Summary:

China is leading the international rulemaking process to regulate deep-sea mining, but Washington can still blunt Beijing’s advances (and protect the environment in the process).

There are still no international rules for the nascent deep-sea mining industry, which is only now gearing up to exploit the untold wealth of the international seabed. This immense area beyond national jurisdiction contains abundant critical minerals—among them huge concentrations of cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, and manganese, which are essential to green and renewable energy technologies and many defense and aerospace applications. But only in the past few years has the practical possibility of industrial scale seabed mining been within reach.

China has been positioning itself to be the central rulemaker in the international deep-seabed area. As a party to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), China has worked for decades to shape the broader law of the sea from within the treaty regime. From its position within the UNCLOS framework, China’s leaders have subsequently placed major bets on the strategic and economic value of the deep seabed. Meanwhile, America is not an UNCLOS member. On the deep seabed, as on so many other vital maritime issues, the United States sits on sidelines of the “rules-based international order” it professes to lead.

The stage is now set for a pitched diplomatic battle over the rules and regulations that will govern activity in this vast, unexplored frontier. “The Area” of seabed beyond national jurisdiction accounts for half of the ocean floor and perhaps substantially greater proportions of the planet’s critical minerals and hydrocarbons. With technologies rapidly maturing, the multilateral negotiations to set rules for commercial exploitation of seabed minerals have reached a “critical phase,” according to Chinese officials. China’s foreign affairs chief, Wang Yi, recently crowed to the UN about China’s success in aligning itself with “the vast number of developing countries committed to changing the old maritime rules of a backward era.”

Whatever those rules will ultimately be, the United States is not currently in the picture. Instead, China contends with the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and scattered voices from across the developing world, scientific community, and environmental organizations. This group’s appeals to scientific knowledge and precaution against marine environmental harm form a fragile counterbalance against China and the rush to extract deep seabed minerals. As U.S. leaders begin to focus on building the resilience of critical mineral supply chains, there should be corresponding urgency to bring a strong and focused U.S. voice to the negotiations. In the context of long-term strategic competition with Beijing, Washington’s self-imposed exclusion from this rulemaking process is an egregious oversight.

China’s Dominant Position on the Seabed

China is the only heavyweight in multilateral negotiations to set new rules for extraction of deep-seabed minerals. Beijing’s strength is especially clear at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the UNCLOS body based in Kingston, Jamaica, charged with regulating the establishment and conduct of deep-seabed mining activities.

At its annual meetings in 2023, the ISA failed to agree on licensing and technical rules for exploitation of seabed minerals, missing the two-year window triggered by a bold application by Nauru and a Canada-based mining conglomerate, the Metals Company. Chinese delegates nonetheless managed to single-handedly prevent the ISA from initiating proceedings to consider a precautionary pause on mining licenses, as advocated by many developing countries and some key voices from Europe. This controversy will return to the fore when the ISA assembles in Kingston in July 2024, where China will mount yet another campaign to remove obstacles and quickly promulgate new deep-sea mining rules.

Chinese officials and technical experts have already been taking proactive steps to address “the problem of the shortage of rules” for deep-sea activities, seeking to bring them quickly into existence on terms that advantage Beijing. Chinese officials’ comments on draft regulations for exploitation of the deep seabed have tended to neglect environmental and technical concerns and support the full utilization of the international seabed area “as soon as possible.” A permissive, first-come, first-served regime along the lines of what Beijing advocates would allow Chinese state and commercial entities to rapidly deploy huge scale advantages in marine science and technology, mining capacity, and autonomous vehicles and sensors with direct military applications. China’s relative “dominance in critical minerals and mineral supply chains” on land gives it another big leg up as these sea-based resources come online.

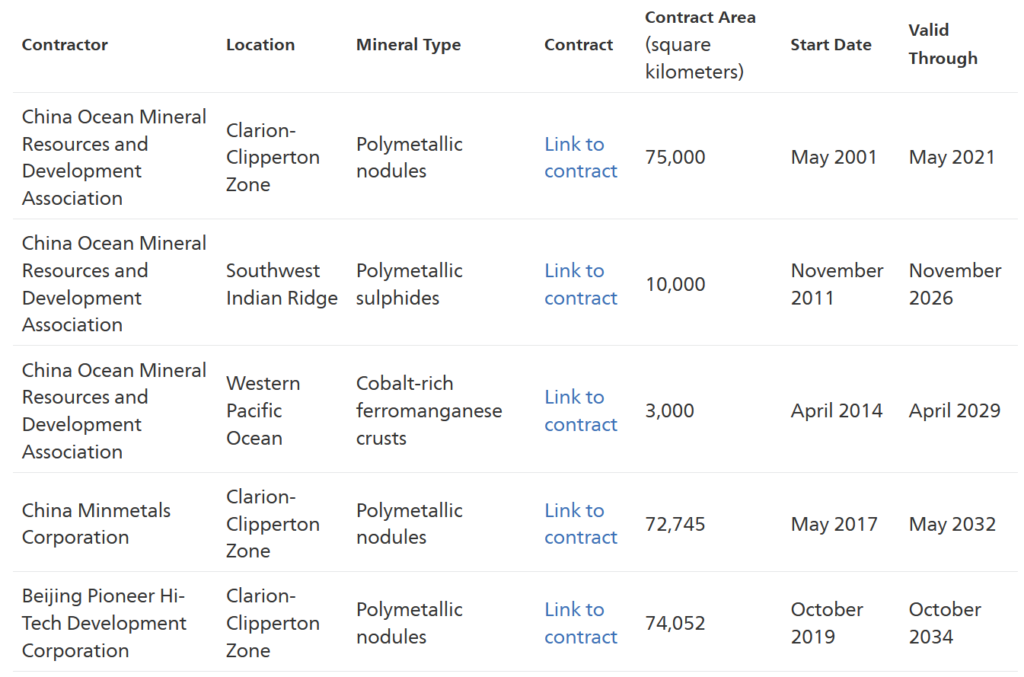

As the state with the most active contracts to explore each of the three types of seabed mineral deposits—it has five of only thirty-one contracts issued thus far (see figure 2)—China is uniquely positioned to shape the market for seabed minerals and the rules governing their exploitation.

To that end, the Chinese delegation is large and active in the ISA. China is the ISA’s main funder; Chinese bureaucrats staff and lead ISA bodies at high rates and provide training for ISA technical experts from the developing world at its advanced “national deep sea base” facilities in Qingdao.

So far, only a sketch of China’s vision for maritime order is observable. Its grandiose but substance-free proposals to build a “maritime community of shared destiny” (海洋命运共同体) do not convey much beyond aversion to U.S. hegemony and reverence for “Chinese wisdom.” Whatever that entails, it does not evidently require much caution about resource conservation or environmental protection, nor accord much respect to the strong views of small states.

China’s Strategic Interest in Making Deep-Sea Rules

China’s long-standing interest in seabed mining is accelerating under President Xi Jinping, who has championed programs to increase the country’s “maritime power” (海洋强国). Xi has personally stressed the strategic and economic stakes in the deep seabed: “To get at these deep-sea mineral treasures, it is necessary to master key technologies in deep-sea access, deep-sea exploration, and deep-sea development.” The sprawling maritime bureaucracy, industry, naval, and scientific apparatus below him has sprinted to secure those objectives. Four basic motivations underly this push into deep-sea activities and technologies.

Security priority. In line with Xi’s vision of “holistic national security,” the deep seabed was prominently included in China’s 2015 National Security Law. The legislation groups it with other “strategic frontier” issues by tasking the state to “preserve the security of our nation’s activities and assets in outer space, seabed areas and polar regions.” Xi’s “security obsession” has brought national security concerns to the foreground of many economic fields formerly managed by technocrats. A new class of securocrats is empowered to centralize party control across state and private institutions (see table 1). China’s mineral industry has been subsumed into Xi’s program to concentrate power within his security apparatus. The industry’s many exquisite technologies for deep-sea exploration and extraction are among those that the People’s Liberation Army is seeking to “fuse” with military technologies and applications.

Table 1. China’s ISA Contracts for Deep-Seabed Exploration

Economic interest. Overall, China’s economy is starved of natural resources. Chinese leaders have undertaken bold measures to shore up its control over critical mineral and energy supply chains. Raw material–intensive manufacturing and heavy industry remain pillars of China’s economic model. Industrial policies to promote advanced manufacturing, in particular, only deepen China’s dependence on such inputs. China relies on huge and growing volumes of imported critical minerals from unstable countries; acquiring huge volumes of seabed resources and transporting them directly to China would buy down some of that risk and expand China’s already dominant role in critical mineral supply chains and production.

Strategic military advantages. Research on and deployment of technologies supporting deep-sea mining provide intrinsic value for a range of military objectives. The technical and scientific capacity required to operate at extreme temperatures and pressures are directly relevant for military hardware and training. Scientific data on depth, temperature, salinity, currents, and marine topography collected in the course of surveying contract blocks can also provide critical information advantages in undersea and anti-submarine warfare. Key deep-sea mining technologies are readily repurposed for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions, as well as potentially for kinetic strikes. China’s “Three Dragons” program includes manned submersibles, autonomous underwater vehicles, and remotely operated vehicles—a trifecta that operates in support of China’s deep-sea mining efforts in some strategic geographies, including blocks near U.S. military installations in Hawaii and Guam. “Once we control the deep sea,” writes a PLA analyst, “we can not only effectively ensure our own surface and underwater security, but also deploy offensive weapons to attack important targets such as the opponent’s large ship formations and naval bases.”

Diplomatic opportunity. The international seabed is an ideal venue for China to flex its rulemaking power and address some perceived strategic vulnerabilities. On the rulemaking front, Chinese experts often stress that global governance is quite thin in these remote areas beyond national jurisdictions, where there is limited treaty law beyond the bare-bones architecture provisionally established under the ISA. Crucially, even customary international law for exploitation does not exist because deep-sea mining has never been done at commercial scale. China will directly influence this new set of customary norms and standards by dint of the sheer scale and persistence of its efforts to put its preferred rules in practice.

Can Washington Compete?

Without a formal voice at the ISA, the United States is relegated to observer status. American diplomats may furiously scribble comments opposing China’s favored principles into the margins of drafts, but they still cannot vote. However, China’s activism at the ISA also creates some diplomatic opportunities for the United States. By pressing ahead despite environmental opposition and without solidarity with the developing world, Beijing has made itself vulnerable. Even if the United States cannot ratify UNCLOS (and thus become eligible for the ISA), there are at least three ways Washington can reposition to blunt Beijing’s advances in this domain—and perhaps even protect the marine environment in the process.

Join the environmental caucus. China has put itself on the wrong side of the green revolution on this issue and could be isolated diplomatically on that account. By championing a reckless lurch into full-scale commercial mining, China undoes its work elsewhere to brand itself as a responsible environmental stakeholder. Chinese mining entities have tried to greenwash their operations, but the reality of inevitable harm to fragile ecosystems is inescapable. Because it is not a member of the ISA, the United States cannot directly contract to mine the Area, so it may as well slow down the process and join the international movement for environmental precaution.

Exploit China’s contradictions. China’s position on maritime rules has changed dramatically since the 1970s, when it championed developing countries’ interests against rapacious maritime powers. Now, China is itself the rapacious maritime power, throwing its weight behind an extractive industry to enrich itself at the expense of weaker states that had expected collective benefit from the new regime. This puts Beijing far out of step with the core norm that resources in the international seabed are the “common heritage of mankind,” not the property of the most technically advanced and aggressive nations. China pays lip service to the “common heritage” norm when it tries to align itself with “the developing countries committed to changing the outdated rules” as Wang Yi put it. But it should not go without remarking that China’s ideas for reforming those maritime rules to be more permissive of seabed mining will benefit Beijing at the expense of its favored developing world constituency.

Ratify treaties to lead the rules-based system. The United States is destined to remain on the periphery of this critical new regime if it persists in operating under its own exceptional rules. Lockheed Martin holds contracts for deep-seabed exploration under U.S. law, yet it is likely that “any rights a U.S. company may have domestically are not secured internationally because U.S. companies are not able to go through the internationally recognized process at the ISA.” The U.S. decision to act as though the ISA does not exist is also inconsistent with U.S. rule of law values. Furthermore, it makes China look like it is the more cooperative major maritime power and the one to whom states should look to for leadership on this critical issue. Ratifying UNCLOS, as well as the new High Seas Treaty, would quickly and directly augment U.S. power and standing under international law at a manageable cost.

The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden should lean in when the ISA convenes in July 2024. China will again be in the uncomfortable position of opposing the interests of developing nations, and for now, the United States will again be in the unimportant position of observer. China’s heavy presence at the ISA and in contract blocks around the world’s ocean have positioned it to shape the new deep-seabed regime in line with its interests. Given the Biden administration’s focus on “shaping the terms of competition,” far greater attention is due along this critical frontier.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News