Abstract: This article explores what is known regarding the Islamic State’s leaders since the killing of the group’s second caliph Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi (conventionally dubbed “al-Mawla” for shorthand) in February 2022. In contrast with the group’s first caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the organization has publicized little information on his successors, who have released no audio messages of their own. Despite the fact that the group’s caliphs are now very much ‘men of the shadows,’ there is little evidence pointing to the prospect of the group’s fragmentation in Iraq, Syria, or elsewhere around the world, with the group’s affiliates seemingly willing to accept successor caliphs about whom little or nothing is publicly known.

On August 3, 2023, the Islamic State’s al-Furqan Media publicized a teaser announcement of a forthcoming speech by one “Abu Hudhayfa al-Ansari,” described as being the spokesman for the Islamic State. Considering that the previous spokesman was one “Abu Omar al-Muhajir” and the group had said nothing until then about his fate, it was predictable that the speech was going to announce that something had befallen its spokesman, and possibly its caliph as well.1 Sure enough, Abu Hudhayfa announced that the previous spokesman had been taken captive, and that the group’s caliph Abu al-Husayn al-Husayni al-Qurashi had been killed. He also announced that a new caliph—Abu Hafs al-Hashimi al-Qurashi—had been appointed in Abu al-Husayn’s place, continuing a line of faceless caliphs. Despite the fact that these caliphs are shrouded in a veil of obscurity, the group insists that its fighters and Muslims around the world declare allegiance to them.

What might now be called the ‘dark age’ of caliphs contrasts markedly with the public face of the group’s first caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. When the Islamic State first rose to global prominence in June 2014 with its seizure of territory spanning the borders of Iraq and Syria and the declaration of the caliphate under then leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, there was understandably much interest in the person leading the organization. Indeed, the Islamic State was keen to highlight a public face for its caliph, who had released audio messages prior to being named caliph and continued to do so during his tenure as caliph up to the time of his death in 2019. He also made two visual appearances: Once in a video released in July 2014 showing al-Baghdadi in the al-Nouri mosque in Mosul, and then an appearance in a video released in April 2019 following the end of the group’s territorial control in Iraq and Syria, showing him consulting with figures who were presumably part of the group’s top leadership.2

Moreover, Turki al-Binali, who essentially served as the Islamic State’s leading mufti in running the fatwa-issuing and research department that was created following the declaration of the caliphate, had written a pamphlet entitled “Stretch forth the hands to pledge allegiance to al-Baghdadi,”3 which included some biographical information about the would-be caliph, such as establishing his background in Islamic studies, his work as an imam and preacher in mosques in Iraq, his membership of the Majlis Shura al-Mujahidin (a predecessor group to the Islamic State of Iraq) and his leadership of the Shari‘i committees and judiciary in the Islamic State of Iraq prior to his appointment as leader of the Islamic State of Iraq in 2010.4

Thus, thanks to the high public profile of the Islamic State and its leader, widespread interest in the group and the available variety of sources of information, a fairly detailed picture of al-Baghdadi’s life and career inside the Islamic State emerged, despite some errors that gained prominence early on.a

Following al-Baghdadi’s death in October 2019 in a U.S. raid on his hideout in the area of Barisha in northern Idlib countryside, the group announced the appointment of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi as his successor, a move that was portrayed as being in accordance with al-Baghdadi’s “counsel,” implying that al-Baghdadi had recommended him to be his successor.5 While Abu Ibrahim made no speeches or public appearances during his tenure of around 28 months as caliph and the group has never given its own account of who he was, testimonies that emerged from Islamic State dissidents and defectors and Islamic State leaders in Iraqi detention correctly suggested that he was to be identified with Hajji Abdullah (al-Hajj Abdullah Qardash), who had served as a top deputy of al-Baghdadi and was known to intelligence services tracking the organization.6 As such, like al-Baghdadi, a good deal of information emerged as to who Abu Ibrahim was, including from interrogations while he had previously been in U.S. custody,7 and the identification of him with one “Amir Muhammad Sa ‘id Abd al-Rahman al-Salbi”b was essentially confirmed when President Biden announced that he had been killed in a U.S. raid in February 2022 and the organization then announced his death the following month.8

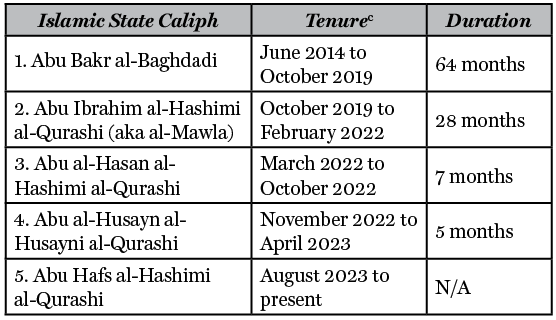

Table 1: The Islamic State’s Caliphs

The death of Abu Ibrahim, however, has essentially marked the end of the era of the group’s ‘known caliphs.’ Since his death, two successors have already been appointed and killed: namely, Abu al-Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi and Abu al-Husayn al-Husayni al-Qurashi, both of whom only lasted several months each and similarly made no public appearances and released no audio messages of their own. Moreover, the U.S. government has not come forward to affirm the identity of either of these figures, and the organization has had little to say about who they were.

This article explores in more depth what is known about these two successors to Abu Ibrahim and the circumstances surrounding their deaths, and considers the future of the organization in light of the seeming rapid rate at which the group’s caliphs are being eliminated.

Abu al-Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi

If there is one thing that can be ascertained with certainty regarding Abu al-Hasan’s identity, it is who he was definitely not. Shortly after the killing of Abu Ibrahim and prior to the announcement of Abu al-Hasan’s appointment, the journalist Hassan Hassan published an article for New Lines Magazine suggesting that the likely successor would be one Bashar Khattab Ghazal al-Sumaida’i.9 According to Hassan, al-Sumaida’i joined the Islamic State in 2013 and had previously been a member of the Iraqi jihadi group Ansar al-Islam, which is now largely confined to northwest Syria where it operates as a small independent faction under the watch of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). In addition, Hassan said that al-Sumaida’i served in a judicial capacity and had been close to Abu Ibrahim, though he had been based in Turkey for some time before returning to Syria in 2021.10

While this account of Sumaida’i was interesting, his supposed identity as Abu Ibrahim’s successor was never affirmed by U.S. intelligence, and doubts about the story began to emerge after Turkey arrested Sumaida’i in May 2022. Despite initial hype that Turkey had captured the Islamic State caliph,d Turkish authorities were subsequently unable to confirm that this figure was in fact Abu al-Hasan, but perhaps more importantly, the Islamic State released an editorial in its Al Naba newsletter in which the group mocked unspecified “analysts” for holding to fanciful wishes and hopes and trying to prove them to be true.11 The editorial gave as an example those who hoped that the caliph had been taken prisoner, and then added after mention of the caliph: “may God protect him.”12

The implication of these words was clear: Abu al-Hasan had not been taken prisoner by Turkey. If he had been taken prisoner, the group would likely have said so and either have launched a campaign to free him if it had believed that it was feasible to free him, or have simply appointed a successor, thus transferring the position of the caliph to another individual. This dual choice with regard to the fate of an imprisoned caliph derives from Islamic jurisprudence,13 and there is no reason to suppose the Islamic State would deviate from these norms with regards to its own caliphs.e

Doubts about the identification of Abu al-Hasan with al-Sumaida’i were further solidified by the surprise announcement by the Islamic State on November 30, 2022, about the death of Abu al-Hasan and the appointment of his successor Abu al-Husayn.14 The announcement came via an audio message of then spokesman Abu Omar al-Muhajir on al-Furqan Media, and said little about the precise circumstances of his death beyond the fact that Abu al-Hasan died a violent death through fighting the “enemies of God.”

Hours later, however, U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) released a statement claiming that Abu al-Hasan had been killed in mid-October 2022 in a clash with the “Free Syrian Army” in Syria’s southern province of Dar‘a, which is officially under Syrian government control.15 The CENTCOM statement did not capture the full nuance in that it was not the “Free Syrian Army” that killed Abu al-Hasan but rather, as will be outlined below, local militiamen, some of whom may have previously been part of the “Free Syrian Army”-brand insurgent groups that received backing from the United States, some European states, Jordan, and Gulf countries.16

An analysis by this author of local reports from the time suggests that Abu al-Hasan was likely killed during an offensive launched by local militiamen against Islamic State cells in the north Dar‘a countryside town of Jasim,17 a conclusion also reached by the United Nations.18 This offensive was backed by artillery support from the Syrian army, and only came about after the head of Syrian military intelligence in the province seriously threatened to storm the town if action was not taken in cooperation with government forces against Islamic State cells, whose presence was repeatedly doubted in pro-opposition activist media.19 It seems likely that neither the Syrian government nor the local militiamen were aware or certain that Abu al-Hasan had been killed during this offensive. Rather Arabic-language reports at the time only noted that an individual going by the names of “(Abu) Abd al-Rahman al-Iraqi” and “Sayf Baghdad” (“Sword of Baghdad”) had been killed.20 f While U.S. intelligence may have received some information at the time suggesting Abu al-Hasan had been killed, it probably could not verify the details and thus waited for the Islamic State’s own announcement for full confirmation.

Although the precise details of Abu al-Hasan’s apparent demise in the Jasim offensive have not been confirmed by the Islamic State, the group has nonetheless confirmed the broader point that Abu al-Hasan was killed in southern Syria fighting against forces that had backing from the Syrian government. In the announcement of Abu al-Husayn’s death, Abu Hudhayfa al-Ansari confirmed that Abu al-Hasan had been based in southern Syria, where he fought against the “Nusayris” (a derogatory term for Alawites, and thus referring to the Syrian government and its forces) and their “agents” (i.e. local militiamen working with the Syrian government) and was subsequently killed.21

All of these elements provide confirmation that Abu al-Hasan was not al-Sumaida‘i. In response to the growing doubts following the announcement of Abu al-Hasan’s death, Hassan and other defenders of the al-Sumaida’i theory suggested that Abu al-Hasan was originally al-Sumaida‘i but that the identity was transferred to another person following al-Sumaida‘i’s capture. There is little basis to accept this hypothesis. Indeed, the Islamic State implicitly mocked it in an editorial released after Abu al-Hasan’s death,22 stating that if the group had wanted, it could have continued using Abu al-Hasan’s name for the caliph after his demise, just as it could have continued using the name of the previous spokesman Abu Hamza al-Qurashi, the killing of whom had not been claimed by any side and was only revealed to the outside world via Abu Omar al-Muhajir in the announcement of the appointment of Abu al-Hasan as successor to Abu Ibrahim.23

Yet, the upshot of all the foregoing is simply to establish a negative: that Abu al-Hasan was not al-Sumaida‘i. Establishing this negative reveals virtually nothing about who Abu al-Hasan actually was. To date, there are only two other accounts as to who he might have been, with nothing to provide confirmation either way. One claim is that Abu al-Hasan was a brother of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi,24 while another account offered by the journalist Wa’il ‘Isam claims that Abu al-Hasan’s real name was Nour Karim Mutni, originally from the Albu ‘Ubayd tribe in Rawa in western Anbar.25

According to Wa’il’s account, Mutni’s career in jihadism began after his brother and some other relatives were killed in the al-‘Adhamiya neighborhood in Baghdad in 2005 by the “Wolf Brigade,” which was affiliated with the Interior Ministry and gained notoriety for sectarian violence against Sunnis.26 Initially working in logistical support, Mutni became involved in the administration of the Islamic State’s “Baghdad wilaya” (Baghdad province), and thus, according to Wa’il, acquired the nickname of “Sword of Baghdad,” which was one of the nicknames of an “(Abu) ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Iraqi,” killed during the Jasim offensive and has been identified with Abu al-Hasan. There is little information as to Mutni’s career in the Islamic State following his involvement in the administration of the Baghdad wilaya, except the claim in Wa’il’s reporting that he moved to the town of Albukamal on the border with Iraq in 2014.27

Abu al-Husayn al-Husayni al-Qurashi

The figure of Abu al-Husayn is even more obscure than his predecessor, Abu al-Hasan, though according to Voice of America, U.S. officials have claimed Abu al-Husayn was “not part of the group that founded IS [Islamic State] and is, instead, among the first of a new generation of leaders.”28 What precisely this means though is not clear: does it mean that Abu al-Husayn only joined after June 2014 when the caliphate was officially declared, or that he was not part of the generation of veterans going back to the days of the Islamic State’s predecessors such as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s al-Qa`ida in Iraq?

The announcement of his appointment might offer a slightly different picture. From that announcement, it can be inferred that he had probably not been recommended by his predecessor Abu al-Hasan, since no mention was made of implementing Abu al-Hasan’s counsel in the appointment of Abu al-Husayn. This is not to say that implementing the previous caliph’s counsel is necessarily required. Ultimately, the requirement for appointing a caliph is that the ‘people of binding and dissolution’ should come to an agreement through consultation on the appointment of a person who fulfils the various conditions required for a caliph (e.g., being of Qurashi lineage), and said person should be willing to accept the position. A predecessor’s recommendation can help in selecting the successor, but complying with the recommendation is not obligatory on those with the authority to appoint him. Thus, it may be that Abu al-Hasan recommended someone besides Abu al-Husayn and the group’s leadership chose not to go along with the recommendation, or perhaps Abu al-Hasan had not made any recommendation, which may be because he had not taken the time to consider the matter, or he did not think he could make a recommendation. Of course, it cannot be ruled out he did make the recommendation, but the Islamic State did not publicly reveal this fact in their announcement.

It can also be inferred that Abu al-Husayn was a veteran of some standing in the organization, as he was described as being among the “veterans of the mujahideen.” However, the group refused to say anything else about him, with then spokesman Abu Omar al-Muhajir affirming that “what you see from his deeds- if God wills- will suffice for you instead of mentioning his biography and deeds.”29 Clearly then, the organization felt that for security reasons, it could not disclose any detailed information about Abu al-Husayn’s identity, for fear that it might lead to the group’s enemies deducing his whereabouts and real identity. It may be that the group feared that revealing too much about his background might have allowed for intelligence agencies—especially U.S. intelligence—to identify him as someone they held derogatory information on, an issue that came to light with al-Baghdadi’s successor, Abu Ibrahim, and his interrogation files.30 This may explain why the Islamic State said virtually nothing about Abu Ibrahim’s background when he became caliph.

Until now, no account has emerged as to what Abu al-Husayn’s real name might have been. An account active on the social media site TamTam and entitled “Channel to expose the servants of al-Baghdadi and al-Hashimi,” which provided advance notification on the deaths of Abu al-Hasan and Abu al-Husayn prior to their being announced on al-Furqan Media, suggests that Abu al-Husayn must have been Iraqi. The account claimed in a post in January 2023 that the figure of Abd al-Raouf al-Muhajir (aka Abu Sara al-Iraqi),31 who (according to this same account) occupied the position of head of the office for the administration of the wilayat at the time32 and was subsequently killed, was in control of the group’s Majlis Shura (consultation council) and thus controlled the appointments of the caliph, and he supposedly would not allow non-Iraqis to hold the position of caliph.33

The first claim of the killing of Abu al-Husayn emerged on April 30, 2023, when Turkey’s president Erdogan announced that Abu al-Husayn had been killed in an operation conducted by Turkish intelligence, which had supposedly discovered that he was present in the area of Jindiris in the Afrin region of Aleppo province and that he was planning to change location.34 On April 29, the Turkish intelligence launched an operation targeting his supposed safehouse, which consisted of multiple stories and had a concealed underground bunker, and called on him to surrender. With no response received, the house was raided and the individual inside allegedly blew himself up.35

The Turkish media reports offered no biographical details on Abu al-Husayn apart from saying that he had joined the group in 2013.36 The same claim of joining in 2013 had been made in Hassan Hassan’s account of who Abu al-Husayn’s predecessor Abu al-Hasan was.37 It is possible that this alleged detail regarding Abu al-Husayn’s career is a coincidence, but perhaps it was mistakenly lifted by Turkish media from Hassan Hassan’s account of Abu al-Hasan. The Turks subsequently identified the deceased individual as a Syrian-born individual, holding the alias of Abdul-Latif, but U.N. member states were not able to confirm the dead man was the Islamic State leader, with some sceptical that a non-Iraqi would have been leading the group.g For its part, the United States did not provide a confirmation of the Turkish claims, indicating the extent of the U.S. uncertainty about Abu al-Husayn’s identity.38

It was not until some three months later that the Islamic State commented on the matter, releasing Abu Hudhayfa al-Ansari’s speech announcing the death of Abu al-Husayn and the appointment of Abu Hafs as his successor.39 This time, specific details were offered as to the circumstances of Abu al-Husayn’s death, aimed at refuting the “Turkish theatrics” publicized in media. By the group’s own account, rather than being killed by Turkish intelligence, Abu al-Husayn was supposedly killed in a confrontation with “the Hay’a of apostasy and collaboration, the agents of the Turkish intelligence agencies, in one of the localities of Idlib countryside.” The reference here is to HTS, which evolved out of the al-Qa‘ida affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra and has developed a working relationship with Turkey in northwest Syria,40 effectively enforcing a freeze on the military frontlines between the Syrian government and the insurgent groups in the region since the ceasefire negotiated between Turkey and Russia in spring 2020. HTS has also gone after Islamic State cells in the region for years.41

According to the Islamic State, following Abu al-Husayn’s death, HTS handed over his body to the Turkish government, allowing Erdogan to use Abu al-Husayn’s killing to bolster his chances of re-election. Yet, in response to Abu Hudhayfa’s speech, the spokesman for the “General Security Service” (GSS), which is nominally independent but is in fact affiliated with HTS, denied that the GSS had killed Abu al-Husayn and handed him over to Turkey, affirming on August 4, 2023, that if they had in fact killed him, they would have declared so publicly.42

The conflicting claims raise the obvious question as to which account should be believed: Turkey’s claim to have killed Abu al-Husayn in an operation in Jindiris, or the Islamic State’s claim that HTS killed him and then handed his body over to Turkey. On balance, the Islamic State’s account seems more credible, though the Turkish account cannot be definitively excluded as of the time of publication. The reason for lending the Islamic State’s account more credibility is simply the fact that the group has less motive to mislead people on the matter. There would be no shame or loss for the group to admit that its leader had been killed at the hands of Turkish intelligence as opposed to HTS. After all, both entities are seen as “apostates” by the Islamic State, and it is considered an honor for the caliph to die fighting these supposed enemies of God.

In contrast, if the Islamic State’s account of events is correct, then it can be seen as constituting a source of embarrassment for Turkey, whose actions can be interpreted as cooperating with HTS on combating the Islamic State, despite the fact that HTS is designated as a terrorist organization by Turkey.h For HTS, there is a motive for the group to have cooperated with Turkey in handing over his body and potentially bolstering Erdogan’s chances at re-election, for the Turkish elections were characterized by increasing talk, especially from the opposition to Erdogan, about the prospect of normalization of relations with the Syrian government—a development, which, if actually realized, would have negative implications for the future of the HTS-controlled enclave in northwest Syria.

Thus, for HTS, if it handed over Abu al-Husayn’s body to Turkey, that would have had the advantage of bolstering the group’s status as a security partner against terrorism and instability in the eyes of the counterterrorism community, and the advantage of bolstering the chances for the re-election of Erdogan, who was less inclined toward normalization of relations with the Syrian government. In other words, if HTS’ actions were such as claimed by Islamic State spokesman Abu Hudhayfa, they would fit in rationally with HTS’ long-term strategic goal of preserving its enclave in northwest Syria through cementing its partnership with Turkey in the region. It can also be seen why HTS may have wanted to keep silent about the matter and then deny any involvement: The behavior could be interpreted as working with a Western ally/NATO member against other Muslims, and interpreted as electioneering for Erdogan, whereas HTS continues to reject the practice of democracy in its areas of control.43

It is possible that the Turkish raid on the house in Jindiris took out an individual who was another high-ranking member of the Islamic State, and it is also possible that HTS may not have realized that it had killed Abu al-Husayn but had handed over his body to Turkey as he was suspected of being a high-rank member of the Islamic State and so HTS decided to allow Turkey to verify his identity. It must be acknowledged however that no definitive account exists yet for the demise of Abu al-Husayn.

The Appointment of Abu Hafs al-Hashimi al-Qurashi and the Future of the Islamic State

As already outlined, the same speech announcing the death of Abu al-Husayn also announced his successor as one Abu Hafs al-Hashimi al-Qurashi. Here, too, as with Abu al-Husayn’s appointment, no mention was made of implementing the predecessor’s “counsel” in Abu Hafs’ elevation to the caliphate. Rather, it is only said that the “people of binding and dissolution” (those with the authority to appoint a new caliph) in the Majlis Shura “came together, deliberated, consulted and mutually agreed on appointing” him, suggesting that no recommendation had been made by Abu al-Husayn as to the appointment of a successor. The speech had little specific detail about Abu Hafs’ biography other than to suggest he is a veteran of the Islamic State who has lived through the group’s lowest fortunes, as he has been “bolstered by adversities, and made experienced by severe trials of fate,” with a track record of fighting the “Crusaders and apostates.”44

Some of the initial analysis of the speech has focused on its elaboration of the obligation to pledge allegiance to the caliph and its citations of the medieval authorities of Imam al-Mazari (d. 1141 CE) and Imam al-Nawawi (d. 1277 CE) on the conditions for the validity of the allegiance to the imam (in other words, to the caliph). Specifically, M. Nureddin of the Arabic-language channel al-Aan, which provides extensive coverage of jihadi groups and likes to highlight internal problems and disagreements within them, has suggested that the citation of al-Nawawi in particular hints at internal disagreements within the group on the appointment of Abu Hafs.45

Yet, there is no compelling reason to think this is the case. The same speech in fact emphasizes that the “people of binding and dissolution” in the group’s Majlis Shura mutually agreed on appointing Abu Hafs. The same process of the coming together, consultation, and mutual agreement between them was highlighted in the speech on Abu al-Husayn’s appointment. While it is true that the citation of al-Nawawi in Abu Hudhayfa’s speech states that not all the people of binding and dissolution have to give allegiance to an imam for that allegiance to be valid, in this author’s assessment that was not the main point behind the Islamic State’s citation of him. Rather, as with the citation of al-Mazari, the common thread is to emphasize that not everyone has to come and profess allegiance to the caliph in person for that allegiance to be valid, thus justifying the validity of allegiance to the Islamic State’s leader while he remains behind a veil of obscurity for security reasons.

Insofar as there is any significance behind citing al-Nawawi for the notion that not all the people of binding and dissolution have to give allegiance for it to be valid, it is only to say that the mutual agreement of the people of binding and dissolution in the Islamic State’s Majlis Shura was sufficient for Abu Hafs to be made caliph and for allegiance to him to be valid. In this context, it should also be noted that when al-Binali wrote his pamphlet on the validity of allegiance to al-Baghdadi, he too emphasized that not all the people of binding and dissolution had to give allegiance for it to be valid, but only those of them who could, and he cited the same excerpt from al-Nawawi.46

The primary takeaway from the Islamic State’s loss of two of its caliphs within the span of months is that the security environment of ‘Islamic State Central’ in Iraq and Syria is currently a difficult one for the group’s top leadership to operate in. The group has no meaningful control of territory, and the military forces and security apparatuses of its enemies are constantly on the lookout for Islamic State cells, and in the process, they may even kill the caliph or other top leaders of the Islamic State without fully realizing who they actually are. Despite these difficulties facing ‘Islamic State Central,’ it seems unlikely that Abu Hafs or whoever succeeds him upon his death will relocate outside of the Iraq-Syria area. Indeed, among the Islamic State’s fighters whom Abu Hudhayfa urged to continue the fight, the new spokesman addressed the “soldiers of the abode of the Caliphate in Iraq and al-Sham,”47 suggesting that Iraq and Syria remain ‘Islamic State Central,’ despite the collapse of the territorial caliphate there and the far greater success now enjoyed by affiliates in the Sahel and West Africa.i

While the Islamic State may not have a large supply of people who could fill the position of caliph, the group’s fighters around the world seem willing for now to accept the idea of a ‘caliph of the shadows’ and the validity of allegiance to him, something emphasized in the group’s propaganda highlighting allegiance pledges from around the world to Abu Hafs,48 just as was the case with Abu al-Husayn and before him, Abu al-Hasan. The group has also sought to counter the idea that the repeated loss of the caliph somehow makes the Islamic State’s caliphate invalid, stressing for comparison the short terms of the Rashidun caliphs who immediately succeeded Muhammad and whom the Islamic State seeks to emulate, while also noting that three of them (‘Umar, ‘Uthman, and ‘Ali) met violent deaths.49

Meanwhile, the threat from the group remains. As noted by the United Nations in a July 2023 report, “despite significant attrition of the ISIL (Da’esh) leadership in Iraq and the Levant, the group remains resilient and the risk of resurgence should counter-terrorist pressure ease is real.”50 According to the same report, “the role of the overall leader has become less relevant to the group’s functioning.”51

In short, the Islamic State is still weathering the storm facing its central leadership, and one should be cautious about hopes for the group’s imminent demise with the loss of Abu al-Husayn.

Substantive Notes

[a] For example, one early story claimed that al-Baghdadi was in U.S. custody until 2009 and supposedly told his captors that he would see them “in New York.” U.S. officials speaking to the media quickly cast doubt on this story. See, for example, “ISIS Leader’s Ominous New York Message in Doubt, But US Still on Edge,” ABC News, June 16, 2014. Moreover, prison records reviewed by this author show that al-Baghdadi was released from custody by the end of 2004. For detail that aligns with this chronology, see Daniel Milton and Muhammad al-`Ubaydi, “Stepping Out from the Shadows: The Interrogation of the Islamic State’s Future Caliph,” CTC Sentinel 13:9 (2020).

Citations

[1] “So rejoice in your transaction you have contracted,” al-Furqan Media, August 3, 2023.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News