The fall of the Nagorno-Karabakh government after 30 years could empower Turkey and weaken Iran.

The convoys snaked for miles along mountain passes as the mass exodus of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh, a majority Armenian enclave that is formally part of Azerbaijan, continued to unfold. Western leaders wrung their hands but did nothing to stop it. With the few belongings they could retrieve — mattresses, refrigerators, pots and pans — piled precariously on their battered Soviet-era cars, over 100,000 people, almost triple the population of Lichtenstein, fled the contested region where Armenians dwelled for millennia until Azerbaijan first starved them under a nine-month-long blockade then attacked them on Sept. 19 in what it called an “anti-terror operation.”

The effective ethnic cleansing of an entire population in less than two weeks marked one of the largest civilian displacements in the South Caucasus since the collapse of the Soviet Union and a geopolitical shift of seismic proportions that empowers Turkey, weakens Iran and puts Armenia’s fledgling democracy at risk. For most Armenians, it was — as Armenian political analyst Tigran Grigoryan put it — “the greatest catastrophe to befall our people since the genocide of the Ottoman Armenians in 1915.” Yet the story has already vanished from international headlines.

By Sunday, when Western media and aid organizations were finally allowed into Stepanakert, the region’s capital, practically all of Nagorno-Karabakh’s estimated 120,000 Armenians had left. The clutch of the elderly and disabled who remained acknowledged they had not been “forced” to leave by Azerbaijani authorities.

On paper, it is true. Azerbaijan did not order any Armenians to leave. Lest there be any doubt, Baku’s well-oiled propaganda machine flooded social media with pictures of Azerbaijani forces handing chocolates to the very same children it deprived of the most basic foodstuffs for months as they crossed into Armenia. Yet it ensured that life was so miserable that few would opt to stay. Indeed, even as Azerbaijani authorities rebuffed claims of ethnic cleansing, insisting their forces had struck “legitimate military targets,” eyewitness accounts of rape and indiscriminate shelling that wounded and killed children began to emerge.

“There are grounds to believe that war crimes occurred in four villages — Taghavard, Haterk, Vardadzor and Kyulagagh — on the first day of the assault,” said Eric Hacopian, who is affiliated with the Civilitas Foundation, an independent nonprofit based in the Armenian capital, Yerevan. “But survivors are too scared to talk,” Hacopian told Al-Monitor. The International Committee of the Red Cross has begun investigating reports that hundreds of civilians, many of them children, remain missing.

Azerbaijan showed few signs of contrition as it named a street in Stepanakert on Tuesday after Enver Pasha, the Young Turk leader who is seen as one of the main architects of the Armenian genocide.

Outside a government registration center for refugees in Goris, a mountain valley close to the Lachin corridor linking Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, a sea of men, women and children clutched their belongings, looking exhausted and dazed. An old woman lay slumped in a rickety wheelchair.

Teenage volunteers pressed water bottles into the refugees’ hands while others handed out used clothing. Inside a tent pitched by the UN’s World Food Program, refugees wolfed down bowls of chicken soup. “Join us for the next course: borsch,” said Movses Poghosyan, director of the local charity House of Hope, his voice seesawing between hilarity and grief.

“We were hiding in the basement without food and water for three days. The shelling was so loud. We were terrified; the children cried nonstop,” said Vera Antonyan, a mother of four, as she cradled her 7-month-old daughter Gabriella, who was born during the blockade. The family had just arrived from Stepanakert after a 14-hour drive. “For months I could not find food for my baby, and now this,” Antonyan lamented, as her mother-in-law, Marine Karapetyan, who worked as a cleaning lady in a children’s hospital, broke down in tears.

Nineteen-year-old Maria Arakelyan — an aspiring dressmaker from the village of Karmishuka who appeared so malnourished that she looked 12 — tried to put a brave face on her plight. “We will return,” she said, gesturing to her three siblings. Her father, Artyom, who grew vegetables for a living, angrily interjected. “I left my boy’s grave there,” he said of his son who had died fighting in the previous war in 2020 in which Azerbaijan wrested back territories occupied by Armenia in the early 1990s together with parts of Nagorno-Karabakh. “It’s all Pashinyan’s fault. Next, he will give them Yerevan.”

Armenian roulette

Nikol Pashinyan, the Armenian prime minister and a former journalist, led the mass protests in 2018 that dislodged the latest Kremlin-backed kleptocrat, Serzh Sargsyan, who had kept the country mired in poverty and repression. Armenia’s first retail politician has since been waging war against the old elites and modernizing the country with shiny new roads and hospitals. Per capita income doubled as IT startups boomed. Yerevan, once a gloomy post-Soviet backwater, brims with life. A crimson Ferrari crawled along Pushkin Avenue on a recent evening as designer-clad Armenians sipped cocktails in posh sidewalk cafes. The capital is ringed with new high rises boasting views of Mount Ararat across the border in Turkey. The influx of young Russian professionals following the invasion of Ukraine has given the economy a further boost.

Pashinyan was so popular that he was reelected in 2021 despite Armenia’s crushing defeat by Azerbaijan in the 44-day-long war the year prior. Over 3,800 Armenian soldiers died, an unbearably high toll for a country of 2.9 million with a declining birthrate.

Pashinyan’s efforts to move Armenia away from Russia to the West raised hopes that the country would grow irrevocably prosperous and democratic. For Pashinyan, this involved several risky moves. Under a peace deal brokered by Russia in November 2020, Armenia formally renounced all claims to Nagorno-Karabakh, which is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan. It demanded, however, that the ethnic rights of its majority Armenians who ran a de facto state there called Artsakh for the past 30 years be guaranteed.

Azerbaijan has rejected Nagorno-Karabakh’s demands for autonomy and, with no Armenians left, the point is now moot.

Pashinyan also reached out to Armenia’s historic tormentor, Turkey, whose killer drones and military advisers clinched Baku’s 2020 victory and whose Ottoman forebears murdered over a million Armenians in what is acknowledged by numerous countries, including the United States, as genocide. The “normalization process” was meant to result in the establishment of diplomatic relations with Ankara and the reopening of land borders sealed by Turkey during the first Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, during which Armenia and Azerbaijan committed war crimes and acts of ethnic and cultural erasure. However, a vanquished Azerbaijan “undoubtedly came off worse,” according to Thomas de Waal, the author of “Black Garden,” a historical account of that conflict.

Russia’s setbacks in Ukraine further emboldened Pashinyan. He has deepened security ties with the United States. Armenia held joint military exercises with US forces even as fighting erupted in Nagorno-Karabakh. “There is a lot more going on behind the scenes,” said a senior Armenian official speaking anonymously to Al-Monitor. The official declined to elaborate.

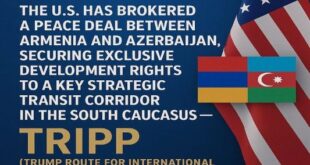

Since November, in a further bid to sideline Russia, Secretary of State Antony Blinken hosted three rounds of peace talks with the foreign ministers of Armenia and Azerbaijan while cheering on Ankara’s engagement with Yerevan.

In May, Pashinyan hinted that he might pull out of the Collective Security Treaty Organization, Russia’s version of NATO. In early September, his wife, Anna, traveled to Ukraine to deliver humanitarian aid for the first time since the war began. Photos of her posing with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his spouse, Olena, will not have amused Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

In a further escalation, Armenia’s parliament voted Tuesday to join the International Criminal Court, a move described by Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov as “extremely hostile.” Countries that have signed and ratified the Rome Statute that created the ICC are bound to arrest Putin, who was indicted for war crimes in Ukraine if he sets foot on their soil.

The same day, French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna said Paris had agreed to a deal to supply French hardware to the Armenian military.

Can Pashinyan’s gamble pay off?

Red lines breached

During a Sept. 14 hearing at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Acting Assistant Secretary of State for Europe and Eurasian Affairs Yuri Kim suggested it had. She noted that Blinken’s “leadership has yielded results” and that Armenia and Azerbaijan had made “progress on a peace agreement that could stabilize the region.” Kim warned, however, that the United States “will not countenance any action or effort — short term or long term — to ethnically cleanse or commit other atrocities against the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh. … We have also made it abundantly clear that the use of force is not acceptable. We give this committee our assurance that these principles will continue to guide our efforts in this region.” Five days later, Azerbaijan attacked Nagorno-Karabakh.

Kim and Samantha Power, the USAID administrator and author of a book pressing for recognition of the Armenian genocide, rushed to Yerevan the following day. The largely symbolic visit did nothing to change the facts on the ground. On Sept. 26, the leaders of the Republic of Artsakh formally surrendered, ending their decades-long quest for independence as Armenians continued to pour out of the enclave.

EU leaders have since aired anger at Azerbaijan’s “betrayal.” Yet Azerbaijan has not faced any sanctions and there are few signs that it will. The Europeans have grown more dependent on the energy-rich state since the war on Ukraine led to sanctions on Russian oil and gas sales. In 2022, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen flew to Baku where she hailed Azerbaijan as a “trustworthy partner” and struck a deal to double EU imports of Azerbaijani gas by 2027. On Tuesday, European Council President Charles Michel said he was “disappointed” with Azerbaijan and that it needed to show “goodwill” and respect international law to “protect the entire population of Azerbaijan, including the Armenian population,” never mind that there are virtually no Armenians left inside Azerbaijani territory. Still, Azerbaijan remained “a partner,” he intoned.

The framing of the Nagorno-Karabakh tragedy as a humanitarian crisis is already in full swing. “Western governments will send aid to clear their consciences and go back to business as usual,” the senior Armenian official observed.

Bye Bye, Russia?

Cynics might argue that it’s all for the best. Now that the Nagorno-Karabakh issue has been “resolved,” there is no longer a need for an estimated 2,000 Russian peacekeepers deployed in the enclave under the 2020 cease-fire accord.

“Destroying the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic eliminates the main obstacle to Armenian-Azerbaijani peace and allows Armenia to tell the Russians to go,” said Benjamin Poghosyan, who heads the Center for Political and Economic Strategic Studies in Yerevan. The same applies to peace between Turkey and Armenia. Russian border forces stationed along the border to defend Armenia would no longer be necessary. “From the US perspective, this is a win-win,” Poghosyan told Al-Monitor.

Many Armenians might welcome a Russian withdrawal amid widespread fury over the Kremlin’s perceived support for Azerbaijan and Putin’s cozy ties with its strongman, Ilham Aliyev. In the 2020 conflict, Russia sat on its hands as Azerbaijani forces clobbered their Armenian foes. In the latest round, its peacekeepers stood by as Azerbaijani forces overran Nagorno-Karabakh. “Russia is responsible from the very beginning. Russia proved it is not a trustworthy partner,” said a man who would only identify himself as “Styopa” and sells paintings at Yerevan’s open-air market known as the Vernissage.

The immediate cause for Russia’s pro-Baku tilt is Ukraine. Azerbaijan, a far bigger and richer country, has not joined in Western sanctions and, unlike Armenia, has displayed no sympathy for Ukraine. But the overarching reason is Putin’s fear of democracy in Russia’s erstwhile empire.

“All of these events are directly related to Russia’s attempt to overthrow Pashinyan and stop his Western pivot,” said Hacopian. He argues it failed. “Everybody blames the Russians. Armenia is now the most pro-American state in the region. Russia’s moves backfired.”

Olesya Vartanyan, senior South Caucasus analyst at the International Crisis Group, concurred. “Nagorno-Karabakh is at the center of Armenian identity, and the Russians allowed it to collapse. They lost Armenian society,” Vartanyan told Al-Monitor.

This marks a sea change. Armenia was among the most pro-Russian of the former Soviet states. According to a contested version of history, imperial Russia opened its doors to tens of thousands of Armenians fleeing the genocide. More than half of Armenia’s current population is thought to be their descendants.

Western observers contend that anti-Russian sentiments are currently so high that Pashinyan is off the hook. However, interviews with multiple Armenians across the country suggest otherwise. “He gave away everything,” said Markar Martirosyan, who runs a pet shop in Yerevan. “Pashinyan is zibil,” Martirosyan added, using the Armenian slang for animal poop or garbage, which is the same in Turkish.

“Turkey’s man”

It hasn’t helped that talks with Turkey have led nowhere. The land border remains shut and diplomatic relations have not been established. None of this stopped Pashinyan from joining Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s inaugural bash in Ankara following his electoral victory in May.

Pro-government Turkish hacks mockingly refer to him as “our man.”

“Pashinyan is very naive,” said political analyst Grigoryan. “He made unilateral concessions without getting anything in return. He is a gift to Aliyev, to Erdogan.” Pashinyan reckoned that detente with Turkey would deter Azerbaijan from further assaults. “It’s hard to speak of a peace dividend when your country is flooded with refugees,” Grigoryan noted.

The notion that Armenia could decouple so easily from Russia is every bit as naive. For starters, 40% of Armenia’s exports go to Russia. Russian state enterprises control 90% of Armenia’s power-generating capacity.

Many in the Armenian diaspora — notably hard-liners in the influential Armenian Revolutionary Federation who advocate friendship with Russia — agree. They label Pashinyan “Turk” and claim he will make Armenia a Turkish vassal.

The setbacks are taking a toll. In mayoral elections held on Sept. 17, Pashinyan’s Civil Contract party saw its popularity slip amid growing apathy with only 28.5% of eligible voters casting their ballots. Yet it still trounced its rivals. This is because the majority of Armenians still regard him as the lesser evil.

Opposition demonstrations that erupted in the days following Azerbaijan’s attack have fizzled out. Putative rival Hakob Baboudjian, who staged an anti-government protest Saturday in Yerevan’s iconic Republic Square, said he would “deploy deep psychology and quantum physics” to unseat Pashinyan. “I will make the nation happy. I will heal the population,” he told Al-Monitor as a small band of followers looked on.

Still, it would be unwise of Pashinyan to lapse into complacency. Feeding and accommodating over 100,000 people — many of them subsistence farmers with few skills — will pose a huge challenge. The initial solidarity felt by Armenians for their ethnic kin may shift to resentment. Many accuse the so-called Karabakh clan, which held power prior to Pashinyan, of holding Armenia hostage to their own narrow interests, rejecting any concessions that might have resulted in peace with Azerbaijan and Turkey. “They created an emergence of a segment of society that associates Nagorno-Karabakh with criminality,” said Hacopian.

Coups and land grabs

More immediately though, what if Azerbaijan decides to attack again? EU-meditated peace talks between Pashinyan and Aliyev are set to resume in the Spanish city of Granada on Thursday. “Should the peace talks collapse, this will increase the risk of further escalation. One day we can wake up to see another military operation and another change of landscape in the region,” said the Crisis Group’s Vartanyan.

Baku wants to connect Azerbaijan to Nakhichevan, an Azerbaijani exclave that borders Turkey. Aliyev insists that Azerbaijan should be granted unfettered access through a proposed land corridor and not be subjected to border controls. Armenia ripostes that not only would this constitute a breach of its sovereignty, but it would effectively cut it off from its southern neighbor and closest regional ally, Iran.

Turkey favors the scheme because this would allow it direct access to Azerbaijan proper and to Russian and Central Asian markets that lie beyond. Russia is also on board provided that its own forces monitor the corridor.

Armenia’s real and not unreasonable worry is that Baku will use the corridor as a launching pad to invade Syunik, the southern region that separates Nakhichevan from Azerbaijan. Israel would be delighted. It uses Azerbaijan soil to spy on Iran. In exchange, Israel provided weapons in the last two Nagorno-Karabakh wars. Iran has declared any such move cause for war.

In an ominous portent, Azerbaijan has occupied an estimated 125 square kilometers of Armenian territory since 2020. Western inertia in the face of the past week’s events may embolden Aliyev to make another land grab, sowing the seeds of yet another cycle of bloodletting. This would be all the more likely should Russia succeed in ousting Pashinyan and install its own apparatchiks, most likely in a coup. The Kremlin could revert to its old tactic of playing one side against the other.

Would the United States or the Europeans intervene? “They did nothing when [Abdel Fattah] al-Sisi seized power in Egypt. Why would they act for a small and less important country like Armenia?” asked Firdevs Robinson, former Caucasus and Central Asia editor for the BBC.

“The man in the street would think ‘hard power decides everything. Human rights is bullshit,’” said analyst Poghosyan. “This view is shared by everyone in Armenia.”

Back in Goris, geopolitics are far from the refugees’ minds. “What hurt me the most was to see the cemetery where all our soldiers are buried,” said Karapetyan, the cleaning lady. “The knowledge that we won’t ever see them again, the knowledge that they died in vain is impossible to bear.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News