Summary

Russia’s war on Ukraine has shown European citizens that they live in a world of non-cooperation. But their cooperative foreign policy instincts are only slowly adapting to this new reality.

Europeans want to remain neutral in a potential US-China conflict and are reluctant to de-risk from China – even if they recognise the dangers of its economic presence in Europe. However, if China decided to deliver weapons to Russia, that would be a red line for much of the European public.

Europeans remain united on their current approach to Russia – though they disagree about Europe’s future Russia policy.

They have embraced Europe’s closer relationship with the US, but they want to rely less on American security guarantees.

European leaders have an opportunity to build public consensus around Europe’s approach to China, the US, and Russia. But they need to understand what motivates the public and communicate clearly about the future.Introduction

In the years to come, the European Union will likely face difficult strategic decisions: whether to back the United States in its geopolitical competition with China; whether to punish China for its support of Russia; whether to rebuild relations with Russia after the war.

These decisions will affect European citizens – whose support European leaders will need for their foreign policy choices. Two years ago, the European Council on Foreign Relations conducted a study of public opinion about how Europeans see their place in the world. The results pointed to a cooperative European mindset whereby, in a world of competing great powers, Europeans preferred to cultivate strategic partnerships with various countries and advocated a largely values-based foreign policy.

Since then, Russia’s revisionism, the rising danger of a military confrontation between China and the US, and the disruption of global supply chains first by the covid-19 pandemic and then Russia’s war on Ukraine, have called this cooperative mindset into question. In response to these developments, European leaders have expediated their plans to strengthen Europe’s role in the world. But there is major disagreement on the substance and purpose of this role. For example, should the EU aim to become an autonomous ‘third pole’ alongside the US and China or concentrate on strengthening the transatlantic alliance? Should it find its own way of dealing with China, independent of the US, or should it strive for a joint transatlantic China policy? Should it aim to cut all ties with Russia in the future, or should it envisage some form of cooperation after the war?

The strategic direction of European foreign policy will have a massive impact on the lives of every European citizen – be it through their exposure to security threats, supply chain disruptions, or the volatility of the financial market. Their opinions will enable or constrain European leaders’ ability to negotiate a common European foreign policy. As these leaders re-adjust their relationships with the US, China, and Russia, they not only need to reach agreement among themselves – they also need to build a public consensus around European foreign policy. Otherwise, there is likely to be growing mistrust of the elites and the EU, and a populist backlash in the European parliamentary election in 2024 and in national elections.

In April 2023, ECFR conducted an opinion poll across 11 EU member states – Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Sweden – to understand how European citizens see their place in the world today. The results of the poll show that their cooperative foreign policy instincts are adapting slowly to the new geopolitical reality that is characterised by growing polarisation. European citizens aspire to remain neutral in a US-China conflict and are reluctant to de-risk from China – even if they recognise some risks in China’s economic presence in Europe. They are increasingly pleased with their relationship with the US – though they recognise that it might not be sustainable. Finally, they remain united on the war in Ukraine – but for now have different opinions on the type of relationship Europe should have with Russia after the war.

This paper analyses what European citizens currently think about Europe’s place in the world and its relationship to other powers, and whether the main divisions on these issues occur between member states, within member states, or between citizens and their governments. It also provides guidance for European leaders on how to best take public opinion on board when deciding how to translate the idea of a sovereign Europe into practice.

“China is not Russia”

In November 2022, shortly after Xi Jinping had secured his third term as the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Germany’s chancellor, Olaf Scholz, paid his respects to the Chinese leader with a state visit. Since then, various European leaders have made their way to Beijing: from European Council president, Charles Michel, to Spain’s prime minister, Pedro Sanchez, to the joint visit by the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, and French president Emmanuel Macron in April 2023. But these trips have not signalled European unity on China. To the contrary, European governments hold different views about Europe’s approach to China, with von der Leyen and Macron at opposite ends of the spectrum.

In a keynote speech in March 2023, von der Leyen used unusually strong words to describe China’s strategic priorities. In her view, Beijing is striving for security and control instead of reform and opening, and is aiming to systemically change the international order, making China less dependent on the world and the world more dependent on China. Von der Leyen dispensed with the EU’s established triad to describe China as a “partner, competitor, and systemic rival” and emphasised the need for active, strategic, multidimensional risk minimisation in Europe’s dealings with Beijing. With this strategy of “de-risking”, she pushed for a new consensus in Europe on the importance of revisiting its relationship with China.

For his part, Macron struck a much more conciliatory tone in Beijing, advocating greater rapprochement after three years of China’s rigorous “zero covid” restrictions. Contrary to von der Leyen’s de-risking approach, Macron spoke of reviving the strategic and global partnership with China and deliberately avoided critical remarks on the subject of Taiwan. Like Scholz before him, Macron was accompanied by a business delegation, which concluded numerous agreements in China. Macron’s message to Xi was clear: Paris wants close economic relations with Beijing, even if China does not oppose Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and continues to maintain close relations with the Kremlin. In fact, Macron has often suggested that the EU should work with China to solve the Russia problem.

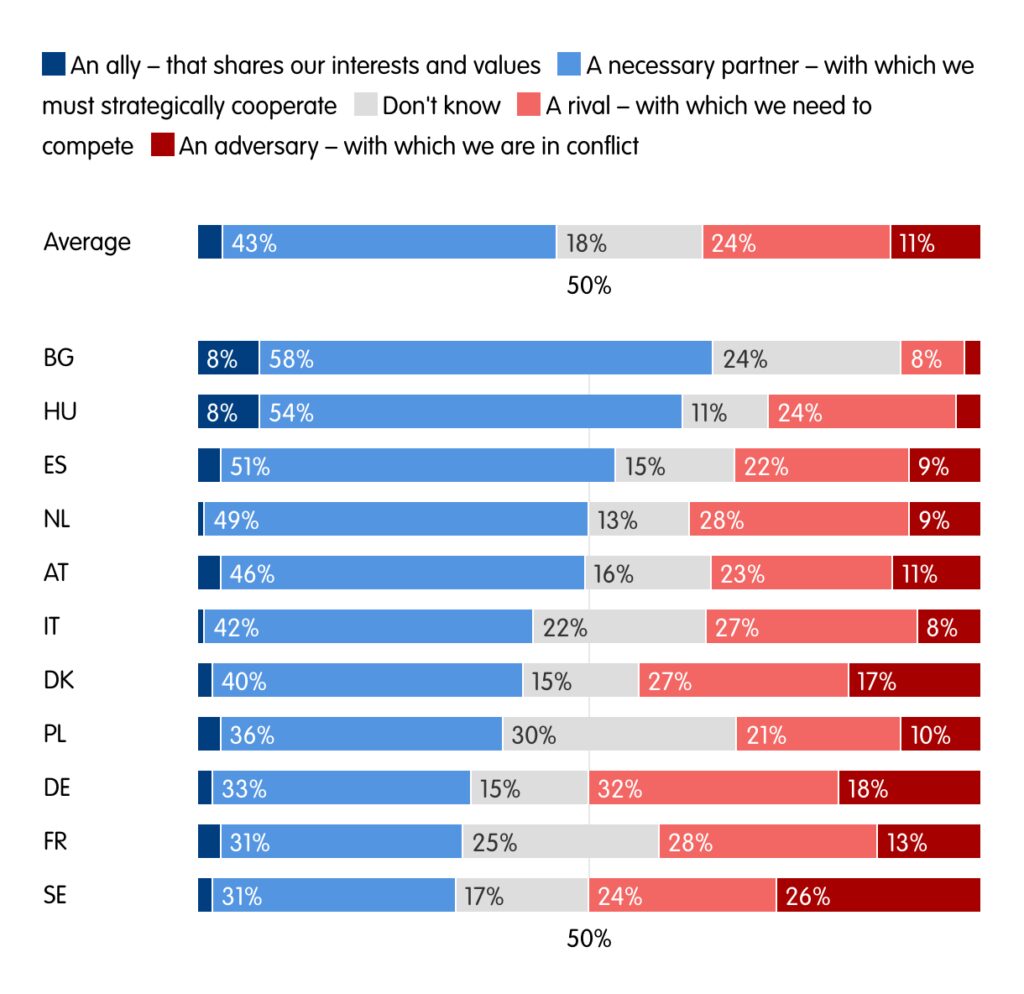

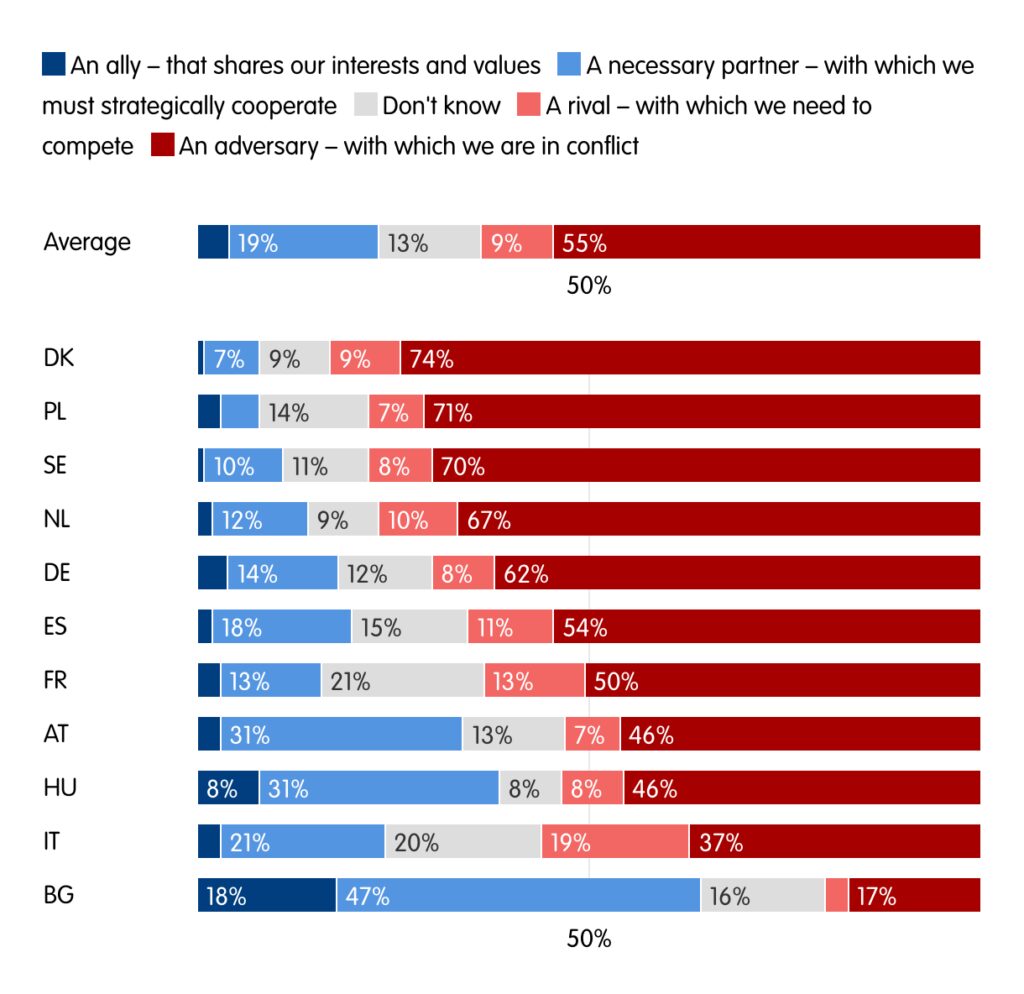

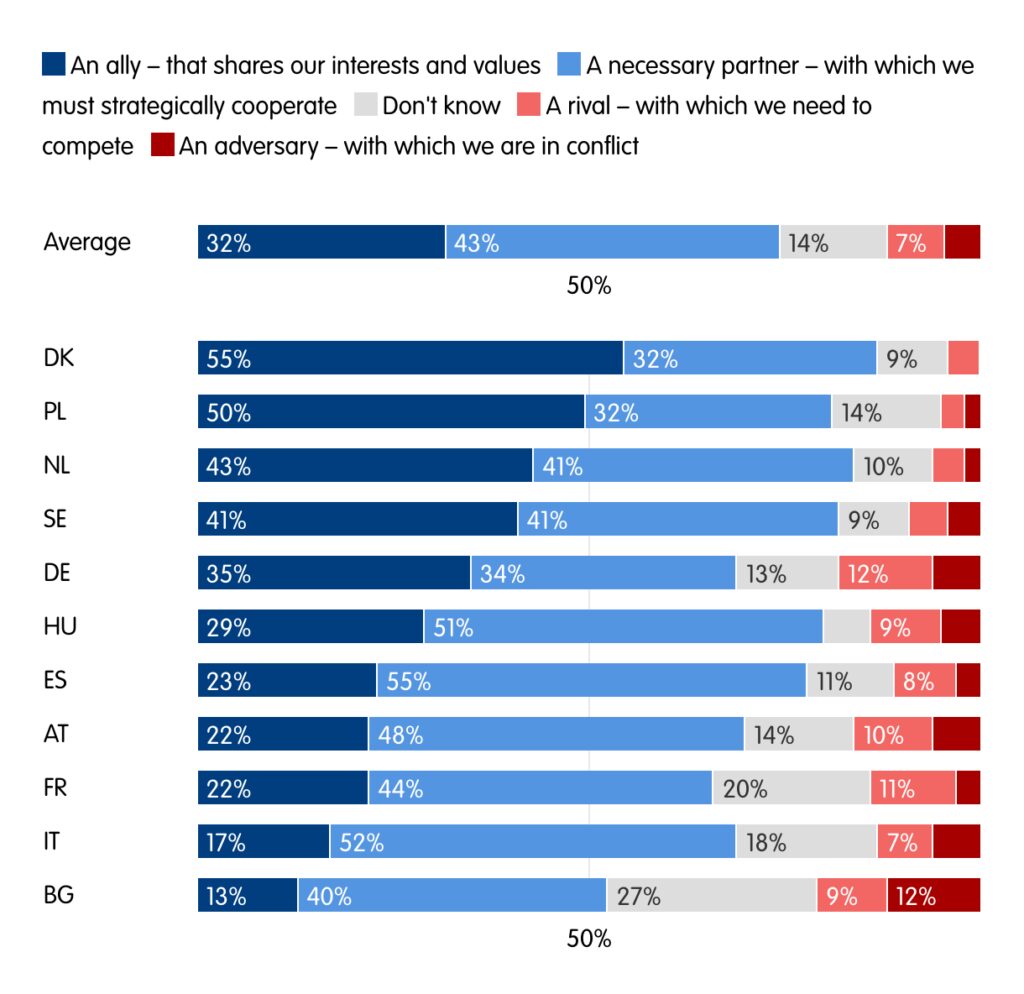

The findings of ECFR’s latest poll show that, in many ways, European citizens are more on Team Macron than Team von der Leyen. They do not see China as a power that challenges and wants to undermine Europe, and they do not buy into the “democracy versus autocracy” framework promoted by the Biden administration. Despite the “no limits” partnership that China and Russia announced in February 2022 and Beijing’s subsequent refusal to condemn Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the poll results show that Europeans’ perception of China has changed surprisingly little when compared with the results of the poll conducted in 2021. Now, the prevailing view in almost every country in which we polled is that China is Europe’s, and the respective country’s, “necessary partner”.

Germany, Sweden, France, and Denmark are the only countries where the prevailing view is to see China as a “rival” or an “adversary”, rather than an “ally” or “partner”. But this was also the case in 2021. Paradoxically, von der Leyen’s call to de-risk Europe’s relations with China finds sympathetic audiences in the two countries – France and Germany – whose leaders have, so far, promoted a considerably more obliging approach.

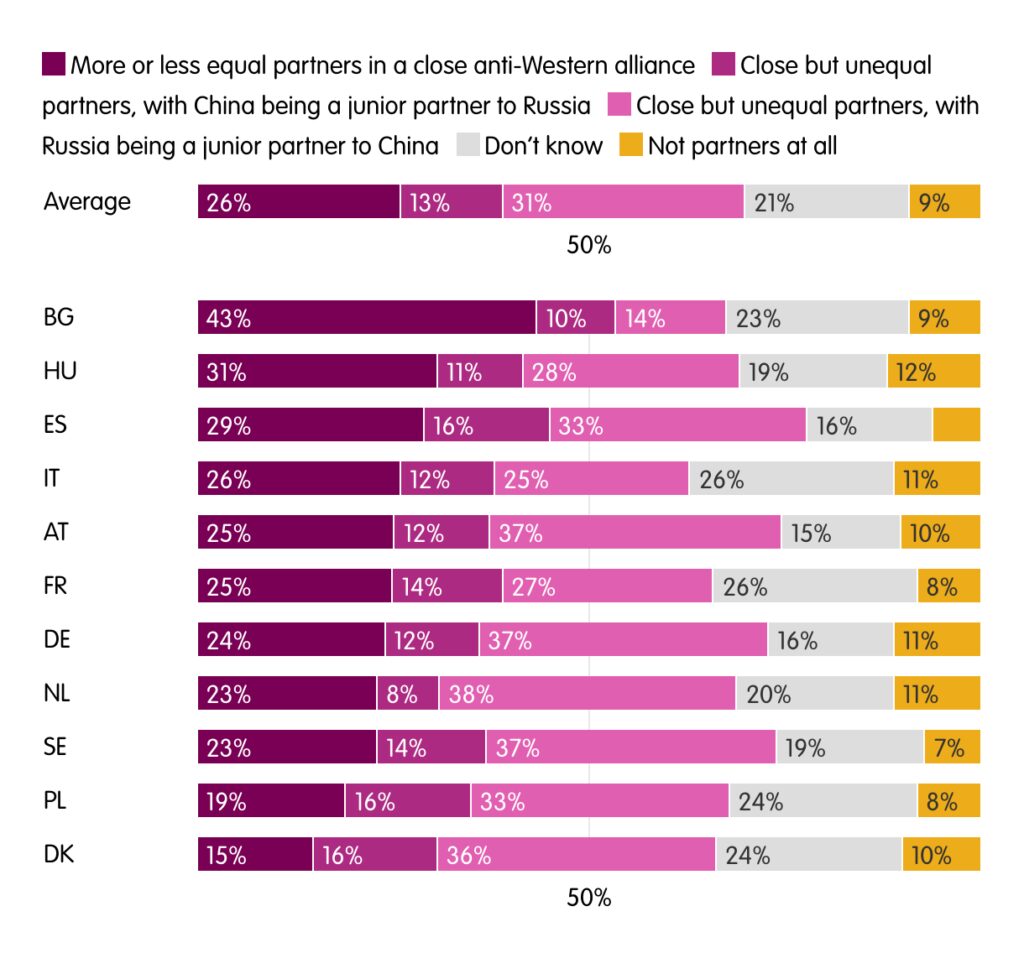

Europeans have no doubt that Russia and China are working together on the global scene. On average, 70 per cent of respondents recognise the two as close partners.

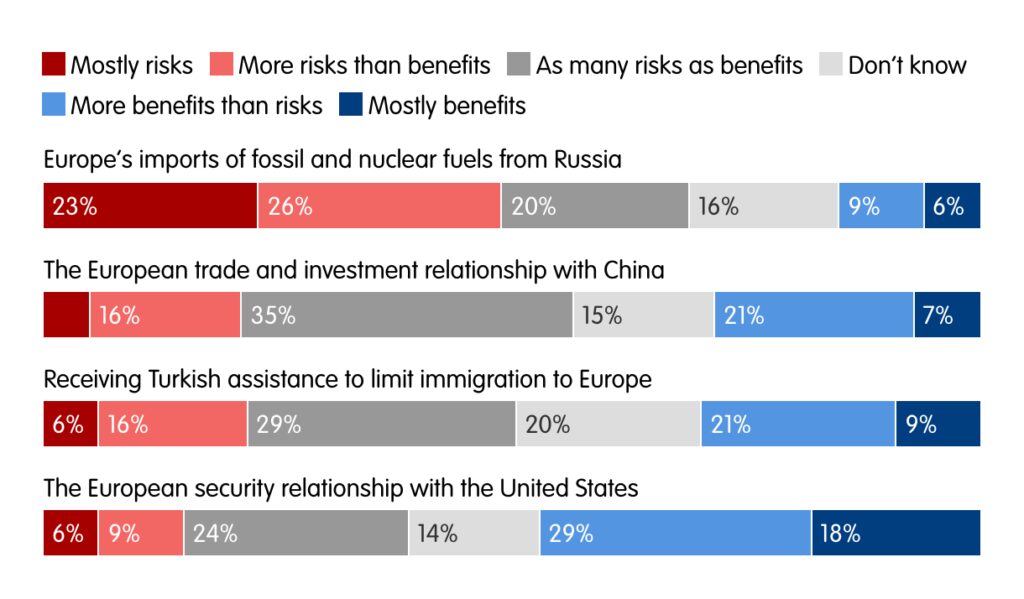

But that does not lead them to conclude that Europe should decouple from China as it has from Russia. Across the countries surveyed, on average only 22 per cent of Europeans consider the region’s economic relationship with China as bearing more risks than benefits. Meanwhile, there is a much broader recognition of the risks entailed in importing energy fuels from Russia. This suggests that, for the public, the European Zeitenwende – to use the term that Scholz coined in his now famous speech in February 2022 – relates only to Russia, and not to China.

When thinking about China, Europeans do not appear to link it to Europe’s experience of its dependence on Russia and the resulting energy crisis in Europe. The prevailing view in almost every country included in our survey is that the risks and benefits of Europe’s trade and investment relationship with China are balanced; Bulgarians even consider the benefits to outweigh the risks. In no country did most respondents consider Europe’s trade with China to entail more risks than benefits.

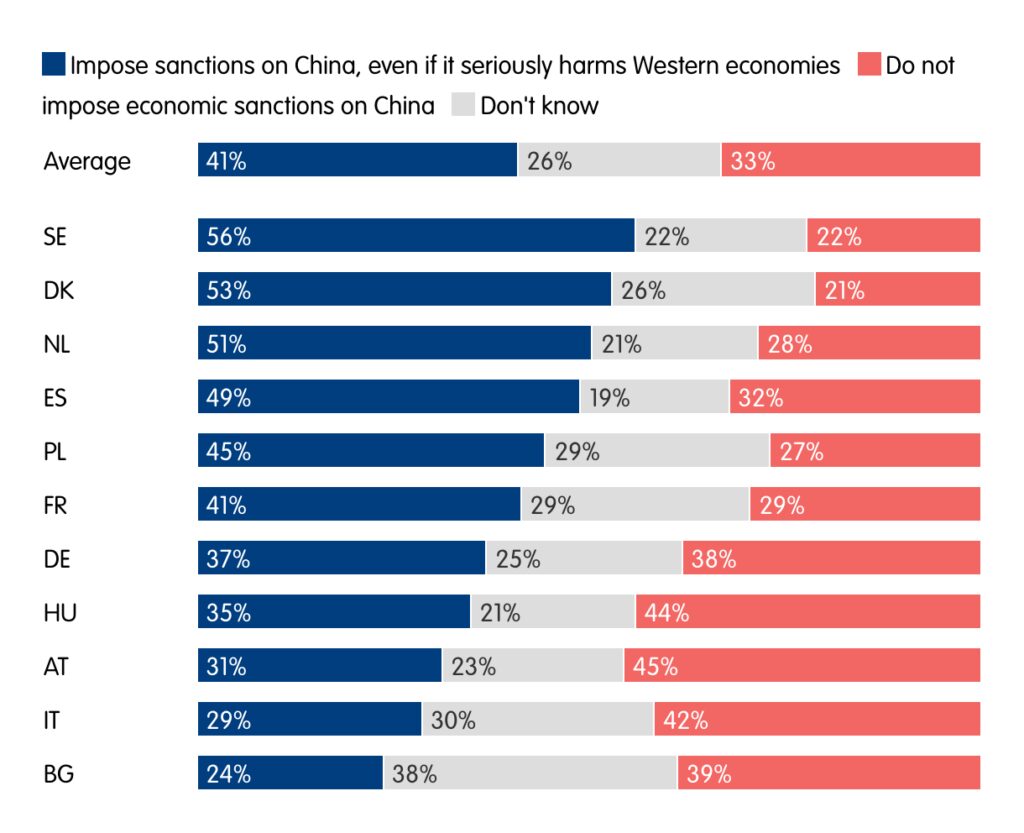

However, if Beijing decided to deliver ammunition and weapons to Russia, many Europeans would consider this a red line. On average, 41 per cent would be ready to sanction Beijing in that event, even if that meant seriously damaging Western economies. A minority of 33 per cent, on average, would oppose this.

Still, European countries are far from united on this. According to the results of our survey, only in Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands would an absolute majority be in favour of such sanctions. Meanwhile, in Austria, Hungary, Italy, and Bulgaria, there is a clear preference against such a move – constituting a major constraint on governments. Some practical reasons may explain this. The Swedish and Danish economies rely much less on trade with China than those of Italy and Germany, making sanctions less costly for the former. At the same time, Italian and Bulgarian households are more economically vulnerable than those of northern Europe. But even there, at least a quarter of the public would be in favour of potentially costly sanctions.

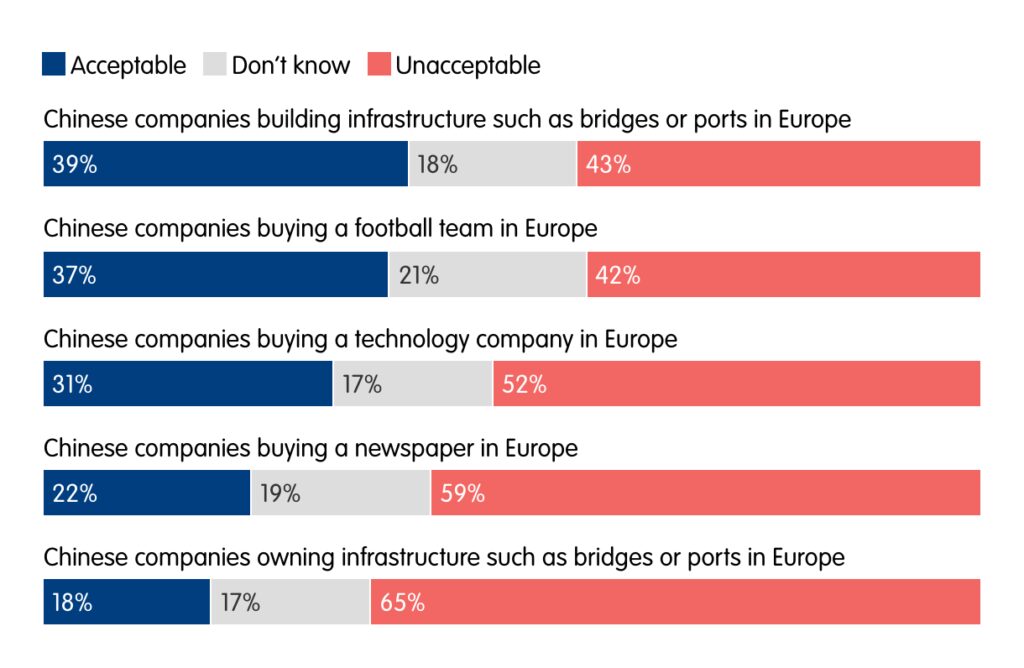

Moreover, Europeans display considerable caution about the practical aspects of China’s economic presence in Europe, for example, whether Chinese companies should be allowed to build and own infrastructure in Europe or buy newspapers, technology companies, and football clubs. On average, a majority would oppose allowing Chinese companies to own infrastructure in Europe, as well as to buy a European newspaper or technology company. We asked the same question in late 2020 and, since then, Europeans have grown somewhat more concerned about China’s economic presence in Europe – especially in Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Hungary. Currently, the three countries in which the population is most opposed to China’s economic presence are Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands – while Bulgaria and Spain are the most open to it.

When it comes to the potential risks of economic interdependence with China, European citizens focus more on China’s concrete economic presence in Europe than on Europe’s more abstract and distant trade and investment links with China – for example European companies relying on China for much of their supply chains – and the threats these could pose for Europe’s strategic sovereignty. This may be partly because, for the moment, Europe’s dependence on China has not been nearly as evident in the media or in people’s lives as its energy dependence on Russia since the latter’s invasion of Ukraine.

United on Russia

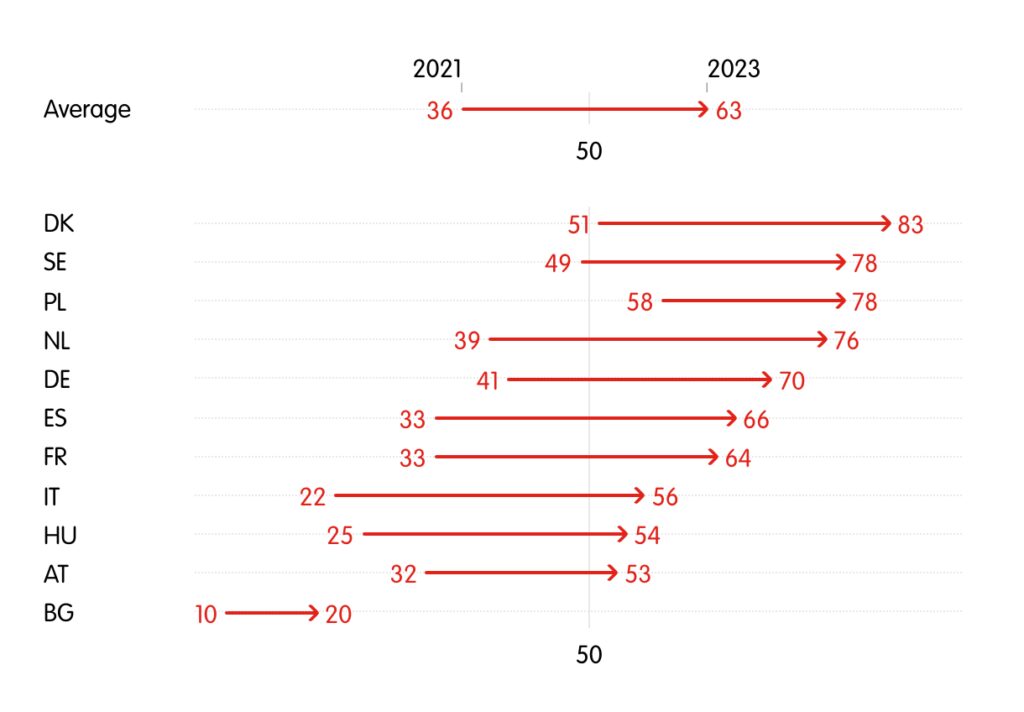

In contrast, Europe’s relationship with Russia has undergone a real Zeitenwende. With the exception of the Hungarian leadership, European governments have been strongly united in their support for Ukraine and their opposition to Russia. On this, their approach has usually been in sync with domestic public opinion. In most surveyed countries, a majority agrees that Russia is their country’s – and Europe’s – “adversary”. Out of the countries included in our survey, the populations of Poland, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany are the main hawks in this respect.

In most cases, the public’s views on Russia have changed significantly since our 2021 survey. On average, the share of respondents who see Russia as Europe’s “rival” or “adversary” has increased from around one-third to almost two-thirds; at the same time, sympathies towards Russia have dropped considerably. Among the surveyed countries, Bulgaria is the only one where the majority of the public continues to see Russia as Europe’s “ally” or “partner”, and where little has changed in that respect since 2021. (When asked about “their country’s” relationship with Russia, the majority in Hungary, as well as in Bulgaria, sees Russia as an “ally” or “partner”.) There is currently a clear mandate in Europe for a policy that seeks to establish European security not with Russia but against it.

Worryingly, Italy falls somewhere in between – with a quarter of respondents considering Russia Europe’s, or their country’s, “ally” or “partner”, and only about a third seeing it as an “adversary”. The Italian public’s ambiguity towards Russia may call into question the durability of the Italian government’s support for Ukraine. Other European capitals could fear Rome revisiting its stance under different conditions – for example, if Donald Trump is re-elected in the US, or if more governments across Europe become sceptical about the EU’s current strong stance against Russia. But, alongside the Netherlands, Italy is the country in which public perceptions of Russia have undergone the biggest change over the past two years. Italy has also successfully disentangled itself from its energy dependence on Russia; and – in contrast to Austria, Germany, or the Czech Republic – it has not witnessed major protests against EU sanctions on Russia.

Once the war is over, Europeans are likely to disagree on their long-term relations with Russia. While European leaders have not publicly discussed this issue in depth, some capitals have already signalled radically different approaches. Last year, Scholz said that economic relations between Germany and Russia could be resumed when Russia stops its aggression. Macron may consider a rapprochement too, given his pre-war efforts to include Moscow in Europe’s future security architecture and subsequent remarks about the need to show Russia more respect and to provide it with security guarantees. Meanwhile, Poland’s prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, has repeatedly criticised western Europe’s pre-war cooperation with Russia – and suggested that it must not make the same mistakes again. The Baltic countries have called for a similarly hawkish approach. For example, Estonia’s prime minister, Kaja Kallas, recently called Russia a “pariah state”, and said that there is “no room for flirting with the idea of resuming business as usual”.

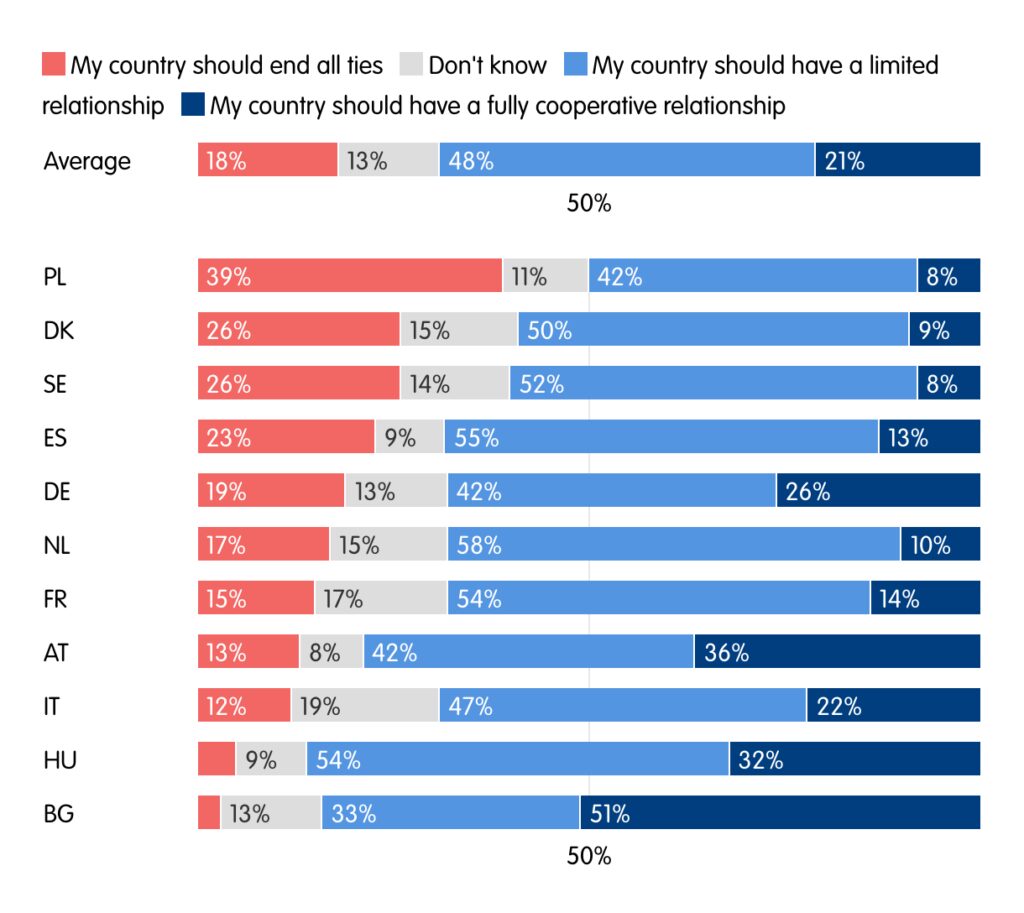

There is, however, less of a divide among the European public. In every country that we surveyed, 50 per cent or more would like their countries to re-establish at least some form of relations with Russia if the war ends in a negotiated peace. Almost everywhere, the prevailing view is that Europe should pursue a limited relationship with Russia, for example only trading in certain industries. Overall, this provides the foundation for an agreement among the European public when the moment comes to reset relations with Moscow.

Nonetheless, some controversy looks unavoidable. For example, in Poland, 39 per cent are willing to end all relations with Russia. Meanwhile, a majority in Bulgaria, about a third of Austrians and Hungarians, and a quarter of Germans are already considering re-establishing a fully cooperative relationship with Russia after the war. It would be dangerous if European discussions on this issue were driven by these extreme positions.

The return of the American ally

When we conducted our polling in spring 2021, Trump’s legacy and the images of the Capitol building being stormed by rioters were still deeply ingrained in the minds of the European public. While the need to strategically cooperate with the US was omnipresent in the results of our survey, no EU member state saw the US as predominantly an “ally” that “shares our [European] interests and values”. The sense of alliance was most pronounced in Poland and Denmark, but even there respondents predominantly perceived the US as a “necessary partner”. In Germany and Austria, minorities of over 20 per cent saw the US as a “rival” or an “adversary”.

Fast forward to 2023 and the picture is considerably different. The majority in Denmark and Poland say they consider the US as Europe’s “ally”, which is also a prominent view in the Netherlands, Sweden, and Germany. In Austria and Germany, those who perceive the US as an “adversary” now constitute a mere 6 per cent. Only in Bulgaria does more than 10 per cent of the population see the US as a foe.

Russia’s war on Ukraine has seen US leadership return to Europe – and it seems European leaders and publics alike have been more than happy to embrace it.

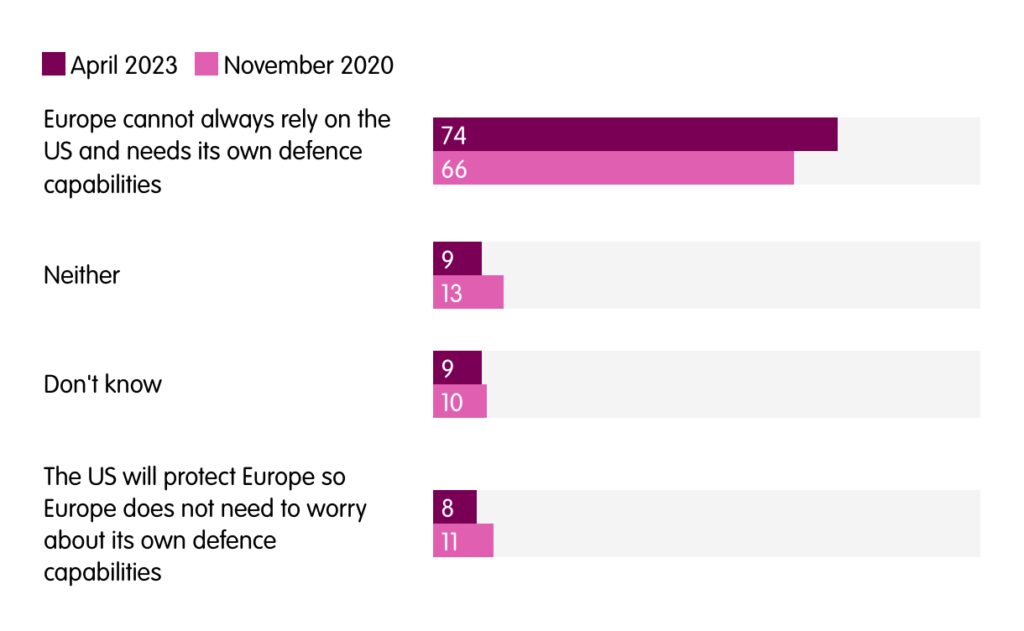

However, three-quarters of respondents agree that Europe cannot always rely on the US, and that it needs to look after its own defence capabilities – while less than a tenth believe that the US will always protect Europe, so Europeans do not need to worry as much about their own defence capabilities. This is an increase compared to a poll conducted in November 2020, despite the fact that back then, Trump was questioning the purpose of NATO and threatening to withdraw the US from the alliance. The increase has been particularly marked in Hungary, the Netherlands, and Germany.

Thus, Europeans do not see the Biden administration’s strong engagement in Ukraine as a reason to relax; on the contrary, they feel strongly that Europe needs to boost its capacity to act in the area of security and defence. These results should reassure all those politicians who are concerned that they will be unable to communicate additional expenditure for military capabilities – which now looks imminent – to the population. In March, NATO’s secretary-general, Jens Stoltenberg, urged member countries to speed up their increases in defence spending as only seven of the alliance’s 30 countries had met the current goal of spending 2 per cent of their GDP on defence in 2022.

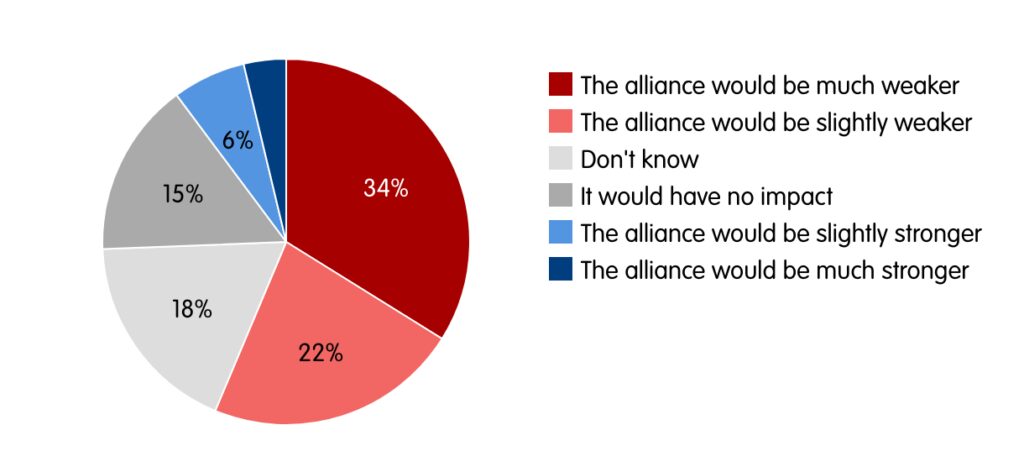

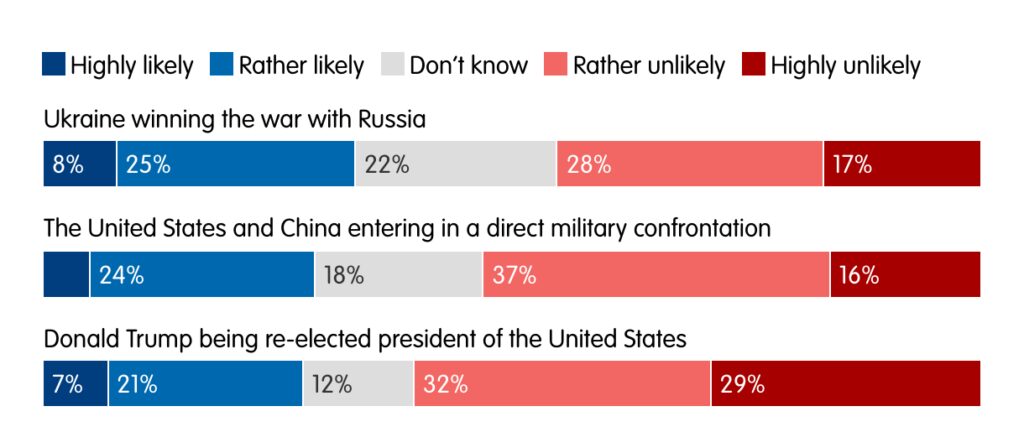

At the same time, Europeans do not see their reliance on the US for security as particularly dangerous. As shown above, on average 47 per cent consider this relationship to bear more benefits than risks – while only 15 per cent think the opposite. And while, on average, a majority agrees that the transatlantic alliance would be weaker in the case of Trump’s re-election, they usually consider this scenario to be unlikely. This suggests that, although they might be supportive of investing in European defence capabilities, they are not convinced of the need to do so urgently or as a high priority.

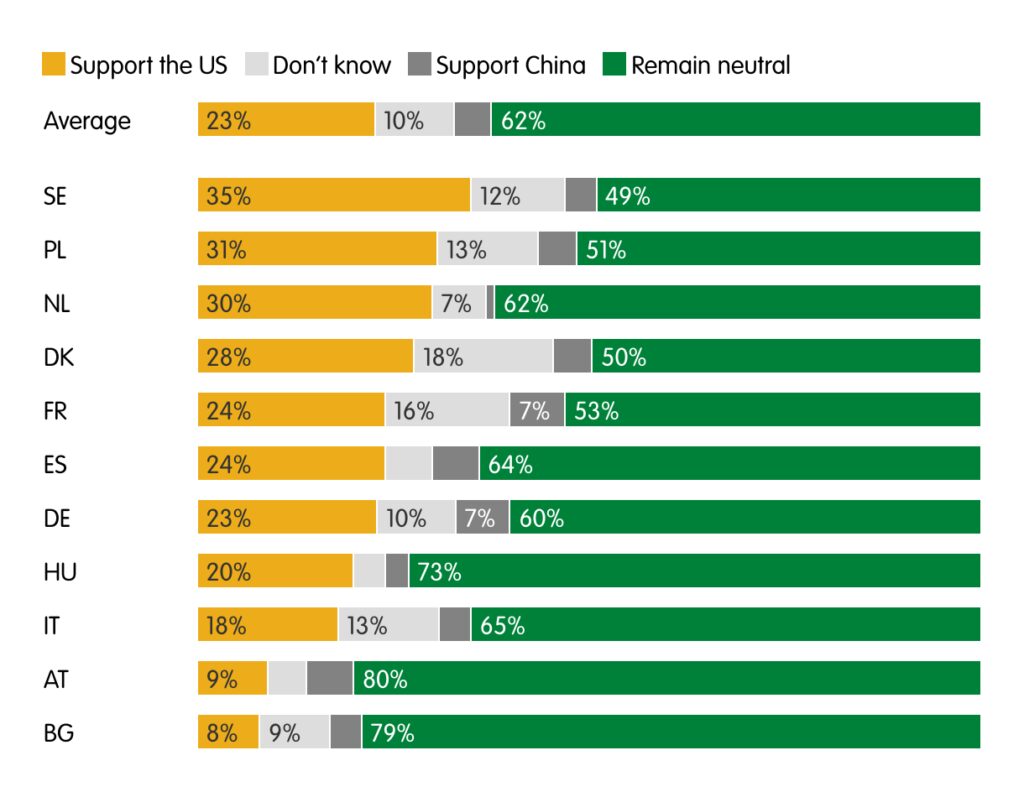

The perceived closeness of Europe to the US does not translate into a willingness to support the US against China in a hypothetical conflict over Taiwan. Despite America’s involvement in standing up to Russia, few Europeans believe that they should return the favour. If a conflict broke out between the US and China over Taiwan, on average, only about a quarter would like their country, or Europe, to take America’s side, whereas a clear majority would like to remain neutral. Americans would find the most supporters among the populations of Sweden, Poland, the Netherlands, and Denmark – but even in these countries, majorities (or 49 per cent in the case of Sweden) would opt for neutrality.

Thus, Europeans do not seem to share the view held by many American strategists that NATO’s eastern flank and the Indo-Pacific are two interconnected theatres (for example, due to the cooperation between Russia and China). Nor do they apparently consider the fact that it will be more difficult for American decision-makers to vote in favour of maintaining US involvement in Europe if Europeans signal that they want to stay out of the conflict that is most important for the US.

On this issue, it matters whether people see the US as Europe’s, and their country’s, “ally” or “partner”. Those who consider the US to be an “ally” are much more willing to take America’s side in the case of the latter’s war with China over Taiwan than those who consider the US to be just a “partner”. EU and US policymakers will therefore need to be increasingly clear about the degree of their alliance.

What the public wants

To strengthen European sovereignty, European leaders will need the public’s backing. They need to understand three features of how European citizens approach foreign policy topics.

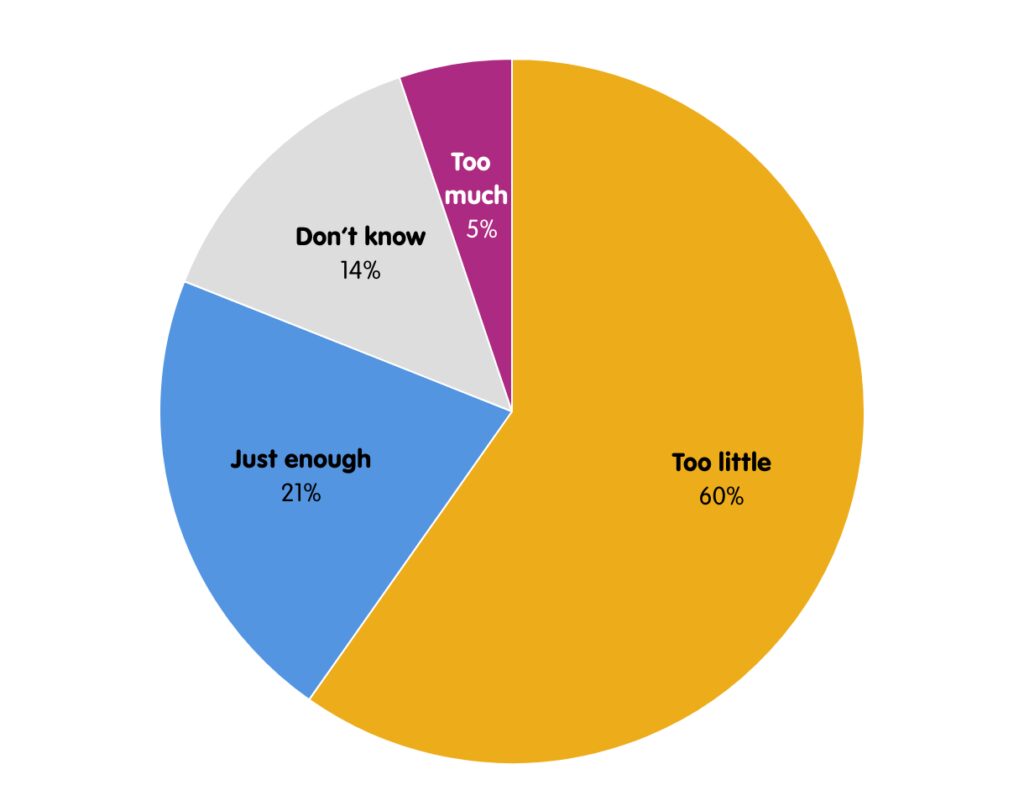

The first concerns the European public’s demand to have a greater say on foreign policy matters. On average, 60 per cent of respondents think their government is not listening to them enough when making foreign policy decisions. If European leaders want the public on board, they will need to demonstrate that they are taking their citizens’ voices seriously.

Secondly, European citizens seem to base their opinions on foreign policy on current circumstances, rather than possible future scenarios, which could cause abrupt changes to the status quo. For example, our study shows that European citizens typically agree that if Donald Trump returned to the White House, the transatlantic alliance would be weaker. But they do not think this is likely within the next two years. This may temper their support for more ambitious steps towards beefing up European defence capabilities. Similarly, the majority of Europeans consider a military confrontation between the US and China as unlikely and are seemingly not particularly concerned by Europe’s economic interdependence with China.

If European leaders were to base their actions on the expectations of the public, they would fail to prepare for highly disruptive scenarios – with potentially devastating consequences for European security. They should therefore enter into an active conversation with their publics to prepare them for various geopolitical scenarios and difficult decisions and communicate the dangers of inaction to them.

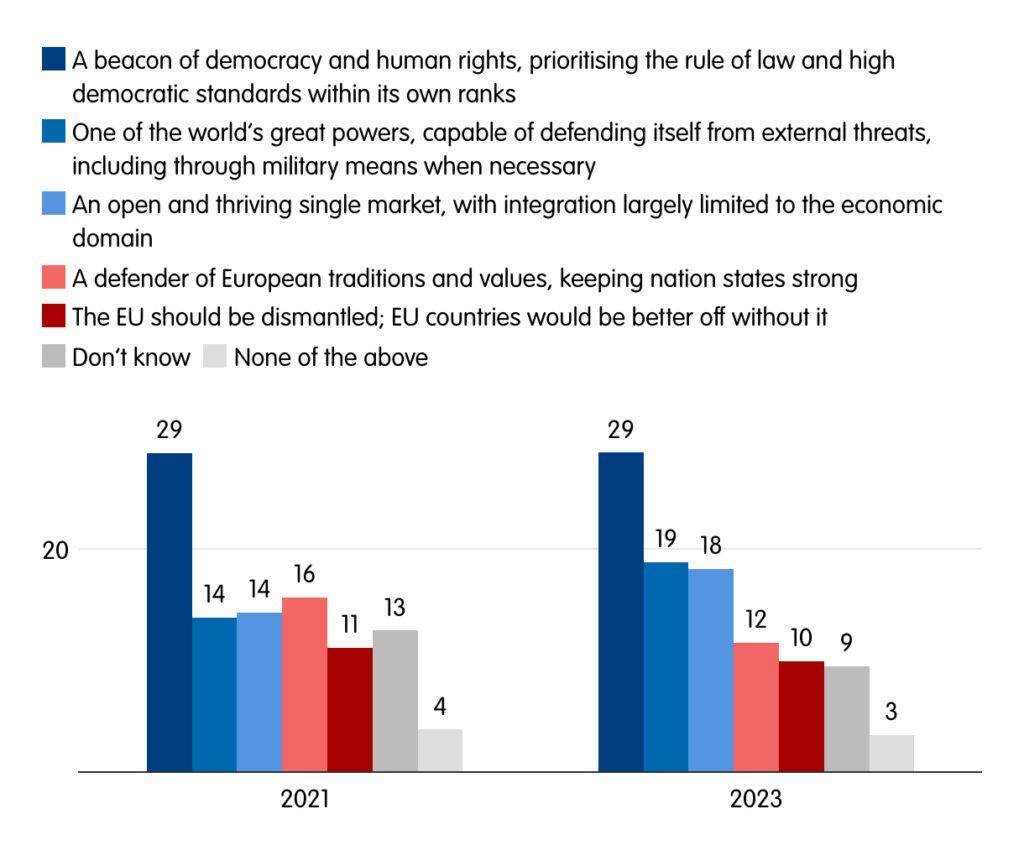

Finally, the European public displays a remarkable attachment to a values-based foreign policy. When asked about the EU’s role, the largest group of respondents think it should be a “beacon of democracy and human rights”. This was also the prevailing view two years ago, when we first asked this question. The war in Ukraine has not produced disillusionment with the EU’s values-based foreign policy or prompted people to value hard power over soft power. While there has been a slight increase in the proportion believing that Europe should be one of the world’s great powers, this proposition is still far less supported than the one that emphasises values. Europeans clearly want Europe’s foreign policy to be about something more than just a power struggle; for them, it should also have a normative element.

Therefore, when European leaders adapt their policies to an increasingly competitive world, they should not simply parrot other great powers. They need to consider the importance of the continent’s soft power. And when they advocate for European sovereignty, they need to present it as a hard-power addition to the mix – rather than as a substitution of the continent’s earlier idealism.

Uniting leaders and the public

European leaders cannot lead the public against its will: a purely pedagogical approach would likely be perceived as patronising. It would reinforce disenchantment with mainstream politics and fuel populism, ultimately making it even harder for the EU to adjust its foreign policy to new challenges. But European leaders cannot just follow the public either. They need to look for points of agreement, while preparing the public for future possibilities and trying to get their support for less popular policies that would respond to abrupt changes. They need to identify the public’s openness to major foreign policy initiatives and act on it – while acknowledging the limitations of their support.

The US

A majority in all countries in which we polled believes that Europeans cannot always rely on the US – and that they, therefore, need to look after their own defence capabilities. European governments should be emboldened by this public support to invest more in European defence and strengthen their defence and foreign policy coordination.

But policymakers will also need to clarify to the public that investment in European defence does not signify Europe’s willingness to go it alone. European citizens still broadly support the transatlantic relationship, with around 30 per cent of Europeans seeing the US as an “ally” and 40 per cent seeing it as a “necessary partner” with whom they must strategically cooperate. Leaders will therefore need to explain that investment in European defence sovereignty would make Europe a better partner for a stronger transatlantic relationship – while hedging against the possibility that the US might focus on other regions. Leaders can help their case by raising the public’s awareness about the various scenarios that could play out in the US. On this point, they should lead the public, which does not seem to fully consider the consequences of possible abrupt changes in Washington’s foreign policy orientation after 2024.

China

Similarly, European leaders can find some common ground to reduce China’s influence in Europe, given that citizens seem sceptical of China’s practical economic presence on the continent. But European citizens do not seem to think that Europe could or should decouple from China, as it has done from Russia, even if they are well aware that China and Russia have entered into a close partnership.

Leaders should therefore communicate the risks of Europe’s more abstract and distant interdependence on China. They should also point to various scenarios that could play out between the US and China. While remaining neutral in the case of great power confrontation is an appealing idea, a US-China confrontation would have a massive impact on Europe’s trade and economy at a minimum and European countries would certainly not be neutral bystanders. In addition, the US would likely demand loyalty from Europeans, reminding them of America’s pivotal role in ensuring a strong Western response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Leaders therefore need to engage in a public discussion about the dangers of failing to prepare for such a scenario.

Leaders could also explain how their approach is based on European values. For example, Europeans should avoid excessive dependencies on China if they want to defend human rights and democracy. Leaders should also explain that strengthening Europe’s hard power would help defend the normative elements of its foreign policy and allow them to gain credibility and efficiency – and ensure that Europe preserves its autonomy to place them at the centre of its dealings with the rest of the world if it chooses to.

Russia

Last but not least, European leaders should not get carried away by possible disagreements about Europe’s future relationship with Russia. The form of this relationship will be highly contingent on the outcome of the fighting, the result of hypothetical peace negotiations, and the possibility of a change in government in Moscow. Seeing Europeans divided on this point today is in the Kremlin’s interest, but it is certainly not in Europe’s.

Instead, European leaders should focus on maintaining their current unity. They should start discussing what Europe’s limited relationship with Russia could look like in the future according to these different scenarios. This would not only prepare the ground for a future political consensus on Europe’s Russia policy, but it could also send a useful signal to the Russian population about the benefits of a negotiated peace.

*

European citizens may be only slowly adapting to the new reality of an increasingly confrontational world. But the shifts that we observe in the public’s views on China, the US, and Russia can pave the way for building a new European foreign policy consensus. European leaders should recognise the public as, at the very least, the “necessary partners” in that endeavour.

Methodology

This report is based on a public opinion poll of adult populations (aged 18 and over) conducted in April 2023 in 11 EU countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Sweden). The total number of respondents was 16,168.

The polls were carried out for ECFR as an online survey through Datapraxis and YouGov in Austria (1,000 respondents; 6-12 April), Denmark (1,019; 6-11 April), France (3,087; 6-14 April), Germany (3,023; 6-13 April), Italy (1,000; 6-12 April), Poland (1,525; 6-18 April), Spain (1,502; 6-12 April), and Sweden (1,003; 6-12 April); and through Datapraxis and Alpha in Bulgaria (1,000; 6-19 April); Datapraxis and Szondaphone in Hungary (1,002; 6-20 April); and Datapraxis and Analitiqs in the Netherlands (1,007; 4-13 April). In all these countries the sample was nationally representative of basic demographics and past votes.

For certain questions – concerning the perception of other countries as allies, partners, rivals, or adversaries; the future relationship with Russia; and the position to be adopted in the event of a US-China conflict over Taiwan – national samples were split so equal numbers of respondents answered from the perspective of Europe and from their own country.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News