It has been a while since I published anything long-form commenting on the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, and I confess that writing this article gave me a modicum of trouble. Ukraine’s much anticipated grand summer counteroffensive has now been underway for about eighty days with little to show for it. The summer has seen fierce fighting in a variety of sectors (to be enumerated below), but the contact line has shifted very little. I have been reluctant to publish a discussion of the Ukrainian campaign simply because they have continued to hold assets in reserve, and I did not want to post a premature commentary that went to press right before the Ukrainians showed some new trick or revealed a hidden ace up their sleeve. Sure enough, I wrote the bulk of this article last week, right before Ukraine launched yet another major attempt to force a breach in the Orikhiv sector.

At this point, however, the appearance of some of Ukraine’s last remaining premier brigades, which had previously been held in reserve, confirms that the axes of Ukraine’s attack are concretized. Only time will tell if these precious reserves manage to achieve a breach in the Russian lines, but enough time has passed that we can sketch out what exactly Ukraine has been trying to do, why, and why it has failed to this point.

Part of the problem with narrating the war in Ukraine is the positional and attritional nature of the fighting. People continue to look for bold operational maneuver to break the deadlock, but the reality seems to be that for now some combination of capability and reticence has turned this war into a positional struggle with a plodding offensive pace, which far more resembles the first world war than the second.

Ukraine had aspirations of breaking open this grinding front and reopening mobile operations – escaping the attritional struggle and driving on operationally meaningful targets – but these efforts have so far come to naught. For all the lofty boasts of demonstrating the superior art of maneuver, Ukraine still finds itself trapped in a siege, painfully trying to break open a calcified Russian position without success.

Ukraine may not be interested in a war of attrition, but attrition is certainly interested in Ukraine.

Ukraine’s Strategic Paradigm

For those that have been following the war closely, what follows will probably not be new information, but I think it is worth thinking holistically about Ukraine’s war and the factors that drive their strategic decision making.

For Ukraine, the conduct of the war is shaped by a variety of disturbing strategic asymmetries.

Some of these are obvious, like Russia’s much larger population and military industrial plant, or the fact that Russia’s war economy is indigenous, while Ukraine is entirely reliant on western deliveries of equipment and munitions. Russia can autonomously ramp up armaments production and there are abundant signs from the battlefield that the Russian war economy is beginning to find its groove, with new systems like the Lancet present in increasing abundance, and western sources now admitting that Russia has successfully serialized a domestic version of the Iranian Shahed Drone. Furthermore, Russia has the asymmetrical capacity to strike Ukrainian rear areas to an extent that Ukraine cannot reciprocate, even if they are given the dreaded ATACMs (these will give Ukraine the range to strike operational depth targets in the theater, but they can’t hit facilities in Moscow and Tula the way Russian missiles can strike anywhere in Ukraine).

With significant Russian asymmetries in population size, industrial capacity, strike capability, and – let us be blunt – sovereignty and decision-making freedom, an attritional-positional struggle is simply bad math for Ukraine, and yet that is precisely the sort of war in which it has become trapped.

What is important for us to understand, however, is that the strategic asymmetry goes beyond physical capacities like population base, industrial plant, and missile technology, and extends into the realm of strategic objectives and timelines.

Russia’s war has been deliberately framed in a fairly open-ended way, with goals largely tied to the idea of “demilitarizing” Ukraine. In fact, Russia’s territorial objectives remain rather nebulous beyond the 4 annexed oblasts (though it is safe to say that Moscow would like to acquire far more than just these). All that to say, Putin’s government has deliberately framed the war as a military-technical enterprise focused on destroying the Ukrainian armed forces, and has shown itself to be perfectly free to give up territory in the name of operational prudentia.

In contrast, Ukraine has maximalist goals that are explicitly territorial in nature. The Zelensky government has been open about the fact that it aims – however fanciful this may be – to restore the entirety of its 1991 territories, including not just the four mainland oblasts but also Crimea.

The confluence of these two factors – Ukrainian territorial maximalism combined with asymmetrical Russian advantages in a positional-attritional struggle – forces Ukraine to seek a way to break open the front and restore a state of operational fluidity. Remaining locked in a positional struggle is unworkable for Kiev, partially because Russia’s material advantages will inevitably shine through (in a fight between two big guys swinging big bats at each other, bet on the bigger guy with the bigger bat), and partially because a positional war (which amounts essentially to a massive siege) is simply not an efficient way to retake territory.

This leaves Ukraine with no choice but to unfreeze the front and try to restore mobile operations, with an eye towards creating some asymmetry of their own. The only feasible way to accomplish this is to launch an offensive aimed at severing critical lines of Russian communication and supply. Contrary to some suggestions that were popular this spring, a large Ukrainian offensive against Bakhmut or Donetsk simply did not fit the bill.

Frankly, there are only two suitable operational targets for Ukraine. One is Starobils’k – the beating heart at the center of Russia’s Lugansk front. Capturing or screening Svatove and then Starobils’k would create a genuine operational catastrophe for Russia in the north, with cascading effects all the way down to Bakhmut. The second possible target was the land bridge to Crimea, which could be cut by a thrust across lower Zaporizhia towards the Azov coast.

It was probably inevitable that Ukraine would select the Azov option, for a few reasons. The land bridge to Crimea is a more self-contained battlespace – an offensive in Lugansk would occur under the shadow of the Belgorod and Voronezh regions of Russia, making it relatively more difficult to put significant Russian forces out of supply. Perhaps even more significant, however, is Kiev’s complete obsession with Crimea and the Kerch Bridge – targets that hold hypnotic sway in a way that Starobils’k never could.

Again, this may sound like fairly intuitive review, but it’s worth contemplating how and why Ukraine ended up launching an offensive that was widely telegraphed and expected. There was no strategic surprise whatsoever – a definitely real video of GUR chief Budanov smirking didn’t fool anyone. The Russian armed forces certainly weren’t fooled, as they spent months saturating the front with minefields, trenches, firing emplacements, and obstacles. Everyone knew that Ukraine was going to attack toward the Azov Coast, specifically with an eye towards Tokmak and Melitopol, and that’s exactly what they did. A frontal attack against a prepared defense without the element of surprise is generally considered a poor choice, but here is Ukraine not only attempting such an attack but even launching it against a backdrop of global celebration and phantasmagorical expectations.

It’s impossible to make sense of this without understanding the way that Ukraine is shackled by a particular interpretation of the war to this point. Ukraine and its supporters point to two successes in 2022 where Ukraine was able to retake a substantial swathe of territory, in Kharkov and Kherson oblasts. The problem is that neither of these situations is portable to Zaporizhia.

In the case of the Kharkov offensive, Ukraine identified a sector of the Russian front that had been hollowed out and was defended only by a thin screening force. They were able to stage a force and achieve a measure of strategic surprise, due to the thick forests and general paucity of Russian ISR in the area. This is not to mitigate the scale of Ukraine’s success there; it was certainly the best uses of forces available to them and they did exploit a weak section of front. This success is hardly relevant to circumstances in the south today; mobilization has ameliorated Russia’s force generation problems so that they now longer have to make hard choices about what to defend, and the heavily fortified Zaporizhia frontline is nothing like the thinly held front in Kharkov.

The second case study – the Kherson counteroffensive – is even less germane. In this case, Ukrainian leadership is rewriting history in record time. The AFU banged its head on Russian defenses in Kherson for months throughout the summer and autumn last year and took atrocious losses. An entire grouping of AFU brigades was mauled in Kherson without achieving a breakthrough, and this even with Russian forces in a uniquely difficult operational disposition where they had their backs to a river. Kherson was only abandoned months later due to concerns that the Kakhovka dam might fail or be sabotaged (for those keeping score, it did in fact end up failing), and due to Russia’s need at the time to economize forces.

Again, this can easily be misconstrued as arguing that Russia’s withdrawal from Kherson did not matter. Obviously, abandoning a hard-earned bridgehead is a major setback, and retaking west-bank Kherson was a boon for Kiev. But we need to be honest about why it happened, and it plainly did not happen because of Ukraine’s summer counteroffensive – to underscore this, recall that Ukrainian officials openly wondered if the Russian withdrawal was a trick or a trap. The question is simply whether Ukraine’s Kherson offensive is predictive of future offensive success. It is not.

So, we have one case where Ukraine identified a lightly defended section of front and ran through it, and another where Russian troops abandoned a bridgehead due to logistical and force allocation concerns. Neither is particularly relevant to the situation on the Azov coast, and in fact an honest reflection of the AFU’s Kherson Counteroffensive might have given Ukraine second thoughts about a frontal assault on prepared Russian defenses.

Instead, Kharkov and Kherson have both been presented as proof positive that Ukraine can shatter Russian defenses in a straight up fight – in fact, we still have no examples from this war of the AFU defeating strongly held Russian positions, particularly post-mobilization when Russia finally began to resolve its manpower deficiencies. But Ukraine is caught in the grip of its own particular story about this war, which has imparted unearned confidence in its ability to conduct offensive operations. Tragically for mobilized Ukrainian Mykolas, this has dovetailed with a second swagger-producing mythology.

A major selling point for the Ukrainian counteroffensive has been the assessed superiority of the AFU’s big-ticket donations from the west – the main battle tanks and infantry fighting vehicles. Since the first deliveries were announced, there has been no shortage of boasting about the many superior qualities of western models like the Leopards and Challengers. The suggestion has essentially been that skilled Ukrainian tankers are only waiting to be unleashed once they get behind the wheel of superlative western builds. My personal favorite motif has been the practice of dismissing Russian tanks as “Soviet Era” – neglecting to note that the Abrams (designed 1975) and the Leopard 2 (1979) are also Cold War models.

It must be stated, again, that there is nothing wrong with western tanks. The Abrams and the Leopard are fine vehicles, but confidence in their game-changing capabilities stems from a mistaken assumption about the role of armor. It must be appreciated that tanks always have been and always will be mass-consumption items. Tanks blow up. They are disabled. They break down and are captured. Tank forces attrit – much faster than people expect. Given that the brigades prepared for Ukraine’s assault on the Zapo line were significantly understrength in vehicles, it was simply irrational to expect them to have an oversized impact. This is not to say that tanks aren’t important – armor remains critical to modern combat – but in a peer conflict one should always expect to lose armor at a steady clip, especially when the enemy retains fires superiority.

One can see, then how a measure of hubris can easily creep in to Ukrainian thinking, fueled by a healthy dose of desperation and strategic need. Reasoning from a distorted understanding of its successes in Kharkov and Kherson, emboldened by their shiny new toys, and guided by an overriding strategic animus that requires them to unlock the front somehow, the idea of a frontal attack without strategic surprise against a prepared defense really could seem like a good idea. Add in the good old fashioned trope about Russian incompetence and disorder, and you have all the recipes for an imprudent roll of the dice by Ukraine.

The Misfire

So now we come to the operational minutia. For a variety of reasons, Ukraine has chosen to attempt a frontal assault on Russia’s fortified Zaporizhia front, with the intention of breaching towards the sea of Azov. How can this be accomplished?

We had a few clues early on, accruing from a variety of geographic features and alleged intelligence leaks. In May, the Dreizin Report published what was purported to be a Russian synthesis of Ukraine’s OPORD (Operational Order). An OPORD functions as a broad sketch of an operation’s intended progression, and the document shared by Dreizin was billed as a summary of Russia’s expectation for Ukraine’s offensive (that is, it is not a leak of Ukraine’s internal planning documents, but a leak of Russia’s best guess at Ukraine’s plans).

In any case, in a vacuum it was anybody’s guess as to whether Dreizin’s OPORD was authentic, but we’ve subsequently been able to cross-check it. This is because of the other, even more infamous leak from earlier this spring, which included the Pentagon’s combat power build plan for Ukraine.

NATO was very generous and built Ukraine a mechanized strike package from scratch. However, because this mechanized force was cobbled together with a variety of different systems from all corners of the NATO Cinematic Universe, Ukraine formations are uniquely identifiable by their particular combination of vehicles and equipment. So, for example, the presence of Strykers, Marders, and Challengers indicates the presence of the 82nd Brigade in the field, and so forth.

Thus, despite Ukrainian pretensions of operational security, it’s actually been trivially easy for observers to know which Ukrainian formations are in the field. There have been a few deviations from the script – for example, the 47th Brigade was supposed to field the Frankenstein Slovenian M55 tanks, but in the end the decision was made to send the underpowered M55’s to the northern front and the 47th was deployed with a contingent of Leopard Tanks originally operated by the 33rd Brigade. But these are minor details, and on the whole we’ve had a good sense of when and where specific AFU formations get on the field.

Based on identifiable units, the Dreizin OPORD looks very close to what we actually saw at the onset of the Ukrainian offensive. The Dreizin OPORD called for an assault by the 47th and 65th Brigades on the Russian lines south or Orikhiv, in the sector bounded by Nesterianka and Novoprokopivka. Directly in the middle of this sector is the town of Robotyne, and sure enough that’s where the first big AFU assault came overnight on June 7-8, spearheaded by the 47th Brigade.

Now, from this point it becomes difficult to evaluate the Dreizin OPORD simply because Ukraine’s attack became instantaneously derailed, but one thing we can say is that Dreizin’s source was correct about the order that Ukrainian units would be introduced into battle. Based on this, we can flesh out the OPORD and feel pretty safe wagering that this is what the Ukrainians were hoping to achieve:

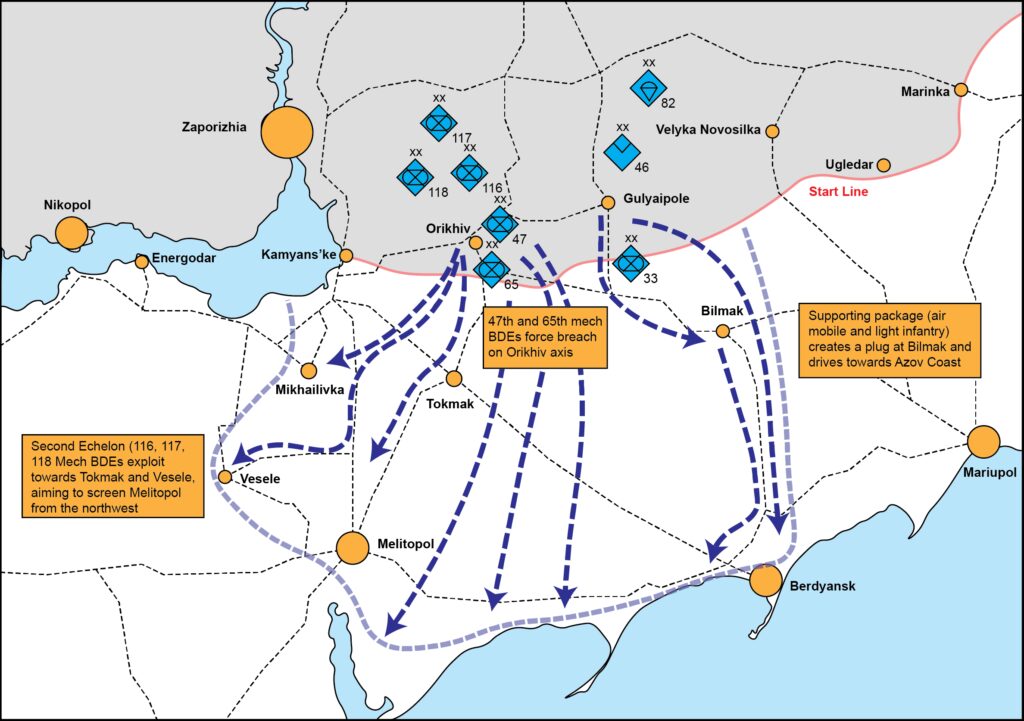

The intention seems to have been to force a breach in the Russian line using a concentrated armored assault by the 47th and 65th Brigades, after which a follow on force of the 116th, 117th, and 118th would begin the exploitation phase, driving for the Azov Coast and the towns of Mikhailivka and Vesele to the west. The objective was clearly not to get bogged down in urban fighting attempting to capture places like Tokmak, Berdyansk, or Melitopol, but to bypass them and cut them off by taking up blocking positions on the main roads.

Simultaneously, a lesser – but no less critical – thrust would come out of the Gulyaipole area and drive along the Bilmak axis. This would have the effect of both screening the main advance to the west and wedging the Russian front open, splintering the integrity of the Russian forces caught in the middle. Overall, this is a fairly sensible, if ambitious and uncreative plan. In many ways, this was really the only option.

So what went wrong? Well, conceptually it’s easy. There is no breach. The bulk of the maneuver scheme is dedicated to exploitation – reaching such and such a line, taking up this blocking position, masking that city, and so forth. But what happens when there’s no breach at all? How can such a catastrophe occur, and how can the operation be salvaged when it comes untracked in the opening phase?

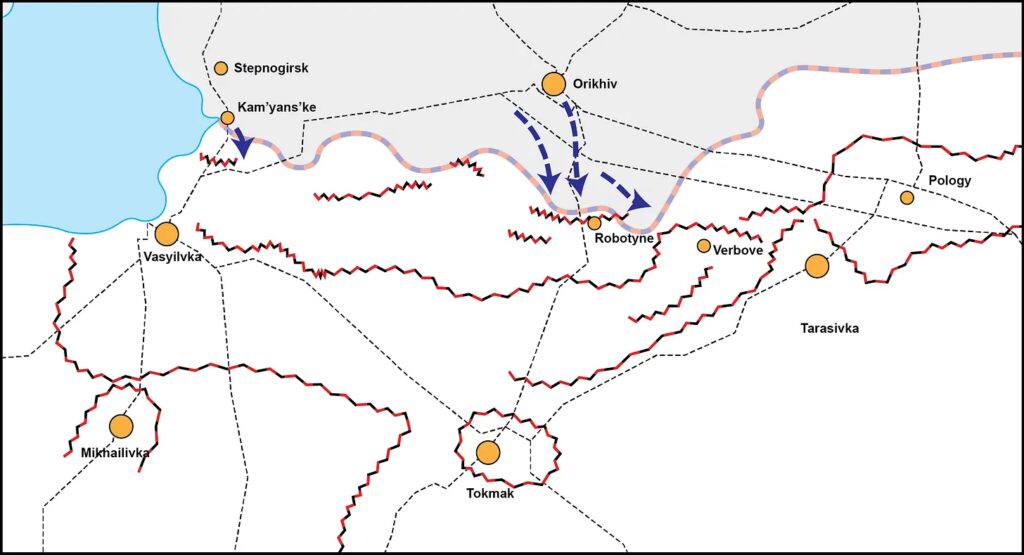

Indeed, this is precisely what has happened. Ukraine finds itself stuck on the edge of Russia’s outermost screening line, spending substantial resources trying to capture the small village of Robotyne, and/or bypass it to the east by infiltrating the gap between it and the neighboring village of Verbove. So instead of that rapid breach and turning maneuver towards Melitopol, we get something like this:

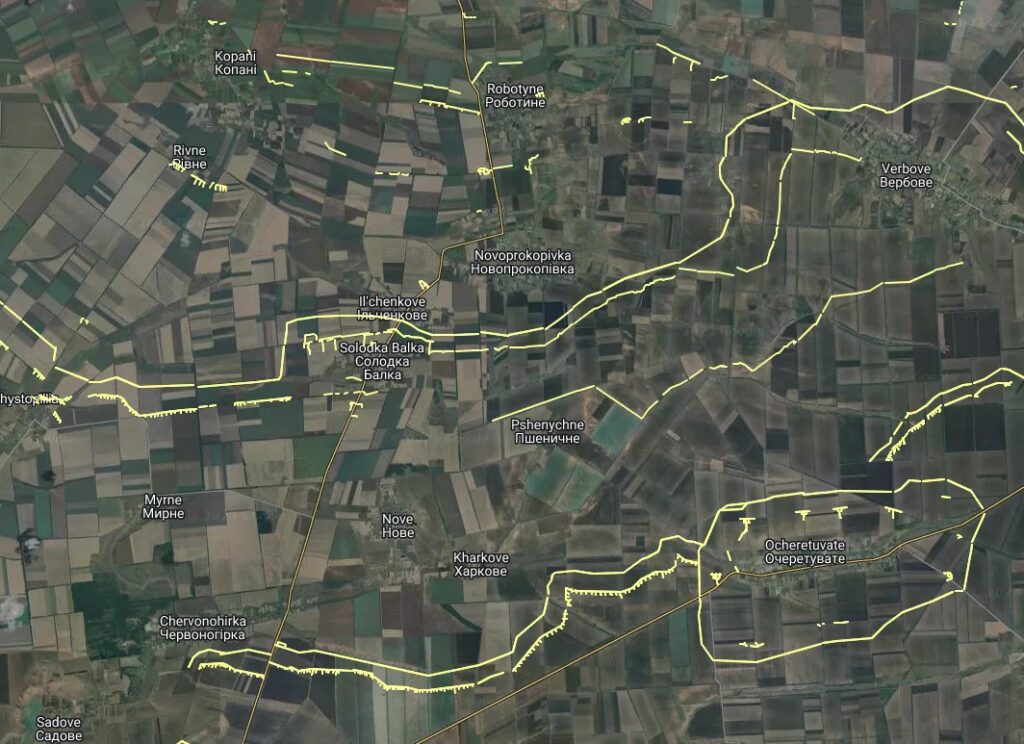

We could be generous and say that Robotyne is the last village before the Ukrainian attack reaches the main Russian defensive belt, but we’d be lying – they will also have to clear the larger town of Novoprokopivka, two kilometers to the south. Just for reference, here’s a closer look at the mapped Russian defenses in the battlespace, based on the excellent work of Brady Africk.

The discussion about these emplacements can get a little muddled, simply because it’s not always clear what is meant by that popular phrase “first line of defense.” Clearly there are some defensive works around and in Robotyne, and the Russians chose to fight for the village, so in some sense Robotyne is part of the “first line” – but it is more proper to speak of it as part of what we would call a “screening line”. The first line of continuous fortifications across the front is several kilometers further south, and this is the belt that Ukraine has yet to even reach, let alone breach.

As of this moment, it appears that Russian troops have lost total control of Robotyne but continue to hold the southern half of the village, while Ukrainian troops in the northern half of the village remain subject to heavy Russian shelling. We should probably at this point consider the village to be continuously contested and a feature of the gray zone.

Now, a quick note about Robotyne itself and why both sides are so determined to fight for it. It seems rather odd on the surface, given that the Russian preference in 2022 was to make tactical withdrawals under their fires umbrella. This time though, they are fiercely counterattacking to contest Robotyne. The value of the village lies not only in its location on the T-0408 Highway, but also its excellent perch on top of a ridge. Both Robotyne and Novoprokopivka lie on a ridge of elevated ground which is as much as 70 meters higher than the low-lying plain to the east.

What this means is fairly simple; if the AFU presses forward in attempts to bypass the Robotyne-Novoprokopivka position by pushing into the gap between Robotyne and Verbove, it will be vulnerable to fire on the flanks (particularly by ATGMs) by Russian troops on the high ground. We already have seen footage of this, with Ukrainian vehicles being taken in the flank by fire from Robotyne. I am highly skeptical that Ukraine can even attempt an earnest assault on the first defensive belt until they have captured both Robotyne and Novoprokopivka.

This would all be a tough nut to crack under ideal circumstances, with a variety of engineering problems to mediate, obstacles designed to funnel the attacker into firing lanes, perpendicular trenches to allow enfilade fire on advancing Ukrainian columns, and robust defenses on all the major roadways. But these are not the best of circumstances. This is a tired force that has exhausted much of its indigenous combat power, which is attempting to organize the attack using a piecemeal and understrength assault package.

Several factors conspired against the Ukrainian offensive, and synergistically they have created a bona fide military catastrophe for Kiev. Let us enumerate them.

Problem 1: The Hidden Defensive Layer

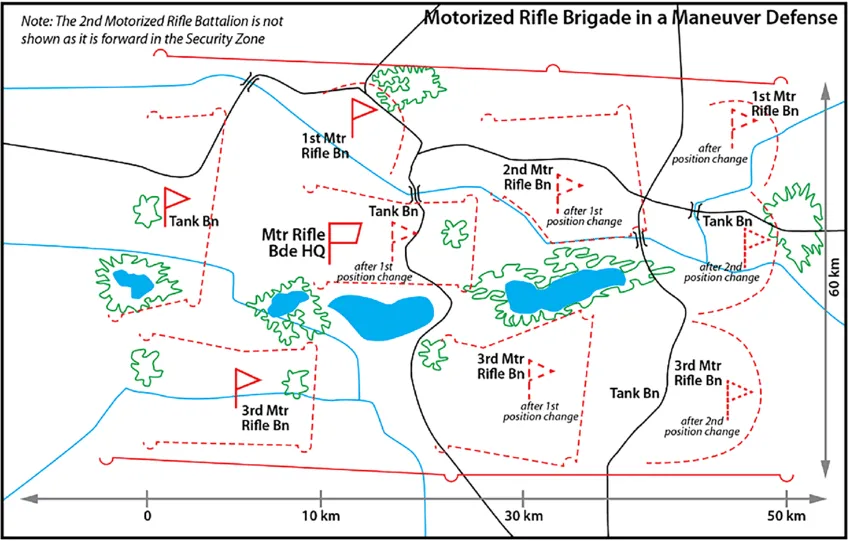

At this point, we need to acknowledge something that everybody missed about Russia’s defense. I previously expressed high confidence that Ukraine’s forces would be unable to breach the Russian defenses, but I mistakenly believed that the Russian defense would function according to the classic Soviet defense-in-depth principles (elucidated in great detail by the writings of David Glantz, for example).

Such a defense, put simply, is open to the idea that the enemy will breach the first or even second lines of defense. The purpose of the multilayered (or “echeloned” in the classic terminology) defense is to ensure that the enemy force gets stuck as it tries to break through. It may penetrate the first layer, but as it goes it is continually chewed up by the subsequent belts. The classic example is the Battle of Kursk, where powerful German panzers broke into the Soviet defensive belts but subsequently became stuck as they were ground down. You can think of this as being analogically similar to a Kevlar vest, which uses a web of fibers to stop projectiles: rather than bouncing off, the bullet is caught and its energy is absorbed by the layered fibers.

I was actually quite open to the idea that Ukraine would generate some penetration, but I anticipated them getting stuck in the subsequent belts and sputtering out.

What was missing from this picture – and this is a credit to Russian planning – was an unseen defensive belt forward of the proper trenches and fortifications. This forward belt consisted of extremely dense minefields and strongly held forward positions in the screening line, which the Russians evidently intended to fight for fiercely. Rather than breaking through the first belt and getting stuck in the interstitial areas, the Ukrainians have been repeatedly mauled in the security zone, and the Russians have consistently counterattacked to knock them back when they do manage to get footholds.

In other words, while we expected Russia to fight a defense in depth that absorbed the Ukrainian spearheads and shredded them in the heart of the defense, the Russians have actually shown a strong commitment to defending their forwardmost positions, of which Robotyne is the most famous.

On paper, Robotyne was expected to function as part of a so-called “crumple zone”, or “security zone” – a sort of lightly held buffer that puts the enemy through pre-registered fires before they bump into the first belt of continuous and strongly held defenses. Indeed, a variety of aerial and satellite surveys of the area taken before Ukraine went on the attack showed Robotyne laying well forward of the first solid and continuous Russian fortification belt.

What was missed, it seemed, was the extent to which the Russian defenders had mined the areas on the approach to Robotyne and were committed to defending within the security zone. The scale of the mining certainly seems to have surprised the Ukrainians, and creates a strain on Ukraine’s limited combat engineering capabilities. Even more importantly, the dense mines have created predictable avenues of approach for the Ukrainian forces, which force them to repeatedly run through the same gauntlet of fires and Russian standoff weaponry.

Problem 2: Insufficient Suppression

The signature image of the first great assaults on the Zapo Line has been columns of unsupported maneuver assets, being raked with Russian fires, both ground based (rocketry, ATGMs, and tube artillery) and from air platforms like the Ka-52 Alligator attack helicopter. One of the more startling aspects of these scenes was the way Ukrainian forces would come under heavy fire while still in their marching columns, taking losses before they ever deployed into firing lines to begin their assault proper.

There are myriad reasons for this. One is the now blasé issue of Ukrainian munition shortages. Consider the following items of interest. In the runup to Ukraine’s counteroffensive, Russia waged a heavy counter-preparatory air campaign that knocked out large AFU ammunition dumps. Ukraine’s initial assaults collapse in the face of heavy and unsuppressed Russian fires. The United States decides to transfer cluster munitions to Ukraine because, in the words of the president, “they’re running out of ammunition.” Add in the degradation of Ukrainian air defense, which allows Russian helicopters to operate with great effect along the contact line, and you have a recipe for disaster. Lacking the tubes to suppress Russian fires or the air defense to chase away Russian aircraft, the AFU opened their offensive by disastrously pushing forward unsupported maneuver elements into a hail of fire.

Problem 3: Russian Standoff Weapons

It’s crucial to understand that the Russian toolbox is fundamentally different than it was during the battle for Kherson last year, due to the rapidly expanding production of a variety of Russian standoff weapons – most notably the Lancet and the UMPK glide modifications for gravity bombs.

The Lancet in particular has been a star performer – there are claims that the trusty little loitering munition is responsible for nearly half of Russia’s artillery kills – and has filled a crucial capability gap that troubled the Russian army episodically throughout the first year of the war. Contrary to some western assessments that Russia simply could not manufacture drones in sufficient quantities, production of the Lancet has been successfully ramped up in a short period of time, and mass production of other systems like the Geran are coming online as well.

The proliferation of the Lancet and similar systems means, in a nutshell, that nothing within 30km of the contact line is safe, and this in turn disrupts the AFU’s deployment of critical support assets like air defense and engineering, magnifying their vulnerability to Russian mines and fires. In fact, we’ve increasingly seen Ukrainian artillery use decline in the Robotyne area due to the threat of lancets (they seem to be transferring tubes to other fronts), and the AFU is favoring the use of HIMARS in the suppressive role.

Problem 4: Repetitive Lines of Approach

Because the AFU failed to breach the Robotyne sector on their first attempt, they’ve been forced to continually move up additional units and resources to hammer on the position. This has particular implications, both in the sense that AFU forces must continually traverse the same lines of approach to contact, and in the fact that they are using the same rear area to assemble and stage their assault forces.

This makes the burden on Russian ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) significantly easier, since the AFU has no effective way to disperse or hide the assets that they are bringing forward to the assault. Staged Ukrainian forces and material have been hid repeatedly in the villages immediately behind Orikhiv, like Tavriiske and Omeln’yk, and Russia is able to strike rear area infrastructure like ammunition depots because – to put it simply – there are only so many places these these assets can be staged when you are repeatedly assaulting the same 20km wide sector of front.

We recently had Ukrainian Deputy Minister of Defense Hanna Malair complaining that the 82nd Brigade – newly deployed to the Orikhiv sector – had been hit with a series of Russian airstrikes in its staging areas. According to her, this was because of poor OPSEC revealing the brigade’s location to the Russians. But this really makes very little sense; the entire area of operations around Orikhiv is perhaps 25km deep (from Kopani to Tavriiske) and 20 km wide (from Kopani to Verbove). This is a small area that has seen a huge amount of military traffic along the same roads throughout the summer. The idea that Russia needs insider information to know that they ought to surveil and attack targets in this area is absurd.

Problem 5: Fragile Brigades

It actually takes significantly less damage to “destroy” an operational level unit than people think. A unit can become a combat scratch off at 30% losses (with some variance depending on how those are allocated). This is because when people hear the term “destruction”, they think that means total losses. Sometimes that’s how the word is used in colloquial conversation, but what matters for officers trying to manage an operation is whether or not a formation is combat capable of the tasks being asked of it – and those capabilities can vanish much more quickly than people realize.

This is particularly the case for the Ukrainian mech package, for a variety of reasons. For one, as we discussed in previous articles, these brigades started the fight well understrength (remember, for example, that the Ukrainian 82nd Brigade has only 90 Stryker AFVs, while an American Strkyer Brigade is supposed to have 300). Additionally, the cobbled together nature of these brigades – and the total lack of indigenous sustainment systems like repair and maintenance – means that the Ukrainians will naturally have to cannibalize these vehicles. They’ve already started designating “donor” vehicles that are written off completely to be stripped down for parts. The nexus of these two facts is that Ukraine’s mechanized brigades are understrength on vehicles to begin with, and will have an abysmally poor recovery rate, with hidden attrition behind the scenes due to cannibalization.

What this means is that when we heard admissions by mid-July that Ukraine had already lost 20% of its maneuver assets, there is an associated catastrophic decline in combat capability. The lead brigades – which chewed through 50% or more of their maneuver vehicles – can no longer shoulder combat tasks appropriate for a brigade, and the Ukrainians are forced to feed in their second echelon units prematurely.

At this point, partial elements of at least ten different brigades have been deployed in the Robotyne sector, with the 82nd likely to join them soon. Given that the NATO combat power build plan only included 9 NATO trained brigades, plus a few reconstituted Ukrainian formations, it’s safe to say that blooding all of them over a 71 day fight just to break into the screening line was not in the plan.

Staring at the Abyss

I’ve seen a variety of analysts and writers lately arguing that the insertion of additional Ukrainian units into the Robotyne sector signals the next phase of the operation.

This is nonsense. Ukraine is still mired in the first phase. What has happened is instead that the attrition of their first echelon brigades has forced them to commit their second (and third) wave to complete the tasks of the opening phase. The initial attack, led by the 47th Brigade, was intended to create a breach in the Russian screening line around Robotyne and advance to the main Russian belt further to the south. They failed, and the additional brigades earmarked for exploitation – the 116th, 117th, 118th, 82nd, 33rd, and more – are now being systematically fed in to keep the pressure on.

These brigades have not been destroyed, of course, simply because they are not being committed in their entirety, but rather as subunits. Nevertheless, at this point Ukrainian losses make up the better part of a whole brigade, distributed around the broader package, and over 300 maneuver elements (tanks, IFVs, APCs, etc) have been scratched off.

We need to say this very explicitly. Ukraine has not moved on to the next phase of their operation. They are stuck in the first phase, and have been forced to prematurely commit portions of the second echelon that was earmarked for later action. They are slowly but surely burning through the entire operational grouping, and so far they have not breached Russia’s screening line. The great counteroffensive is turning into a military catastrophe.

Now, this does not mean that the operation has failed, simply because it is still ongoing. History teaches us that it is unwise to make definitive pronouncements. Luck and human factors (bravery and intelligence, cowardice and stupidity) always have something to say. However, the trajectory is undeniably towards abject failure at the current moment.

So far, the AFU has shown some adaptability. In particular, we’ve recently seen them shift away from pushing forward unsupported columns of mechanized assets – instead they’ve been leaning on small dismounted units, trying to slowly push forward into the space between Robotyne and Verbove. The move towards dispersal is intended to reduce loss rates, but it also reduces the probability of a dramatic breakthrough even further and marks the temporary abandonment of decisive breaching action in favor of – once again – creeping positional warfare.

We would be remiss if we failed to note that there have been meaningful Russian losses in all of this. We know that the Russian forces in the Robotyne sector have required rotation and reinforcement, including with elite VDV and Naval Infantry units. Russia has taken counterbattery losses, it has lost vehicles in counterattacking action, and men have been killed holding their trenches. The initial assault groups that the Ukrainians threw in had a lot of combat power, and the fighting was very bloody for both sides. It’s not a one-sided shooting gallery, but a high intensity war.

But therein is the crux of the matter – Ukraine seems unable to escape the attritional and positional war that it finds itself in. It sounds all well and good to proclaim a return to “maneuver” warfare, but if there is an inability to breach enemy defenses, this is only an empty boast, and the nature of the struggle remains attritional. When the question becomes “will we breach before we run out of combat power”, you are not maneuvering. You are attriting.

In my series of articles on military history, we’ve looked at a variety of cases where armies tried desperately to unlock the front and restore a state of operational maneuver, but when there is no technical capacity to do so, these intentions do not matter one bit. Nobody wants to be trapped on the wrong side of attritional mathematics, but sometimes what you want does not matter at all. Sometimes attrition is imposed on you.

In the absence of the capabilities required to successfully breach Russia’s prodigious defenses – more ranged fires, more air defense, more ISR, more EW, more combat engineering, more more more – Ukraine is trapped in a rock fight. Two fighters are swinging bats at each other, and Russia is a bigger man with a bigger bat.

Two Bad Copes

Amid a clear misfire and growing strategic disappointment, two new suggestions have increasingly crept into the conversation – “copes”, if you will, that are utilized as a narrative comfort to explain why the Ukrainian operation is actually going just fine (despite nearly universal acknowledgment in the west that the results have been lackluster at best). I would like to briefly address each of these in turn.

Cope 1: “The first stage is the hardest”

You frequently see it argued that all the AFU has to do is break open the Russian screening line, and the remainder of the defenses will fall like dominos. The general thrust of this argument is that the Russians lack reserves and that the subsequent defensive lines are not adequately manned – just break open the first line, and the rest will fall apart.

This is probably a comforting thing to tell oneself, but it’s rather irrational. We could talk, for example, about Russia’s doctrinal schema for defense in depth, which prescribes liberal allocation of reserves at all depths of the defensive system, but it’s probably more fruitful to point at more immediate evidence.

Let us simply consider Russia’s behavior over the last six months. They have spent a tremendous amount of effort constructing echeloned defenses – are we really to believe that they did all this only to waste all their combat power fighting in front of these defenses? Nor is there any evidence that Russia is having trouble supplying the front with manpower at the present moment. We’ve seen continued rotations and redeployments amid an overall process of military enlargement in Russia. Indeed, of the two belligerents, it is Ukraine that seems to be scraping the barrel for manpower.

Cope 2: “Get within firing range”

This is the more fantastical story, and it represents a radical ad-hoc shift of the goalposts. The argument is that Ukraine doesn’t actually need to advance to the sea and physically cut the land bridge, all it has to do is get the Russian supply routes within firing range to cut off Russian troops. This theory has been advance liberally on Twitter X and by personalities like Peter Zeihan (a man who knows nothing about military affairs).

There are many problems with this line of thought, most of which stem from an inflated notion of “fire control.” To put it simply, being “in range” of artillery fire does not imply effective area denial or severed supply lines. If that were the case, Ukraine would be unable to attack out of Orikhiv at all, since the entire axis of approach is within Russian firing range. In Bakhmut, the AFU continued to fight long after their main supply routes came under Russian shelling.

The simple fact is that most military tasks are conducted within range of at least some of the enemy’s ranged fires, and the idea that Russia will collapse if the AFU manages to put a shell on the Azov coastal highway is fairly ridiculous. In fact, Russia’s main rail line is already within range of Ukrainian HIMARS, and the Ukrainians have successfully launched strikes on coastal cities like Berdyansk. Meanwhile, Russia strikes at Ukrainian sustainment infrastructure with regularity – yet neither army has collapsed yet. This is because ranged fires are a tool to improve attritional calculus and further operational goals – they do not magically win wars just by tagging the enemy’s supply roads.

Let’s be charitable though, and indulge this line of thinking. Suppose the Ukrainians managed to advance – not all the way to the coast, but far enough to bring Russia’s main supply routes within range of artillery. What would they do? Wheel up a battery of howitzers, park them at the very front line, and begin firing nonstop at the road? What do you think would happen to those howitzers? Counterbattery systems would surely set upon them. The idea that you can just haul up a big gun and start taking potshots at Russian supply trucks is really quite childish. Putting enemy forces out of supply has always required physically blocking transit, and that’s what Ukraine will have to do if they want to cut Russia’s land bridge.

The Distraction

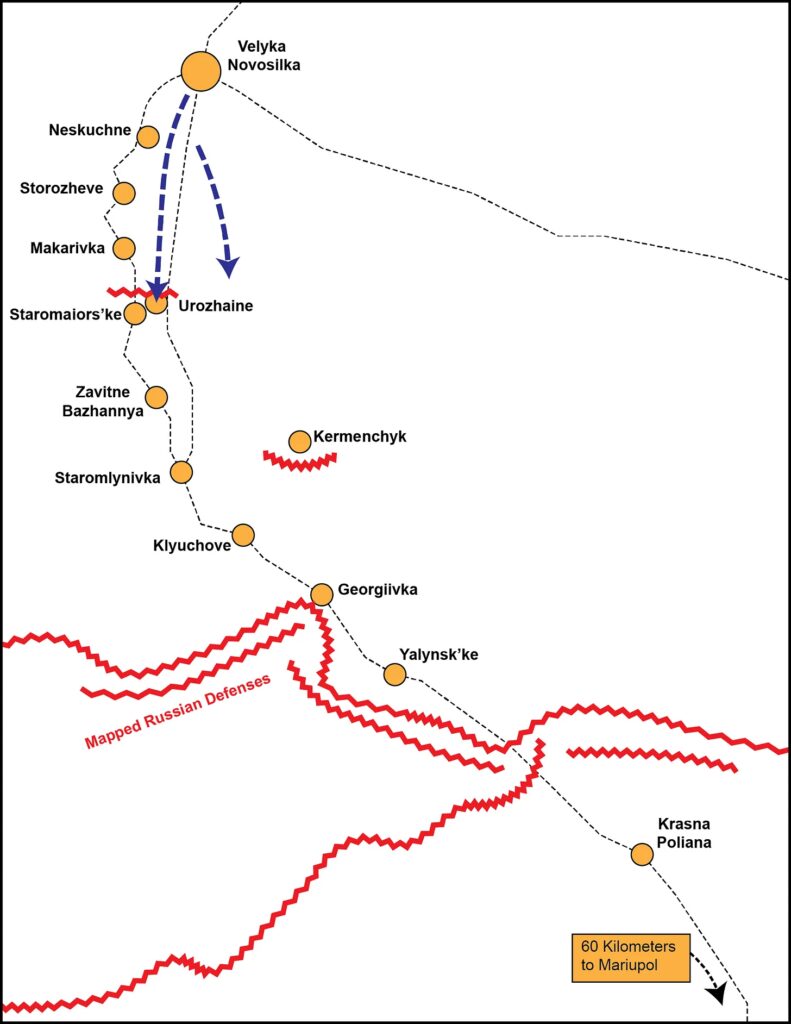

I am cognizant of the fact that I would be raked over the coals if I failed to discuss a secondary area of Ukrainian effort, farther to the east in Donestk oblast. Here, the Ukrainians have worked their way a good distance up the highway out of the town of Velyka Novosilka capturing several settlements.

The problem with this “other” Ukrainian attack is that it is, in a word, inconsequential. This axis of advance is operationally sterile in a very fundamental way, as it involves pushing groups up a narrow corridor of road that doesn’t lead anywhere important. As in the Robotyne sector, the AFU is still quite some distance from any of the serious Russian fortifications, and to make matters worse the road and settlements on this axis lay along a small river. Rivers, as we know, flow along the floor of the terrain, which means the roadway sits at the bottom of a wadis/embakement/glacis, choose your terminology. In fact, the road network as such consists of nothing except a single-lane roadway on either side of the river.

My reading of this axis is essentially that it was intended as a feint to create some semblance of operational confusion, but when the primary effort on the Orikhiv axis turned into a colossal misfire, the decision was made to continue to press here simply for narrative purposes. Ultimately, this is simply not an axis of advance that can exert a meaningful influence on the wider war. The forces deployed here are relatively miniscule in the grand scope of things, and they aren’t going anywhere important. Certainly, a thin, needlelike penetration is not going to drive more than 80 kilometers down a single lane road to the sea and win the war.

Conclusion: Finger Pointing

One of the surest signs that Ukraine’s counteroffensive has taken a cataclysmic turn is the way Kiev and Washington have already begun to blame each other, conducting a postmortem while the body is still warm. Zelensky has blamed the west for being too slow to deliver the requisite equipment and ammunition, arguing that unacceptable delays allowed the Russians to improve their defenses. This strikes me as rather obscene and ungrateful. NATO built Ukraine a new army from scratch in a process that already required greatly truncating the training times.

On the other hand, western experts have begun to blame Ukraine for supposedly being unable to adopt “combined arms warfare”. This is really a very nonsensical attempt to use jargon (incorrectly) to explain away problems. Combined arms simply means the integration and simultaneous use of various arms like armor, infantry, artillery, and air assets. Claiming that Ukraine and Russia are somehow cognitively or institutionally incapable of this is extremely silly. The Red Army had a complex and extremely thorough doctrine of combined arms operation. One professor at the US Arms School of Advanced Military Studies said: “The single most coherent core of theoretical writings on operational art is still found among the Soviet writers.” The idea that combined arms is some foreign and novel concept to Soviet officers (a caste that includes the Russian and Ukrainian high command) is ridiculous.

This issue is not some sort of Ukrainian doctrinal obstinacy, but a combination of structural factors rooted in the insufficiency of Ukrainian combat power and the changing face of warfare.

It’s frankly a little silly to say that Ukraine needs to learn about “combined arms” when they are very simply lacking important capabilities that would make a successful maneuver campaign possible – namely, adequate ranged fires, a functioning air force (and no, F-16’s will not fix this), engineering, and electronic warfare. The issue very fundamentally is not one of doctrinal flexibility, but of capability. By way of analogy, this is a bit like sending a boxer out to fight with a broken arm, and then critiquing his technique. The problem is not his technique – the problem is that he’s injured and materially weaker than his opponent. So too, the problem for Ukraine is not that they are incapable of coordinating arms, the problem is that their arms are shattered.

Secondly – and this, I admit, is rather shocking to me – western observers do not seem open to the possibility that the accuracy of modern ranged fires (be it Lancet drones, guided artillery shells, or GMLRS rockets) combined with the density of ISR systems may simply make it impossible to conduct sweeping mobile operations, except in very specific circumstances. When the enemy has the capacity to surveil staging areas, strike rear area infrastructure with cruise missiles and drones, precisely saturate approach lines with artillery fire, and soak the earth in mines, how exactly can it be possible to maneuver?

Combined arms and maneuver are predicated on the ability to rapidly concentrate enormous fighting power and attack with great violence at narrow points. This is probably impossible given the density of Russian surveillance, firepower, and the many obstacles they have put up to deny Ukrainian freedom of movement and scleroticize their activity. The main examples of maneuver in recent western memory – the campaigns in Iraq – have only tenuous relevance to circumstances in Zaporizhia.

Ultimately, we have returned to a war of mass – particularly massed ISR assets and fires. The only way Ukraine can maneuver the way they want is to break open the front, and they can only do this with more of everything – more mine clearing equipment, more shells and tubes, more rocketry, more armor. Only mass can crack open a suitable breach in the Russian lines. Otherwise, they are stuck in a positional creep through the dense Russian defenses, and criticizing them for being unable to grasp some sort of magical western notion of “combined arms” is the strangest sort of finger pointing.

So, whence goes the war from here? Well, the obvious question to ask is whether we believe Ukraine will ever have a more potent assault package than the one they started the summer with. The answer clearly seems to be no. It was like pulling teeth to scrape together these understrength brigades – the idea that, following on a defeat in the Battle of Zaporizhia, NATO will somehow put together a more powerful package seems like a stretch. More to the point, we have American officials saying fairly explicitly that this was the best mechanized package Ukraine was going to get.

It does not seem controversial to say that this was Ukraine’s best shot at some sort of genuine operational victory, which at this point seems to be slowly trickling away into modest but materially costly tactical advances. The ultimate implication of this is that Ukraine is unable to escape a war of industrial attrition, which is precisely the sort of war that it cannot win, due to all the asymmetries that we mentioned earlier.

In particular, however, Ukraine cannot win a positional-attritional war because of its own maximalist definition of “winning.” Since Kiev has insisted that it will not give up until it returns its 1991 borders, an inability to dislodge Russian forces poses a particularly nasty problem – Kiev will either need to admit defeat and acknowledge Russian control over the annexed areas, or it will continue to fight obstinately until it is a failed state with nothing left in the tank.

Trapped in a bat fight, with attempts to unlock the front with maneuver coming to naught, what Ukraine needs most is a much bigger bat. The alternative is a totalizing strategic disaster.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News