Key points

In addition to the 51 allies the United States is obligated by treaty to defend, it has a number of quasi-allies: states the United States is not committed to defend but to which it provides a substantial degree of military and political support.

By creating uncertainty about U.S. commitments both at home and abroad, quasi-allies’ ambiguous status creates dangers for both the United States and the quasi-allies.

For the United States, the danger is entanglement; having quasi-allies can pull the United States into trouble outside its core interests, creating needless cost, risk, and even war.

Quasi-allies may suffer a kind of moral hazard; they may falsely believe they have U.S. military protection and fail to secure themselves sufficiently or become emboldened and dangerously provoke adversaries.

U.S. leaders should be more wary of these dangers and avoid loose talk and policy acts that imply a commitment to non-allies’ defense.the problem of quasi-allies

An ally is a state that a first state has made a formal defense commitment to defend via treaty, or one it fights alongside in a war, like the Allied Powers in the World Wars.1 By this definition, the United States is allied with more than one-fourth of the world’s countries. There are a variety of problems with having so many allies, especially maintaining permanent alliances, as opposed to the temporary sort used to fight wars. This paper, however, is about a narrower problem: confusing or broadening the definition of an ally by suggesting that the U.S. might defend states it has no commitment to defend.

Putting states into this ambiguous status, what we call “quasi-allies,” is dangerous, both for the United States and those states. By intimating it may defend states it has no official commitment or intention to—and more importantly, has no vital interest in defending—U.S. leaders risk entanglement in other nations’ troubles, taking on needless cost and risk, and even fighting pointless wars.

Quasi-allies may also suffer because of their uncertain status—they may underestimate their risk because they think the United States will rescue them if they run into trouble. One potential result is policies or negotiating stances that lead to these would-be allies being threatened or attacked. Another consequence of misplaced reliance on U.S support might be underinvestment in defense.

Who are U.S. allies and quasi-allies

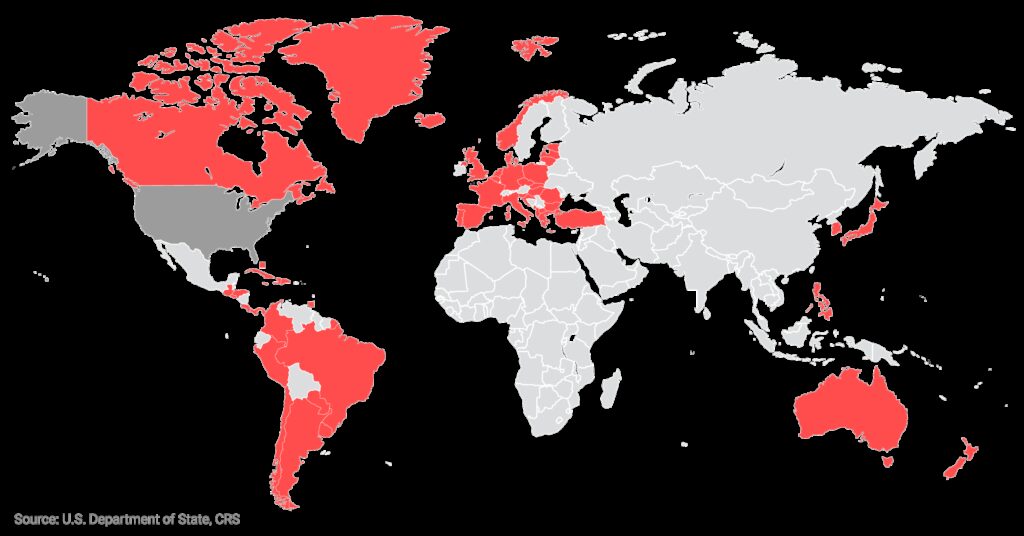

The United States has signed and ratified seven defense treaties that remain active today: the Rio Treaty (1947); NATO (1949); and bilateral defense commitments with Australia and New Zealand (ANZUS) (1951), the Philippines (1951), Korea (1953), and Japan (1960).2 Some of these commitments are more meaningful than others—the Rio Treaty has arguably become moribund—but all create real allies the United States is obligated on paper to defend: 51 countries and more than 1.4 billion people.3 To these, our definition would add nations the U.S. is now fighting alongside. But, with the U.S. exit from Afghanistan and anti-ISIS fighting essentially over in Iraq and Syria, this category of ally is now empty.

The term quasi-ally describes countries the United States is not committed to defend but that receive some degree of U.S. military and or political support such that the U.S. is clearly on its side against likely adversaries.4 This is intentionally not a precise definition; quasi-alliances are relevant because they are muddy affairs with blurry edges where leaders may wonder what exactly the U.S. will do for them in duress.

U.S. quasi-allies include the confusingly named “major non-NATO allies,” a legal status that “provides military and economic privileges,” but “does not entail any security commitments to the designated country.”5 Countries designated as MNNAs qualify for certain privileges: expedited approval for certain arms sales, eligibility for loans for joint research projects, authorization to house U.S. military stockpiles, eligibility to bid on contracts to service overseas U.S. forces, and more. Some MNNAs are treaty allies, but most are not: Bahrain, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Pakistan, Qatar, Taiwan, Thailand, and Tunisia.6

Taiwan is a quasi-ally by policy. Taiwan was once a true U.S. ally, but the United States has, since the normalization of relations with mainland China in 1979, followed a policy of “strategic ambiguity”—never committing to defend Taiwan, or committing not to, in order to avoid escalating tensions with China, while still deterring a prospective attack on Taiwan, and encouraging Taipei to not declare independence.7 The 1979 Taiwan Relations Act, largely a congressional response to the derecognition of Taiwan, commits the United States to provide “defense articles and defense services in such quantity as may be necessary to enable Taiwan to maintain a sufficient self-defense capability” but does not obligate the United States to defend Taiwan.8

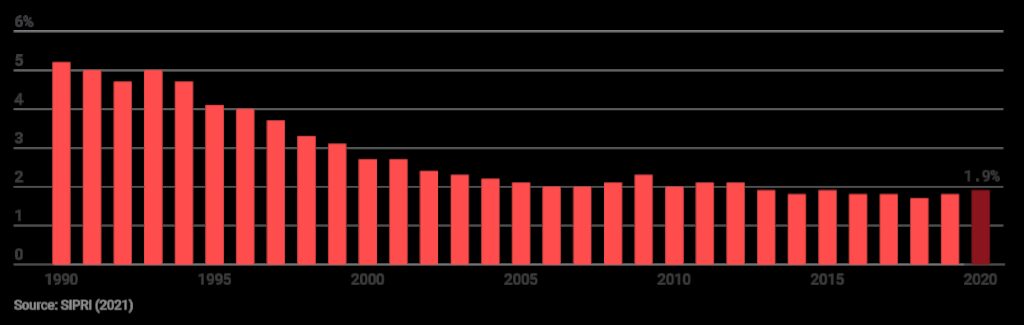

Taiwan’s military spending as a percentage of GDP

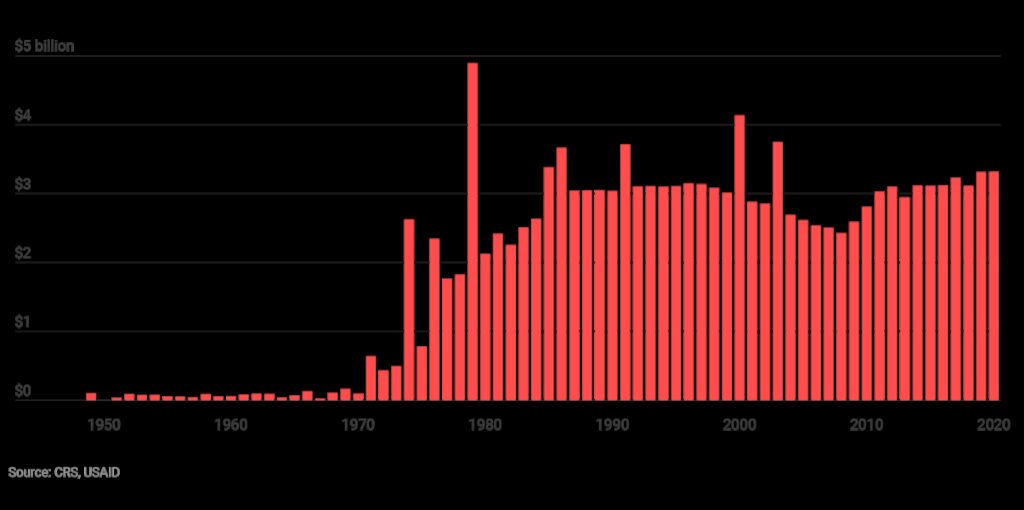

Israel is a quasi-ally, not an ally, as the U.S. has never formally committed to defend it.9 However, Israel is a unique quasi-ally, one closer to being an actual ally, in that the U.S. would likely defend it if it were attacked. U.S. policy support for Israel comes in the form of heavy aid (now more than $3 billion annually), including paying for the Iron-Dome missile defense system, and diplomatic backing, like voting against U.N. resolutions criticizing Israel.10 U.S. politicians also widely give Israel almost uniform rhetorical support, which is especially notable at times when it is broadly criticized elsewhere.11

U.S. bilateral aid to Israel

Saudi Arabia and other Arab Gulf States—Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Oman—are quasi-allies due to long-standing U.S. interest in the region’s oil production capacity, which has created a near consensus in Washington that U.S. support is needed to help these states deal with threats—once the Soviet Union, then Iraq, now Iran.12 Saudi Arabia’s key role in the global oil market and economic clout make it the most important of the Gulf quasi-allies. In recent years, Saudi Arabia has become a top destination for U.S.-made weapons and military equipment, with U.S. exports accounting for 79 percent of Saudi’s major conventional weapons between 2016 and 2020.13

In 1990, the United States came to Kuwait and Saudi Arabia’s aid following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait by deploying more than 500,000 U.S. troops to Saudi Arabia and then liberating Kuwait in the Gulf War.14 U.S. force levels in Saudi Arabia were reduced to the low hundreds in 2003, increased during the Trump administration, and now number 2,100.15

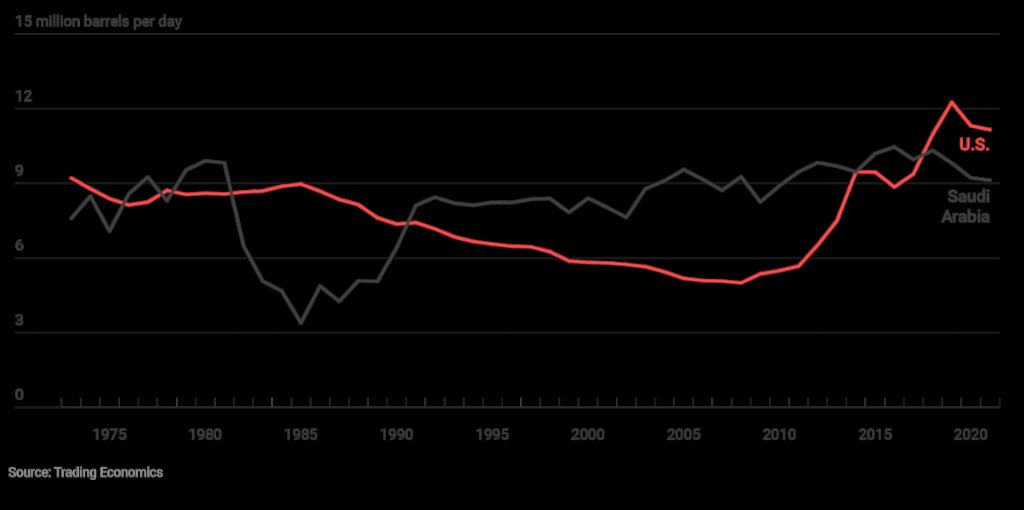

U.S. and Saudi Arabia oil production

Iraq is now also a quasi-ally, due to the ongoing U.S. troop presence there and stated mission to combat the Islamic State. When the Iraq war against ISIS was ongoing, Iraq, by our definition was an ally. But now, with ISIS’s territory lost and its fighters reduced to scattered bands, the U.S. is involved in a post-war stabilization mission, not a war. There are about 2,500 U.S. troops and no plans for their removal.16

As has become clear since Russia attacked it in February 2022, Ukraine is not a U.S. ally. Despite the heavy U.S. support that makes it a quasi-ally—over $60 billion in aid this year, intelligence support, and years of arms shipments and military training—the limit of the U.S. commitment is clear: no direct military involvement.17 As discussed below, this limit was sometimes deliberately obscured by top U.S. officials in their rhetoric and by the U.S. policies of holding open the prospect of Ukraine joining NATO and signing empty agreements, including vaguely signaling support for Ukraine’s sovereignty in November 2021.18

Quasi-allies entangle the U.S.

Quasi-allies are partly an outgrowth of the prevailing U.S. grand strategy of “primacy” or “liberal hegemony,” which guides U.S. foreign policy. The theory of primacy holds that the United States achieves security by maintaining military dominance everywhere, pacifying allies, and deterring all would-be challengers.19 If the United States balances or deters all global troublemakers, the thinking goes, others will not have to and the world will be saved from the consequences of anarchy—that is, from military competition, or at least its excesses. To primacy’s many advocates, allied states and U.S. garrisons stationed there are the chief means of exercising the military dominance needed to order global politics.

This mode of thinking—that the United States manages global politics through alliances and commitments of resolve to help various states—fuels the quasi-ally problem. Americans, especially the elites who dominate U.S. policymaking, see military commitments as an almost unvarnished good and promises that create expectations of U.S. support as inherently virtuous. So, the risks of implying that the U.S. will defend states it has no good reason to defend are ignored or dismissed.

An alliance entangles nations in each other’s security dynamics by design, theoretically in service of U.S. security interests.20 Quasi-allies entangle the United States less deliberately, in circumstances where U.S. interests are generally far murkier—if U.S. interests were obvious, an alliance commitment would likely follow. Essentially the nation confuses itself about its commitment and interest in defending these states. This occurs in two stages. First, with some set of official words and deeds, the United States links itself to another state’s defense—without, of course, formally agreeing to defend it and thus making it an ally. Subsequently, U.S. leaders see the fact that this occurred, that the state has achieved this quasi-ally status, as a rationale to do more for it, potentially even to fight a war for it. Cheap talk in this way can pave the way for expensive and risky commitments, if not actual uses of force.

These stages are important in understanding that entanglement with quasi-allies is not exactly an accident. There is likely both a deliberate effort by some elites to extend the U.S. security perimeter without a treaty and a secondary effect where others see quasi-ally status as binding in some sense. Hence causality is a bit complicated—the United States may both have quasi-allies because it set out to protect them and protect them because they are quasi-allies.

There are two ways this incidental side entanglement can occur: public confusion and leaders’ credibility fears. These mechanisms can operate in tandem. In both cases, U.S. leaders may feel trapped by prior policies and rhetoric, including their own.

Public confusion

The more quasi-allies are called allies or receive military aid or promises of vague support, the more the American public may consider it to be one. Special interest lobbies, like émigré groups, can amplify such misconceptions, resulting in democratic pressure to stand up for quasi-allies with military commitments. You would expect to see this most in Congress, the most democratic branch, with cries to stand up for “allies” like Israel or Taiwan, for example.21

Similarly, public opinion facilitated U.S. entry into the Korean War in 1950. On the heels of the communists “taking” China in 1949, the move was quite popular, with 78 percent of Americans approving of President Truman’s decision to send ground troops to Korea.22 Ukraine today is another example, with rhetoric insisting on continued U.S. support for Ukraine (as well as other, bigger factors, like public outrage against Russia) which increases congressional pressure to do more militarily for Ukraine.23

Misplaced fears about U.S. credibility

The other mechanism entangling the United States with quasi-allies is leaders’ belief that using the term “ally” puts U.S. credibility on the line. Due to largely misplaced beliefs about how credibility and deterrence work, U.S. leaders tend to think that once someone in power has said or implied that the U.S. will defend a state, not doing so becomes dangerous to actual allies. Leaders can also express these beliefs about credibility cynically, to win support for actions they support for other reasons. Either way, past hints at defending quasi-allies can become real defenses now, due to concerns about true allies.

There is little empirical or logical reason to believe credibility travels this way. The bulk of scholarship says it depends instead on local interests and capability. But some U.S. leaders seem to believe this theory and likely will act accordingly.24 Hence they may feel compelled to defend a quasi-ally that a country has no intrinsic interest in defending. A similar process might simply involve a misplaced sense of obligation; a vaguer sense that one must back your friends and allies for reputational or moral reasons.

The domino theory that fueled the U.S. involvement in Vietnam is an example of such credibility fears.25 Once the United States, through advisors and aid, became invested in South Vietnam’s success in suppressing communist insurgents, it took on quasi-ally status. U.S. leaders feared that its failure would endanger U.S. credibility to defend allies elsewhere and allow Communist gains.26

A more recent example is the Obama administration’s 2015 decision to back the Saudi Arabia-led campaign against the Houthis in Yemen with expedited arms sales and intelligence to help target airstrikes. Although the administration’s motivation remains somewhat unclear, former officials have pointed to a need to back the Saudis, as an ally of sorts, because of its position against Iran or its power in the oil market.27

Extending wars with shifting goals

Another form of entanglement with quasi-allies can occur during wars. Insistence that the United States is fighting for, rather than with, allies can confuse the means (allies) with the ends (winning the war) and prolong post-war occupations indefinitely. By the definition here, when a war ends but U.S. forces and other levers of support remain, a wartime ally becomes a quasi-ally. Having just fought a war in which they needed U.S. assistance, these quasi-allies tend to have major problems and want outside help to fix them. These problems easily get confused with U.S. security needs as the quasi-ally is wrongly still called an ally.

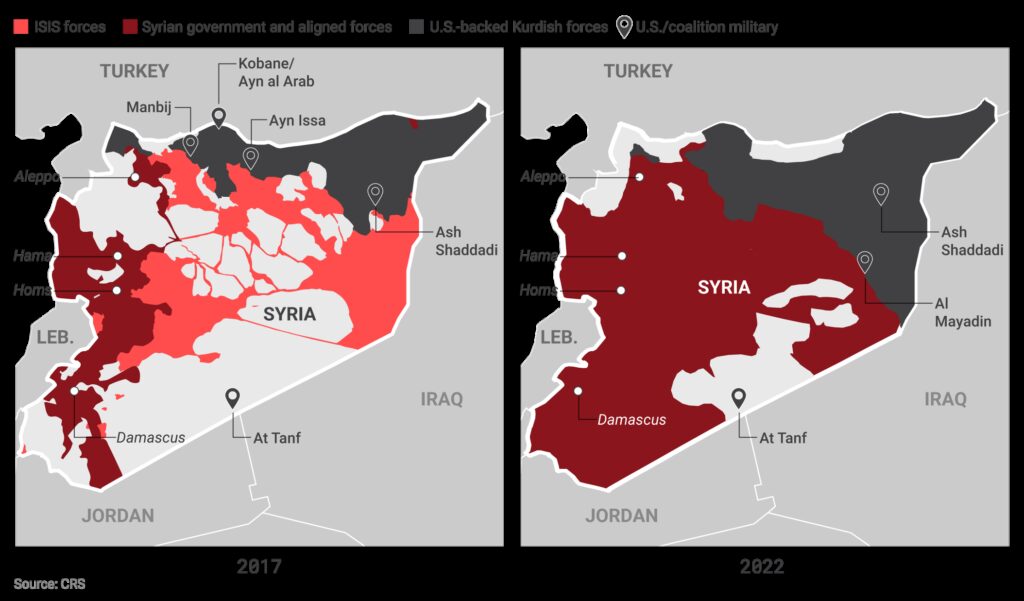

For example, per the definition used here, the Kurdish YPG (or People’s Protection Units) in Syria, which then formed the core of the Syrian Democratic Army, was a U.S. ally in the war against the Islamic State (ISIS).28 However, when U.S. anti-ISIS objectives were achieved, its territorial caliphate destroyed, it became common to assert the U.S. aim in Syria was now to protect its Kurdish ally.29 This shifted the focus of the U.S. mission and remains a rationale for keeping U.S. forces in Syria.30 A similar dynamic exists in Iraq, where U.S. military support for the Iraqi government lingers on in the name of defeating a largely extinct ISIS entity with no exit in sight.

The varied consequences of entanglement

The most dire consequence of entanglement with quasi-allies for the U.S. is getting dragged into a war in which it has no core interest in fighting. However, war is not the only risk. A misplaced sense of obligation to quasi-allies can also lead to wasted resources, like excessive U.S. basing and defense costs to defend quasi-allies; forgone opportunities to engage productively with quasi-allies’ rivals; and moral, or at least reputational, harm by being associated with quasi-allies’ misdeeds.

Map of the Syrian Civil War

U.S. policies in the Middle East exemplify these problems. Quasi-allyship with Gulf States, especially Saudi Arabia, has been a cause of the sprawling and costly basing infrastructure in the region.31 It has been a hurdle to diplomatic engagement with Iran, not only on the Iran deal but other matters like the war in Syria.32 It has also associated the United States with Saudi Arabian human rights abuses, starting with its escalatory and disproportionate bombing of civilians in Yemen.33 Likewise, even prior to Russia’s invasion in early 2022, U.S. support for Ukraine damaged relations with Russia, endangering useful cooperation on arms control, the war in Syria, and everything else—without actually protecting Ukraine.34

Quasi-allies generate moral hazard

The risks that limited U.S. commitments create for quasi-allies result from a kind of moral hazard. Moral hazard occurs when a party is more willing to run risk due to the expectation that someone else bears the cost.35 Because the United States is so militarily formidable, moral hazard is a major problem with U.S. allies, who may take provocative actions against adversaries due to confidence that the U.S. will back them up.36 In this way, U.S. defensive promises can encourage conflict between neighbors rather than discourage it. The twist with quasi-allies is that they run risks under the false idea that U.S. forces would protect them—in fact, they typically bear their own risk. Thus, they face more dire consequences than treaty allies (assuming the U.S. would honor its commitments to allies).37

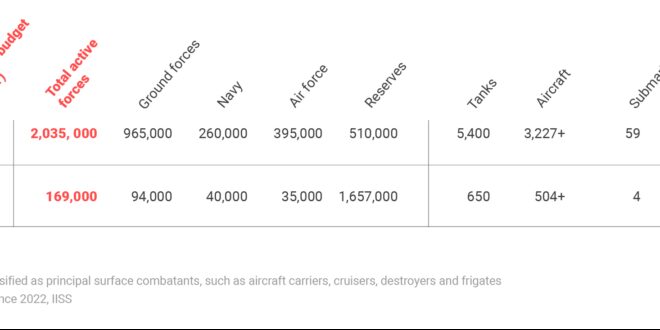

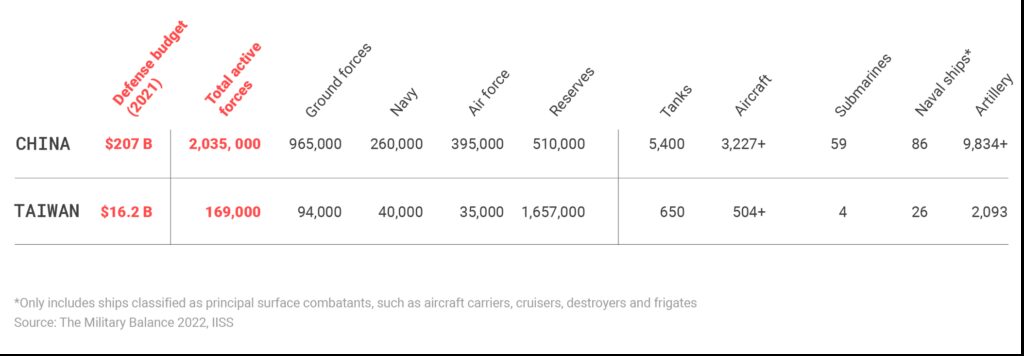

China and Taiwan military comparison

This sort of recklessness can involve taking insufficient measures for self-defense, under the expectation the U.S. threat makes doing more an unnecessary expense. Taiwan, a nation under great threat of invasion from China, spends around 2 percent of its gross domestic product on defense, much of it on big-ticket items of questionable utility to its primary security imperative of halting a Chinese amphibious invasion.38 One reason for this is Taipei wants to curry favor with U.S. policymakers in Washington; another, relatedly, is the prospect of U.S. military intervention undercuts the incentive for Taiwan to spend more or to spend more efficiently.39 The possibility of a more energetic defense effort could reduce potential U.S. support: a perverse incentive.

Moral hazard can entail provoking or even attacking a stronger adversary. Perceived U.S. support may drive states to take undue risks they otherwise would not. A major example is the Georgian Crisis of 2008. In April 2008, at the NATO Bucharest Summit, NATO allies committed to supporting Ukraine and Georgia’s eventual accession to NATO, as well as the “territorial integrity, independence, and sovereignty of Ukraine and Georgia.”40 That move and broadly supportive rhetoric in Washington likely gave Georgia false confidence when it sent troops into separatist South Ossetia later that year. Georgian leaders may not have believed that U.S. forces would back them with direct force but may have tragically thought that possibility would stay a Russian response. The move instead gave Russia pretext to invade, triggering the resulting five-day conflict that resulted in 850 Georgians killed and 35,000 displaced.41

More recently, Saudi Arabia may have overestimated the depths of U.S. support, encouraging risky behavior like its proxy war with the Iran-backed Houthi rebels in the Yemeni Civil War and other aggressive postures toward Iran and aligned actors in the region.42 Having received U.S. military support in Yemen during the Obama administration and strong rhetorical support from the Trump administration, Saudi leaders may have felt untouchable, especially by Iran.

However, in 2019, drones widely thought to be Iranian attacked targeted Saudi ARAMCO, the state-owned oil company, suspending its 5.7 million barrels per day of crude oil production.43 Even the Trump administration declined to retaliate on Saudi Arabia’s behalf—although a recent report claims President Trump himself wanted to.44 This may have been something of a wake-up call for Riyadh, a remedy for moral hazard, as the Kingdom subsequently entered diplomatic negotiations with Iran and talks to end its involvement in Yemen.45

Ukraine is the foremost example of the peril brought by the false prospect of U.S. support.46 As early as 1994, with the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances, U.S. leaders fostered the impression that they might be obligated to defend Ukraine. Although the agreement committed the United States (and other signatories) only to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty and complain to the U.N. Security Council if someone else did not, the agreement’s title seems designed to confuse people and imply Ukraine had something like a NATO Article 5 commitment; many U.S. commentators duly said so.47 In 2008, at the Bucharest Summit, the alliance, due to the efforts of the George W. Bush administration, supported Ukraine’s (and Georgia’s) eventual accession to NATO membership.48

However, NATO did not give Ukraine a date by which it would join, nor did it provide Ukraine with a Membership Action Plan, the standard way of putting countries on a path to joining. U.S. aid to Ukraine ratcheted up after Russia’s seizure of Crimea and support for rebels in eastern Ukraine in 2014, with only minor interruption due to President Trump’s suspension in efforts to gather dirt on his opponent Joe Biden’s son.49 In all other respects, the Trump administration continued or even enhanced U.S. support for Ukraine.50 Ukraine also became a NATO “Enhanced Opportunities Partner,” in 2020, which heightened its access to information sharing, interoperability programs, and exercises.51

As Russia began a buildup of troops along Ukraine’s border in early 2021, the Biden administration repeatedly emphasized its “unwavering” and “ironclad” support for Ukraine’s sovereignty.52 Coupled with an insistence that NATO retained an “open door” to Ukraine’s potential membership, this rhetoric may have fueled Ukraine’s hopes that the United States or NATO might intervene militarily on its behalf, although President Biden eventually ruled that out.53 It is hard to say that the prospect of U.S. and NATO support, however uncertain, caused Ukraine to avoid cutting a deal with Russia that would have avoided invasion. But it is fair to say that the U.S. support—its quasi-allyship—encouraged the uncompromising side of Ukrainian politics, which rejected Russian demands for their neutrality and swift implementation of the accords.54

Some might argue that quasi-allies like Ukraine know perfectly well that the United States has no real commitment to help them and should not be confused about the risks they bear. This is a reasonable rejoinder, but it misses the power of people and states in dire circumstances to generate false hope due to foreign powers. Ukraine, for example, in late 2021 would have had to make severe and perhaps humiliating sacrifices to avoid invasion by Russia: neutrality, acceptance of the loss of Crimea, and loss of control over much of Donbas—and even then it might not have staved off an attack.55

Nationalistic sentiment, fueled in part by Russia’s 2014 seizure of Crimea and support for rebels, and its political consequences made this sort of deal hard for any Ukrainian leader to swallow. The possibility of Western (especially U.S.) help, if only via deterrent threat, was a way to believe and act as though no such choice had to be made. It is easy to see how that could be appealing. U.S. military prowess has great power to heighten wishful thinking that already exists for good reasons.

Reduce the number of quasi-allies

Quasi-allies are not allies, but in some senses, U.S. leaders treat them as if they are. This ambiguity is dangerous. Confused audiences at home create pressure to treat them as real allies, as do overwrought concerns about U.S. credibility. Hinting by the United States coupled with wishful thinking abroad can fuel risky behavior in states that are overly confident in their American backing. Pretending to protect these states can encourage the fate the feint tried to avoid.

To those who might address the problem of ambiguity by forming more formal alliances, the issue is the United States already has many burdensome commitments disconnected from its vital interests. Also, as noted above, treaties do not extinguish doubt about U.S. commitments—they just make a stronger claim to having important interests at stake. Where U.S. interests are nonetheless unclear, U.S. intentions to fight for the ally are irrevocably unclear. So, the same problem of getting entangled in needless trouble would still occur, just more formally. And, to the extent the United States would not actually follow through on its alliance commitments where its interests are murky—say to Montenegro, Lithuania, or El Salvador—allies would risk even worse moral hazard problems. Having been formally told that they have U.S. military backing, countries such as these would be even more prone to over-rely on it.

Clarity by subtraction, not addition, of such half-baked commitments is the solution. This would require not only greater rhetorical discipline from presidents and their aides (Congress being largely a lost cause), but also fewer international agreements meant to give a sense of commitment. Also, blunt reminders to larger recipients of U.S. arms sales that support is not equal to a security commitment would be useful.

Making it clear that quasi-allies are not allies will limit the U.S tendency to entangle itself in places in which it lacks a real interest. While the United States cannot eliminate wishful thinking among its security dependents, such a clarification would make them more likely to accurately assess the balance of power with their adversaries, recognizing what it is rather than what they wish it to be, with imagined U.S. support providing these clients a false sense of security.

Arresting the tendency to confuse who is an ally will help limit these problems but will not halt them. The deeper issue is the belief that U.S. security comes from an endless array of allies, quasi-allies, and vague promises to defend so much of the world. It is intimately related to the tendency to see a solution involving the U.S. military for global security problems. Fixing that is a tall order. Discipline about who the United States is planning to defend is a useful first step.

Endnotes

1 Meriam-Webster defines an ally as: “(1) a sovereign or state associated with another by treaty or league and (2) one that is associated with another as a helper: a person or group that provides assistance and support in an ongoing effort, activity, or struggle.” “Ally,” Merriam-Webster, accessed March 31, 2022, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ally. The first of these definitions is appropriate for international relations; the second is for other matters. To this first definition, we add wartime partners, even if not bound by treaty, as any definition not including them would violate almost everyone’s idea of what an ally is. This second kind of alliance ends when the war, or one state’s participation in it, ends. Some formal definitions of alliance, to be sure, include informal arrangements. For example, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics and International Relations defines an ally as “An informal or formal relationship between groups, parties, peoples, states, or organizations for common purpose and mutual strategic and political benefits.” Others, however, agree with our emphasis on formality. The Max Planck Encyclopedia of International Law, for example, says: “An alliance is a formal union or league between States designed to achieve a common objective through combined action.” “Alliances,” Max Planck Encyclopedias of International Law, https://opil.ouplaw.com/view/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e896#:~:text=1%20An%20alliance%20is%20a,common%20objective%20through%20combined%20action.

2 “Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance,” Department of International Law, OAS, September 2, 1947, http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/treaties/b-29.html; “The North Atlantic Treaty,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, April 4, 1949, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_17120.html; “Security Treaty Between the United States, Australia, and New Zealand (ANZUS),” Avalon Project Yale Law School, September 1, 1951, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/usmu002.asp; “Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines,” Avalon Project Yale Law School, August 30, 1951, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/phil001.asp; “Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea,” Avalon Project Yale Law School, October 1, 1953, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/kor001.asp; “Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty (Manila Pact),” Avalon Project Yale Law School, September 8, 1954, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/usmu003.asp; “Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States of America and Japan,” Asia for Educators, Columbia University, January 19, 1960, http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/japan/mutual_cooperation_treaty.pdf.

3 Venezuela is not counted as party to the Rio Treaty, despite Juan Guaido’s opposition government reentering the treaty in 2019, due to the ongoing presidential crisis and unclear legitimacy. This count also does not include members of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, as this treaty has been defunct for decades. Further, due to the United States’ defense commitment to France, French Guinea is also included in the map of U.S. allies; however, in the number of countries, they are both counted as one.

4 A related term is “client state,” which is a state that depends on another. But this does not capture what we are discussing here because a client state could be an ally.

5 “Major Non-NATO Ally Status,” U.S. Department of Defense Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, January 20, 2021, https://www.state.gov/major-non-nato-ally-status/.

6 The State Department recognizes 17 countries as MNNAs: the countries listed above, as well as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, and the Philippines, who are treaty allies, but outside of NATO. These countries are allies, as opposed to the MNNAs with whom the United States does not have a defense treaty. Public Law 107-228 (2002) stated that Taiwan would be treated as an MNNA, without formal designation. C. Todd Lopez, “‘Major Non-NATO Ally’ Designation Will Enhance U.S. Qatar Relationship,” U.S. Department of Defense, January 31, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2917336/major-non-nato-ally-designation-will-enhance-us-qatar-relationship/.

7 “Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of China,” Avalon Project Yale Law School, December 2, 1954, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/chin001.asp; “Taiwan Relations Act,” American Institute in Taiwan, January 1, 1979, https://www.ait.org.tw/our-relationship/policy-history/key-u-s-foreign-policy-documents-region/taiwan-relations-act/; John Ruwitch, “A Stronger China Tests America’s ‘Strategic Ambiguity’ on Taiwan,” NPR, November 30, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/11/30/1060185873/the-u-s-may-start-to-clarify-its-taiwan-policy.

8 “Taiwan Relations Act,” American Institute in Taiwan.

9 Some examples of the media and policymakers calling Israel an ally include: Alex Lockie, “Here’s Why the U.S. and Israel Are Such Close Allies,” Business Insider, February 18, 2017, https://www.businessinsider.com/us-israel-allies-2017-2; Tom Cole, “Israel’s Longest and Most Loyal Ally,” Congressman Tom Cole Media Center: Weekly Columns, May 24, 2021, https://cole.house.gov/media-center/weekly-columns/israels-longest-and-most-loyal-ally; Brian Mast, “Supporting our Ally Israel,” Congressman Brian Mast, https://mast.house.gov/israel?page=2.

10 The U.S. military aid program to Israel was instituted after the Six-Day War of 1967 and vastly increased after the Camp David Accords in 1978, resulting in a peace deal between Egypt and Israel and heavy annual U.S. aid to both nations. Israel now receives more than $3 billion annually in aid. Jeremy Sharp, “U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel,” Congressional Research Service, February 18, 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/mideast/RL33222.pdf.

11 For example, in a speech in May 2008, President George W. Bush said, “The alliance between [the United States and Israel] is unbreakable, yet the source of our friendship runs deeper than any treaty.” “President Bush Addresses Members of the Knesset,” White House, May 15, 2008, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2008/05/20080515-1.html. President Barack Obama echoed the sentiment in 2019, calling America’s commitment to Israel “unshakeable” and, in 2021, U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III described America’s partnership with Israel as “ironclad.” “Remarks by President Obama in Address to the United Nations General Assembly,” White House, September 21, 2011, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/09/21/remarks-president-obama-address-united-nations-general-assembly; Jim Garamone, “Austin Says U.S. Commitment to Israel Remains ‘Ironclad,’” Department of Defense News, April 11, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2568144/austin-says-us-commitment-to-israel-remains-ironclad/.

12 Today, Saudi Arabia is by far the largest OPEC exporter and the source of 7 percent of U.S. total petroleum imports and 8 percent of U.S. crude oil imports. Some examples of Saudi Arabia being falsely labeled an ally include: Jeffrey Fields, “Why Repressive Saudi Arabia Remains a U.S. Ally,” The Conversation, March 3, 2021, https://theconversation.com/why-repressive-saudi-arabia-remains-a-us-ally-156281; “U.S.-Saudi Arabia Relations,” Council on Foreign Relations, December 7, 2018, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-saudi-arabia-relations; Keith Johnson and Robbie Gramer, “How the Bottom Fell Out of the U.S.-Saudi Alliance,” Foreign Policy, April 23, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/23/saudi-arabia-trump-congress-breaking-point-relationship-oil-geopolitics/. Zack Beauchamp, “Beyond Oil: the U.S.-Saudi Alliance, Explained,” Vox, January 6, 2016, https://www.vox.com/2016/1/6/10719728/us-saudi-arabia-allies.

13 Saudi Arabia accounted for 24 percent of all U.S. arms sales during that same time period with nearly $37 billion worth of arms purchases, the largest single destination for U.S. arms. “U.S. Arms Exports,” Campaign Against Arms Trade, June 3, 2021, https://caat.org.uk/data/countries/united-states/us-arms-exports/.

14 Alan Taylor, “Operation Desert Storm: 25 Years Since the First Gulf War,” Atlantic, January 14, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2016/01/operation-desert-storm-25-years-since-the-first-gulf-war/424191/.

15 Eric Schmitt, “Aftereffects: The Pullout; U.S. to Withdraw All Combat Units from Saudi Arabia,” New York Times, April 30, 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/04/30/world/aftereffects-the-pullout-us-to-withdraw-all-combat-units-from-saudi-arabia.html; Eric Schmitt and David Sanger, “Trump Orders Troops and Weapons to Saudi Arabia in Message of Deterrence to Iran,” New York Times, October 11, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/11/world/middleeast/trump-saudi-arabia-iran-troops.html; John Vandiver, “U.S. Continues Building Troop Presence in Saudi Arabia,” Stars and Stripes, November 20, 2019, https://www.stripes.com/theaters/middle_east/us-continues-building-troop-presence-in-saudi-arabia-1.607950; “Letter to the Speaker of the House and President Pro Tempore of the Senate Regarding the War Powers Report,” White House, December 7, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/12/07/letter-to-the-speaker-of-the-house-and-president-pro-tempore-of-the-senate-regarding-the-war-powers-report-2/.

16 Meaghan Myers, “U.S. Troops Will Likely be in Iraq for Years to Come, Central Command Boss Says, Military Times, March 18, 2022, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2022/03/18/us-troops-will-likely-be-in-iraq-for-years-to-come-central-command-boss-says/.

17 Media, throughout the recent Russia-Ukraine crisis and war, have repeatedly and wrongly referred to Ukraine as a U.S. ally. Some examples include: Jonathan Weisman, “Republican Rift on Ukraine Could Undercut U.S. Appeals to Allies,” New York Times, January 26, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/26/us/politics/republicans-ukraine.html; Michael Crowley and David Sanger, “U.S. and NATO Respond to Putin’s Demands as Ukraine Tensions Mount,” New York Times, January 26, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/26/us/politics/russia-demands-us-ukraine.html.

18 “U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership,” U.S. Department of State, November 10, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-ukraine-charter-on-strategic-partnership/.

19 On primacy’s politics and why it is so popular among elites, see Benjamin H. Friedman and Harvey M. Sapolsky, “Unrestrained: The Politics of America’s Primacist Foreign Policy,” in A. Trevor Thrall and Benjamin H. Friedman, eds., U.S. Grand Strategy in the 21st Century: The Case for Restraint (New York: Routledge, 2018).

20 On the definition of entanglement and its relationship with entrapment, see Michael Beckley, “The Myth of Entangling Alliances: Reassessing the Security Risks of U.S. Defense Pacts,” International Security 39, no. 4 (Spring 2015): 7–48; Jennifer Lind, “Article Review 52 on ‘The Myth of Entangling Alliances,’” International Security Studies Forum, April 2016, https://issforum.org/articlereviews/52-entangling-alliances#_ftn9.

21 “Menendez, Rubio, Curtis, Pappas Introduce Legislation to Rename Taiwan’s De Facto Diplomatic Outpost,” United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, February 4, 2022, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/press/chair/release/menendez-rubio-curtis-pappas-introduce-legislation-to-rename-taiwans-de-facto-diplomatic-outpost.

22 While Dean Acheson famously defined South Korea as outside the U.S. defense perimeter, it was a quasi-ally due to U.S. aid and occupational forces there after World War II. Dean Acheson, “Remarks by Dean Acheson Before the National Press Club,” Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, January 12, 1950, https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/research-files/remarks-dean-acheson-national-press-club; Steve Crabtree, “The Gallup Brain: Americans and the Korean War,” Gallup, February 4, 2003, https://news.gallup.com/poll/7741/gallup-brain-americans-korean-war.aspx.

23 Jonathan Weisman, “Ukraine War Shifts the Agenda in Congress, Empowering the Center,” New York Times, March 15, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/15/us/politics/ukraine-politics-congress.html.

24 Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007).

25 Heather Stur, “Why the United States Went to War in Vietnam,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 28, 2017, https://www.fpri.org/article/2017/04/united-states-went-war-vietnam/.

26 To a large extent, domino theories are probably more of a justification for actions policymakers already prefer than their real rationale, but presumably these theories convince some people, there are true believers, so the theories are casually relevant, a cause of war. Jack Snyder, Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013), 276–300.

27 James Reinl, “Obama Aide: How We Got it Wrong in Yemen,” TRT World, February 14, 2019, https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/obama-aide-how-we-got-it-wrong-in-yemen-24162; Jeffrey Fields, “Why Repressive Saudi Arabia Remains a U.S. Ally,” Conversation, March 3, 2021, https://theconversation.com/why-repressive-saudi-arabia-remains-a-us-ally-156281; Iain Marlow, “Why U.S. Sees Saudi Arabia Again as Partner, Not Pariah,” Bloomberg, July 11, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-11/why-us-sees-saudi-arabia-again-as-partner-not-pariah-quicktake#xj4y7vzkg.

28 An example among many of Kurdish forces being called allies is Cora Engelbrecht, “The U.S.-Kurd Alliance in Syria Has a Tangled History,” New York Times, January 26, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/26/world/middleeast/us-kurds-syria.html.

29 Liz Sly, Sarah Dadouch, and Asser Khattab, “Syrian Kurds see American Betrayal and Warn Fight against ISIS is Now in Doubt,” Washington Post, October 7, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/syrian-kurds-see-american-betrayal-and-warn-alliance-against-isis-is-now-in-doubt/2019/10/07/96c425da-e902-11e9-a329-7378fbfa1b63_story.html. Some examples of the SDF or YPG being referred to as allies include: Ari Shapiro and Bilal Wahab, “A Look at the History of the U.S. Alliance with the Kurds,” NPR, October 10, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/10/10/769044811/a-look-at-the-history-of-the-u-s-alliance-with-the-kurds?t=1656084834164; Louisa Loveluck, “As U.S. Completes Afghan Withdrawal, American Allies in Syria Watch Warily,” Washington Post, August 31, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/syria-sdf-kurds-mazloum-kobane/2021/08/30/029d1cd8-ff79-11eb-825d-01701f9ded64_story.html.

30 Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Disentangling from Syria’s Civil War: The Case for U.S. Military Withdrawal,” Defense Priorities, May 29, 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/disentangling-from-syrias-civil-war.

31 Benjamin Denison, “Bases, Logistics, and the Problem of Temptation in the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, May 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/bases-logistics-and-the-problem-of-temptation-in-the-middle-east.

32 “Assad-ally Iran wants Saudi Arabia excluded from Syria talks,” New Arab, December 29, 2016, https://english.alaraby.co.uk/news/assad-ally-iran-wants-saudi-arabia-excluded-syria-talks?amp=1; Zaina Fattah, Ben Bartenstein, and Daniel Avis, “UAE, Israel Pressure U.S. for Iran Security Guarantees,” Bloomberg, March 14, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-14/uae-israel-pressure-u-s-for-iran-security-guarantees; Ashish Kumar Sen, “Strange Bedfellows: Saudi Arabia, Israel Oppose Iran Nuclear Deal for Different Reasons,” New Atlanticist, March 16, 2015, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/strange-bedfellows-saudi-arabia-israel-oppose-iran-nuclear-deal-for-different-reasons/.

33 Andrea Prasow, “U.S. War Crimes in Yemen: Stop Looking the Other Way,” Human Rights Watch, September 21, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/21/us-war-crimes-yemen-stop-looking-other-way.

34 On damage to arms control, see, for example, “U.S.-Russia Nuclear Weapons Inspections Must Resume before New Arms Talks, Says U.S.,” Reuters, September 2, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/us-russia-nuclear-weapons-inspections-must-resume-before-new-arms-talks-says-us-2022-09-01/.

35 “Definition of ‘Moral Hazard,’” Economic Times, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/definition/moral-hazard.

36 On allied moral hazard or “reckless driving,” see Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014), 65–67. See also Alan J. Kuperman, “Mitigating the Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention: Lessons from Economics,” Global Governance 14, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 219–224.

37 There remains a degree of ambiguity in all U.S. defense commitments, formal and informal, so the problem is not strictly limited to quasi-allies. On the inherent uncertainly of commitments to fight for others, see Joshua Rovner, “Ambiguity is a Fact, Not a Policy,” War on the Rocks, July 22, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/07/ambiguity-is-a-fact-not-a-policy/.

38 On Taiwan’s low spending, see Doug Bandow, “Why is Taiwan Only Spending 2.1 Percent of Its GDP on Its Defense?” Responsible Statecraft, October 26, 2021, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/10/26/how-the-us-can-compel-allies-to-spend-more-for-their-own-defense/. On its misallocation, see Michael A. Hunzeker, “Taiwan’s Defense Plans Are Going Off the Rails,” War on the Rocks, November 18, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/11/taiwans-defense-plans-are-going-off-the-rails/.

39 Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (Winter 2019): 171–189, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103.

40 “Press Release: Bucharest Summit Declaration,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, April 3, 2008, updated July 5, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_8443.htm.

41 Michael Kofman, “The August War, Ten Years On: A Retrospective on the Russo-Georgian War,” War on the Rocks, August 17, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/08/the-august-war-ten-years-on-a-retrospective-on-the-russo-georgian-war/; Sarah Pruitt, “How a Five-Day War with Georgia Allowed Russia to Reassert Its Military Might,” History, August 8, 2019, updated September 4, 2018, https://www.history.com/news/russia-georgia-war-military-nato.

42 On these dynamics, see Aaron David Miller and Richard Sokolsky, “Donald Trump Has Unleashed the Saudi Arabia We Always Wanted — and Feared,” Foreign Policy, November 10, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/11/10/donald-trump-has-unleashed-the-saudi-arabia-we-always-wanted-and-feared/.

43 David Reid, “Saudi Aramco reveals attack damage at oil production plants,” CNBC, September 20, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/20/oil-drone-attack-damage-revealed-at-saudi-aramco-facility.html; Ben Hubbard, Palko Karasz, and Stanley Reed, “Two Major Saudi Oil Installations Hit by Drone Strike, and U.S. Blames Iran,” New York Times, September 14, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/14/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-refineries-drone-attack.html. The attack on Saudi Aramco was claimed by the Yemeni Houthi group, one of Iran’s proxy forces.

44 Stephen Kalin, Summer Said, and David S. Cloud, “How U.S. Saudi Relations Reached the Breaking Point,” Wall Street Journal, April 19, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-u-s-saudi-relations-reached-the-breaking-point-11650383578?mod=e2tw.

45 Hussein Ibish, “Will Saudi Arabia and Iran Make Peace Over Yemen?” Washington Post, October 15, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/will-saudi-arabia-and-iran-make-peaceover-yemen/2021/10/14/c5b3f72e-2cb4-11ec-b17d-985c186de338_story.html.

46 Benjamin H. Friedman, “Biden Doesn’t Like Russia’s Meddling in Ukraine. But He’s Not Prepared to Stop It,” NBC News, May 6, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/biden-doesn-t-russia-s-meddling-ukraine-he-s-not-ncna1266535; Natalie Armbruster, “Did America’s ‘Good Intentions’ in Ukraine Make the Crisis Worse?” 19FortyFive, March 4, 2022, https://www.19fortyfive.com/2022/03/did-americas-good-intentions-in-ukraine-make-the-crisis-worse.

47 Katya Soldak, “Ukraine: How A U.S. Ally Is Being Made a Scapegoat,” Forbes, December 23, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesinternational/2019/12/23/ukraine-how-a-us-ally-is-being-made-a-scapegoat/?sh=4c9b9b8a594d.

48 “Press Release: Bucharest Summit Declaration,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

49 W.J. Hennigan, “Obama Approves $75 Million in Nonlethal Aid to Ukraine,” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2015, https://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-us-ukraine-aid-20150311-story.html.

50 Karen DeYoung, “The U.S. has been rushing to arm Ukraine, but for years it stalled on providing weapons,” Washington Post, February 27, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/02/27/ukraine-us-arms-supply/.

51 “NATO Grants Ukraine ‘Enhanced Opportunities Partner’ Status,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, June 12, 2020, https://www.rferl.org/a/nato-grants-ukraine-enhanced-opportunities-partner-status/30667898.html. Other NATO Enhanced Opportunities Partners are Australia, Finland, Georgia, Jordan, and Sweden.

52 Michael Crowley, “Blinken Will Visit Ukraine in Show of Support Against Russia,” New York Times, April 30, 2021, updated November 11, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/30/us/politics/blinken-biden-ukraine-russia.html; “Ukraine’s Yermak Assured of “Ironclad” U.S. Support in Call With Sullivan—Tweet,” Reuters, November 26, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraines-yermak-assured-ironclad-us-support-call-with-sullivan-tweet-2021-11-26/; Jim Garamone, “Defense Secretary Says U.S. Commitment to NATO Defense ‘Ironclad,’ Department of Defense News, February 17, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2938530/defense-secretary-says-us-commitment-to-nato-defense-ironclad/.

53 John Wagner and Ashley Parker, “Biden Say U.S. Troops ‘Not on the Table’ for Ukraine,” Washington Post, December 8, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/biden-says-ground-troops-not-on-the-table-but-putin-would-face-severe-economic-sanctions-for-ukraine-invasion/2021/12/08/3b975d46-5843-11ec-9a18-a506cf3aa31d_story.html.

54 Stephen Bryen, “War Looms as U.S. and Kiev Ignore Minsk II Protocols,” Asia Times, February 21, 2022, https://asiatimes.com/2022/02/war-looms-as-us-and-kiev-ignore-minsk-ii-protocols.

55 Stephen Van Evera, “To Prevent War and Secure Ukraine, Make Ukraine Neutral,” Defense Priorities, February 19, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/to-prevent-war-and-secure-ukraine-make-ukraine-neutral.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News