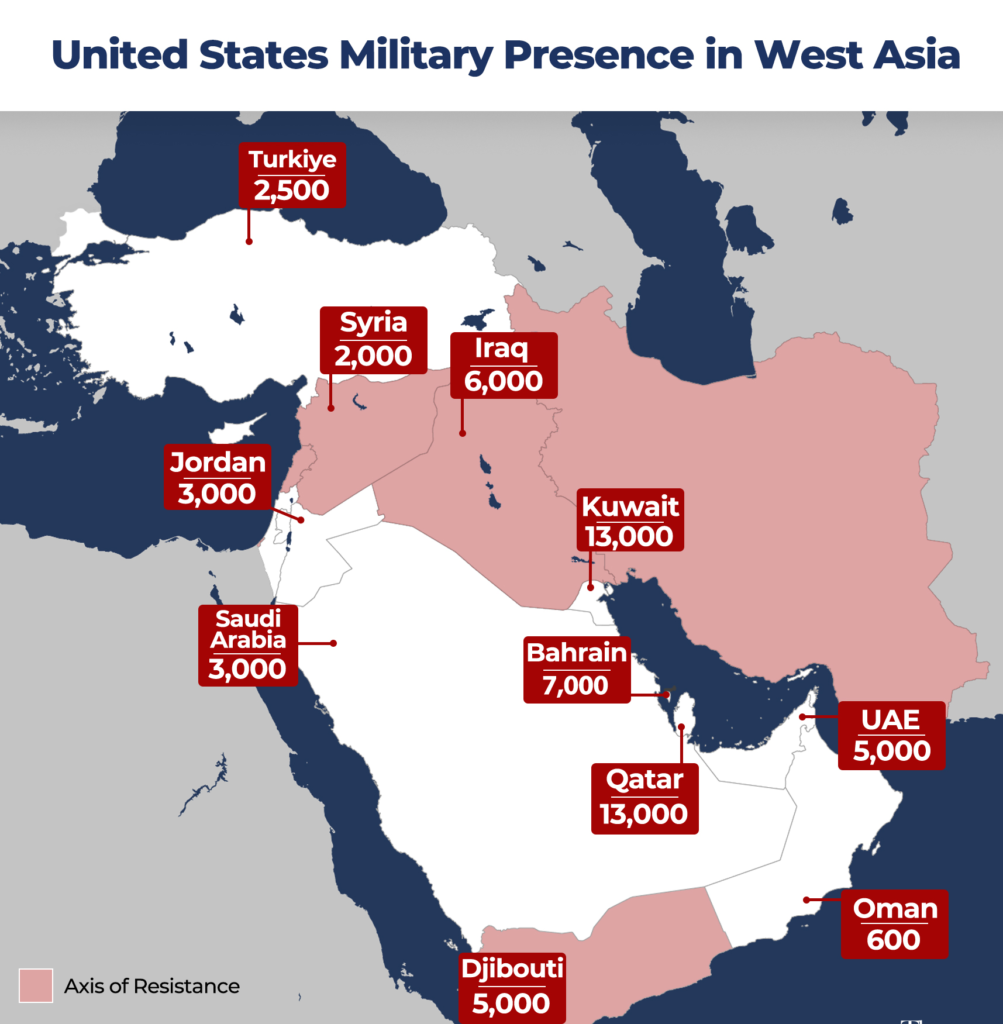

US weapons are dropping on Gaza, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, so some major Arab states hosting US military bases are now telling Washington ‘You can’t launch from here.’

In West Asia, the bedrock of US power projection lies in its strategically located military bases nestled within the Persian Gulf. However, the future of these vital installations appears increasingly uncertain as geopolitical alliances shift toward multipolarity, hastened by the multi-front war unfolding in the region.

The fallout from Israel’s brutal military assault on Gaza and unconditional US support for it are accelerating these shifts. Traditional allies like Saudi Arabia and the UAE – once steadfast in their partnership with Washington – are now charting more independent courses, cautiously avoiding entanglements that could lead to broader conflicts, particularly with Iran and its Axis of Resistance allies.

Indeed, this recalibration, coupled with the Persian Gulf states’ concerted efforts toward economic diversification beyond oil, is gradually eroding the sturdy foundations of long-standing partnerships.

The question now is how these shifts will affect US military presence in the region and the ability of Americans to operate from their established bases.

US strategic outreach

At the heart of the US military’s Persian Gulf position lies a network of strategic Defense Cooperation Agreements (DCAs) inked with each host country. These agreements delineate the terms of military collaboration, categorizing states into two distinct groups: those designated as major non-NATO allies (MNNA) and those that are not.

This classification informs the depth and scope of military cooperation, including strategic benefits and obligations. As per the US State Department, 18 countries globally are recognized as MNNAs: Argentina, Australia, Bahrain, Brazil, Colombia, Egypt, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines, Qatar, South Korea, Thailand, and Tunisia.

Achieving MNNA status under US law represents a significant acknowledgment of a country’s strategic partnership with Washington, offering a spectrum of benefits in defense trade and security cooperation.

This prestigious designation is not merely a token of enhanced military and economic interactions; it symbolizes the profound respect and recognition of the deep-seated relationships the US holds with these countries. But despite the privileges afforded by the MNNA status, it’s crucial to note that this classification does not imply any automatic security commitments from Washington.

These privileges include eligibility for loans of materials for research and development purposes, placement of US-owned War Reserve Stockpiles on the ally’s territory, and the potential for reciprocal training agreements.

Moreover, MNNA countries are prioritized for receiving Excess Defense Articles and may be considered for purchasing depleted uranium ammunition. These states can engage in cooperative defense research and development projects with the US, allowing their firms to compete for Department of Defense contracts for maintenance and overhaul services outside the United States.

This also encompasses support for acquiring explosives detection devices and participating in counter-terrorism initiatives under the Department of State’s Technical Support Working Group.

Pushback in the Persian Gulf

Among the Persian Gulf states, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar have been distinguished with MNNA status, while Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Oman are not. The US military’s strategic presence in the region aligns with these categorizations.

The 7 October Hamas-led attacks, Al-Aqsa Flood, and subsequent developments in West Asia have prompted Saudi Arabia and the UAE to adopt positions distinct from other Persian Gulf states concerning support for US military operations in the region.

The possibility that the US may shift some of its military forces to the Asia–Pacific region to counter the rising global power of China has compelled Saudi Arabia and the UAE – countries heavily reliant on the US for their security – to explore alternative security arrangements.

The transition from a unipolar to a multipolar global system, alongside increased interest from Russia and China in the Persian Gulf, aligns with these powers’ quest for new security solutions, significantly altering the region’s political and economic dynamics.

Most importantly, however, and in the context of the Gaza war and its regional repercussions, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi appear most concerned about the possibility of US military operations in West Asia escalating into a large-scale military conflict involving Iran.

The prime illustration of this concrete example is Saudi Arabia’s and the UAE’s de facto non-participation in Operation Prosperity Guardian (OPG), the US-led naval coalition formed in December 2023 to respond to Yemeni attacks on Israeli-linked shipping in the Red Sea – and Riyadh and Abu Dhabi’s refusal to allow the use of US bases in their territories for Operation Poseidon Archer, a joint US–UK military effort targeting Yemeni territories under the administration of the Ansarallah-aligned government.

‘Not from our bases’

Politico reports that the UAE has imposed restrictions on the Pentagon’s ability to conduct retaliatory airstrikes against Iran’s regional allies. The US refrains from using fighter jets from these bases for attack missions to avoid escalating tensions between Arab states of the Persian Gulf and Iran.

Over 2,700 US military personnel and 3,500 US forces are deployed at Prince Sultan Air Base in Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s Al Dhafra Air Base, respectively. The latter also serves as the Gulf Air Warfare Center and accommodates a significant contingent of US aircraft that participate in regional operations. This includes a variety of fighter jets and reconnaissance drones, notably the MQ-9 Reapers.

In recent weeks, US President Joe Biden has authorized several air and missile strikes, targeting Iran-supported resistance entities across West Asia. Factions close to Iran have launched 170 attacks on US forces stationed in mainly Iraq and Syria since last October, employing drones, rockets, and missiles in an effort to oust US military presence from the region.

To date, these attacks have resulted in the deaths of three US service members and injured numerous others. Concurrently, Yemen’s Ansarallah-supported military has allegedly conducted 51 operations on maritime vessels navigating the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, marking an uptick in attacks since the operation commenced on 19 November.

Unsustainable strategies

However, this US military approach is not sustainable for Washington in the long term. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are seeking to resolve their issues with Yemen after an eight-year war that heavily depleted their finances and drew missile fire into their major cities and against energy infrastructure targets.

The Saudi Foreign Minister stated in an interview with France 24 on 19 February that “a peace deal between the government of Yemen and the Houthis was close, and that Riyadh would support it.”

Under these conditions, the US is unlikely to engage in actions that could reignite tensions between Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Sanaa. Nevertheless, maintaining a constant aircraft carrier group off the coast of Yemen for Operation Poseidon Archer and airstrikes against Iranian interests will be a costly and challenging endeavor for the Americans.

While bases in Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar, which have MNNA status, remain crucial for the US, Washington’s unilateral veto of UN Security Council resolutions for a Gaza ceasefire – and its unconditional military and political support for Israel, despite the tens of thousands of deaths of women and children in Gaza – have inflamed anti-US sentiment on the Arab street, which today overwhelmingly rejects normalization deals with Tel Aviv.

For now, China is quietly observing the erosion of US stature in West Asia, potentially waiting for an opportune moment to – with support from Moscow – launch a diplomatic initiative to resolve the Israel–Palestine issue, away from American interference.

It wouldn’t be the first time the new multipolar powers stole Washington’s spotlight in the Persian Gulf: the Beijing-brokered Iran–Saudi rapprochement in March 2023 not only took the US by complete surprise but demonstrated to regional states that dealmaking was possible without the US.

The shifts underway in the Persian Gulf will, for certain, have an impact on US military and diplomatic strategy. But deactivating US bases during an active regional conflict involving American forces is something new altogether.

When the dust settles, what will be the point of these multi-billion dollar military installations when US fighter jets or missiles cannot be launched from them?

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News