Key Takeaway: Russian Africa Corps soldiers deployed to Niger on April 12, which will challenge US efforts to remain in Niger in the immediate term—undermining the West’s counterterrorism posture in West and North Africa—and create long-term opportunities for the Kremlin to create conventional and irregular threats that strategically pressure Europe. The Africa Corps contingent in Niger will likely remain small in the coming months because it lacks the capacity for a bigger deployment due to recruitment issues. This small footprint will enable Russia to strengthen its influence in Niger and consolidate its logistical network in Africa without significantly affecting the rapidly escalating al Qaeda and Islamic State insurgencies in Niger. Greater Russian influence and military presence in Niger in the coming years will create several future opportunities for the Kremlin to strategically threaten Europe with energy blackmail, migration influxes, and conventional military threats.

Assessments:

Russian Africa Corps soldiers deployed to the Nigerien capital on April 12, which will immediately challenge US efforts to remain in Niger and undermine America’s counterterrorism posture in West and North Africa. One-hundred Africa Corps troops arrived in Niamey to train Nigerien forces as part of Nigerien-Russian military cooperation agreements signed in December 2023 and January 2024.[1] A Kremlin-affiliated milblogger claimed that the Russian Ministry of Defense had planned the deployment of Africa Corps personnel for months and influenced Niger’s decisions to distance itself from its Western partnerships.[2] CTP had assessed that the junta may be planning to deploy Russian soldiers since the meetings between Nigerien junta leaders and Yevkurov in Moscow in January 2024.[3]

Africa Corps’s arrival will exacerbate tensions between the United States and the Nigerien junta, undermining US efforts to remain in Niger and setting conditions to replace US forces. The Nigerien junta annulled defense cooperation with the United States on March 16, threatening the continued presence of 700 US troops operating out of the US drone base in northern Niger.[4] Niger said the United States agreed to outline a disengagement plan on March 27, but US officials still say the future of US troops in Niger is unclear.[5]

US officials have also voiced concerns about growing Nigerien military cooperation with Russia in 2024, and they gave broad public warnings to regional states to avoid collaborating with Russian mercenaries.[6] The Africa Corps contingent brought a “latest generation” air defense system that the Nigerien government and Africa Corps claim is intended to provide better protection of Nigerien airspace.[7] The United States has signaled it will be strongly against this deployment, and Niger’s move to acquire anti aircraft systems directly enables the Nigerien junta to ground US drones and effectively force US forces out of the country unless they reach a new agreement.

The Africa Corps troops said they wanted to take over the US base in Agadez, northern Niger, minutes after landing in Niamey, indicating they seek to replace the United States.[8] Russia could do this through further discussions with the Nigerien junta or rousing public opinion against a continued US presence to force the junta’s hand. Pro-junta and pro-Russian networks in Niger quickly circulated calls for demonstrations against the United States on April 13, hours after Africa Corps’s arrival.[9] Russia has also used its conventional and irregular footprint in Syria to threaten and undermine US forces operating against Islamic State militants, underscoring the threat of the Russian military presence near US and allied areas of operation.[10] Russian forces in Mali have backfilled vacated French and UN bases across the country, establishing a precedent of directly backfilling Western positions after they withdraw.[11]

A US withdrawal from Niger would undermine America’s counterterrorism posture in West and North Africa despite potential fallback options, which could increase the transnational threat risk to Europe and the United States. US Africa Command head Gen. Michael Langley warned that the loss of US basing in the Sahel will “degrade our ability to do active watching and warning, including for homeland defense.”[12] The increased terror-attack threat level in Europe and the United States highlights the potential risk of losing such capabilities.[13] African affiliates have created networks that facilitate the travel of foreign fighters between the Sahel and southern Europe via North Africa.[14] Such activity raises the risk of African affiliates contributing to external attack plots, although non-African affiliates continue to pose the greatest external threat.[15]

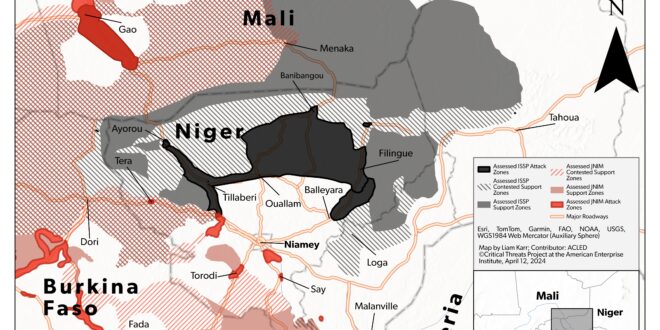

The United States is exploring alternative basing options in the Gulf of Guinea, but these potential locations have practical drawbacks. The Wall Street Journal reported on January 3 that the United States held preliminary talks for US reconnaissance drones to use airfields in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana.[16] American forces at the Agadez Air Base use MQ9 Reaper drones, which have a 1,150-mile range.[17] This range means that prospective US bases in the Gulf of Guinea would be unable to surveil Salafi-jihadi cells and networks in Libya and most of Algeria. Drones in Côte d’Ivoire would also be too far west to surveil the Lake Chad Basin in northeastern Nigeria, where the Islamic State’s West Africa Province and regional administrative node is based.

Figure 1. Current and Prospective Range of United States Intelligence, Reconnaissance, and Surveillance Capabilities in Northwestern Africa

Note: CTP calculated the alternative ranges using the 1,150-mile range of the MQ9 Reaper drones that US forces use in Niger. CTP then centered these range rings on the northernmost military-use airport in each country where the US is reportedly exploring alternative basing, in the event it withdraws from Niger.

The Africa Corps deployment will immediately enable Russia to strengthen its influence in Niger and consolidate its logistical network in Africa. Africa Corps personnel in Niger will grow relationships between Nigerien soldiers and the Nigerien junta, enabling Russia to pursue one of its goals of securing access to natural resources. Russian state news outlet RIA Novosti said the Africa Corps deployed to “build relationships and jointly form and train the Nigerien army.”[18] Russia previously lacked strong intrapersonal ties with the Nigerien junta, as most Nigerien officers trained with the French or US armies.[19] Russia’s mercenary deployments have repeatedly sought to build these kinds of intrapersonal relationships in other countries to grow Russian influence over authoritarian regimes and gain access to natural resource concessions.[20]

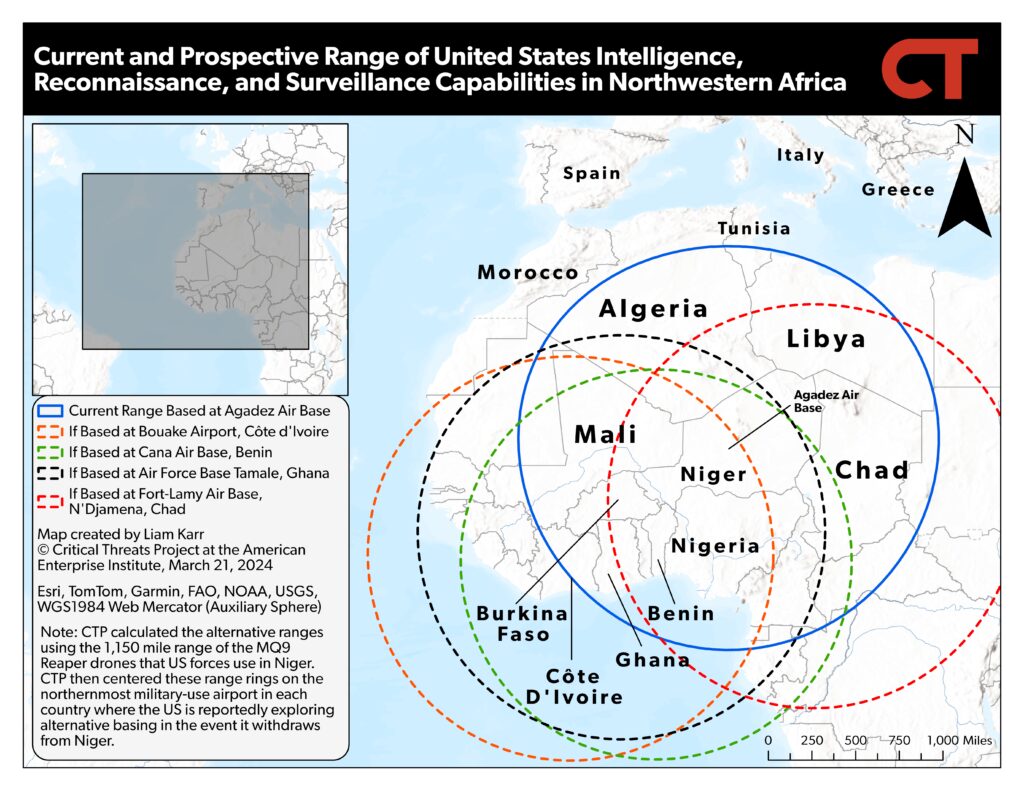

An Africa Corps base in Niger will also strengthen Russia’s logistical network in Africa by bridging the air gap between its North African and sub-Saharan positions. Africa Corps taking over the US base in Agadez would put a Russian base 1,100 miles or less from the Russian-controlled air bases in Libya to the north and just over 1,100 miles from major Russian bases in the Malian capital to the west and the Central African Republic capital to the southeast.[21]

Figure 2. Russian Mercenary Facilities in Northwest Africa

Note: At the time of publishing, US forces are still stationed at Agadez Air Base.

The Africa Corps contingent in Niger will likely remain small in the coming months because it lacks the capacity for a bigger deployment due to recruitment issues. A Kremlin-affiliated milblogger said the Russian Ministry of Defense had already delayed Africa Corps’s initial deployment to Niger due to recruiting issues.[22] The Kremlin halved its initial recruiting goal of 40,000 soldiers in the immediate aftermath of subsuming Wagner Group operations in August 2023 to just 20,000 by the end of 2023, but it still failed to meet the adjusted goal.[23] Africa Corps deployed a similarly sized 100-soldier contingent to neighboring Burkina Faso in January 2024 and said the group’s size would eventually grow to 300 soldiers.[24] However, there have been no reports of more troops arriving since then. This lull highlights that the process of scaling up these smaller deployments is a monthslong, if not yearslong, process.

The small Africa Corps deployment in Niger will be unable to address the rapidly escalating Salafi-jihadi insurgency. Even a scaled-up force during the coming year will almost certainly fail to improve the deteriorating security situation, especially in the event of a US withdrawal. Africa Corps is still carrying out recruiting efforts, and its numbers are slowly rising, which will enable it to scale up troop deployments in the coming years.[25] The group has targeted former Wagner fighters, Russian military veterans, and military-fit Russian residents to fill a variety of roles through its Telegram channel since December 2023 and has amplified these efforts since March 2024.[26] These advertisements brand the Africa Corps service as a chance to gain a stable Ministry of Defense–provided salary with medical and life insurance benefits.[27]

Russian mercenaries in Africa have been ineffective—if not counterproductive—in counterinsurgency operations. Wagner Group forces failed to slow the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in Mozambique in 2019, and the 1,000–2,000 Russian soldiers in Mali have not degraded the insurgency there.[28] Russian soldiers’ brutal tactics are also counterproductive, as they exacerbate human rights abuses against civilians that insurgent groups use to gain popular support.[29]

Niger will lose crucial US-backed equipment, training, and support programs if it ends cooperation with the United States. The United States has provided three C-130H Hercules transport aircraft, two Cessna-208 Caravan light transport aircraft, and at least 50 Mamba 7 armored personnel carriers to the Nigerien military since 2012, making it the leading provider for the Nigerien military over this period.[30] The end of US maintenance, spare-part provision, and training programs will slowly degrade the usability of more sophisticated systems like transport aircraft.[31] US forces in Niger have also trained Nigerien forces; provided intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) in support of Nigerien operations; and advised and assisted Nigerien troops on rare occasions.[32] The decrease in Western ISR support in the Sahel has significantly improved Salafi-jihadi militants’ freedom of movement, enabling militants to gather in larger numbers and attack security forces with less warning, increasing the scale and severity of their attacks.[33]

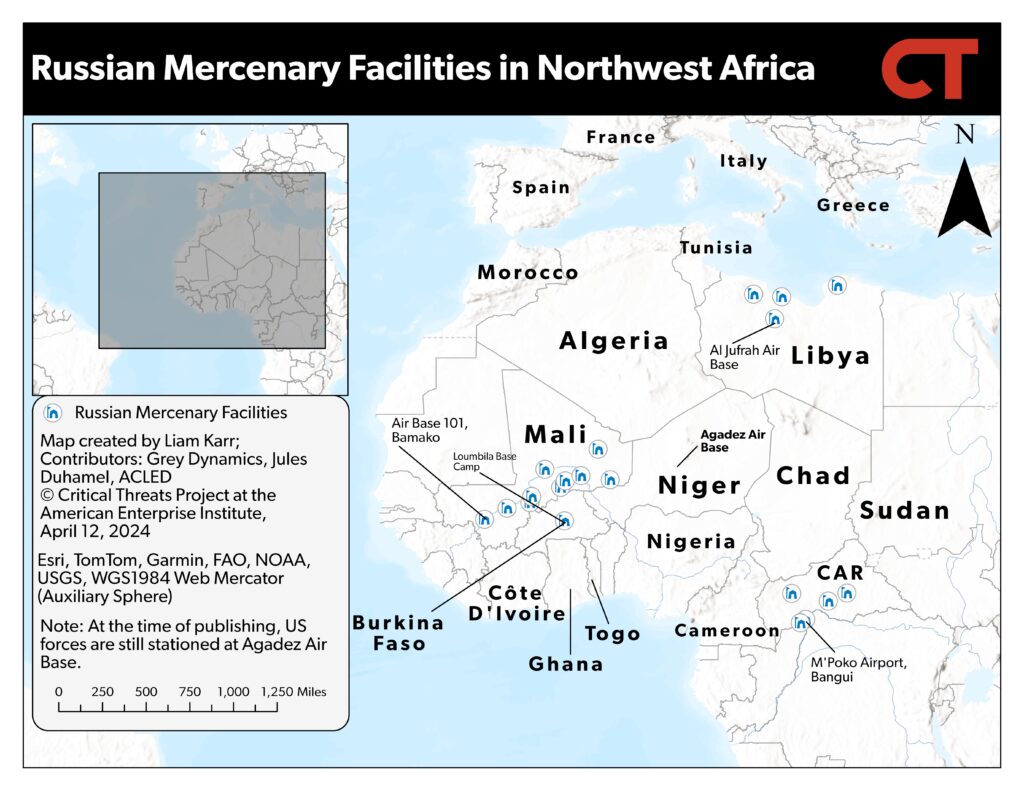

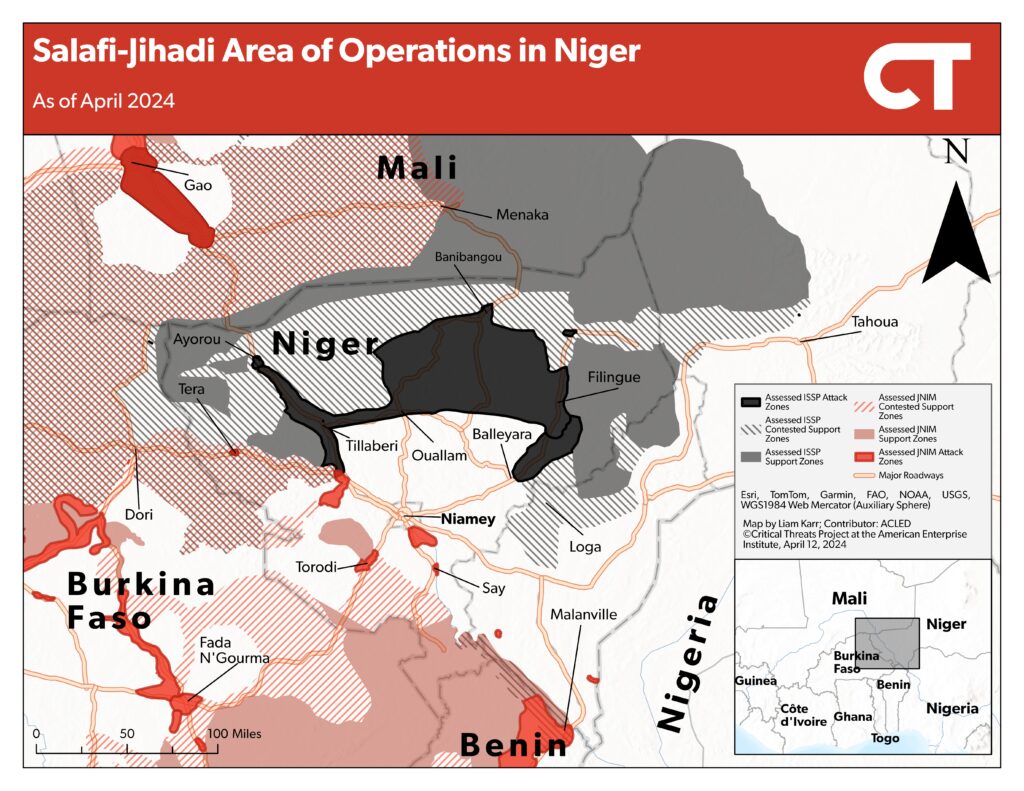

The regional Islamic State and al Qaeda affiliates are rapidly strengthening and expanding their activity closer to the Nigerien capital. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen, has doubled its number of attacks in southwestern Niger in the first quarter of 2024, compared to the last quarter of 2023, as it establishes new support zones and encroaches on key roads around the capital.[34] The group claimed one attack within one mile of the capital city limits.[35] The Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISSP) killed more than twice the number of Nigerien soldiers and civilians during the last five months of 2023 than it did in the first seven months before the coup.[36] The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project and local reports on X (Twitter) also noted that ISSP expanded the rate and geographic scope of its tax collection activities, showing growing control in parts of western Niger.[37]

Figure 3. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in Niger

Greater Russian influence and military presence in Niger will create several long-term opportunities for the Kremlin to strategically threaten Europe with energy blackmail, migration influxes, and conventional military threats. Russian access to the large uranium deposits in Niger in exchange for Russian military support would grow Russia’s share of the nuclear energy market, increasing its leverage with countries seeking to cut Russian energy purchases.[38] Niger is the seventh-largest uranium producer in the world and has one active major uranium mine.[39] The mine provided about 2,020 tons of uranium in 2022, which is equal to about 5 percent of the world’s mining output.[40] France could be particularly vulnerable as it relies on nuclear energy for 68 percent of its electricity and has relied on Niger for nearly 20 percent of the uranium it imports to power its nuclear energy facilities over the past decade, although France has tried to diversify its suppliers in recent years.[41]

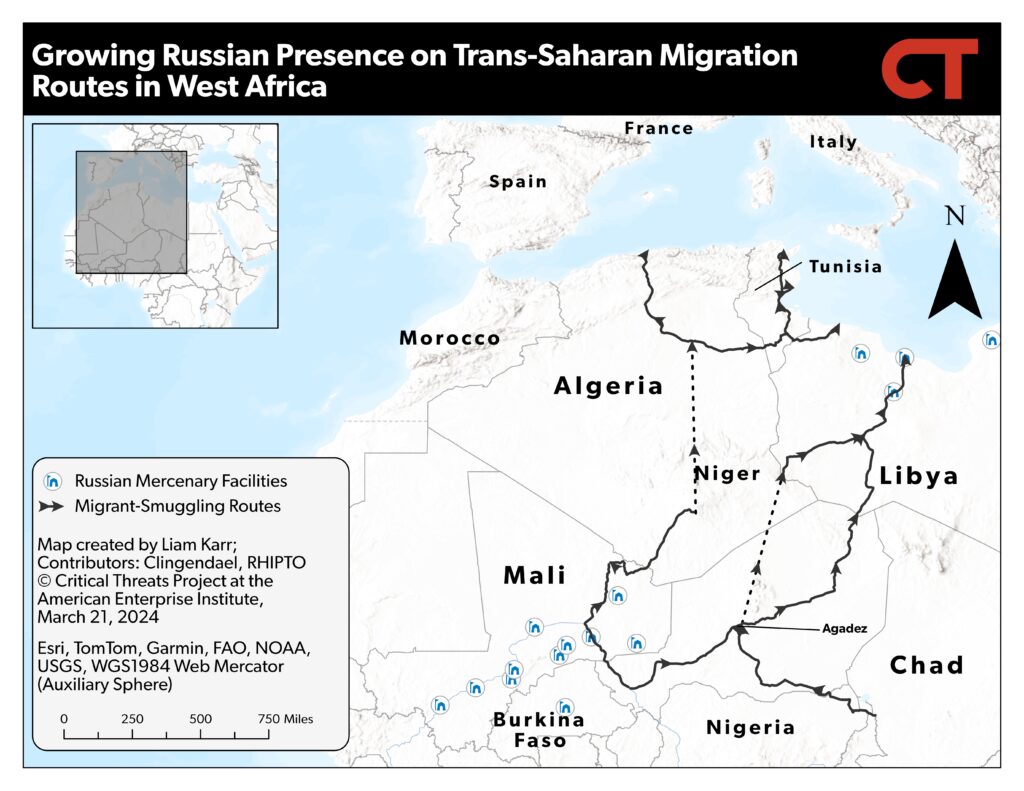

Russia would also likely use positions in northern Niger to exploit trans-Saharan migrant-smuggling routes to increase irregular migration flows to Europe and enrich its mercenaries. The EU border patrol agency and numerous European officials have warned in 2024 that Russian President Vladimir Putin is attempting to foment greater refugee flows from Africa to destabilize Europe, influence elections, and undermine support for Ukraine.[42] Russia has repeatedly and systematically weaponized migrant crises in Europe. The Russian and Belarussian governments have flooded the borders of Finland, Lithuania, and Poland with refugees since 2021.[43] Their tactics included luring refugees from the Middle East and Africa on flights to Europe based on false promises before dropping them at the border.[44] The Kremlin also foments prolonged instability in theaters where it is active, such as Syria, Ukraine, and now the Sahel, which creates long-term refugee crises.[45]

Russia now has a military presence along many of the trans-Saharan migrant routes, increasing its opportunities to facilitate mass migration. Russian mercenaries in the Sahel have contributed to a massive spike in human rights abuses since 2021, helping fuel record-high levels of trans-Saharan migration to Europe.[46] The EU border patrol agency noted that 380,000 migrants attempted to cross into Europe from Libya in 2023, the highest number of irregular crossings since 2016.[47] Russia’s partners in the Nigerien junta annulled an EU-backed migration law that aimed to stem these flows in December 2023, benefiting both allies but directly increasing migrant flows to North Africa and Europe.[48] Russia’s growing footprint in sub-Saharan Africa also increases opportunities for Russian personnel to directly lure more migrants to Europe to drop at NATO’s borders.

Figure 4. Growing Russian Presence on Trans-Saharan Migration Routes in West Africa

Russian mercenaries in Niger can insert themselves into the local migrant-smuggling economy to further increase profits and migrant flows. Facilitating migration to North Africa is a major local economy in northern Niger, and Agadez is a primary staging point for migration routes to the Libyan coast.[49] Nigerien security forces are already involved in the migrant-smuggling economy by charging migrant smugglers at security checkpoints and escorting migrant convoys.[50] Russian mercenaries have shown adept at inserting themselves into other informal African economies by cultivating ties with civilian and military power brokers; they will do the same in Niger.[51] This would allow them to both profit off migration and directly facilitate migration by helping convoys reach the Mediterranean.

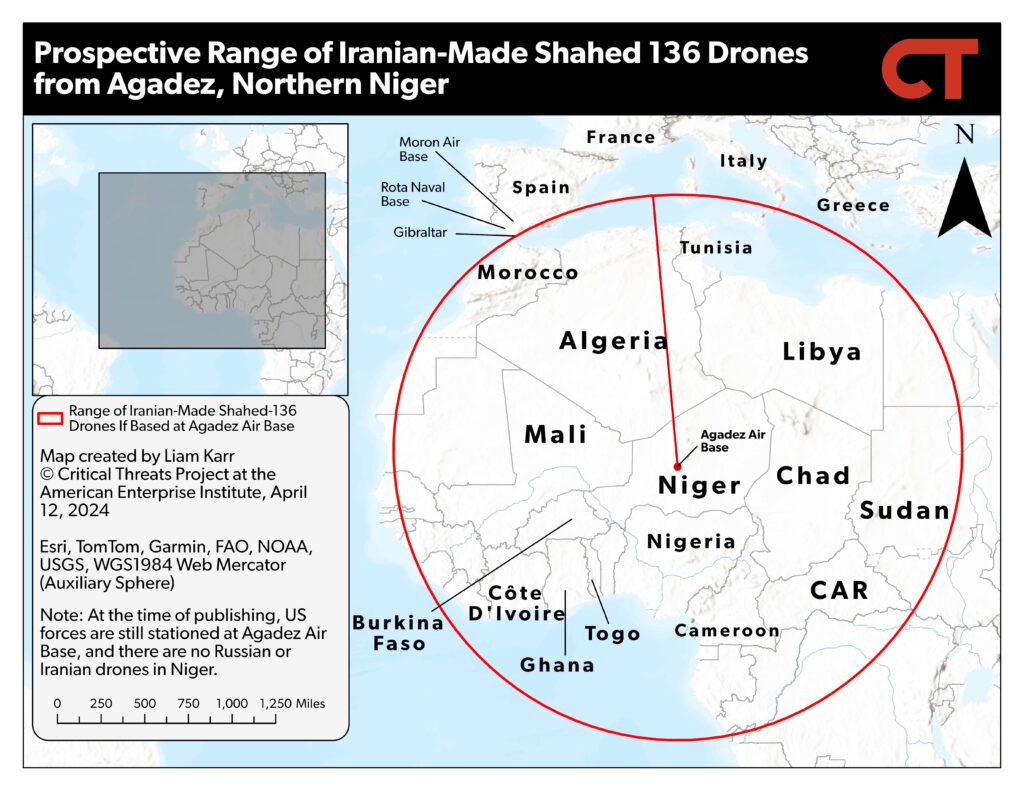

Russia is unlikely to base drones with its mercenaries in Niger in the immediate term. However, the presence of Russian mercenary bases in northern Niger would create an opportunity for the Kremlin to deploy drones in the area to threaten NATO’s southern flank in the future. Russian mercenaries in Mali have not deployed or indicated they plan to deploy Russian drones in Africa. Wagner auxiliaries in Mali have relied on Malian forces’ use of Turkish TB2 drones.[52] Niger also has its own TB2 drones.[53] Russia has supported its Wagner mercenaries in Libya with conventional Russian aircraft but no drones.[54] The rapid increase in Iranian and Russian production of Shahed-style drones for Russia’s war in Ukraine increases the risk that the Kremlin leverages some of this production capacity to equip mercenaries in Africa with drones in the future.[55]

Shahed 136 drones based near Agadez would be within range of key US and NATO installations and parts of the Mediterranean Sea. The Shahed 136, also known as Geranium in Russia, has a maximum range of 1,553 miles (2,500 kilometers).[56] Agadez is 1,523 miles from Sicily, Italy, and the southern tip of the Italian mainland; 1,555 miles from Gibraltar, UK’s overseas territory on the Iberian Peninsula; and roughly 1,600 miles from the US-Spanish air and naval bases in southern Spain.

Figure 5. Prospective Range of Iranian-Made Shahed 136 Drones from Agadez, Northern Niger

Note: At the time of publishing, US forces are still stationed at Agadez Air Base, and there are no Russian or Iranian drones in Niger.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News