The Debate Over How to End the War

There Can Be No Negotiations With Putin

In “An Unwinabble War” (July/August 2023), Samuel Charap makes the case that Washington should “start facilitating an endgame” for the war in Ukraine. His argument rests on his assumption that a definitive outcome is out of reach. Russia cannot conquer Ukraine, in his view, but neither can Ukraine expel Russian troops from its 1991 borders. Yet there is a reason that Ukraine defines victory as liberating every inch of its territory. Any territorial concession to Russia, even a small one, would invite further aggression. The pretext might be different, but the objective would be the same: subduing Ukraine. As long as it avoids outright defeat, Russia will use any disputed territory as a launching pad for its next round of expansion, as it did after the Minsk agreements that were supposed to end the conflict in eastern Ukraine in 2014 and 2015.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s paramount objective is to avoid a crushing defeat on the battlefield. Nothing less than the survival of his regime is at stake, as the humiliating mutiny led by the Wagner mercenary chief Yevgeny Prigozhin demonstrated last month. Therefore, Russia needs to create at least the illusion of military achievement. Doing so will allow the Kremlin’s propaganda machine to spin a narrative of revanchism and stoke popular demands for further aggression against Ukraine. This was the playbook Russia followed in Chechnya in the first decade of the millennium, when Putin leveraged claims of success in the fight against “terrorism” to concentrate power, weaken democratic institutions, sideline local authorities, and pacify a rebellious region.

But even as Putin fights for his political life, many in the West are still considering short-term solutions that would help keep in him power. Sixteen months of war in Europe have not forged an unconditional anti-Putin coalition. Yet a unified Western policy on Putin, or rather on the need for his removal, is essential for marshaling the material support Ukraine needs to win a decisive victory on the battlefield. The sooner Western governments reach a consensus on Putin—as they did on Slobodan Milosevic in Yugoslavia, Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and Bashar al-Assad in Syria—the sooner Ukraine will be able to destroy Russia’s invading forces and bring the war to an end.

Throughout the course of the conflict, Ukraine has shown that with timely and consistent help, it can prevail on the battlefield even when its troops are outnumbered. Just as American and British handheld Javelin and NLAW missile systems helped Ukraine halt the advance of Russian tanks around Kyiv in the early stages of the invasion, American high-mobility artillery rocket systems known as HIMARs have since changed the face of the conflict and helped Ukraine liberate a significant amount of territory previously occupied by the Russians. Such aid, when promptly and consistently supplied, dramatically improves the odds of a decisive Ukrainian victory over Russia.

Moreover, advances on the Ukrainian battlefield can catalyze advantageous political developments in Russia, as Prigozhin’s brief rebellion showed. A popular Russian military leader who is stymied on the battlefield could end up toppling Putin in a coup. The argument, voiced by some Western analysts, that Russia will continue to threaten Ukraine no matter how much territory it reclaims fails to consider this possibility. As long as Russia is led by Putin, who has stated publicly that he believes “the whole military, economic, and information machines of the West” are turned on Russia, Moscow will remain a permanent threat not just to Ukraine but to the broader transatlantic community. A post-Putin Russia need not see everyone as a threat—and it could cease being a threat to itself.

This is why a unified Western policy on Putin is crucial. If the goal is to prevent Russia from threatening democracies around the world, allowing it to reach an armistice with Ukraine won’t do much good. Ukraine and its allies must aim to make Russia less anti-Western. Regardless of what happens at the negotiating table, therefore, Putin cannot remain in power.

A post-Putin Russia need not see everyone as a threat.

Some Western officials worry that such a policy would invite dangerous uncertainty. Who would succeed Putin and how that person would behave are unknowable in advance, and some analysts have warned that the collapse of Putin’s regime following a military defeat could trigger the dissolution of Russia as the world knows it today. Such fears have prevented Western governments from supplying arms to Kyiv in quantities sufficient to win the war. The effect has been to prolong the conflict and make it more costly for Ukraine and the world.

To break this vicious circle, Ukraine must finally secure the weapons it needs to prevail on the battlefield and an assurance from its Western partners that the leaders of a post-Putin Russia will have the consent of Ukraine. Just as many Western governments support the exiled Belarusian opposition politician Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya as a potential political leader of Belarus, and Kyiv supports the members of the Kastus Kalinouski Regiment (a Belarusian volunteer unit fighting for Ukraine) in their ambition to participate in the political life of a liberated Belarus, Ukraine and its partners should support an alternative to Putin in Russia. Opposition politicians such as Vladimir Kara-Murza and members of Russian military units fighting against Moscow—such as the Russian Volunteer Corps and the Freedom of Russia Legion—should be endorsed by democratic countries and aided in their quest to return Russia to the pantheon of civilized nations. Such efforts to transform Russia’s political landscape are essential because the conflict can be resolved permanently only when Ukraine and its neighbors feel safe from further Russian encroachment.

This is why an armistice like the one that ended hostilities in Korea in 1953 cannot work for Ukraine. That agreement left intact a hostile authoritarian regime in North Korea that since 2006 has threatened not just South Korea but the entire world with nuclear weapons. The peaceful reunification of Germany in 1990 has been offered as another potential model for Ukraine, but it was made possible by regime changes in Hungary, Austria, and Germany itself. The end of communist rule in Hungary in 1989 set the stage for the so-called Pan-European Picnic, a massive demonstration during which Hungary and Austria opened their borders and allowed several hundred East German citizens to pass through their territory on their way to West Germany. Demonstrations on both sides ensued, the Berlin Wall came down, and the rest is history. But the bottom line is that the political regime in East Germany had to fall before the country could be reunified.

Russia must make a similarly fundamental change to both its domestic and foreign policies before returning to the community of responsible nations. First and foremost, the leaders of a post-Putin Russia would have to demilitarize the country, directing funds away from the army and toward desperately needed social services. In addition, they would have to curtail Russia’s state propaganda machine, which breeds hatred and hostility. As long as the Kremlin opposes the Western, transatlantic community to which Ukraine belongs, a lasting peace will remain impossible. For these reasons, the war will continue until Russia is defeated and Putin’s regime falls. The only question is: How long will that be?

Ukraine seeks as much military assistance as possible not just because it has the clearest interest in swiftly ending the war but also because it knows that only victory over—and not just peace with—Russia can guarantee freedom, democracy, and prosperity for Ukraine and the West. And Putin has already revealed how ugly the alternative might be.

Ukraine Should Aim for Victory, Not Compromise

Alina Polyakova and Daniel Fried

The problems in Samuel Charap’s essay start with its title, “An Unwinnable War.” Charap assumes that Ukraine cannot defeat Russia and, moreover, that it doesn’t even matter whether Ukraine pushes back Russian forces and liberates more of its land. Russia, Charap argues, will pursue its attempt to subjugate Ukraine no matter what. Therefore, the United States must immediately begin crafting a diplomatic settlement that freezes the status quo and leaves Ukraine with promises of assistance when Russia resumes aggression but no firm security guarantees akin to NATO’s Article 5. This argument profoundly misunderstands the Russian-Ukrainian war and leads to dangerous conclusions that, if acted on, would leave Washington and its allies in a far more vulnerable position vis-à-vis not only Russia but China, too.

Charap overestimates Russia’s strength and underestimates Ukraine’s resolve. At the outbreak of Russia’s invasion last year, many Western experts and most Western governments mistakenly assumed that Kyiv would fall in a matter of days, that Ukrainians would not fight, and that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky would flee or capitulate. The Kremlin made similar assumptions. The war’s course to date has disproved all these predictions. Ukraine stopped Russian forces from taking Kyiv, defeated them in Kharkiv, and drove them back across the Dnieper River, liberating Kherson. Putin’s Bahkmut offensive has deepened his costly mess.

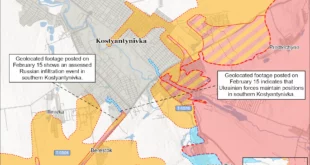

Recent estimates put Russian casualties since the beginning of the full-scale invasion at up to 250,000. Russia has proved unable to guard its border from Ukrainian raids. Ukraine’s counteroffensive may not succeed in fully liberating all its currently occupied territories, but it could make significant progress in taking back land in the Donbas and breaking through Russia’s land bridge to Crimea, thus undermining Russia’s use of Crimea as a staging ground. If Ukrainian forces do manage to put Crimea itself within artillery range as the offensive proceeds over the next several months, Russia may be forced into an untenable position.

Charap nevertheless asserts that “15 months of fighting has made clear that neither side has the capacity—even with external help—to achieve a decisive military victory over the other.” He still assumes that Ukraine cannot force anything better than a military stalemate. Even before the Wagner mercenary chief Yevgeny Prigozhin mutinied against Putin, this was a questionable assumption. And Ukraine is not even operating at full force yet. It has not received the complete repertoire of Western systems, including American F-16s: the Biden administration just recently agreed to allow allies to transfer them to Ukraine. Nor has Ukraine received enough long-range missiles, even though the United Kingdom delivered Storm Shadow long-range cruise missiles in May.

Because the Ukrainians are only partially equipped, Kyiv’s full warfighting capabilities are still unknown. But the pattern over the last 15 months is clear. Ukrainians, despite losses, have shown capacities—to adapt, learn quickly, and rapidly deploy new systems in the theater—that far exceed Russia’s. If anything, the problem has been the lag, for political and logistical reasons, in the delivery of Western equipment. There is no telling what the Ukrainians will be able to achieve once all the promised systems are on the battlefield.

Kyiv’s full warfighting capabilities are still unknown.

Charap also wrongly assumes that Putin has infinite resolve to continue prosecuting this war—that time is on his side. But Putin did not expect a drawn-out war, which would have required far more planning, training, and investment in military production than the Kremlin undertook. Russia’s war effort has stumbled from one failure to the next: infighting among the military command, ammunition shortages, a sudden and disorganized mobilization of reluctant conscripts, confused and contradictory propaganda, and a lack of drone capabilities. (In desperation, Russia has had to source drones from Iran.) It is also worth noting that Russia has lost plenty of wars: the Crimean War, the Russo-Japanese War, World War I, and the Afghan war. Each defeat provoked domestic stress and upheaval.

Events that have unfolded since the publication of Charap’s article only further confirm his overestimation of Russian resolve and stability. Although Prigozhin’s uprising was not a coup, an armed military group took over a Russian city—Russia’s operational hub for the war in Ukraine—and marched to within 125 miles of Moscow. A deal supposedly brokered by Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko saw Prigozhin relocate to Belarus. Others will learn the lesson that rather than lashing out when cornered, Putin negotiates.

But evidence of stress in the Russian ruling circles was abundantly visible even before Prigozhin’s rebellion. For months, Russian military bloggers revealed bitter infighting between the intelligence services and within the Russian military command. In private, Russian elites have confessed their disapproval of the war to exiled Russian journalists, apparently to try to keep their reputations clean in anticipation of a Russian loss.

Charap argues for an armistice modeled on the one that ended the Korean War, imperfect but justified by the relative peace it delivered and the prosperity South Korea subsequently enjoyed. But he fails to acknowledge that the relative peace on the Korean Peninsula has for 70 years been secured by a large U.S. military presence. Almost 30,000 U.S. troops still protect the peace there. Charap’s plan includes no U.S. forces for Ukraine’s defense, nor does he advocate NATO membership for Ukraine.

Charap also offers the U.S.-Israeli security arrangement as a model for the kind of relationship Ukraine should have with the United States. In practice, that would mean leaving Ukraine with a lot of U.S. military assistance but no firm guarantees. That arrangement works for Israel only because Israel is far stronger than all its potential adversaries combined. Ukraine is not in that position.

Ukrainians would rather live in a free Ukraine with no water and no electricity than under Russia’s thumb.

Charap dismisses the significance of Ukraine’s having even partially pushed back the Russian occupation. But Ukraine’s liberation of Russian-occupied land makes a huge difference to the liberated. As the world witnessed during the joyful celebrations after the Russians retreated from the outskirts of Kyiv and, later, from Kherson, Ukrainians under Russian occupation live in fear and face terrible atrocities. Ukrainians have made clear that they would rather live in a free Ukraine with no water and no electricity than under Russia’s thumb.

A military stalemate is indeed possible. And at some point, negotiations with Russia will be needed to end this war. But Ukraine should start negotiating only when it is in the strongest possible position; it should not be rushed into talks when Russia shows no interest in any settlement terms other than Ukraine’s surrender. Starting negotiations now would mean accepting Putin’s maximalist terms. If Russia suffers further setbacks on the battlefield, however, talks could proceed from a better starting place. The most important point, which Ukraine’s allies agree on, is that Ukraine must define the right moment for negotiations. That may or may not be when all of Ukraine’s territory is liberated. The key is for Ukraine to maintain flexibility in its decisions about its territory and the path toward a just peace.

If and when negotiations take place, they must be accompanied by security arrangements for Ukraine that would prevent Russia from regrouping and launching another attack. NATO membership for Ukraine would do the trick; anything less than an unambiguous commitment to Ukraine joining NATO with a clearly delineated path forward would only set up another round of Russian aggression and would also signal to China that aggression can pay. Since Ukraine’s accession to NATO will take time, in the interim enhanced security arrangements between key NATO members and Ukraine need to be agreed on and implemented. Experience shows that equivocation about Ukraine’s place in Europe invites Russian aggression rather than deters it. And many examples over the past century indicate that appeasement never leads to durable peace.

Charap’s argument rests on the premise that, in the foreseeable future, Ukraine cannot win a sustainable victory that includes recapturing all its territory. Essentially, he concludes that ambiguity about its place in Europe will be Ukraine’s fate. But he is far too pessimistic. Kyiv’s friends should not assume that Russia holds all the cards.

Russia Can Be Stopped Only on the Battlefield

Angela Stent

The death, destruction, and humanitarian crisis in Ukraine is enormous. That a brutal large-scale war could take place on the European continent seemed almost unimaginable two years ago. The accumulating costs—plus the uncertainties of what will happen both on the battlefield and in the 2024 U.S. election—provide reason to seek some way to stop the violence. And Samuel Charap has laid out a reasonable case for negotiation.

But there is a huge problem in trying to negotiate with President Vladimir Putin’s Russia, and that is Russia itself. Moscow has broken every security-related agreement it has signed with Ukraine in the past 30 years. These include the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances, whereby Ukraine renounced its nuclear arsenal—at the time, the third largest in the world—in return for a pledge by Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States to respect its independence, sovereignty, and existing borders. That was followed by the 1997 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership between Ukraine and the Russian Federation in which both sides agreed to work toward a strategic partnership. At the time, Boris Yeltsin, on his first official visit to Kyiv as Russian president, said, “We respect and honor the territorial integrity of Ukraine.” Yet his handpicked successor, Vladimir Putin, repeatedly made it clear that he had no intention of accepting these agreements. In 2008, he told U.S. President George W. Bush that “Ukraine is not a real country.” Three years later, he told former U.S. President Bill Clinton that he did not feel bound to honor any agreements on Ukraine signed by Yeltsin. And in 2021, Putin published a 5,000-word essay called “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” in which he argued that there was no such thing as Ukrainian nationality. How can one assume that this time Russia’s behavior would be any different?

As Ukraine’s counteroffensive unfolds, it is premature to write that “neither side” can “achieve a decisive military victory” or claim that “regardless of how much territory Ukrainian forces can liberate,” Russia will “pose a permanent threat to Ukraine.” The fighting is intense, and this counteroffensive is the first in what will be a series of offensives playing out over the coming months. Ukraine appears to be making incremental hard-fought territorial gains, but Russia is claiming that it is repulsing them. If Ukraine can secure more and better Western weapons, then it could make more gains. Its soldiers’ morale remains high as they fight a battle for national survival. Russian troop morale is dwindling, and the armed forces continue to perform below par. And since Charap published his article, more evidence of Russian weakness has emerged. Yevgeny Prigozhin, the head of the Wagner mercenary group, staged a mutiny, calling into question Putin’s grip on Russia. And even before his rebellion, Prigozhin admitted that Ukraine was building one of the strongest armies in the world.

NO ONE TO TALK TO

Putin’s war aims are not limited. His original objectives were to conquer all of Ukraine, overthrow its government, and ensure Russia’s perpetual domination of the country while simultaneously eradicating Ukrainian statehood and nationhood. Although Putin failed to take Kyiv in three days, there is no evidence that he has abandoned those goals. From his perspective, they may just take longer to accomplish. As long as he remains in power, or if his successor shares his imperial mindset, Russia’s aspirations in Ukraine will not change. At this point, he has repeatedly said that the minimum conditions for negotiating with Kyiv would be the Ukrainian acceptance of the loss of the four territories that Moscow claims to have annexed, even though Russia does not fully control any of them. How can Ukraine survive as a viable state—and indeed maintain national unity—with the loss of the Donbas, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia?

Charap acknowledges that “the two countries will be enemies long after the hot war ends” but then goes on to suggest that an armistice involving a form of a frozen conflict or some territorial concessions by Ukraine is probably the best way forward. Given Russia’s past and present behavior, it is clear that an armistice would be a temporary solution while Russia regroups and plans its next attack or formulates new ways of undermining Ukraine. The Korean solution, which Charap considers the most likely way the war will end, would also be most disadvantageous for Ukraine. He notes that 70 years after the Korean War ended, South Korea has done well economically despite the fact that the two Koreas never signed a peace treaty, but he neglects the differences in the two situations. North Korea does not occupy South Korean territory. Who would invest in a Ukraine that had signed an armistice with Russia involving territorial concessions when the chance remains that Russia could resume its aggression at any point?

Charap also raises the “porcupine” strategy, the idea that Ukraine should negotiate with Russia on the premise that the West will continue to arm Ukraine after the conflict is over to ensure that it could deter any future attack by Russia. The U.S.-Israel model is the basis for this, an alternative to NATO membership. But Israel has nuclear weapons to reinforce its deterrence capabilities, and few are suggesting that Ukraine should restart its nuclear program as a solution to fend off the next Russian attack.

Finally, Charap cites the lack of diplomacy with Russia and proposes the appointment of a special presidential envoy to facilitate regular communication with U.S. allies and Ukraine as well as with Russia. The reason that diplomacy between the West and Russia is almost nonexistent is that European and U.S. representatives have been consistently lied to by Russian officials both in the run-up to the war and since it began. When Western diplomats responded to the fanciful “treaties” presented by Russia to the United States and NATO in December 2021, they met with Russian prevarication, including outright denials that Moscow had any plans to invade Ukraine. The leaders of France and Germany have occasionally talked with Putin since February 2022 but to no avail. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken has also had several unproductive conversations with Sergey Lavrov, his Russian counterpart. So with whom would this U.S. envoy talk in Russia? Moscow has shown no sign of interest in having serious conversations with Ukraine or the West.

Charap cites as a model the Contact Group for the Balkans, a group of representatives from key countries and international institutions that met regularly in the 1990s and 2000s to bring peace and stability to the war-torn region. But the Contact Group operated in a different time. During the Balkan wars, despite disagreements, the Yeltsin administration was willing to cooperate with the West and did not see it as the enemy. Russia has since changed. Russian officials in the past few months have amplified their criticism of the West for starting and prolonging the war and have even blamed the West for Prigozhin’s ill-fated mutiny. Russian forces have doubled down on bombing civilian targets in Ukraine and risk catastrophe in repeated attacks and fighting around the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. And the attempts by the Chinese government, African leaders, and the pope to mediate the conflict have so far failed to moderate Russian actions. Putin continues to believe that he can outlast the West and win on the battlefield. The United States and its allies have learned from their past mistakes to take Putin’s words seriously when he repeats his commitment to “denazify” and demilitarize Ukraine as well reverse what he calls the “greatest geopolitical tragedy of the twentieth century,” the breakup of the Soviet Union. Putin will continue until Russia’s aggression is stopped on the battlefield, not the negotiating table.

Charap Replies

I welcome these responses to my article and Foreign Affairs’ initiative to further the debate on the important issues at stake. My argument begins with an analysis of the likely trajectory of the Russian-Ukrainian war based on the evidence available after 15 months of fighting. It is now clear that neither side is capable of a decisive military victory, whether in the form of regime change or demilitarization of the enemy. Both countries will likely retain significant capabilities after the hot phase of the war ends—capabilities that will allow each to pose a threat to the other indefinitely. Further, neither Moscow nor Kyiv is likely to fully achieve its stated territorial goals and therefore will not recognize the line of contact at the time of cessation of hostilities as an agreed border. As a result, they will be locked in a tense confrontation for the long term.

These fundamental drivers—the mutual ability to impose significant military costs and the persistence of unbridgeable political divides—could produce a years-long conflict that causes immense human suffering, economic hardship, and international instability. But even a long war will not change those fundamentals. Therefore, the United States and its allies should begin to try to steer the conflict toward an endgame. Since talks will be needed but a peace treaty is out of the question, the most plausible ending is an armistice agreement. An armistice—essentially a durable cease-fire agreement that does not address political disputes—would not end the conflict, but it would stop the bloodshed.

The article proposes several measures—such as security commitments to Ukraine and cease-fire support mechanisms—to ensure that any armistice agreement does not become an operational pause. And it suggests steps the United States can take now—appointing an envoy, opening discussions with allies and Ukraine on the endgame, and establishing active channels with Moscow—to facilitate this outcome over the medium term, without sacrificing the existing planks of its policy, including military support to Kyiv.

Neither side is capable of a decisive military victory.

It is notable that only one of the three critiques offers a coherent alternative endgame to the one that I argue is most likely. Dmytro Natalukha demands that the West adopt an explicit policy of regime change in Russia and undertake active measures to oust Russian President Vladimir Putin and install a liberal opposition figure in the Kremlin, including by providing support for the Ukraine-based Russian paramilitary groups that have conducted cross-border raids in recent months. Even if such a policy were to succeed in destabilizing the regime, there is no reason to assume that the next Kremlin leader would agree, as Natalukha insists, to operate with “the consent of Ukraine” and to “demilitarize” Russia. Indeed, the Prigozhin revolt is a stark reminder that alternatives to Putin might be equally if not more problematic for Ukraine and the West. Natalukha’s regime-change endgame qualifies as an alternative to an armistice, but it is more of a dream than a strategy—and maybe a nightmare.

Angela Stent offers well-founded skepticism about negotiating with Russia but says little about how she sees the war ending. She calls for Russia’s aggression to be “stopped on the battlefield, not the negotiating table”—implying, presumably, the destruction of the Russian military. But she offers no suggestions about how this outcome can be achieved. And although Alina Polyakova and Daniel Fried argue that I “overestimate Russia’s strength and underestimate Ukraine’s resolve,” they do not make the case that Kyiv can eliminate the threat posed by the Russian military. And they seem to agree with my fundamental point that, as they write, “negotiations with Russia will be needed to end this war.” But they think that now is not the time because Ukraine can retake more land before the guns fall silent.

I agree that further Ukrainian gains are possible—and, as I wrote, “certainly desirable,” particularly for liberated Ukrainians. But Polyakova and Fried merely assert that the location of the line of control is the central determinant of Ukraine’s future without weighing it against other factors, such as the length of the conflict, the stability of an eventual cease-fire, or the prosperity and security of the areas the Ukrainian government controls.

TIME TO TALK

My critics seem to see diplomacy as a synonym for surrender rather than as an important tool of statecraft. This is an odd and ahistorical view. Starting talks does not require stopping the fight. Conducting negotiations is not the opposite of applying coercive pressure. In fact, negotiations are the means by which states can turn that pressure into leverage to accomplish their goals. As Thomas Schelling wrote in his classic Arms and Influence, “The power to hurt is bargaining power. To exploit it is diplomacy—vicious diplomacy, but diplomacy.” Talks are an instrument for a warring state to further the same objectives it seeks on the battlefield. Historically, they have often taken place during periods of intense fighting. Nowhere in my article do I suggest that Ukraine would have to stop fighting—or that the West would have to cease supporting that fight—in order to start talks.

Further, starting negotiations does not require, as Polyakova and Fried state explicitly and Stent strongly implies, “accepting Putin’s maximalist terms.” Accepting the other side’s maximalist terms is capitulation, not negotiation. A party enters a negotiation in order to move the other side closer to its position. Suggesting otherwise only serves to delegitimize diplomacy.

Stent claims that there is “no evidence” that Putin has abandoned his original, maximalist goal of regime change in Ukraine. In fact, there is plenty of evidence that Putin has been forced by his own failures to ratchet down his objectives. Less than a week after the full-scale invasion began (when it was already clear this was not the cakewalk Moscow had expected), he sent a delegation to talk to representatives of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s government about a possible deal. A little over a month later, Putin withdrew Russian forces from the areas around Kyiv and several northern cities when it became obvious that the Russian military could not take the capital, let alone the country. It is certainly possible, as Stent suggests, that these were merely tactical retreats that do not reflect a shift in strategy. But neither she nor I can read Putin’s mind. And that is precisely why having active channels of communication is so important: to operate on direct knowledge, not assumptions, about the other side’s bargaining position and its evolution over time.

In the absence of negotiations, Putin has no incentive to make preemptive concessions or publicly express anything other than maximalist demands. It is always important to take what he says seriously, as Stent rightly advises, but it is equally important to understand the context in which he is speaking. At a moment when neither Ukraine nor its Western partners are demonstrating a readiness to talk, it would be premature to draw conclusions about Putin’s willingness to bargain based on his public statements. What is clear is that Russia does not have the military capabilities to achieve its maximalist goals. So if Putin insists on them when talks do begin, those talks will not last long.

NO ILLUSIONS

If and when talks are held, they will probably be exceptionally difficult at best—and they might well fail. Stent accurately recites Russia’s litany of broken agreements, lies, and overall perfidy and asks, “How can one assume that this time Russia’s behavior would be any different?” One cannot and should not make that assumption, and I certainly do not. The United States should enter any consultations or negotiations with no illusions about the trustworthiness of Russia and its leaders. But in international politics, one does not get to choose one’s interlocutors. And there is no plausible path to ending the war that does not entail engaging Moscow. So eventually, Washington, Kyiv, Berlin, and others will have to try. This would not be the first time the United States talked to a nefarious regime with a history of deceit in order to stop a war. The U.S. military officers who negotiated the Korean armistice sat across the table from the leaders of the enemy forces that had killed tens of thousands of Americans.

All three critiques of my article dispute the applicability of one or another of the historical comparisons I made to past cases of U.S. conflict diplomacy, be it the Korean armistice, U.S.-Israeli security arrangements, or the Bosnia Contact Group. The circumstances of the Russian-Ukrainian war are unique; no historical analogy is perfect. But these examples teach important lessons and demonstrate that U.S. diplomacy has helped bring bloody conflicts to negotiated ends in the past, even as fighting still raged and even when it seemed as if there would be no way to stop it.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News