The growing importance of Iran for the Russian Federation and the shift in relative power between the two countries has been highlighted by a remarkable set of exchanges between Tehran and Moscow over the past week.

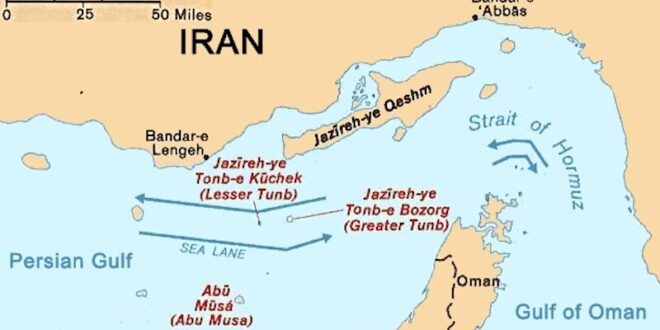

On July 12, Moscow signed on to a declaration by the Arab Gulf states that their dispute with Tehran over the Ormuz Islands should be resolved by negotiations. The following day, Tehran denounced Russia’s position and called the Russian ambassador to Tehran to protest Moscow’s actions. The Iranian Foreign Ministry said, “The three islands belong to Iran forever and issuing such statements contradicts Iran’s friendly relations with its neighbors,” a position quickly echoed by other Iranian officials and commentators.

Two days after that, on July 14, the Kremlin’s special representative for the Middle East, Mikhail Bogdanov, told the Iranian ambassador in Moscow that Russia continues to support without qualification the territorial integrity of Iran. However, on July 17, Tehran responded by saying that these statements were insufficient. The very next day, on July 18, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov telephoned his Iranian counterpart, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, to say that Moscow has “no doubts” about Iran’s territorial integrity, including presumably its control of the three small islands in the Strait of Hormuz. Even so, today, there are indications that the scandal is not dying away, with Tehran demanding compensation for Moscow’s actions regarding the islands (Khabaronline.ir, July 12, 15, 19; Nezavisimaya gazeta, July 12; Realtribune.ru, July 15; Absatz.meda, July 18; Rosbalt.ru, July 20).

Just how infuriated the Iranians are about the original Russian statement was reflected in Tehran commentaries that suggested relations with Moscow could now suffer because the Russian side has violated what is one of Iran’s most significant “red lines” (Happin.az, July 16). This sharp reaction was also felt in statements from Iranian officials reiterating that Iran recognizes the territorial integrity of Ukraine and all other countries, a position that explicitly challenges Russia’s occupation of Crimea and its pursuit of border changes with its neighbor by military means (Nsn.fm, July 18). Some Iranians have even suggested that Tehran’s friendship and cooperation with Russia would be at an end if Moscow did not back away from its support of negotiations over territories Iran considers its own (Absatz.media, July 18).

Three details about this diplomatic crisis are especially noteworthy. First, Moscow had every reason to know that, if it supported the idea of negotiations about islands the Iranians claim, it would face the same kind of problems the Chinese did when they took a similar step earlier. In addition, the Russian authorities had to be aware that such a step would inevitably undercut Moscow’s position on Crimea as well as its growing ties with Tehran (Nezavisimaya gazeta, July 12).

Indeed, the Kremlin was warned about these dangers by Moscow experts. One of their number, Karine Gevorgyan, bluntly observed that what Russia had done in appearing to question the territorial integrity of Iran was “more than a crime; it was a mistake.” She added that, now, Tehran likely will harden its position on Crimea and other issues, something the Russian government cannot possibly want (Nsn.fm, July 18).

Second, the course of this exchange demonstrates not only that there are serious problems in Russian foreign policy decision-making but also that the speed with which the Kremlin backed down all too publicly shows that Moscow clearly feels it needs Iran more than Iran needs Russia. This marks a reversal in the situation many assumed was driving the bilateral relationship and one that Iran from now on is likely to exploit in the future, demanding Russian support for its positions without necessarily feeling compelled to provide Moscow support for all of its actions, particularly in the case of Ukraine. In fact, some Russian analysts are even saying that Tehran may be ready to condemn Russian military actions there—a real reversal of Moscow’s fortunes (Nezavisimaya gazeta, July 12).

And third, the vehemence of Iran’s reaction and Moscow’s readiness to back down also means that, when Tehran “loses interest in developing relations with Russia,” something will likely change in the future, either because of Russia’s increasing isolation over its war against Ukraine, or because Moscow’s missteps, such as the current one with Tehran, will prompt Iran to look for alternative allies. At present, there may seem little likelihood of such a development; but if Russia engages in equally thoughtless diplomacy with regard to Iran in the future, then the prospect that Tehran will decide it cannot trust Russia and turn to others will almost certainly grow (Nezavisimaya gazeta, July 12). While some Russian experts are downplaying this danger, others like Gevorgyan acknowledge that it is something Moscow cannot avoid taking into consideration (Nsn.fm, July 18).

The speed with which Lavrov and the Russian Foreign Ministry acted in this case to correct the error their representatives had made about these three small islands, which are both symbolically and militarily important to Iranians as an indication of their country’s power, suggests that the senior Russian leadership is worried that any loss of influence in Tehran could cost Moscow its recent gains. These would include Iran’s decision to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, its support for Moscow’s position on the Caspian and its willingness to provide Russia with arms for the war in Ukraine (see EDM, March 30, June 7; see China Brief, March 31).

Moreover, in addition to these geo-economic and geopolitical consequences for Iranian-Russian cooperation or any break in that cooperation, there is another possible outcome that may be much on the mind of President Vladimir Putin under the current circumstances. Iran has been carefully promoting its influence in the Muslim regions of the Russian Federation, mindful that a more robust effort in those regions would compromise its relations with the Kremlin. If the Tehran-Moscow relationship does break down, or even if Tehran wants to send a message to Moscow about the costs of such an outcome, then Iran is likely to step up this effort, with incalculable results for Russia’s domestic stability and even territorial integrity (see EDM, November 8, 2022).

That, too, is likely on Moscow’s mind and helps explain why Lavrov acted so quickly in this case. But whether his words will be enough remains very much an open question. Tehran has now seen what Russian officials will do when they are pursuing other interests and may be less willing to accept simple reassurances. If so, the Kremlin may find its bridge to the world’s oceans just as damaged as its ill-fated bridge to Crimea.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News