- Iran is capitalizing on the widening rift between several post-coup leaders in the Sahel and Western countries, including the United States and France.

- Iranian leaders perceive that expanded relations with Africa’s leaders can help Iran circumvent U.S.-led sanctions and enhance Iran’s role as a supplier of sophisticated weaponry, particularly armed drones.

- Iran’s position on the Mideast crisis and U.S. and Western policies more broadly resonates with many countries in Africa and throughout the Global South.

- Iran has taken sides in the civil conflict in Sudan to try to expand Iranian influence on the Red Sea and outflank some of the Arab states aligned with the United States.

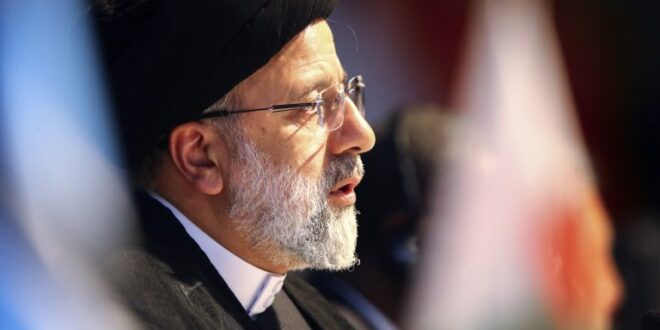

Iran is expanding its relations with leaders in the Sahel to achieve several overlapping objectives. In the context of the post-October 7 Mideast crisis, Iran is capitalizing on the resonance of its active efforts to derail Israel’s offensive in the Gaza Strip – actions that are drawing support in Africa and elsewhere in the Global South. The Gaza crisis has intersected with the seizure of power by several military leaders in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger – all of whom are distancing themselves from Western powers, particularly the United States and France. Seeking to step into that void, Iran has affirmed its support for the juntas now leading those states. The confluence of the Mideast crisis with the accession to power of several leaders well-disposed towards Iran, Iran’s “Axis of Resistance,” and Iranian partners such as Russia provides a unique moment for Tehran to counter efforts by the United States and its allies to isolate Iran and weaken it through comprehensive economic sanctions. As part of a renewed outreach to Africa’s leaders, in July 2023, Iran’s President Ibrahim Raisi visited Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Kenya and “praised the resistance of African countries against colonization as a symbol of their awakening and vigilance.” He did not visit Mali, Burkina Faso, or Niger on his regional swing, but in September, Raisi praised “the resistance of these [post-coup] African countries” in the face of “hegemonic European policies and colonialism.”

Iran’s leaders have stressed their ideological alignment with Sahelian leaders, but many experts see ideology and diplomatic engagement as secondary to the strategic advantages Iran perceives as newly available. The post-coup leaders have taken concrete steps to distance their countries from colonial power France and from the United States, echoing Tehran’s accusations that the Western powers are exploiting African and other Global South populations for their self-interest. In January 2023, following its seizure of power four months earlier, the military junta ruling Burkino Faso ordered the 400 French special forces stationed in the West African country, deployed to battle groups to counter terrorist organizations affiliated with Al Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS), to leave within a month. In late January 2024, at the ceremony to receive the credentials of the new ambassador of Burkina Faso to Iran, President Raisi indirectly referenced the Israel- -Hamas war as a point of unity between Tehran and Ouagadougou, stating: “Countries like the United States and some Western governments and the Zionist regime, which claim the most to fight terrorism, are the main source of terror and terrorist groups, as today we witness the crimes and acts of official and state terrorism of the Zionist regime with the support of the Americans and some western countries.”

Similarly, Mali provided an opening for Iran, and its strategic partner Russia, to expand their influence in Africa by distancing itself from the former colonial power, France. Following the deterioration of ties with Bamako after military coups there in 2020 and 2021, in August 2022, France completed the withdrawal of the 2,400 forces performing Operation Barkhane against terrorist groups linked to Al Qaeda. France had initially intervened in the country at the request of Bamako in 2013 to respond to an offensive by the Al Qaeda-allied ethnic Tuareg separatist movement in the country’s north. Seizing on the French departure that same month, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian visited Bamako, where he spoke about Mali’s “significant status” in Tehran’s foreign policy and his “confidence about a new chapter in fresh Tehran-Bamako ties.” In May 2023, as Iran sought to convince Malian officials to view the Islamic Republic as a reliable partner in this struggle against Sunni jihadist groups that have committed many attacks in the country, Mali’s Defense Minister, Colonel Sadio Camara, visited Iran reportedly to discuss the possible purchase of Iranian arms. According to Iranian state-run media, Iranian Defense Minister Mohammad Reza Ashtiani “expressed the country’s readiness to provide Mali with military equipment and experiences in the fight against terrorism.” The meetings raised expectations that Iran sought to utilize its new friendship with Mali to further Tehran’s ambitions to become a major arms supplier to countries in the Global South, many of which are disqualified – due mainly to human rights practices and coup-related seizures of power – from receiving Western weaponry. Ashtiani was quoted as offering to share Iranian equipment, experiences and capabilities in training with Mali, stating: “The Islamic Republic of Iran will spare no effort to strengthen Mali’s defense power against the threats posed by terrorist groups.” Iran has been providing its armed drones to guerrilla groups across the Middle East for decades, and the Russian purchase and use of Tehran’s Shahed drones against Ukraine has expanded African and other interest in the Iranian systems.

After they left Mali, French troops re-deployed to Niger as their Sahelian hub but, to Iran’s benefit, both Paris and Washington suffered the same setbacks there as they have in Burkina Faso and Mali. Following a coup there in July 2023 that ousted President Mohamed Bazoum, French troops departed the country in September. In March, Niger’s junta announced they were terminating a counterterrorism pact with the United States, under which 1,000 U.S. forces helped combat Al Qaeda and IS affiliates. The junta cited as justification for the expulsion what it said were false U.S. claims Niger was offering Iran access to its uranium supplies. U.S. officials subsequently engaged in talks with the Niger leadership to salvage the counter-terrorism cooperation, but the future of the U.S. mission there is uncertain. Seeking to capitalize on Niger’s turn against the Western powers, and largely skirting the accusations it seeks uranium supplies in Niger, Iran said in late January it is willing to help the country overcome international sanctions. Meeting with Niger’s Prime Minister Ali Mahaman Lamine Zeine on January 24, Iran’s first vice-president, Mohammad Mokhber, said Iran condemns “the cruel sanctions that are imposed by the domination system.” Hoping to use its newfound influence in Niamey to help circumvent U.S. sanctions, he added: “We will definitely share the experiences we have in this field with our brothers” from Niger.

Further east on the continent, Iranian strategists are pushing to take advantage of the yearlong civil conflict between contending military factions in Sudan. The war provided Iran with an opening to rebuild diplomatic relations with the Khartoum government in October 2023 – for the first time since 2016 – and to press for strategic access to Port Sudan, which the Sudan Armed Forces control. A decade ago, Iran was able to use Sudan as a conduit through which to move arms to Hamas and Palestine Islamic Jihad in the Gaza Strip. Tehran lost that access as Sudan’s military leaders turned toward lucrative relationships with the wealthy Arab Gulf states, particularly the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Qatar, which competed with each other for influence with Khartoum. Sudan also engaged with Washington to obtain removal from the U.S. list of terrorism state sponsors (“terrorism list”) and agreed to normalize ties with Israel under the Trump Administration-brokered “Abraham Accords.” In February 2024, reports surfaced that Iran is supplying sophisticated armed drones to the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) for use against its rival, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia. Tehran calculates that, should it help the Armed Forces prevail in the civil conflict, Iran will be rewarded with renewed access to Port Sudan and other strategic benefits. The use of the port there would enable Iran to increase assistance to its Axis of Resistance ally on the eastern side of the Red Sea, the Houthi movement in Yemen, to pressure Israel and the United States by impeding maritime commercial traffic. Yet, a successful Iranian effort to exert a stranglehold on Red Sea traffic would greatly increase the chances that Washington escalates significantly against both Iran and the Houthis actors in order to ensure the freedom of navigation through the key waterway.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News