“Murther, murther, murther, murther …” shouted Free-born John Lilburne from prison. “M’aidez, m’aidez,” says the international distress signal. Murder is the crime, and help is the need. That is the dynamic of the day, May Day. It’s methodology therefore requires answers to two questions: Who? Whom?

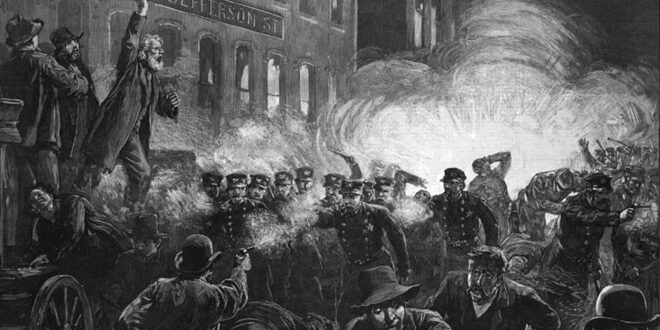

We remember los martiros, that is the martyrs who were hanged for their support of the Eight Hour Day and the police riot at Haymarket, Chicago. That struggle commenced on May 1st 1886. Who? Whom? The bosses hanged the workers. Their names were August Spies, Albert Parsons, Adolph Fischer, George Engel. Their hanging was judicial murder or state sponsored terror. “The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today.” Their last words, our prologue. The Haymarket hangings were preparation for mass murder at Wounded Knee (1890). Who? Whom? The army massacres the Lakotas.

The tendency of capitalism is the global devaluation of labor, an abstraction covering over the four-fold murders of war, famine, pestilence, and neglect that characterize our neo-liberal, incarcerating, planet-wrecking times. It is the widespread whisper, the secret thought, the unindicted accusation as more and more are shot, gassed, get sick, starve, drown, burn, or have to move out so that entrepreneuring gentry may move in. Call it expropriation, call it exploitation, combine them and you have X squared; add extraction and you have X cubed, or the formula of capitalism. No matter what you call it, we live in murderous times.

The time is out of joint—O cursèd spite,

That ever I was born to set it right!

Nay, come, let’s go together. (I.v.188-90)So, to all the Hamlets out there suffering from cursed spite, remember Shakespeare’s wise words, “let’s go together.” It’s May Day! The day of pleasure, the day of struggle. A day for the green, a day for the red. We want more time, as Linton Kwesi Johnson sings. More time in both senses referring to the years of our lives and to the seven generations hence. More personal time, more human/species/historical time.

The Maypole and the Hydra

Thomas Morton and a boat load of indentured servants arrived in Massachusetts in 1624. They settled in Passonagessit, or what became Merry Mount (modern day Quincy just south of Boston). In 1627 they celebrated May Day by erecting an 80 foot May pole. The following year the Puritans destroyed it and the settlement.

The Puritan Governor of Massachusetts, William Bradford, describes what happened. “They also set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing about it many days together, inviting the Indian women, for their consorts, dancing and frisking together, (like so many fairies, or furies rather,) and worse practices. As if they had anew revived and celebrated the feasts of the Roman Goddess Flora, or the beastly practices of the mad Bacchanalians. Morton likewise (to show his poetry,) composed sundry rimes and verses, some tending to lasciviousness, and others to the detraction and scandal of some persons, which he affixed to this idle or idol May-pole.”

The dance around the Maypole included former indentured servants from England, a Ganymede, several Algonquin people, youth and age, men and women. The dances were inspired by animals of the forest. Perhaps a morris dance or “Moorish” dance. Puritans had been fighting it for years. A poem was made, Bachanalia Triumphant, a year after its destruction, 1629

Nathaniel Hawthorne called it “that gay colony” where“jollity and gloom contended for an empire.” In his story, “The Maypole of Merry Mount” (1837), he describes “the Salvage Man, well known in heraldry, hairy as a baboon, and girdled with green leaves.” Twice he refers to rainbows once on the ribbon of the Maypole and once on the “scarf of a youth in glistening apparel.” Nathaniel Hawthorne alludes to the great central European Peasant’s Revolt a century earlier in 1526 when the rainbow was the sign of those fighting to retain access to the life-giving gifts of river and forest, the commons. Thus the rainbow was the earliest flag of the settler-indigenous encounter and suggests alternative to the bloody flag of war or the white one of surrender. Plus, it was emblematic of the commons.

Of May Day Philip Stubbes reported in The Anatomy of Abuses (1583), “I have heard it credibly reported (and that viva voce) by men of great gravity and reputation, that of forty, three score or a hundred maids going to the wood overnight, there have scarcely the third part of them returned home again undefiled. These be the fruits which these cursed pastimes bring forth.” The Puritan Christopher Fetherston fulminated against cross-dressing in his Dialogue Against Light, Lewd and Lascivious Dancing (1582). ‘For the abuses which are committed in your May games are infinite. The first whereof is this, that you do use to attire men in women’s apparel, whom you do most commonly call May Marions, whereby you infringe that straight commandment which is given in Deuteronomy 22.5. That men must not put on women’s apparel for fear of enormities.’

Puritans saw only “enormities” and “cursed pastimes.” These seem to have disappeared by the Victorian era. The poet Alfred Tennyson did much to domesticate the tradition with his long poem The May Queen (1855).

So you must wake and call me early, call me early mother dear,

Tomorrow’ll be the happiest time of all the glad New Year,

Tomorrow’ll be of all the year the maddest, merriest day,

For I’m to be Queen of the May, mother, I’m to be Queen of the May!May Day was becoming a children’s holiday. In Oxfordshire the kids were trying to turn it to advantage. They chanted.

Please to see my garland

Because it’s the First of May

Give me a penny

Then I will go away.Thomas Morton was the wildest person there according to Hawthorne. “Up with your nimble spirits, ye morris-dancers, green men, and glee maidens, bears and wolves, and horned gentlemen! Come; a chorus now, rich with the old mirth of Merry England, and the wilder glee of this fresh forest, and then a dance.”

Thomas Morton told the story. He did so in a book that could not be printed or published in England, The New English Canaan, published in Amsterdam in 1637. The English authorities confiscated four hundred of them on import. We don’t know that Free-born John Lilburne had a hand in the smuggling, though he might have since time and place were right. More anon.

The Green Man, that gentle soul of the earth and growing things, quite the opposite of the American AR-15 type of guy! A Green Man appears on the invitation for the coronation for King Charles III and Queen Camilla (the billionaires), designed by heraldic artist and manuscript illuminator Andrew Jamieson. Here it is on the invitation to attend next week’s coronation of Charles III.

The royal website explains this inclusion: “Central to the design is the motif of the Green Man, an ancient figure from British folklore, symbolic of spring and rebirth, to celebrate the new reign. The shape of the Green Man, crowned in natural foliage, is formed of leaves of oak, ivy and hawthorn, and the emblematic flowers of the United Kingdom.” A fertility figure or a nature spirit, similar to the woodwose (the wild man of the woods), and yet he frequently appears, carved in wood or stone in churches, chapels, abbeys and cathedrals.

Sculptures of Green Men provide curious ornamentation to medieval churches, universities, furniture, and fixtures – oak leaves disgorged from mouths, leaves sprouting from eyebrows, hawthorn leaves spewing from ears, nostrils, and eyes. Foliage crowns, leaf heads. They grimace, leer, smile, brood, or scowl. They make mischief or anguish and stir up mysteries making us think of Roman fauns, the wodewose or hairy wild man of the Dark Ages, the Hindu kirtimukha, or the Puck of the woodlands. The ancient Egyptian God Osiris is commonly depicted with a green face representing vegetation, rebirth and resurrection. Sometimes the figures of Robin Hood and Peter Pan are associated with a Green Man. The green man was adopted by Church and Monarchy as a kind of peripheral iconography. Green men ornament the quad of St John’s College, Oxford, that was commissioned by Archbishop William Laud, the would-be nemesis of Free-born John Lilburne.

The Puritan parliament in 1644 banned the erection of maypoles, declaring them ‘a heathenish vanity, generally abused to superstition and wickedness.’ Under Cromwell’s Protectorate the pendulum swung entirely in the Puritan direction; the May revels were shut down everywhere. In Oxford the antiquarian, Anthony Wood, reported: ‘1648 May 1. This day the Visitors, Mayor, and the chief officer of the well-affected of the University and City spent in zealous persecuting of the young people that followed May-Games, by breaking of Garlands, taking away fiddles from Musicians, dispersing Morrice-Dancers, and by not suffering a green bough to be worn in a hat or stuck up at any door, esteeming it a superstition or rather an heathenish custom.’

May Day celebrations, banned under the Commonwealth, were revived in 1660. When Charles II returned to England, common people in London put up maypoles “at every crossway”, according to John Aubrey. The largest was the Maypole in the Strand. The Maypole there was the tallest by far, reaching over 130 feet, half again taller than Merry Mount’s Maypole. It was blown over by a high wind in 1672, when it was moved to serve as a mount for the telescope of Sir Isaac Newton. Thomas Hobbes who tutored Charles II in math believed the Maypole was a left over from the time the Romans worshipped Priapus. The earliest reference to Maypole in England is time of the Peasant’s Revolt, 14th century.

The Maypole revelers were defeated Myles Standish and Governor Endicott. Morton was arrested, exiled, and imprisoned. The Maypole was toppled and the settlement burnt. The Maypole became a whipping post. Some are suspected of witchcraft, and whipped.

The Boston Puritans compared these folk to the many-headed Hydra. Frightened “Of Hydras hideous form and dreadful power … Hydra prognostics ruin to our state.” Morton was brought to trial, the Puritan magistrate deliberated.

Sterne Radamantus, being last to speak,

Made a great hum and thus did silence break:

What if, with ratling chains or Iron bands,

Hydra be bound either by feet or hands,

And after … lash’d with smarting rods,In addition to its several heads, no sooner was one cut off than others grew in its place. This was so frequent a charge against the landless people of the world, the crowds of its towns, and the ships’ crews in the era of settler colonialism and age of primary accumulation that Marcus Rediker and I took it as a symbol for the circulation of struggles among the various components of the nascent proletariat against their rulers and oppressors. Evidently we were not the first to do so!

We the working class, or we the people, or we commoners determine what we make and not just how we make it or who does the making, and that this is required in the face of climate change and what geologists term “planetary perturbations.” Human society must find its nature in an ecology that saves the waters, saves the soil, saves the air for purposes of life. This is why, as the Red Nation teaches us, indigenous sovereignty (Land Back!) and decarbonzation require us to look again at history with a view of the commons. Morton was among people who were commoning, bringing together various forms of mutuality based upon English celebration and indigenous commons. Here is Morton’s testimony.

“The more I looked, the more I liked it. And when I had more seriously considered of the beauty of the place, with all her faire endowments, I did not think that in all the known world it could be paralleled, for so many goodly groves of trees, dainty fine round rising hillocks, delicate faire large plain, sweet crystal fountains, and clear running streams that twin in fine meanders through the meads, making so sweet a murmuring noise to hear as would even lull the senses with delight a sleep, so pleasantly do they glide upon the pebble stones, jetting most jocundly where they do meet and hand in hand run down to Neptunes Court, to pay the yearly tribute which they owe to him as sovereign Lord of all the springs. Contained within the volume of the Land, [are] Fowles in abundance, Fish in multitude; and [I] discovered, besides, millions of turtledoves one the green boughs, which sat pecking of the full ripe pleasant grapes that were supported by the lusty trees, whose fruitful load did cause the arms to bend: [among] which here and there dispersed, you might see Lilies and of the Daphnean-tree: which made the Land to me seem paradise: for in mine eye t’was Nature’s Masterpiece.”Here is the green vision, idle for sure, idol not at all. Here’s what he says about dwellings (places for rest) and about shoes (needed for locomotion).

“The Natives of New England are accustomed to build themselves houses much like the wild Irish,” he says in lines that might as well have come straight out of Braiding Sweetgrass. “They gather poles in the woods and put the great end of them in the ground, placing them in form of a circle or circumference, and, bending the tops of them in form of an arch, they bind them together with the bark of walnut trees, which is wondrous tough, so that they make the same round on the top for the smoke of their fire to ascend and pass through; these they cover with mats, some made of reeds and some of long flags, or sedge, finely sewed together with needles made of the splinter bones of a crane’s leg, with threads made of their Indian hemp, which there grows naturally, leaving several places for doors, which are covered with mats, which may be rolled up and let down again at their pleasure, making use of the several doors, according as the wind sits. The fire is always made in the middle of the house, with windfall commonly, yet sometimes they fell a tree that grows near the house, and, by drawing in the end thereof, maintain the fire on both sides, burning the tree by degrees shorter and shorter, until it be all consumed, for it burns night and day.”

At the time of the making of the English working class shoemakers were the most numerous artisanal craft. We’ll see that they provided John Lilburne with his revolutionary impetus. So here’s the Algonquin shoe. “They make shoes of moose skins, which is the principal leather used to that purpose; and for want of such leather (which is the strongest) they make shoes of deer skins, as they dress bare, they make stockings that comes within their shoes, like a stirrup stocking, and is fastened above at their belt, which is about their middle.”

“They love not to be cumbered with many utensils, and although every proprietor knows his own, yet all things (so long as they will last), are used in common amongst them: a biscuit cake given to one, that one breaks it equally into so many parts as there are persons in his company, and distributes it. Plato’s commonwealth is so much practiced by these people.” (Except that Plato’s republic excluded the poet.) The encounter makes Morton think. “If our beggars of England should, with so much ease as they, furnish themselves with food at all seasons, there would not be so many starved in the streets, neither would so many jails be stuffed, or gallows furnished with poor wretches, as I have seen them.” Morton grasps X cubed whose operation depends exactly on stuffed jails and wretches swinging in the wind, that is, mass incarceration and capital punishment.

In 1637 Harvard College was founded, and the first slave ship from Massachusetts launched its criminal expedition. Seven thousand English Bibles were printed in Amsterdam. They campaigned to capture Connecticut, and the lucrative fur trade, against Pequot control of exchange of pelts and wampum and European trade goods. William Bradford, the first governor of Massachusetts, said of the indigenous, “they die like rotten sheep.” Then he takes the land it “being the Lord’s waste.” Six or seven hundred Pequots were slaughtered one morning in May. In that same month of May the antinomians of Massachusets were defeated. Soon Anne Hutchinson would be tried and begin her exile. Governor Wm. Bradford of Plymouth, “It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire, and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stink and scent thereof.” Fort Mystic massacre. They were burned alive in “a flaming funeral pyre,” writes its historian, Al Cave.

Who? Whom? The Puritans decapitated the Hydra.

Freeborn John, Abolitionist

John Lilburne belonged to the radical publishing underground. He also was in Amsterdam at the time. The history and significance of the English Revolution could not be told without him. As a founder of the Levellers he was a leading head of the Hydra. Moreover neither he nor them can be understood without May Day.

He was arrested in England at the end of 1637 and brought to the terrifying court of the Star Chamber. “The Lord according to his promise was pleased to be present with me by his special assistance, that I was enabled without any dauntedness of spirit, to speak unto that great and noble assembly, as though they had been but my equals.” The attorney general and the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, tried to examine him but he refused to take the oath on the grounds that any answer he gave might incriminate him. There was no 5th amendment at the time. His refusal, in fact, is the origin of that constitutional right. For his refusal Archbishop Laud made him suffer – five hundred lashes delivered on his bare back at the cart’s tale two miles across London, hours pinioned in the pillory in Westminster, and then assigned to the Fleet prison where the keeper was instructed to keep him “close” (solitary), to shackle his legs in irons, to deny him medical attention, to prevent visitors, and not to feed him. He was kept in a cell where he could not stand up. Only a fire in the prison led to the alleviation of his conditions.

Yet, communication had been established thanks to a support network bravely and resourcefully knit together in which women were prominent. Pamphlets soon appeared – Work of the Beast (1638), Come out of her, my People (1639), The Christian Man’s Trial (1641) – and these were scattered about Moorfields among London’s excitable apprentices or helter-skelter in London’s streets. The seed of a new force was generated, a London crowd, that will operate as one of the contending forces along with King, Army, and Parliament during the English revolution.

The May Day riot of apprentices and sailors against the domicile of the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, in Lambeth Palace across the river Thames from the Houses of Parliament. Here the exclusive purveyor of ideology sought to control press, books, schools, and assemblies. Uniform, “thorough,” totally a state operation, everything on high, the established religion was such that you could not speak in church, only pray. And pay.

Who? Whom? Lilburne versus Laud.

In 1639 John Lilburne listened to Samuel How preach, a shoemaker, and had an awakening, an enlightenment that set him squarely on a revolutionary path with prisoners, sailors, and apprentices. “Make your selves equal to them of the lower sort,” the cobbler advised. These folks listened to scriptures like Bob Dylan listened to Woody Guthrie – listened, spoke, wrote, and sang. They absorbed and were transformed. The scripture that the cobbler expounded upon was from Paul’s letter to the Corinthians (1 Corinthians 1:27-28): “And he hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise, and God has chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty, and base things of the world, and things which are despised hath God chosen, yea, things which are not to bring to nought things that are.” In this Biblical culture this particular passage will be quoted or cited or paraphrased by Levellers, Diggers, and Ranters. It is easy to see why: it prophecizes the end of the existing order and it opens the question of class agency and class composition.

With the beginning of hostilities in the civil war between Charles I and Parliament Lilburne joined the Parliamentary army, saw combat, was wounded, and damaged his eye. One of his fellow soldiers, Thomas St Nicolas, was a poet, lawyer, and parliamentarian. In early May 1643 he was imprisoned in Ponetefract Castle by the Royalist army along with other common Puritan soldiers.

To see poor men stripped to their shirts and driven

Ten miles or twelve barefoot, some six or seven

Tied by the thumbs together, some, that stood

With shirts like boards stiffened with cold gore blood

Surbate and lamed i’the feet with walking bareThey were forbidden from praying collectively, they were packed tight together, friends and relations were forbidden to bring even “sorry rags t’the grate” or a bowl of milk; instead they sang psalms including Psalm 142 (“Set me free from my prison”) and Psalm 137 (“By the river of Babylon we sat down and wept”). Despite “close” conditions of deprivation and sickness, he woke after a long night,

And yet next morn to hear these caged birds sing,

To hear what peals of psalms they forth did ring,

To see their spirits not yet by these brought under,

Made their poor friends rejoice, their foes to wonder;

Would make a neuter in the cause believe

These men have somewhat whereupon to live,

Somewhat within when all without is gone,

The cause they fought for sure is right or none.He makes us realize that in addition to the dialectic of Who? Whom? There is another dialectic between “within” and “without,” or subjectivity and objectivity. They knew what they fought for, loved what they knew, and sang about it.

Prison abolition became part of the Leveller program. Small wonder, since that’s where they spent so much time. Free-born John was locked up or exiled for most of the Revolution, victimized by the Bishops, by Star Chamber, by the House of Lords, by the House of Commons, and finally by Oliver Cromwell. These were the institutions of the grandees who thought “men’s merits are measured by the aker, weighed by the pound.” Prison experience could be hard time too, in solitary or “close” confinement, legs shackled in irons, without medical care to his wounds, denied visitors, putrid water, lousy rags, crumbs for food if anything. He petitioned Parliament over and over again but found his most trusted allies among sailors, ‘prentices, and poor old women. “I resolved,” he wrote in 1647, ” … to make my complaint to the Commons of England, and to see what … the Hobnayles, and the clouted Shooes will do for me.” He referred to the footwear of people who walked on the soil and through the mud and muck of horse traffic. These were the “commons.” He feared for his life in prison, and indeed one of his guards had formerly been the executioner, the hangman. He appealed directly to London’s apprentices. “Wherefore unto all you stout and valiant Prentizes, I cry out murther, murther, murther, murther ….”

William Walwyn was a polished ironist and subtle critic with a plausible pen. He was a man of means and Lilburne’s adroit and influential comrade who wrote pamphlets, organized defense of his imprisoned friend calling meetings, appointing committees, drafting petitions, getting them printed, paid for, circulated, and delivered with a noisy throng to the door of the House of Commons. What C.L.R. James will call the first political party with particular view to franchise. We have to add that this movement grew in relation to the imprisonment of its leaders. It’s not just that Lilburne’s expressed views were those of a prison abolitionist; his prison experiences triggered an explosive insurrectionary revolutionary movement.

In 1648 he wrote at least four pamphlets comprising, his biographer says, a comprehensive condemnation of the prison system. They were The Prisoner’s Mournful Cry, The Prisoner’s Plea for a Habeas Corpus, The Lawes Funerall, and England’s Weeping Spectacle. His August 1646 pamphlet Liberty vindicated against Slavery indicted the prison system as you can tell from its subtitle, Shewing that imprisonment for debt, refusing to answer interrogatories, long imprisonment though for just causes, abuse of prisoners, cruel extortion of prison keepers, are all destructive to the fundamental laws and common freedoms of the people. To the Levellers slavery and prison were overlapping structures of oppression. They were abolitionists. The campaign in 1646 to free him from imprisonment in the Tower spawned the Leveller party and led to An Agreement of the People for a firm and present peace upon grounds of Common Right.

From Newgate prison he wrote Liberty Vindicated Against Slavery (1646). “But alas we have but the shadow of it [liberty], we by the subtilty of Lawyers, are only free men in name, the English man’s freedom is now become worse than the Turkish slavery, how many of us lye and languish in your murthering prisons to the provoking of the God of Justice unto wrath against you) & our wives & children thereby exposed to all want & misery; whose loud cries and tears (doubtless) will draw down vengeance from the just hand of Heaven upon you (if not speedily prevented by administration of justice.)”

They drafted and argued for the Agreement amidst the soldiers (October 1647), and revised, and argued for it again before Parliament (Dec. 1648), and a third time revised and published from imprisonment in the Tower of London, An Agreement of the People, this time on May Day 1649. This was the first democratic constitution. It is the precedent to the Constitution of the U.S.A. but better. The U.S.A. constitution had to be quickly amended with the Bill of Rights. It used to be well-known and Supreme Court judge, Hugo Black made clear in his dissenting opinion to Adamson v. California, 332 U.S. 46 (1947), that the first eight amendments owe their origins to the defenses that Free-born John Lilburne created in his trials during the English Revolution. The right to face your accuser, the right to hear the accusation, the right to refrain from self-incrimination, the right to counsel are some of the rights originating in Lilburne’s tenacious creativity in the teeth of the autocratic court. Equality before the law, religious toleration, manhood suffrage, abolition of debtors prison, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, for these too he fought and suffered and in time, seven generations down the line, were won (it seemed).

That May Day Agreement of the People shall be a caution, a warning, and a challenge to readers in 2023. It came from prison! It came on May Day! The attack on Archbishop Laud’s Lambeth Palace which we illustrated in the Hydra. The ‘prentices and sailors are the artisans or crafts people who will be devalued as the division of labor extolled by Adam Smith grows apace, and they are the sailors of a global proletariat of the mercantilist imperial state. The May Day 2023 themes are class composition, incarceration, and social constitution. Who will bring to nought the things that are? M’aidez! M’aidez!

Pauline Gregg asked of the Leveller programs, “What was there … to appeal to the landless labourer or to the industrial wage-earner?” She continued, “If the Levellers instead of repudiating, had entered into alliance with the dispossessed, represented by the Diggers, would the issue have been any different?” Winstanley believed that Parliament’s declaration of a free commonwealth authorized the sort of communist society which the Diggers wished to see established.

Levellers and Diggers did not join. The 30th article in the Agreement of the People made the reason plain: “That it shall not be in the power of any representative, in any wise to … to level men’s Estates, destroy Propriety, or make all things Common.” No sooner said than challenged. An anonymous comrade combined the words for tyranny and hypocrisy to make “tyrannipocrit” and wrote, “All you who have cast out any old tyrants, consider seriously what you have yet to do, and so near as you can make and maintain an equality of all goods and lands; …. Which if you will not perform, you are worse than the old tyrants, because you did pretend to a bettering, which they did not.”

In January 1649 Charles I was decapitated. In April 1649 Gerrard Winstanley and the Diggzers began to dig. On May Day the Leveller collective imprisoned in the Tower of London published the Agreement of the People.

We want another “world.” Another is possible. The world of soul, of spirit, of life, something as of yet unheard of, at once necessary and kind. The Levellers and the True Levellers, the imprisoned Lilburne, the digging Winstanley, can help. Four years later on May Day 1649 the Levellers imprisoned in the Tower published The Agreement of the People. It needs remembering because American revolutionaries need to put into words how we intend to constitute ourselves, separate “identities” notwithstanding, in common and with commons. Land Back and Reparations.

The Agreement of the People concludes, “Thus, as becometh a free People, thankful … for this blessed opportunity, and desirous to make use thereof … in taking off every yoke, and removing every burden, in delivering the captive, and setting the oppressed free; we have in all the particular Heads [headings] forementioned, done as we would be done unto…”

John Lilburne cried from his prison cell in 1648. “Wherefore unto all you stout and valiant Prentizes [apprentices] I cry out murther, murther, murther, murther.” On May Day 1649 his prison collective published An Agreement of the People, the first democratic constitution. Free-born John Lilburne was a dedicated life-long abolitionist who opposed slavery and prison with equal fervor. As a young man ten years earlier he had to elude anonymous assassins in prison, now with the defeat of his party in 1650, he found it necessary again to call for help in prison conditions of darkness and bad air where murder lay easily in the shadows.

John Lilburne appealed to the commons. By this he did not mean House of Commons whose members were measured by “the aker and weighed by the pound.” By commons he referred to the common people, particularly to “hobnayles and clouted shoon.” Clouts were cleats, squared headed nails hammered to the sole, either or together they provided a grip to the mud, muck, and mire for all those who walked the ground or worked the earth. They were not footwear for nobles who rode horses. They were class signifiers.

Who? Whom? The acres and pounds versus hobnayles and clouted shoon.

Since the end of the 14th century the commonalty of people imagined the body politic in their own vernacular: I quote David Rollison. “The head is the king. The neck holds up the head and is a just judge, the pillar of justice. The breast fills the body with life-giving breath, allowing good spirits in and keeping bad spirits out, just like a good priest. Lords are shoulders and backbone; arms are knights. ‘Yeomen’ are fingers. They grasp and control the earth and the commonalty that works it. Lawyers are ribs to protect the heart, thighs are merchants ‘that bear the body’ and maintain boroughs and cities … and good households of great plenty.’ Artisans are the legs, ‘for all the body they bear, as a tree bears branches’. The feet are ‘all honest [trewe] tillagers of the lands [with] plough and all that dig the earth. All the world stands on them.’ The toes are faithful servants, without which the tillagers themselves ‘may not stand.’ Yet toes, feet, and legs do not speak.”

Analysis of class forces during the English revolution included the cavaliers (established church and king), the roundheads (merchants and masters), and finally the many-headed Hydra including the “hobnayles and clouted shoon” who have been historically mute. This was changing from quiet murmuring to Lilburne’s shout. Even the written historical archive allows us to see that by the 1640s everything had changed. The enclosure of land, the loss of the commons began its steady two century progress, Parliamentary enclosure act by Parliamentary enclosure act until England itself was closed.

If we do not hear the tongue of silent common people during the 1640s, we can at least read their words including those by the most prolific pamphleteering prisoner the world had yet known. The importance of the “toes” of England must include Elizabeth Dewell who became the wife of Freeborn John, Elizabeth Lilburne. She served him well bringing food and raiment to prison, smuggling out his manuscripts, eluding the censors, finding surreptitious printing presses unknown to the pursuivants of power, petitioning the powerful in court or Parliament. Women made life possible for Free-born John, in and out of prison. She saved his life on numerous occasions interposing her body when he was attacked by guards, all the while trying to preserve the lives of all their children. Mary, Overton’s wife, similarly was his life-line in Newgate and the Tower. Yet massive repression was directed against women at the time. Much of this occurred at the same time that the Witchfinder General, as Matthew Hopkins termed himself, was hanging sixteen women and two men as witches in Bury St. Edmunds in 27 August 1645. Two weeks earlier Lilburne was committed to Newgate. 1645 was the year when the Leveller party emerged with the publication of Lilburne’s Englands Birth-right Justified.

Through his life Freeborn John paid close attention to the feet. It was the preaching in 1639 of Samuel How, a cobbler, which led to Lilburne’s momentous spiritual and political insight that turned the world upside down. It was another shoemaker, Luke Howard, who visited him in 1653 in the dungeon of Dover castle and convinced him in the outer darkness of historical defeat to rely on an inner light. Lilburne’s spiritual life was grounded in a literal sense. After the victorious battle of Naseby (164) he petitioned Parliament to provide the soldiers with shoes and socks. It was reported that a bootmaker refused to size him for a new pair of riding boots in the belief that he had not length of life left to wear them. Shoes were needed for locomotion, locomotion is the basis of human freedom, hence the African-American spiritual with its who? whom?:

I got shoes, you got shoes,

All God’s children got shoes.

When I get to Heaven gonna put on my shoes,

Gonna walk all over God’s Heav’n, Heav’n, Heav’n,

Everybody talkin’ ‘bout Heav’n ain’t goin’ thereThe Levellers did not speak for them all. Diggers, or true levellers, were closer to the ground than Levellers who organized only in opposition to authority in state or church. The Diggers attempted to by-pass them, going straight to the goods, the earth. What Diggers and Levellers have in common is the commons but this term had different meanings to them. To Levellers the commons are the people. To Diggers commons may refer to lakes, land, shore, rivers, other relations. The concept of the “nation” is to mix up the people and the land; it’s imaginary precisely because it is without the commons in either sense of the term. History from below gives the toes, feet, and legs leave to speak.

Thomas Morton tells how the Algonquin people of Massachusetts shared utensils and cake, the commons of consumption we might say. To Gerrard Winstanley the whole earth was a common treasury, the very ground and land. “Work together, break bread together,” he said. A commons of production we could add. John Lilburne saw the hobnayles and clouted shoes, the free-born people, as the commons, the commons of ‘we the people.’ Opposed to them were the settler colonists enclosing by conquest, the King and gentry enclosing by command, and the Parliament enclosing by statute. Who? Whom? Ian Angus tells the story in The War Against the Commons.

On May Day 2023 we look back to the intersectionality of the first Maypole in Turtle Island. On May Day 2023 we can look back to the primacy of the people and fellow creatures or relations of the species of the woods, fields, rivers, air, and seas. We’ll also find that our Bill of Rights, our struggle for universal adult franchise, the demand for an equality of the delights, comforts, and joys of life – they might call it the common wealth, all this bears a direct relation to the historical forces brought together by that first May Day on Turtle Island, Passonagessit to be precise. They can’t be attained without the red side of May Day, that is the class struggle, and agreements of the people.

Therefore from this part of the world, the Great Lakes, we call for solidarity with the women of the Giniw collective protecting our waters. We call for solidarity with the graduate students on strike at the University conveying knowledge to the next generation. We call for solidarity with the opponents of Cop City in Atlanta, Georgia, and the preservation of the forest that it threatens. We call for solidarity with the incarcerated in penitentiary, prison, and jail. On May Day we connect the dots.

Thanks to Michaela Brennan, Tim Healey, Joe Summers, Janie Paul, and all my friends at Retort, ECI, and Under the Bus. ↑

Some References

Ian Angus, The War Against the Commons: Dispossession and Resistance in the Making of Capitalism (Monthly Review Press, 2023).

Anon, Tyranipocrit Discovered (Rotterdam, 1649)

William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (many editions)

Alfred A. Cave, The Pequot War (Amherst, Mass.: 1996)

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch (Autonomedia, 2004)

Pauline Gregg, Free-born John: A Biography of John Lilburne (London, 1961)

Tim Healey, The Green Man in Oxfordshire (2022)

Christopher Hill, The World Turned Upside Down (1972)

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants (Milkweed, 2013)

Peter Linebaugh, The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day (PM Press, 2016)

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, The Many-Headed Hydra (Beacon Press, 2000)

Thomas Morton, The New English Canaan (Amsterdam, 1637)

Thomas St. Nicholas, For My Son (1643)

Janie Paul, Making Art in Prison: Survival and Resistance (Hat & Beard, 2023)

John Rees, The Leveller Revolution: Radical Political Organization in England, 1640-1650 (Verso, 2016)

David Rollison, A Commonwealth of the People: Popular Politics and England’s Long Revolution, 1066-1649 (Cambridge, 2010)

Franklin Rosemont and David Roediger (eds.), Haymarket Scrapbook (Chicago AK Press, 2012)

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News