Key points

- The war between Israel and Hamas has increased the threat to U.S. troops in the Middle East, particularly for the 3,400 personnel in Syria and Iraq. Since October 7, 2023, dozens of U.S. troops have been injured in attacks perpetrated by Iran-backed Shia militias in both countries, at times resulting in U.S. retaliatory strikes.

- Defensive measures and luck have prevented U.S. fatalities thus far. But U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq are at significant risk as long as they remain deployed there.

- If a U.S. ground presence served a core security interest, that risk might be reasonable. But there is no good reason to risk U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq, where ISIS’s capabilities have been degraded, capable local actors eagerly hunt the group’s remnants, and the United States can still strike from long distance, if necessary, without local bases.

- Instead of enhancing U.S. security, the U.S. force presence in Syria and Iraq pointlessly risks war with Iran. Sending additional troops to the Middle East compounds the problem and grants U.S. adversaries in the region added leverage by giving them the ability to threaten U.S. forces.

- The added danger to U.S. forces is one more reason to withdraw from Syria and Iraq as a step toward de-prioritizing the Middle East more generally.

The Israel-Hamas war increases the danger to U.S. troops

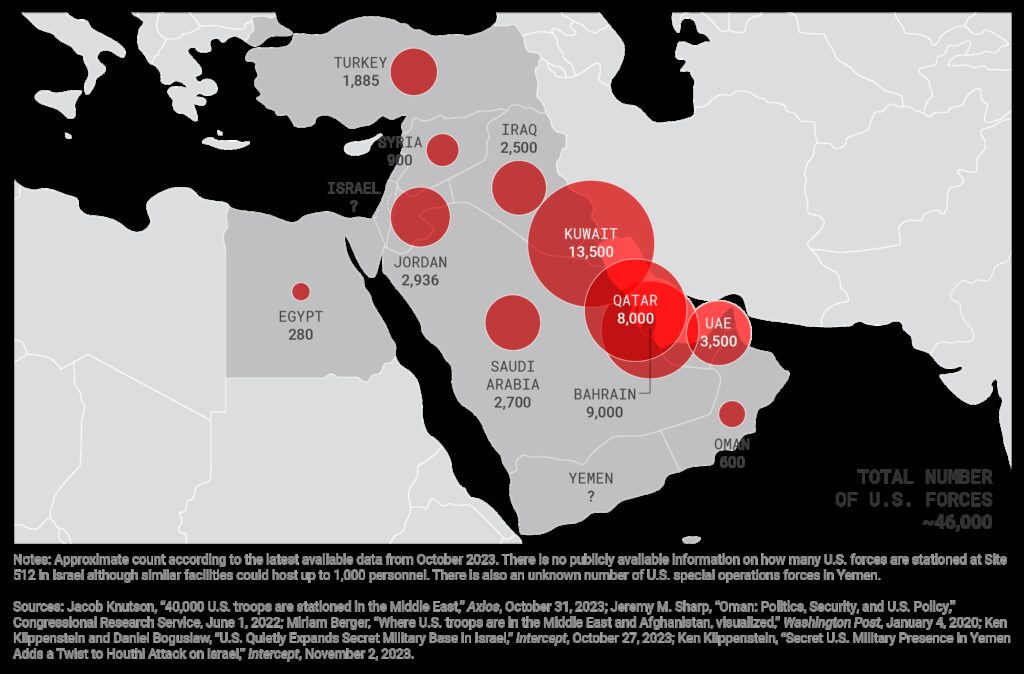

With 46,000 troops spread across a network of bases throughout the Middle East, the United States has far more force there than necessary to serve its key interests of defending against anti-U.S. terrorist threats, preventing disruptions to the flow of oil, and ensuring no regional power can achieve hegemonic status.1 The United States can meet these narrow interests without the high cost and baggage of a bloated force posture.2 The U.S. counterterrorism apparatus, consisting of intelligence assets, high-technology surveillance, and strike capabilities, allows the United States to strike terrorists wherever they operate in the region.3 The prospects of any Middle Eastern state attaining hegemony are slim to none; Iran’s conventional military capabilities are unimpressive, and the region’s major powers are frequently divided against themselves.4 While oil shocks are a concern, previous price hikes have been quickly settled after a short period of disruption.5

The U.S. troops in Syria and Iraq are in an especially dangerous situation compared to bases in the Persian Gulf. Approximately 3,400 U.S. troops (roughly 2,500 in Iraq and 900 in Syria) remain deployed in pursuit of a mission—the enduring defeat of ISIS—that is defined in such maximalist terms as to demand a perpetual U.S. deployment in both countries.6 Once viewed as critical assets to accomplish counterterrorism goals, U.S. bases in Syria and Iraq have turned into liabilities and enable U.S. adversaries, including Iran and Russia, the opportunity to dial up the pressure.

The risk to U.S. military personnel has grown since October 7, when Hamas perpetrated the deadliest terrorist assault on Israel since its establishment in 1948. Since the Hamas attack, the Biden administration has sent more forces into the region in what U.S. officials justify as an attempt to deter escalation and prevent the war in Gaza from spreading to other fronts in the region. On October 14, the U.S. Department of Defense deployed a second carrier strike group, the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower, to the Eastern Mediterranean.7 An additional F-16 squadron and air defense systems accompanied the carrier strike group.8 At the time of writing, approximately 17,000 additional U.S. troops have been deployed to the Middle East, both as a force protection measure and to deter Iran and Hezbollah from getting more involved in the fighting.9 The Biden administration has also sent messages to both actors stressing that the United States has no intention of expanding the war while warning Iran and Hezbollah from doing the same.10

The United States still maintains a robust military presence in the Middle East with approximately 46,000 forces stationed across the region.

Enlarging the U.S. force presence could restrain Iran from entering the war directly, although Iran has expressed little desire to intervene. But it also entails significant risk for the United States of being drawn into a needless war, potentially with Iran. Some escalation has already occurred. Hezbollah, which is backed by Iran, has fired rockets and drones at Israel since the attack, drawing Israeli counterfire.11 Casualties occurred on both sides. The Houthis, which control most of Yemen’s population centers, launched several drones and ballistic missiles in Israel’s direction, shot down a U.S. drone off Yemen’s coast, and have periodically fired missiles near the vicinity of U.S. warships in the Red Sea.12 The United States has shot down some of these drones as a force protection measure and is discussing possible military options against Houthi targets in Yemen.13

Most important from a U.S. perspective, from October 17 to December 15, Iran-backed militia groups have attacked U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq more than 100 times, injuring more than 60 servicemembers.14 On October 26, November 8, and November 13, the Biden administration responded to these attacks by conducting airstrikes against militia sites in eastern Syria also used by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).15 On November 21, November 22, and December 3, the United States expanded its target set to include militia facilities in Iraq, angering the Iraqi government in the process.16

Attacks against U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq between October 17 and December 15, 2023

Since the start of the Israel-Hamas war, attacks on U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq have spiked. Such attacks by Iranian proxies endanger U.S. forces and could spark a larger conflict.

Despite U.S. retaliation, drone and rocket attacks on U.S. bases in Syria and Iraq have continued and will be a persistent, lethal threat as long as U.S. troops are stationed there. The best way to mitigate risk and prevent escalation that could lead to regional war is for the Biden administration to order a withdrawal from Syria and Iraq. As this paper argues, all of the conventional arguments used to rationalize a continued U.S. presence in both countries—a possible resurgence of ISIS, concerns about U.S. credibility after a withdrawal, and an emboldened Iran taking advantage of a U.S. departure—are overstated and wrong.

Why withdrawal is the right choice

ISIS is no longer a coherent organization that threatens the United States. ISIS’s military capabilities have been significantly degraded by U.S. and coalition counterterrorism pressure and its scattered remnants do not justify perpetual U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq. ISIS fighters, relegated to a low-grade insurgency in Syria and Iraq, no longer control or govern territory in either country. Yet U.S. troops continue to prosecute a counter-ISIS mission whose objective is so maximalist as to be unattainable. Meanwhile, non-ISIS threats such as Shia militias target U.S. positions, at times resulting in U.S. military retaliation that has failed to deter the attacks. The costs of an indefinite U.S. troop deployment in Syria and Iraq simply outweigh the benefits.

The U.S. accomplished its counter-ISIS mission

In September 2014, the Obama administration began striking ISIS targets in Syria.17 The goal at the outset of the military campaign was achievable: roll back the territorial gains ISIS accrued in the years prior to the U.S. intervention and eliminate its so-called territorial caliphate. At the time of the first U.S. airstrikes, ISIS was a formidable organization, with the Central Intelligence Agency estimating as many as 31,000 fighters in its ranks.18 The group, having ousted the Iraqi military in the north and west, once controlled territory from Raqqa in north-central Syria to the suburbs of Baghdad.19 ISIS served as the de-facto governing authority in this wide area, and its control of approximately eight million people provided it with the ability to raise significant funds through taxation and fees.20 In 2014, at its height, ISIS also made an estimated $1 million a day by selling oil on the black market.21

The U.S. air campaign in Syria and Iraq, coupled with corresponding ground operations by U.S. special operations forces, the Iraqi army, the pro-Iraqi government Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), eliminated the ISIS caliphate. In September 2014, ISIS lost control of Baquba, Iraq. In March 2015, ISIS forces were pushed out of Tikrit, a major Iraqi city in the north. Ten months later, the Iraqi security force captured Ramadi, and the organization would be pushed back from Fallujah, Abu Ghraib, and Manbij in 2016.22 In December 2017, five months after Mosul was liberated, the Iraqi government officially declared the end of the ISIS caliphate in Iraq.23 By March 2019, the last patch of ISIS-controlled territory in Syria was eliminated.

Instead of declaring success and withdrawing, the United States enlarged the mission by embracing goals that would require a long-term U.S. troop investment—if they could be realized at all. In Iraq, U.S. troops are now tasked with training, advising, and equipping the Iraqi security forces to the point where it becomes an independent, professional fighting force capable of defending Iraq from all threats foreign and domestic. However, U.S. officials have never explicitly defined what “professional” means in this context or explained what benchmarks are being used to determine whether Iraq has met the threshold. Joint statements between U.S. and Iraqi defense officials, most of which stress generalities about ongoing U.S. efforts “to develop Iraq’s security and defense capabilities,” tell us little.24

Across the border in Syria, U.S. policy is even more complicated. In contrast to Iraq, the Biden administration has multiple objectives: deterring a Turkish military offensive against Kurdish-administered territory in the east, keeping the peace between the Kurdish-led SDF and Arab tribes in Deir ez-Zor, preventing the Syrian government from re-capturing Syria’s northeast, and the enduring defeat of ISIS.25 The first three goals on the list are not core to the limited U.S. security interests in Syria or the broader region, while the last goal—the “enduring defeat” of ISIS—implies destroying the organization in its entirely and resolving the political and socioeconomic conditions that make its reemergence impossible. Such a task in a best-case scenario would involve reordering Syrian society and governance over decades, which is ill-defined and infeasible.26

ISIS is a shell of its former self

Since 2019, ISIS has degenerated from a proto-state to a rural insurgency limited to unsophisticated attacks against local targets like Iraqi army checkpoints and SDF patrols. Iraq’s counterterrorism forces are increasingly capable of mounting independent operations against ISIS targets in the north and west, where the bulk of the group’s activity is located.27 Although ISIS has exploited the lack of security coordination between the Iraqi government and the semi-autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in disputed territories like Kirkuk province, a U.S. troop presence in Iraq does nothing to resolve this long-running governance problem. ISIS’s senior and mid-level ranks are under constant military pressure, compelling the group to operate as more or less independent bands and undermining its ability execute attacks. Four ISIS “caliphs,” or rulers, have been killed since 2019.28 The last ISIS caliph, Abu Hussein al-Qurashi, was killed five months after being appointed to the position.29 Breaking ISIS detainees out of Iraq’s prison system and the SDF’s makeshift detention facilities is now one of its top priorities, a reflection of desperation as it seeks to sustain its numbers.30 In Iraq, ISIS’s ability to execute operations in urban areas is significantly curtailed, a product of the Iraqi security forces’ improved competence relative to its previous iteration in 2014, when it largely fled ISIS offensives without a fight. Iraq’s Sunni community is also more willing to collaborate with the Iraqi government than it was in the past. Iraqi Sunnis no longer see ISIS as a better alternative to a predatory Shia-dominated Iraqi army.31

ISIS territorial control (2015–2023)

With the ISIS territorial caliphate destroyed four years ago, the United States could withdraw its forces without undermining its security.

ISIS’s prospects are not any more promising in Syria. Most ISIS activity is confined to the Badia desert, an inhospitable area with a small population, which limits ISIS’s capacity to extort financial resources.32 Previous ISIS attacks in the Badia desert have instigated strong retaliation from the Syrian military, including ground campaigns with Russian air power in support.33 The SDF, the Syrian government, Iranian-linked militias, Russia, and Turkey have all conducted counter-ISIS operations in select parts of the country. Because preventing the regeneration of ISIS is a core security interest for all of these actors, these operations will continue after U.S. troops depart.34

U.S. military presence is poor policy

Some claim that an indefinite U.S. troop presence in Syria and Iraq is a low-cost endeavor, or at the very least a lower cost option than withdrawal.35 Others state that withdrawal would create a vacuum that Iran, Russia, and Syria would fill and thereby become more threatening.36 Still others promote the notion that withdrawal from Syria would betray Washington’s Kurdish partners, harm U.S. credibility, and embolden U.S. adversaries in other regions of the world to take actions that challenge or undermine U.S. interests.37 All of these arguments are wrong.

First, a continuous U.S. troop presence is not low-cost to the men and women responsible for carrying it out. U.S. troops have been attacked by a multitude of actors hundreds of times since the 2019 elimination of ISIS’s territorial caliphate, some of which caused fatalities. According to the Defense Intelligence Agency, Iraqi Shia militias attacked U.S. positions in Iraq more than 300 times between late 2019 and April 2021.38 Before the Israel-Hamas war, 83 such attacks occurred during the Biden administration.39 Dozens more have transpired since then.40 If U.S. ground troops were essential to keeping ISIS contained, then a case could be made that the risks posed by militia strikes were the cost of doing business. But as stated above, other actors are highly likely to continue pressuring ISIS militarily for their own reasons regardless of U.S. policy—and such pressure may even increase once U.S. forces are gone.

Second, U.S. bases in Syria and Iraq may not cost much now, but they create great risk. The bases are strategic liabilities, providing Iran and the militias it sponsors with an easy way to target the United States to register disapproval of U.S. policy. When the Trump administration assassinated IRGC-Quds Force Gen. Qassem Soleimani, Iran retaliated by launching a dozen ballistic missiles at two U.S. facilities in Iraq.41 Fortunately, no Americans were killed in this specific attack. Even so, the United States nearly attacked Iran in retaliation.42 If U.S. fatalities had occurred, the United States probably would have retaliated harshly against Iranian assets in Syria and perhaps even in Iran itself. The odds of a limited clash spiraling into a regional war would then increase markedly, putting the U.S. military’s entire base network in the Middle East at risk. The same dynamic holds true today and will continue to hold true for as long as U.S. ground troops are present in bases across Syria and Iraq.

Third, according to the so-called “vacuum theory,” a U.S. withdrawal would not only degrade U.S. power and influence in the Middle East but also encourage its adversaries. Yet the relatively stable balance of power among states in the region will likely hold after a U.S. troop departure in Syria and Iraq.43 Even if Iran did succeed in exploiting a U.S. withdrawal for its own purposes, regional powers like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates would not be passive spectators. In Iraq, for instance, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have sought to improve relations with Baghdad to maximize their own geopolitical flexibility and balance Tehran’s influence in the country.44 Syria, which will remain poor, unstable, and politically fractious for the foreseeable future, is more likely to be a burden for those who fill the so-called vacuum than a benefit.45

Fourth, with respect to credibility, what the United States chooses to do in Iraq or Syria tells us little about how the United States would act when direct or higher priority U.S. security interests were at stake. Despite the conventional wisdom, foreign leaders don’t rely on a state’s past behavior to predict how that same state will behave in the future.46 Hard power and national interests, not past actions, are far more important factors in assessing a state’s willingness to act in a given contingency.47 Just as the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam didn’t break the U.S. alliance system in Europe or Asia, a U.S. withdrawal from Syria and Iraq won’t push U.S. allies into the arms of Russia or China, who are unable and unwilling to become the region’s external security guarantor anyway.

Fifth, while Iran and Iranian-backed militias would welcome a U.S. withdrawal from Syria and Iraq, the United States also benefits by not having to fight militias that would otherwise have no interest in targeting Americans. Unlike Al-Qaeda, which has a transnational agenda, the top priority of Syria and Iraq-based militias is compelling a U.S. troop departure. At times, this mission has been shared by the Iraqi parliament.48 Without those bases, the attacks would not be occurring and the militias would no longer be a security concern for the United States.

U.S. deterrence against Iranian-backed militias will continue to fail

The Biden administration has struck Shia militia targets in Syria six times in response to militia and drone attacks against U.S. bases in both Syria and Iraq. In each case, the United States explained these operations as a way to restore deterrence against Iranian-backed militias to prevent similar attacks in the future.49 “The whole point of deterrence theory is not just to put stuff out there, but to demonstrate a credible preparedness to use military force,” a U.S. defense official said after the U.S. strikes on October 26, 2023. “What you saw us demonstrate is readiness to take military action to defend our forces, and we’re ready to do it again — sort of core deterrence theory.”50

But the United States isn’t deterring anything. Despite multiple rounds of retaliatory strikes since October 26, militias continue to conduct drone and rocket strikes on U.S. positions throughout Syria and Iraq.51 At times, militias have retaliated on the same day the United States conducted airstrikes.52

Some analysts suggest the United States can bolster deterrence by increasing the set of militia targets it holds at risk of retaliation, striking more often, and using greater force during its operations.53 Yet these recommendations miss the underlying problem: at its core, deterring non-state actors is extremely difficult. Unlike states primarily concerned with maintaining control over their territory and defending their constituents, non-state groups are largely unencumbered by such concerns and therefore have less restraints on their ability to act.54 Like states, non-state actors go through similar cost-benefit calculations.55 But in places like Syria and Iraq, where militias aren’t necessarily loyal to the state, compete for prominence, and are committed to expelling U.S. forces, attacking the main antagonist—the United States—and enduring the risk of retaliation may be a price worth paying.

Outside of precision airstrikes, the United States has also tried to pressure the Iraqi government into curbing the militia groups. In September 2020, the Trump administration threatened to close the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad unless the Iraqi government stopped the militia rocket attacks.56 On November 5, 2023, Secretary of State Antony Blinken met with Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani in Baghdad to re-emphasize the need for Iraq to crack down on the groups’ activities.57 Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin reiterated this message to Prime Minister Sudani a month later, stressing that “attacks against U.S. forces must stop.“58 But those threats and pleas fell on deaf ears, both because the Iraqi state is incapable of demobilizing the militias and because Iraqi prime ministers rely on them to sustain counterterrorism operations against ISIS. Moreover, these militias have built up formidable military and economic resources on their own accord, which enables them to make their own calculations independent of the Iraqi state.

Taking such considerations into account, U.S. deterrent efforts in Syria and Iraq will continue to fail in the future as they so consistently have in the past. Similar attacks on U.S. bases will be a way of life as long as U.S. forces are operating in Syria and Iraq. For the United States, the most effective and efficient defensive measure is not stronger acts of retaliation but rather withdrawing its troops.

Don’t pick an unnecessary fight with Iran

Preventing war with Iran should be a top U.S. priority, particularly today, when tens of thousands of U.S. troops are stationed in the Middle East.59 While Iran’s conventional military has limited force projection capacity relative to the United States, a war with Iran would nevertheless be a highly costly enterprise. Iran boasts the largest missile inventory in the Middle East and has spent decades building a network of non-state proxies in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Lebanon, Gaza, and the West Bank, which could be utilized in the event of hostilities with the United States. Some of those proxies, like the Houthis, possess missiles with ranges that can reach U.S. bases in the Persian Gulf.60 Iran may conclude that even limited U.S. military action is confirmation that acquiring a nuclear weapon for deterrence purposes is the best option—a decision the Iranian government has not yet made.61 U.S. military action would be a gift to Iran’s hardliners, who would opportunistically exploit a war imposed by outsiders to tout their nationalistic credentials to the Iranian people. Similar to the wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, a bombing campaign against Iran would also be unpredictable and likely last longer than the United States expects.62

Even so, some lawmakers and analysts believe the United States has been overly deferential toward Iran. Hamas’s October 7 attack against Israel has accelerated calls for a tougher U.S. policy on Iran. Sen. Lindsey Graham has advocated for U.S. military action against Iran’s oil infrastructure to undermine its ability to finance groups such as Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iraqi Shia militias.63 Foreign affairs scholar Hal Brands says the United States “must make clear, through the available channels, that attacks on U.S. forces will be met with disproportionate responses against the Iranian military itself.”64 The Biden administration seems to sympathize with the sentiment, to a point. “The United States has taken — and as necessary, will continue to take — military action against the IRGC and its affiliates,” Deputy Assistant Defense Secretary for the Middle East Dana Stroul told the House Foreign Affairs Committee on November 8. “This includes the use of force against IRGC and IRGC-affiliated personnel and facilities in the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility.”65

Yet these recommendations, among other flaws, overstate Iran’s control over proxy groups and would lead to the very escalation the United States should seek to avoid.

Iran’s control of Iraqi militias is unclear

In part to compensate for its conventional military weakness, Iran has cultivated partnerships with various terrorist and militia groups in the region to project power, weaken regional rivals, and deter the United States from attacking Iran itself.66 Some of these relationships, like the one with Hezbollah, are decades-old. Others, such as those with Hamas, cross the Middle East’s sectarian divide and are driven more by a common adversary (Israel) than ideology. Iran’s financial, military, and political support to these groups is well-documented. The State Department’s 2020 Country Reports on Terrorism stated that Iran provided a combined $100 million a year to Palestinian terrorist groups based in Gaza and the West Bank.67 A segment of Hamas’s rocket inventory is powered by Iranian technology.68 In Iraq, more than twelve political parties are connected in some fashion to Iran, and the most powerful militia groups under the Iraqi government-affiliated PMF have pledged direct allegiance to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.69

But client-proxy relationships are complicated phenomena. A sponsor’s funding or arming of a proxy does not necessarily translate into the sponsor possessing command-and-control over a proxy’s decision-making.70 The United States has first-hand experience with how difficult it is to control a proxy. In Syria, despite U.S. military support, the armed Syrian opposition didn’t share the same priorities as the United States did, preferring to fight the Syrian government rather than ISIS.71 In Afghanistan, the approximately $90 billion spent training, arming, and equipping the Afghan security forces didn’t give the United States much influence over how the Afghan government behaved on matters like corruption and war policy against the Taliban.72

Iran runs into similar obstacles. Despite a years-long military and political relationship with Hamas, the Iranian government was apparently unaware of the group’s October 7 operation.73 Although U.S. officials frequently hold Iran ultimately responsible for Iraqi militia attacks on U.S. bases, the truth is that Iran doesn’t have full control over their operations—a common problem sponsors face with proxies in general.74 In Iraq, the militias backed by Iran have agency of their own and aren’t necessarily direct arms of the Iranian state. Even the militias most deeply associated with Iran, such as Katai’b Hezbollah and Asai’b Ahl al-Haq, have their own internal decision-making processes and agendas.75 Indeed in the past, the commander of the IRGC-Quds Force has sought to restrain the militias in order to prevent a wider conflict with the United States—and often fails.76 For all these reasons, assuming Iran is deliberately approving, let alone planning and executing, all of the attacks against U.S. troops in Syria and Iraq is dangerous. In the extreme, it could lead the United States to pursue actions, like a military strike on Iranian military personnel or territory, that would result in higher risk to U.S. forces in the region.

Escalation fuels more escalation

Graham and Brands’ proposals are wrong for another reason: taking the fight to Iran would be an escalatory action the Iranians would no doubt respond to. Iran has consistently retaliated whenever it perceives its interests to be under attack. Unlike the United States, which can pull back from the region and preserve its power at the same time, Iran is a principal actor in the Middle East and doesn’t have the luxury of withdrawing in the face of direct threats to its territory or economic interests. During the Trump administration, Iran sought to degrade the oil export capacity of its neighbors to penalize the United States for implementing a strategy of maximum pressure. In 2019, after the United States rescinded oil sanctions waivers for Iran’s top importers and designated the IRGC as a foreign terrorist organization, four oil tankers in the Persian Gulf were mined in what U.S. officials at the time called an Iranian-orchestrated attack.77 In May 2023, weeks after the United States seized a tanker carrying Iranian crude in violation of U.S. sanctions, Iran seized two oil tankers of its own.78 Iran has even retaliated against the United States for operations the United States did not conduct.79

If Iran was willing to retaliate for the seizure of a single vessel, the prospects of Iran retaliating in an even more forceful way to U.S. strikes on its oil industry or military personnel (as Graham and Brands advise) are high. U.S. troops in Syria and Iraq would be the most obvious targets of Iranian retaliation, just as they were in January 2020, when Iranian ballistic missiles caused severe injury to U.S. personnel in Iraq after the U.S. assassination of Soleimani. Back then, the United States wisely chose to deescalate. But the United States can’t assume de-escalation will occur in every instance. If even a single American was killed in an Iranian missile barrage, the pressure on any U.S. president to hold Iran accountable militarily would be high, which in turn would increase the chance of a regional conflict erupting. The United States would be put in the position of having to defend a constellation of bases in the Middle East, all which are within range of Iran’s ballistic and cruise missile stockpile. American casualties could be high, even after the deployment of land and sea-based anti-missile systems.

Stop turning U.S. troops into targets

Keeping U.S. troops in Syria and Iraq is high-risk and no-reward. The ISIS caliphate, the reason U.S. ground troops were deployed there in the first place, is destroyed. Whatever capability ISIS has left is no match for the pool of local actors who have the intent, interest, and capacity to combat them whether or not the United States maintains a presence. Far from being an asset, U.S. bases in Syria and Iraq are leverage points for its adversaries, who would be far less able to threaten the United States otherwise. Withdrawing from Syria and Iraq removes that leverage, reduces escalation risks for a wider war, and is a good first step toward a broader U.S. drawdown in the Middle East.

Endnotes

1 Daniel DePetris, “It is Time for U.S. Troops to Leave Syria,” Defense Priorities, May 10, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/it-is-time-for-us-troops-to-leave-syria; Jacob Knutson, “Where U.S. troops are stationed in the Middle East,” Axios, October 31, 2023, https://www.axios.com/2023/10/31/american-troops-middle-east-israel-palestine; Jeremy M. Sharp, Oman: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy, CRS Report No. RS21534 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2022), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RS/RS21534/116; Miriam Berger, “Where U.S. troops are in the Middle East and Afghanistan, visualized,” Washington Post, January 4, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/where-us-troops-are-in-the-middle-east-and-could-now-be-a-target-visualized/2020/01/04/1a6233ee-2f3c-11ea-9b60-817cc18cf173_story.html; Nathan J. Lucas and Brendan W. McGarry, United States Central Command, CRS Report No. IF11428 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2022), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11428; Ken Klippenstein and Daniel Boguslaw, “U.S. Quietly Expands Secret Military Base in Israel,” Intercept, October 27, 2023, https://theintercept.com/2023/10/27/secret-military-base-israel-gaza-site-512/; Ken Klippenstein, “Secret U.S. Military Presence in Yemen Adds a Twist to Houthi Attack on Israel,” Intercept, November 2, 2023, https://theintercept.com/2023/11/02/yemen-israel-us-troops/; “Al-Tanf, Syria,” International Crisis Group, November 23, 2023, https://www.crisisgroup.org/trigger-list/iran-usisrael-trigger-list/flashpoints/al-tanf-syria.

2 Mike Sweeney, “A Plan for U.S. Withdrawal from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, December 21, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-plan-for-us-withdrawal-from-the-middle-east.

3 Daniel L. Davis, “Debunking the Safe Haven Myth,” Defense Priorities, May 6, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/debunking-the-safe-haven-myth.

4 Paul Pillar, et al., “A New Paradigm for U.S. Policy in the Middle East: Ending America’s Misguided Policy of Domination,” Quincy Institute, https://quincyinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Ending-America’s-Misguided-Policy-of-Domination_FINAL_COMPRESSED.pdf.

5 Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “Protecting “The Prize”: Oil and the U.S. National Interest,” Security Studies 19, no. 3 (2010): 453–485.

6 Sam Heller, “Redefining Victory in America’s War Against the Islamic State in Syria,” War on the Rocks, January 5, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/01/redefining-victory-in-americas-war-against-the-islamic-state-in-syria/.

7 U.S. Department of Defense, “Statement from Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III on Deployment of USS Eisenhower Carrier Strike Group to the Eastern Mediterranean,” October 14, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3557560/statement-from-secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iii-on-deployment-of-uss-eis/.

8 C. Todd Lopez, “F-16s Head to Middle East to Help Protect U.S. Troops,” U.S. Department of Defense, October 24, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3567672/f-16s-head-to-middle-east-to-help-protect-us-troops/.

9 Knutson, “Where U.S. troops are stationed in the Middle East.” Jordan Freiman, “How the U.S. has increased its military presence in the Middle East amid Israel-Hamas war,” CBS News, November 6, 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-military-assets-in-middle-east/.

10 Natasha Bertrand, Katie Bo Lillies, and Alex Marquardt, “US and allies warn militant group Hezbollah against escalating Hamas-Israel conflict,” CNN, October 11, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/10/11/politics/us-allies-warn-hezbollah/index.html.

11 Maggie Fick, “Israel, Hezbollah trade fire across Israel-Lebanon border for third day,” Reuters, December 3, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/israel-hezbollah-trade-fire-across-israel-lebanon-border-third-day-2023-12-03/.

12 Ari Rabinovitch and Maytaal Angel, “Yemen’s Houthis say they launched missiles, drones at Israel,” Reuters, October 31, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/israel-warns-possible-hostile-aircraft-near-red-sea-city-eilat-2023-10-31/; Eric Schmitt, “Houthi Rebels Shot Down a U.S. Drone Off Yemen’s Coast, Pentagon Says,” New York Times, November 8, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/08/world/middleeast/yemen-houthi-us-drone.html.

13 U.S. Central Command, “Houthi Attacks on Commercial Shipping in International Water Continue,” December 3, 2023, https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/PRESS-RELEASES/Press-Release-View/Article/3605010/houthi-attacks-on-commercial-shipping-in-international-water-continue/; Sam Dagher, Mohammed Hatem, and Courtney McBride, “US In Talks With Gulf Allies on Military Action Against Houthis,” Bloomberg, December 8, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-12-08/us-in-talks-with-gulf-allies-on-military-action-against-houthis?embedded-checkout=true.

14 Carla Babb, “US Forces Attacked 151 Times in Iraq, Syria During Biden Presidency,” VOA, November 17, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/us-forces-attacked-151-times-in-iraq-syria-during-biden-presidency-/7360366.html; Michael Knights, Amir al-Kaabi, and Hamdi Malik, “Tracking Anti-U.S. Strikes in Iraq and Syria During the Gaza Crisis,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 5, 2023, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/tracking-anti-us-strikes-iraq-and-syria-during-gaza-crisis; Steven Beynon “5 Purple Hearts Awarded to Injured Troops After Spike in Attacks on Bases in Iraq, Syria,” Military.com, December 14, 2023, https://www.military.com/daily-news/2023/12/14/5-purple-hearts-awarded-injured-troops-after-spike-attacks-bases-iraq-syria.html.

15 Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Strikes Iranian-Linked Targets in Syria,” New York Times, October 26, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/26/us/politics/us-strikes-iran-syria-iraq.html; “U.S. airstrikes on Iran-backed targets in Syria kill at least 8 fighters, war monitor says,” CBS News, November 13, 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-airstrikes-iran-backed-targets-syria-at-least-8-fighters-dead/.

16 Haley Britzky and Natasha Bertrand, “US kills 5 Iran-backed militia members in drone strike in Iraq,” CNN, December 4, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/12/04/politics/us-forces-iran-backed-militia/index.html.

17 The White House, “Statement by the President on ISIL,” September 10, 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/09/10/statement-president-Isil-1.

18 Jim Sciutto, Jamie Crawford, and Chelsea J. Carter, “ISIS can ‘muster’ between 20,000 and 31,500 fighters, CIA says,” CNN, September 12, 2014, https://www.cnn.com/2014/09/11/world/meast/isis-syria-iraq/index.html.

19 United Nations, “In ISIL-controlled territory, 8 million civilians living in ‘state of fear’ – UN expert,” July 31, 2015, https://news.un.org/en/story/2015/07/505512.

20 Sarah Almukhtar, “ISIS Finances Are Strong,” New York Times, May 19, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/05/19/world/middleeast/isis-finances.html.

21 The Islamic State and Terrorist Financing, Testimony Before the Committee on Financial Services, United States House of Representatives, 113th Cong. (2014) (testimony of David S. Cohen, Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, Department of the Treasury), https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/hhrg-113-ba00-wstate-dcohen-20141113.pdf.

22 Sarah Almukhtar, Tim Wallace, and Derek Watkins, “ISIS Has Lost Many of the Key Places It Once Controlled,” New York Times, October 13, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/06/18/world/middleeast/isis-control-places-cities.html.

23 Maher Chmaytelli and Ahmed Aboulenein, “Iraq declares final victory over Islamic State,” Reuters, December 9, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-iraq-islamicstate/iraq-declares-final-victory-over-islamic-state-idUSKBN1E30B9.

24 U.S. Department of Defense, “U.S.-Iraq Joint Security Cooperation Dialogue Joint Statement,” August 8, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3487344/us-iraq-joint-security-cooperation-dialogue-joint-statement/.

25 Daniel DePetris, “Reset U.S. Syria Policy,” Defense Priorities, October 11, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/reset-us-syria-policy.

26 Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Disentangling from Syria’s Civil War: The Case for U.S. Military Withdrawal,” Defense Priorities, May 29, 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/disentangling-from-syrias-civil-war.

27 U.S. Department of State, “Special Online Briefing with Major General Matthew McFarlane, Commander, Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve,” August 16, 2023, https://www.state.gov/special-online-briefing-with-major-general-matthew-mcfarlane-commander-combined-joint-task-force-operation-inherent-resolve/.

28 “ISIS says its leader was killed by militants in Syria and names successor,” NBC News, August 3, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/isis-leader-killed-syria-abu-al-hussein-al-husseini-al-qurayshi-rcna98020.

29 “ISIS chief killed in Syria by Turkey’s intelligence agency, Erdogan says,” CBS News, April 30, 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/isis-leader-abu-hussein-al-qurashi-killed-erdogan-syria-turkey-intelligence-agency/.

30 United Nations, Thirty-second report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2610 (2021) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities, July 25, 2023, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N23/189/74/PDF/N2318974.pdf?OpenElement.

31 International Crisis Group, “Averting an ISIS Resurgence in Iraq and Syria,” October 11, 2019, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/eastern-mediterranean/syria/207-averting-isis-resurgence-iraq-and-syria.

32 U.S. Department of Defense, Operation Inherent Resolve and Other U.S. Government Activities Related to Iraq and Syria (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, November 9, 2023), https://media.defense.gov/2023/Nov/09/2003338020/-1/-1/1/OIR_Q4_SEP2023_FINAL_508.PDF.

33 Khaled al-Khateb, “Syrian forces crack down on Islamic State in Syrian desert,” July 2, 2022, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/06/syrian-forces-crack-down-islamic-state-syrian-desert.

34 Gil Barndollar, “Dealing With the Remnants of ISIS,” Defense Priorities, February 11, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/dealing-with-the-remnants-of-isis.

35 William Roebuck, “Keep US Troops in Syria,” Defense One, January 10, 2023, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2023/01/keep-us-troops-syria/381642/.

36 Jennifer Cafarella, “Don’t Get Out of Syria Assad’s Victory Will Only Lead to More Chaos,” Foreign Affairs, July 11, 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/syria/2018-07-11/dont-get-out-syria.

37 Peter D. Feaver and Will Inboden, “The Realists Are Wrong About Syria,” Foreign Policy, November 4, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/11/04/the-realists-are-wrong-about-syria/.

38 Worldwide Threat Assessment: Statement for the Record Before the Armed Services Committee, United States Senate, 117th Cong. (2021) (statement of Scott Berrier, Lieutenant General, U.S. Army, Director, Defense Intelligence Agency), https://www.dia.mil/articles/speeches-and-testimonies/article/2590462/statement-for-the-record-worldwide-threat-assessment-2021/.

39 Jeff Schogol, “Iran has attacked US troops 83 times since Biden became president ,” Task and Purpose, March 28, 2023, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/iran-attacks-us-military-iraq-syria-biden/.

40 Knights, al-Kaabi, Malik, “Tracking Anti-U.S. Strikes in Iraq and Syria During the Gaza Crisis.”

41 Nasser Karimi, Amir Vahdat And Jon Gambrell, “Iran strikes back at US with missile attack at bases in Iraq,” January 7, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/ap-top-news-persian-gulf-tensions-tehran-international-news-iraq-add7a702258b4419d796aa5f48e577fc.

42 Peter Baker, Eric Schmitt and Michael Crowley, “An Abrupt Move That Stunned Aides: Inside Trump’s Aborted Attack on Iran,” New York Times, September 21, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/21/us/politics/trump-iran-decision.html.

43 Benjamin H. Friedman, “Don’t Fear Vacuums: It’s Safe to Go Home,” Defense Priorities, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/dont-fear-vacuums-its-safe-to-go-home.

44 Yerevan Saed, “Iraq Deepens Ties With GCC Neighbors,” Arab Gulf States Institute, April 12, 2023, https://agsiw.org/iraq-deepens-ties-with-gcc-neighbors/.

45 The Trump Administration’s Syria Policy: Perspectives from the Field: Statement for the Record Before the Subcommittee on National Security Committee on Oversight and Reform, United States House of Representatives 116th Cong. (2019) (statement of John Glaser, Director of Foreign Policy Studies, Cato Institute), https://www.congress.gov/116/meeting/house/110125/witnesses/HHRG-116-GO06-Wstate-GlaserJ-20191023.pdf.

46 Jonathan Mercer, Reputation and International Politics (Cornell, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996).

47 Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Cornell, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005).

48 Samya Kullab And Qassim Abdul-Zahra, “US dismisses Iraq request to work on a troop withdrawal plan,” January 10, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/182bae76452d7565b0a3d840ff0369cb.

49 The White House, “Letter to the Speaker of the House and President pro tempore of the Senate consistent with the War Powers Resolution (Public Law 93–148),” October 27, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/10/27/letter-to-the-speaker-of-the-house-and-president-pro-tempore-of-the-senate-consistent-with-the-war-powers-resolution-public-law-93-148-4/.

50 U.S. Department of Defense, “A Senior Defense Official and a Senior Military Official Hold a Background Briefing on Self-Defense Strikes in Syria,” October 26, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/3571452/a-senior-defense-official-and-a-senior-military-official-hold-a-background-brie/.

51 Knights, al-Kaabi, Malik, “Tracking Anti-U.S. Strikes in Iraq and Syria During the Gaza Crisis.”

52 Jeff Seldin, “Iran-Backed Militias Respond to US Strike with More Attacks,” VOA, November 9, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/iran-backed-militias-respond-to-us-strike-with-more-attacks-/7348976.html.

53 Michael Knights, “Deterring Militias in Iraq: What Works and What Doesn’t,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, June 28, 2021, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/deterring-militias-iraq-what-works-and-what-doesnt.

54 Raghda Elbahy, “Deterring violent non-state actors: dilemmas and implications,” Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Sciences 1, no. 1 (2019): 43–54.

55 Eitan Shamir, “Deterring Non-State Actors,” in NL ARMS Netherlands Annual Review of Military Studies 2020, ed. Frans Osinga and Tim Sweijs (NL ARMS), 263–286.

56 Isabel Coles and Michael R. Gordon, “U.S. Warns Iraq It Is Preparing to Shut Down Baghdad Embassy,” Wall Street Journal, September 27, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-warns-iraq-it-is-preparing-to-shut-down-baghdad-embassy-11601238966.

57 Phil Stewart, Idrees Ali and Ahmed Rasheed, “US forces under fire in Middle East as America slides towards brink,” Reuters, November 9, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/us-forces-under-fire-middle-east-america-slides-towards-brink-2023-11-09/.

58 U.S. Department of Defense, “Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III’s Call With Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani,” December 8, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3612418/secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iiis-call-with-iraqi-prime-minister-mohamme/.

59 Daniel DePetris, “‘Maximum Pressure’ Harms Diplomacy and Increases Risks Of War With Iran,” Defense Priorities, November 19, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/maximum-pressure-harms-diplomacy-and-increases-risks-of-war-with-iran.

60 Fabian Hinz, “Little and large missile surprises in Sanaa and Tehran,” October 17, 2023, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/military-balance/2023/10/little-and-large-missile-surprises-in-sanaa-and-tehran/.

61 Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community (Washington, DC: Director of National Intelligence, February 6, 2023), https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2023-Unclassified-Report.pdf.

62 Barry R. Posen, “Courting War,” Boston Review, March 3, 2020, https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/barry-posen-courting-war/.

63 “Meet the Press – October 15, 2023,” NBC News, October 15, 2023, https://www.nbcnews.com/meet-the-press/meet-press-october-15-2023-n1307411.

64 Hal Brands, “US Must Press Its Advantages Over Iran or War Will Spread,” Bloomberg, October 21, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-10-21/israel-hamas-latest-us-should-punish-iran-for-proxies-attacks#xj4y7vzkg.

65 C-SPAN, “State and Defense Department Officials Testify on U.S. Support for Israel,” November 8, 2023, https://www.c-span.org/video/?531702-1/state-defense-dept-officials-testify-us-support-israel.

66 Thomas Juneau, “How War in Yemen Transformed the Iran-Houthi Partnership,” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, July 30, 2021, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1057610X.2021.1954353.

67 U.S. Department of State, Country Reports on Terrorism 2020 (Washington, DC: Department of State), https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2020/.

68 Fabian Hinz, “Iran Transfers Rockets to Palestinian Groups,” Wilson Center, May 20, 2021, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/irans-rockets-palestinian-groups.

69 Andrew Hanna and Garrett Nada, “Iran’s Roster of Influence Abroad,” Wilson Center, March 24, 2020, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/irans-roster-political-influence-abroad-0.

70 Assaf Moghadam and Michel Wyss, “Five Myths about Sponsor-Proxy Relationships,” Lawfare, December 16, 2018, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/five-myths-about-sponsor-proxy-relationships.

71 Sam Heller, “Suppose America Gave a Proxy War in Syria and Nobody Came?” Century Foundation, July 7, 2016, https://tcf.org/content/report/suppose-america-gave-proxy-war-syria-nobody-came/.

72 Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction, Why the Afghan Security Forces Collapsed (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, February 2023), https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/evaluations/SIGAR-23-16-IP.pdf.

73 U.S. Department of State, “Department Press Briefing – October 10, 2023,” October 10, 2023, https://www.state.gov/briefings/department-press-briefing-october-10-2023/.

74 Daniel Byman, “Are Proxy Wars Coming Back?” Washington Quarterly 46, no. 3 (Fall 2023): 149–164.

75 Erica Gaston and Douglas Ollivant, “U.S.-Iran Proxy Competition in Iraq,” New America, February 20, 2020, http://newamerica.org/future-security/reports/us-iran-proxy-competition-iraq/.

76 Qassim Abdul-zahra And Samya Kullab, “Iran’s allies on high alert in Trump’s final weeks in office,” Associated Press, November 20, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-donald-trump-iran-middle-east-baghdad-7532d20c40b9d1240c77f26f621d2902.

77 Vivian Yee, “Claim of Attacks on 4 Oil Vessels Raises Tensions in Middle East,” New York Times, May 13, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-oil-tanker-sabotage.html.

78 “US Confirms April Seizure of Iran Oil Shipment” VOA, September 8, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/us-confirms-april-seizure-of-iran-oil-shipment-/7260671.html.

79 Eric Schmitt and Ronen Bergman, “Strike on U.S. Base Was Iranian Response to Israeli Attack, Officials Say,” New York Times, November 21, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/18/world/middleeast/iran-drone-al-tanf-syria.html.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News