With U.S.-China ties at a low point, the resumption of high-level dialogue is a good sign — but there’s a long way to go to improve the relationship.

Over the weekend, Secretary of State Antony Blinken finally made it to Beijing, where he met with senior-level Chinese Communist Party officials, including Xi Jinping. This trip was originally scheduled for early February but delayed nearly five months following the U.S. detection of a Chinese spy balloon hovering over American territory. Already on a downward trajectory before the balloon debacle, U.S.-China relations have continued to spiral since, as high-level communication has been on pause. While no major breakthroughs were made in Beijing and both sides stuck to their boilerplate talking points on issues of disagreement, the resumption of high-level dialogue is a positive step.

USIP’s Rosie Levine, Alison McFarland, Alex Stephenson and Carla Freeman discuss the signals coming out of Blinken’s trip, how major areas of disagreement were addressed, where stalled military-to-military talks stand and what comes next.

What’s the good news coming out of Secretary Blinken’s visit to China?

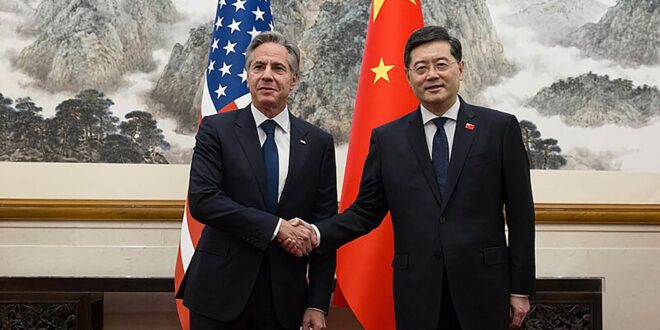

Levine: Blinken’s visit to Beijing brought him into conversation with the highest ranks of foreign policy decisionmakers in Beijing — he met with Director of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Foreign Affairs Office Wang Yi, Foreign Minister Qin Gang, and General-Secretary Xi Jinping. Set upon the backdrop of meetings that failed to happen recently — from the Chinese declined Austin-Li meeting on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue, to the postponement of Blinken’s trip to Beijing — the very fact that this trip happened is a positive development and sends a powerful signal that high-level diplomatic relations between the two superpowers may begin to normalize.

According to the State Department’s readout of the visit, the two sides discussed a joint commitment to “address shared transnational challenges, such as climate change, global macroeconomic stability, food security, public health, and counter-narcotics.” The Chinese readout mentioned other specific areas of cooperation including people-to-people exchanges, educational exchanges and a commitment to establish issue-specific working groups, which were promised at the Biden-Xi meeting in Bali last November but never established. This list, and a commitment to establishing working-level channels to solve problems, point toward productive paths forward for the United States and China to rebuild trust and tackle shared challenges too large for either nation to handle on its own.

There were no illusions that one visit would reset relations between the two countries, but it does demonstrate that there is an appetite for further diplomacy. This goodwill will likely open the door to continued high-level diplomatic interactions throughout the rest of the year: Blinken’s meetings concluded with an agreement that Qin would visit the United States. This is expected to pave the way for a potential meeting between President Joe Biden and Xi in San Francisco on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders’ Summit this November.

Was there any progress on major points of disagreement, like Taiwan, trade and China’s stance on Russia’s war on Ukraine?

McFarland: Although both sides have spoken positively of the visit, with Xi (in the State Department transcript) alluding to agreements reached on “some specific issues,” no significant progress was announced on major points of disagreement. This is not surprising given the tense backdrop of current U.S.-China relations and the low expectations given for the visit, with Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs Daniel Kritenbrink stating ahead of the trip that the intent was not to have “some sort of breakthrough.” With this in mind, it makes sense that many of the talking points provided by the two sides on the above areas of disagreement were familiar reiterations of each country’s position, rather than innovative proposals with bold paths for resolution.

On the Taiwan question, both sides repeated standard talking points. Wang reasserted that the Taiwan question is one of China’s “core interests” and there is “no room for compromise or concession” while Blinken reaffirmed that no changes have been made to the U.S. “One China” policy. With respect to trade, Blinken pushed forward the more recent rhetoric of “de-risking” — rather than “decoupling” from China — referencing Secretary of Treasury Janet Yellen’s congressional testimony that it would be disastrous to “stop all trade and investment with China.” However, Yang Tao, director-general of the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s department of North American and Oceanian Affairs, rejected this distinction when speaking to the media about Blinken’s visit and described de-risking as “de-Sinicization.”

On Russia’s war in Ukraine, Yang maintained Beijing’s neutral position, stating that Beijing would choose the side of “peace” and “political settlement.” Worryingly though, China did not reiterate its call for nuclear weapons to not be used. Blinken reiterated points made in May about welcoming China to play constructive role in Ukraine and spoke positively about Beijing’s reassurances that it would not provide Russia with lethal assistance, saying that he had not seen evidence to the contrary. Nonetheless, he expressed concerns over Chinese companies that may be providing technology to Russia that could be used against Ukraine.

In his discussion with reporters, Blinken stated that he came to Beijing to “make clear our positions and intentions in areas of disagreement,” something that both sides appear to have done. While talks may not have moved very far beyond that, the clear signaling of expectations ahead of the visit meant that a lack of major breakthroughs on these topics was anticipated. It also does not detract from the positive outcomes mentioned above, such as opening a path for more high-level interactions.

Why is China still refusing to revive military-to-military dialogues?

Stephenson: Blinken’s visit to Beijing led to some constructive steps towards stabilizing bilateral relations, with one big caveat: the two militaries still aren’t talking. The United States and China haven’t held military-to-military talks since at least August 2022, when Beijing canceled three defense dialogues in the wake of then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan. Since then, leaders in Washington have repeatedly urged their counterparts in Beijing to re-open vital communications channels, but to no avail. Meanwhile, the Chinese military is engaging in increasingly risky behavior.

Beijing’s unwillingness to revive communications channels stems from its approach to crisis management, which is fundamentally different from Washington’s approach. For China, the American military presence along its periphery is the primary driver of risk, a point which was reiterated by Chinese Defense Minister Li Shangfu at the recent Shangri-La Dialogue. Beijing sees crisis communications mechanisms — including military dialogues and the defense telephone link — as a “safety net” that enables more provocative U.S. military activities in the region. Moreover, Beijing views targeted escalation as one way to manage crises, using calculated risk to deter unwanted behavior without triggering violent conflict.

Unfortunately, Washington and Beijing’s diverging approaches to crisis management will likely lead to more close-calls and closed communications channels. High-level dialogue between the two defense chiefs is particularly unlikely while Li remains under U.S. sanctions. Beijing considers the sanctions demeaning and an obstacle to contact between Li and Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin. Still, reviving certain levels of dialogue is not impossible. Even if Li-Austin talks are stalled, the United States should continue pressing Beijing to bring back some of the mechanisms canceled last year, such as the Maritime Military Consultative Agreement and the Defense Policy Coordination Talks. In the absence of consensus on “crisis communications” or “crisis management,” figuring out a way for the militaries to talk at any level will be a useful first step.

What comes next?

Freeman: In addition to laying groundwork for more high-level diplomacy between Washington and Beijing, Blinken’s visit to Beijing also raised hopes for a face-to-face meeting between Xi and Biden. Qin’s acceptance of a visit to Washington adds to the expectation for a Biden-Xi summit during this fall’s APEC meeting that could widen opportunities for a deeper thaw in U.S.-China relations. However, the bilateral relationship between the two countries remains fragile and building momentum toward a meeting between Biden and Xi amid many frictions between the countries will be challenging. Beijing’s angry reaction to Biden’s characterization of Xi as a “dictator” in off-the-cuff remarks made just days after Blinken met with the Chinese leader was a swift reminder that, despite the desire to improve ties signaled by both sides in Beijing, progress in bilateral relations can be easily derailed in an atmosphere fraught with tension and mutual mistrust.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News