Crimea’s status as a Ukrainian territory, while recognising Russia’s ‘legitimate interests’ in the region.

Given this background, when Russia’s illegal and unwarranted invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, some feared that the pacifist inclinations of many PSOE voters and the fact that their coalition partner (Podemos) initially seemed to favour a diplomatic solution to the conflict instead of providing military support, would condition the response of the Pedro Sánchez government. However, this did not come to pass. Indeed, the policies implemented by the Spanish authorities over the last 13 months have confirmed Spain’s position as a firm and dependable ally of NATO and as a Member State of the EU that is fully committed to the defence Ukrainian national sovereignty and territorial integrity.

As soon as it became aware of the presence of Russian troops on Ukrainian soil on 24 February 2022, the Spanish government issued a forthright condemnation of the military invasion, stressing the importance of guaranteeing the coordination of EU partners and NATO allies to ensure ‘a response that reflected the severity of the illegal action’ of the Russian Federation.[1] The executive subsequently backed United Nations General Assembly Resolution ES-11/1, approved at an emergency session held on 2 March with 141 votes in favour, five against and 35 abstentions, which condemned the aggression and demanded Moscow’s immediate and unconditional withdrawal from Ukrainian territory. Spain also backed the United Nations Human Rights Council Resolution 49/1 of 4 March 2022, which created an independent international commission to investigate the invasion of Ukraine. Finally, Spain voted in favour of United Nations General Assembly Resolution ES-11/3, adopted on 7 April, suspending Russia’s membership of the UN Human Rights Council. The Spanish government has also refused to acknowledge the illegal referendums held in four regions of Ukraine, condemning Russia’s attempts to annex these territories and voting in favour of resolution ES-11/4 on 12 October, which decried these acts. Finally, it later supported a further resolution (ES-11/5) on 14 November 2022, demanding that Russia pay reparations for the significant material damage caused by the war.

As is also true of other EU and NATO members, the Spanish government has expressed its support for the Zelensky government and the people of Ukraine by undertaking several high-level visits to Kyiv, including those by Prime Minister Sánchez on 21 April 2022, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, European Union and Cooperation, José Manuel Albares, on 2 November, and the Minister of Defence, Margarita Robles, on 1 December. The prime minister returned to Kyiv on 23 February 2023, where he addressed the Ukrainian parliament.

In keeping with this, Spain has also adopted a favourable stance on Ukraine’s decision to apply for accession to the EU in February 2022. The Spanish government responded by expressing its willingness to support ‘the process for transformation and future accession to the EU’, albeit without providing any further details. It was not until shortly before the European Council held on 23-24 June 2022, when an agreement was reached to award Ukraine candidate status together with Moldova and Georgia, that Sánchez affirmed his unequivocal support for Kyiv’s request.[2] Spain is widely known for its enthusiasm for the cause of EU enlargement, provided the procedures (and conditionality) it requires are respected. In principle, support for Ukraine’s application is fully compatible with Spain’s long-standing commitment to the accession of the Western Balkans candidates. However, the government’s attitude could change if efforts to modify the procedures currently in place in order to expedite Ukraine’s accession were to succeed. In contrast, and like most NATO allies, the Spanish authorities refrained from responding to Ukraine’s request for urgent admission to the Alliance in September 2022, in reaction to Moscow’s formal annexation of four of its provinces.

The Spanish parliament has also been forthcoming in its support for the government and people of Ukraine. In response to an invitation by the President of the Congress of Deputies, Meritxell Batet, the Ukrainian President, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, appeared remotely before a joint session of the Spanish Cortes Generales on 5 April 2002, following similar appearances before the European Parliament and the legislative chambers of the UK, Canada, the US, Germany, Israel, Japan, France, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, Australia, Belgium, and Romania. In his speech, the Ukrainian leader invoked the bombing of Guernica by the Luftwaffe on 26 April 1937, one of the best-known episodes of the Spanish Civil War. Although this comparison appears to have pleased parliamentarians on the Left, it annoyed the far-right members of VOX, who regarded the atrocities committed by Russian troops against the civilian population of Bucha as being closer to the Paracuellos del Jarama killings carried out by the Republicans in December 1936. VOX parliamentarians were also displeased by Zelensky’s decision to name and shame several Spanish companies allegedly operating in Russia despite EU sanctions. Notwithstanding its opposition to sending arms to Ukraine, the Podemos parliamentary group responded enthusiastically to the speech.

The Spanish authorities have also been proactive when it comes to legal matters. When the atrocities in the city of Bucha came to light, Spain was among the signatories of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) that subscribed a request for the court’s prosecutor to investigate potential war crimes committed by the aggressor. At home, the Spanish government also pushed for the prosecution of Vladimir Putin, tasking the Chief Prosecutor of the Supreme Court with investigating Russia’s aggression against Ukraine on the grounds that Spanish citizens resided there. A Memorandum of Understanding was also signed between the Attorney General of Spain, Dolores Delgado, and her Ukrainian counterpart, Iryna Venediktova, to bolster judicial cooperation.

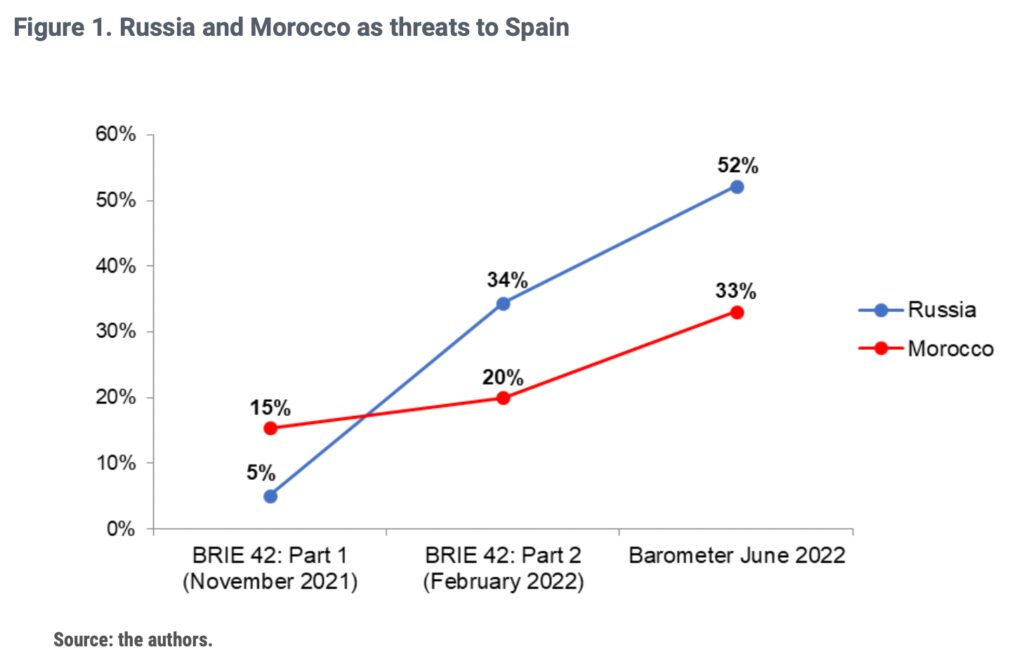

The political responses of both the government and the parliament are fully in tune with the concerns of the Spanish public. A survey by the Elcano Royal Institute carried out against the backdrop of an imminent invasion in February 2022 found that 34% of the Spanish public identified Russia as the biggest security threat facing the country, followed by Morocco (20%) and jihadist terrorism (14%).[3] Following the outbreak of the war, in the run-up to the NATO summit held in Madrid in June 2022, 85% of those surveyed by blamed Russia for the war and 52% identified it as the greatest threat to Spanish security. Furthermore, 58% of respondents stated that the most important issue facing Europe was not fuel prices or climate change but the war in Ukraine.[4] According to a study of public opinion carried out in Spain and France by the Elcano Royal Institute in October 2022, 54% of respondents continued to believe the EU’s biggest challenge or problem was the war caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[5] A recent Ipsos survey has found that Spain was among the highest ranking countries in terms of the attention paid to the war (75% of respondents), a figure that has remained constant over the past 13 months.[6]

The military response (and assistance)

The Spanish military response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine has been threefold: the commitment to NATO efforts; coordinated EU initiatives; and strictly bilateral measures.

As far as the Atlantic Alliance is concerned, prior to the outbreak of the war Spain was already fully committed to allied attempts to strengthen deterrence and defence on its eastern flank. Since the start of the conflict, its contribution in this area can be characterised as a series of adjustments to operations led by NATO and the troops and the equipment Spain provides as an ally.

Prior to the conflict, in December 2021, the Spanish government had already agreed to deploy six Eurofighters and 130 troops in the Graf Ignatievo airbase (Bulgaria) in February 2021 as part of NATO’s enhanced Air Policing mission.[7] Under the same mission, in October 2022 it deployed an AN/TPS-43M early warning radar near Constanța (Romania). In November and December 2022, Spain sent another six Eurofighters from wing 11 to the Bezmer airbase (Bulgaria), later deploying eight F-18s from wing 15 and 130 troops to the Feteștibase (Romania) in November.

The Spanish Armed Forces had already been participating with a rotating presence in the Baltic Air Policing (BAP) mission since 2006.[8] They had also been present in Latvia, as part of NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence (eFP),[9] and in Turkey, where they have had a battery of Patriot air defence missiles stationed on the border with Syria since January 2015. Other contributions include the deployment of permanent naval forces in the Black Sea since 2017. Following the invasion, the Spanish contribution to eFP in Latvia was reinforced, adding 250 troops to the 350 already deployed at the Ādaži base, alongside Leopard 2E tanks and Pizarro armoured personnel vehicles. Similarly, in June 2022, Spain provided a NASAMS air defence missile unit to the Lielvārde airbase (Latvia).

In terms of the Spanish contribution to BAP, in April 2022 eight F-18s were deployed with their respective crews and land teams to the Šiauliai base (Lithuania). In response to the Russian invasion, the detachment assumed new roles (including surveillance patrols on the borders of the Baltic states) and enhanced Vigilance Activity missions. Between August and September 2022, Spain also joined Germany on the BAP mission deployed at the Ämari base (Estonia), contributing four Eurofighters. In April 2023, Spain will also deploy a NASAMS air defence missile unit, which will operate from this base.

Lastly, several Navy ships were deployed as part of Spain’s contribution to the permanent naval forces in the Black Sea at the start of 2022. The resources made available to NATO are tasked with leading the deployment, redeployment, and coordination of support for NATO’s Standing Naval Forces (SNF) and monitoring the activities and operations of these forces.

Spain’s contribution to NATO’s deployment in its eastern neighbourhood can thus largely be characterised as a series of operational adjustments requested by the Alliance as part of the country’s routine contributions to deterrence and the defence of the eastern flank. In contrast, coordination with the EU has focused on sending both defensive and offensive weapons to Ukraine via contributions to the European Peace Facility. The facility, whose existence pre-dated the outbreak of war in Ukraine, was activated for this purpose by the General Affairs Council on 27 February 2022. The fund, which initially had a budget of €5.7 billion until 2027, had to be topped up with a further €2 billion in December 2022, after €3.1 billion were quickly allocated for arms procurement for Ukraine. According to the data provided by the Ministry of Defence, by December 2022 Spain had contributed €282 million to the fund.[10]

Likewise, a report on Spanish exports of defence materials, other materials and dual use products and technologies published by the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism calculated that the total value of these exports to Ukraine in the first half of 2022 was €209.7 million.[11] However, this source does not distinguish between private-sector Spanish munitions firms and military equipment provided by the Spanish Armed Forces since the outbreak of the war. During the first six months of 2022, Spain provided 155-mm artillery projectiles (56% of its total military exports to Ukraine), bombs, weapons of up to 20 mm, helmets, armour plating and 77,000 winter uniforms. Further supplies were also sent through the Polish logistics hub: heavy weapons, long-range and anti-tank munitions, emergency generators and technical equipment, an Aspide air defence battery and four Hawk missile launchers. According to the Spanish government, this was the largest ever package of military equipment ever provided to a third country.

In addition to supplying weapons and other military equipment, Spain has also been involved in training the Ukrainian Armed Forces. This has been undertaken by the Army training centre based at the Toledo Infantry Academy, as part of the EU Military Assistance Mission to Ukraine (EUMAM) and will run for an initial period of two years. Since November 2022, the centre has trained 400 Ukrainian soldiers every two months. Before that, small contingents of Ukrainian soldiers had also received training in the use of the Aspide air defence system at the Zaragoza airbase and the use of field artillery at the Álvarez de Sotomayor base in Viator (Almería). Although the Spanish military had already taken part in missions to train foreign troops in Mali, the Central African Republic and Somalia, this is the first time it has been provided on Spanish soil.

In addition to these contributions, Spain has also made a strictly bilateral contribution to the Ukrainian military effort by providing medical care to soldiers wounded in the war. Over 40 soldiers have received care since invasion began, half of whom have already returned to Ukraine. The Directorate-General of Defence Policy and the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration are processing accommodation for the remaining soldiers, to allow them to continue to receive outpatient care.

The possibility of sending tanks to Ukraine has undoubtedly been the aspect of Spanish military assistance that has attracted the greatest media and political attention. Curiously, Prime Minister Sánchez was the first international leader to raise the idea, so as to make up for a critical deficit in the Ukrainian war effort. At the start of the conflict, Spain had 347 Leopard tanks: two-thirds of these (239) were 2E models (equivalent to the German A6) and 108 were 2A4 models, which had been bought second-hand from Germany in 1995. Spain initially identified three options for sending tanks to Ukraine: (a) providing a company of modern 2E tanks (at least 14); (b) sending some of the 2A4 tanks currently deployed in Ceuta and Melilla; or (c) restoring to service some of the 2A4 tanks that had been in storage for a decade at Logistic Support Group 41 in Zaragoza. For both political and strictly military reasons, the third of these options seemed the most palatable. However, in August 2022 controversy ensued when the Ministry of Defence declared that the poor condition of the tanks stored in Zaragoza meant they could not be sent to Ukraine. Following the decision by the US, the UK and Germany to send 31 M1 Abrams tanks, 14 Challenger 2 tanks and 14 Leopard 2A4 tanks respectively, Spain announced it had asked Santa Bárbara Sistemas to repair six of the Leopard 2A4 tanks stored in Zaragoza, and during his visit to Kyiv in February 2023, Prime Minister Sánchez pledged to provide a total of ten tanks. In the midst of the debate about the number (and type) of tanks that would be made available to Ukraine, in January 2023 the Ministry of Defence initiated the transfer of 20 of its M113 armoured personnel carriers, a vehicle that is extremely versatile and easy to operate.

Spain has coordinated its military contribution to the Ukrainian war effort with its NATO allies and the EU via the US-led Ukraine Defence Contact Group (also known as the Ramstein group), to which some 50 countries belong. In contrast, the Spanish government has preferred not to join other initiatives, such as the creation of a group (comprising around 20 states and led by the special forces of the US Army) for the coordination of intelligence.[12]

Humanitarian aid

Long before the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of a large part of Donbas in 2014, in 2001 the EU had approved a directive for the temporary protection of displaced persons, which was not used until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Following a European Council decision in early March, Spain was one of the first Member States to invoke the measure. The directive awards the right to reside, work and have access to the social services normally available to any beneficiary of permanent international protection in EU Member States. Spain was not only swift to implement the measure, but extended protection to all those displaced by the war who had resided in Ukraine, regardless of their nationality (a measure on which the European Council did not reach agreement). It also extended this protection to all Ukrainians living in Spain before 24 February and who found themselves unable to return to their country. Another key aspect of this temporary protection has been the streamlined application system, which has received significant support from the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration.

Partly thanks to these measures, in early 2023 almost 170,000 Ukrainian refugees had received temporary protection and were living in Spain, 33% of whom were minors. This makes Spain the fifth largest destination for refugees, after Poland, Germany, the Czech Republic, and Italy. Furthermore, thanks to the joint efforts of the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training and the autonomous communities concerned, some 37,000 Ukrainian children are attending school in Spain, making this the fourth largest contingent of infants being schooled outside Ukraine.[13] Additionally, a significant number of Ukrainian children are currently in Spain receiving various forms of cancer treatment.

In terms of traditional humanitarian aid, Spain has contributed a package worth €38 million, the largest ever approved by the Spanish development aid agency (AECID). The sum includes a first shipment of 20 tonnes of medical and health supplies sent to Ukraine in late February 2022 in response to the Kyiv government’s request to the EU’s Civil Protection Mechanism. This was followed by a second shipment a month later, consisting of eight tonnes of medical and health supplies. AECID has also been used to channel the donation of transformers, lightning rods and generators to alleviate the energy shortages caused by continued Russian attacks on Ukrainian electricity infrastructure. These donations were made possible thanks to the generosity of Spanish companies such as Red Eléctrica Española (the Spanish electricity grid company), which have been keen to demonstrate their solidarity with the Ukrainian people. Additionally, the banking sector (including BBVA, Banco Santander, and Fundación La Caixa) has also donated sizeable sums for Ukraine to international bodies such as the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Looking to the future, in July 2022 the Spanish government participated in the Ukraine Recovery Conference in Lugano, at which it pledged to contribute €250 million in financial aid. In December, Spanish decision-makers attended the Paris Conference, which sought to coordinate efforts in Europe and beyond, together with international bodies, to streamline and consolidate aid to Ukraine to maximise its impact. At this meeting, Spain announced that when the immediate emergency created by the invasion had passed, Ukraine would be a priority for Spanish official aid in 2023, with AECID promoting an aid programme for the recovery and resilience of the country, in partnership with other multilateral bodies. The Madrid government subsequently approved a contribution of €2.7 million to the World Food Programme for the ‘Grain from Ukraine’ initiative to secure the passage of Ukrainian grain exports from Black Sea ports to Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Yemen and other countries that are particularly dependent on this source of food.

Previously, following the European Council meeting of June 2022, Prime Minister Sánchez had announced that Spain was working on a collaborative public-private project to allow the export of Ukrainian grain by rail, scheduled to begin in the second half of July. However, it was not until early October that the first –and so far, only– consignment of 600 tonnes of Ukrainian grain was sent to Barcelona, with the aim of complementing the maritime route opened in July, following the agreement reached thanks to the mediation of the United Nations. The Black Sea Grain Initiative has allowed Spain to receive 3.8 million tonnes of Ukrainian grain since August 2022 (a figure only surpassed by China, followed by Turkey and Italy), most of which it re-exported to third countries.

Economic aid

There are two main strands to the West’s economic response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. First, these countries have gone to great lengths to provide Kyiv with the economic aid needed to support its economy and prevent the collapse of its public administration. At the same time, a sweeping package of economic sanctions –the harshest ever approved against a third-party– has been imposed on Russian entities and individuals.

In terms of aid, in December 2022 the EU approved €18 billion to allow Kyiv to meet its economic needs during 2023. This complemented the macro-financial assistance programme promoted by the European Commission during the second half of 2022, which has provided €9 billion of highly concessional loans, to which Spain has contributed with guarantees of €320.8 million.

Spain has also contributed €100 million to the aid package announced by the World Bank, the first of three projects by the institution to respond to the most urgent tasks for repairing and restoring essential services damaged by the war. These projects stem from the Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment carried out jointly by the Ukrainian government, the European Commission and the World Bank in September 2022, which prioritise the health, energy and transport sectors.

At the same time, in December 2022, the EU adopted its ninth package of sanctions against Russia. The list of persons and legal entities who have had funds and financial resources frozen, alongside EU travel and entry restrictions, has been expanded over the last year. Trade restrictions have also been adopted, targeting specific products, companies, economic sectors and geographic areas.

The Spanish administration acted swiftly to set up ad hoc institutions and put channels in place to respond to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Even before the start of hostilities, in January 2022, Spain had established a coordination cell for monitoring the situation in the Ukraine, coordinated by the Department of National Security, which reports directly to the Office of the Prime Minister and is tasked with synthesising information and issuing a daily update for the chief executive. Similarly, to ensure adequate coordination of the Spanish response, on 2 February 2022 five working groups were created as part of the Situation Committee under the National Security Council of the Office of the Prime Minister. The groups are responsible for monitoring the sanctions approved by the EU and Spain; establishing a cybersecurity action plan at the national level; coordinating and supervising the process for receiving and processing individuals who have been temporarily displaced from Ukraine; cooperating in monitoring the energy contingency plan; and taking part in the EU’s contribution to rebuilding Ukraine. These bodies have made a significant contribution to the necessary coordination between ministries, autonomous communities, municipal authorities and civil society organizations (such as NGOs), facilitating a reasonably efficient use of the human and material resources available.

Spain’s responses: final remarks

Partly due to the moral clarity that has characterised a conflict marked by the brutality of Russia’s wholly unjustified and illegal invasion (including serious war crimes), as well as a result of the empathy that exists towards Ukrainians living or seeking refuge in Spain, the general public and political elites alike have been almost unanimous in their unequivocal condemnation of Russia’s aggression and the support they have offered to the Ukrainian people.

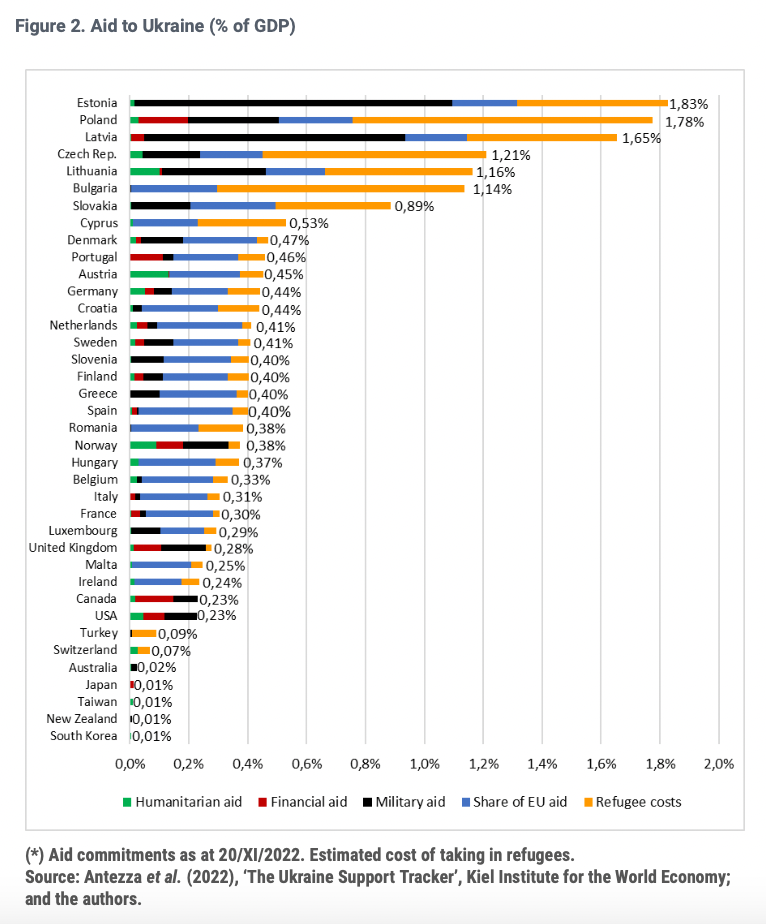

It is nonetheless important to reflect on the extent to which the response to Russia’s aggression over the last 13 months has lived up to the expectations befitting a country such as Spain. Based on the available data, if we measure this effort in terms of the cost of the military, economic and humanitarian aid provided to Ukraine so far (which amounted to 0.4% of Spanish GDP in 2022) and compare it to that of neighbouring countries, in relative terms Spain’s contribution is higher than that of France, Italy or the UK. When aid is measured as a percentage of national GDP, small countries benefit significantly compared to larger ones, while the converse is true –and even more pronounced– when measured in absolute terms. Nonetheless, Spain’s contribution remains larger than that of smaller, wealthier countries, such as Luxembourg, Belgium, Ireland, Switzerland, and Norway.

The available data also suggests that aid provided to Ukraine is largely correlated to countries’ geographic proximity to Russia, which determines both threat perceptions and the intake of refugees. Given the distance between Spain and Ukraine (Madrid is 2,863 kilometres from Kyiv, which is equivalent to a six-hour flight), it may be concluded that the responses of the Spanish authorities and the public at large have been highly satisfactory.

More than a year has elapsed since the Russian invasion of Ukraine began, and it is time to reflect on the potential for shifts in how the conflict will be perceived in Spain going forward. As already noted, at the outbreak of the war the country saw a spontaneous eruption of solidarity, with hundreds of families offering to host refugees fleeing the horrors of war. More recently, the war has resulted in an increase in electricity and food prices, and higher levels of inflation generally. Despite this, Spanish support for Ukraine remains undiminished.

According to polls conducted by ECFR, in May 2022, almost 50% of Spaniards wanted the war to end as soon as possible, even if this meant Ukraine having to give up control of some of its territory to Russia. By March 2023, however, this figure had dropped to 30%, while 29% believed that Ukraine needed to regain all its territory, even if this meant a longer war or more Ukrainians being killed and displaced.[14] According to Standard Eurobarometer 98, the fieldwork for which was conducted in January 2023, 89% of those polled believed the war was having serious economic consequences for Spain, and a further 73% claimed it was affecting them personally. Despite this, Spaniards expressed strong support for the humanitarian (96%), economic (82%) and military (65%) assistance provided to Ukraine by the EU thus far. Furthermore, 80% believed that, by opposing the Russian invasion, Europe was defending its own values. Interestingly, however, while 46% were satisfied with Spain’s response to the war, 49% were not.[15] This would suggest that many Spaniards would like their authorities to be even more forthcoming and generous in providing assistance to Ukraine in the difficult months (and possibly years) ahead.

[1] Office of the Prime Minister (2022), ‘El Gobierno de España condena enérgicamente la invasión militar de Ucrania por parte de la Federación Rusa’, Statement in response to the military invasion of Ukraine, 24/II/2022. [2] Other countries in the EU waiting room currently include Turkey (since 1999), North Macedonia (since 2005), Montenegro (since 2010), Serbia (since 2012) and Albania (since 2014). [3] Carmen González & José Pablo Martínez (2022), ‘42ª Oleada BRIE’, February. [4] Carmen González & José Pablo Martínez (2022), ‘Barometer of the Elcano Royal Institute. Special edition: War in Ukraine and the NATO Summit’, Elcano Royal Institute, June. [5] Carmen González & José Pablo Martínez (2022), ‘España y Francia: miradas cruzadas y actitudes hacia la Unión Europea y la guerra en Ucrania’, Elcano Royal Institute, October. [6] Ipsos (2023), ‘The world’s response to the war in Ukraine’, A 28-country Global Advisor survey, January. [7] Enhanced Air Policing is a defensive NATO mission which has been conducting surveillance and controlling Black Sea airspace since 2014. From the outset, Canada, Italy, Portugal, and the UK have deployed there to build training and operational relationships with the Romanian air force and jointly protect the Black Sea airspace. [8] Spain’s participation in BAP began in August 2006, with a detachment in Lithuania from which four Mirage F-1 units from wing 14 operated. This was followed by deployments of Eurofighters in 2015, 2016, 2018 and 2021, and F-18 units in 2017, 2019 and 2020. Spain has led four of these missions. [9] NATO’s enhanced Forward Presence is for defence and deterrence purposes. It is multilateral in nature and covers Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. It has been active since 2017, and by 2021 Spain had carried out eight rotations of its troops. [10] Margarita Robles statement to the Defence Committee of the Congress of Deputies, 21 December 2022. [11] Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism (2022), ‘Exportaciones Españolas de Material de Defensa, de Otro Material y de Productos y Tecnologías de Doble Uso elaborado por el ministerio de Industria, Comercio y Turismo, en el primer semestre de 2022’. [12] Caitlin M. Kenney (2022), ‘Three more nations join Ukraine planning cell run by Army Special Forces’, Defense One, 31/V/2022. [13] Department of National Security (2023), ‘España ante la invasión rusa de Ucrania: Gestión de la crisis en el marco del Sistema de Seguridad Nacional’, Cabinet of the Prime Minister, 24/I/2023. [14] Fragile unity: why Europeans are coming together on Ukraine (and what might drive them apart). Policy Brief. European Council on Foreign Relations, 16 March 2023. [15] Standard Eurobarometer 86, Winter Eurobarometer 2022-2023. Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News