Dr. Stephen Blank, a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s Eurasia Program, in his piece entitled “Is Kazakhstan Russia’s Next Target?” and published by Real Clear Defense, raises the question in the following way: “Is Kazakhstan, rather than another European state, Russia’s next target?”. Further, he explains what he in particular means as follows: “This is not an idle or frivolous question, quite the contrary. Admittedly many NATO members and NATO’s senior leaders have recently warned that Russia has designs on their territory and within 3-8 years (depending on the speaker) might attack them. Those warnings are certainly well founded. Nevertheless, and although the European situation is certainly alarming and a rightful U.S. priority; we cannot, however, exclude alternative threats from Russia to other neighbors.

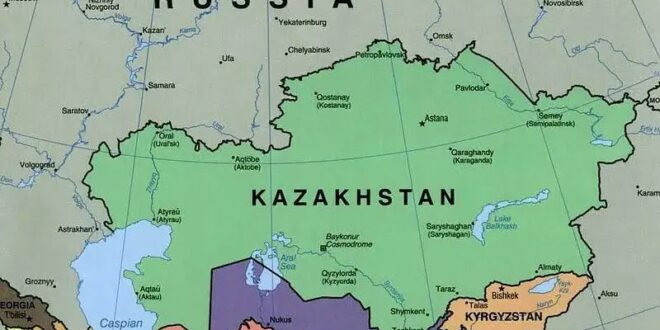

Indeed, in the last year the most consistent barrage of Russian threats has targeted Kazakhstan in Central Asia as a possible candidate for Moscow’s territorial aggrandizement and invasion. Presumably such threats are directed at least at Kazakhstan’s northern territory that adjoins the Russian Federation and which many Russian nationalists, not least Aleksandr’ Solzhenitsyn, claim should be or is actually part of Russia proper”.

The position, from which Stephen Blank here speaks, appears to be not only interesting, but also illustrative for understanding where the Western expert community exactly is in terms of grasping the way relations between Russia and Kazakhstan now are being unfolded. He says: “When we remember that the long-standing Tsarist justification of invasions of neighbors dating back to Peter the Great is Russia’s self-ordained role as protector of Orthodox Christians and now, in Ukraine, of Russians, these threats must be seen as laying the groundwork for a Casus Belli (cause of war) against Kazakhstan. Moreover, this threat is now regularly reinforced on a weekly basis by prominent members of the Russian media”.

Merely to pose this threat, according to him, “raises a host of questions that have not even been considered let alone answered”. He then lists those questions: “For example, why would Russia, especially with the lessons of Ukraine in mind consider such an adventuresome if not adventurist option? Second, what does it hope to gain thereby? Third, how would it strike at Kazakhstan and with what objectives in mind? Fourth, would Kazakhstan adopt policies that would increase the risk to itself given what it already knows about Russia’s imperialist proclivities? And, if so and fifth, why would it do so? Furthermore, how would Kazakhstan either prepare for this war or defend itself?”.

“Obviously, nobody has even pondered these issues in print. But it is also all too likely that too few foreign analysts have even remotely considered this issue”, Stephen Blank notes. He next refers to the inadmissibility not only for Kazakhstan but also for foreign governments (including those who are seriously involved with the Central Asian country in one or another form) of “the luxury of ignoring this potential scenario and others that may derive from or be linked to it”.

Two more important questions, raised by Stephen Blank, are: How both Washington and/or NATO would react, and not only in the military domain, to any threat to Kazakhstan let alone a genuine act of war?; If China would oppose a Russian invasion of Kazakhstan, how Chinese opposition might manifest itself?

This author as one who sees matters in hand from the Kazakhstani perspective would like to express his point of view on the topic and some questions raised by Stephen Blank in his piece.

Here’s what is to be said first in this regard. Yes, Ukraine and Kazakhstan are indeed the two most important post-Soviet countries for Moscow. But the tendency to see Kazakhstan as a country that potentially may be directly attacked by Russia under the pretext of protecting the Russian minority in the country strictly in the way that was the case with Ukraine in 2022 seems rather inappropriate. And this is why. Ukraine is a European country, and the Ukrainians strive to become a full-fledged European nation by joining the European Union and NATO. Russia wants to impede Kyiv’s progress in Euro-Atlantic integrations. Outside the West, the current Russian-Ukrainian war launched by Putin is seen rather as a kind of intra-European war. Kazakhstan the population of which is made up of 80 percent non-Europeans, is a non-White nation. A deliberate Russian attack on that country, if this happens, will be seen in the so-called Global South (i.e. outside the West) as subjecting it to colonial aggression by a European power aimed at grabbing its most fertile lands (in Northern Kazakhstan) and its plentiful oil (in Western Kazakhstan). And this is not to mention the possibility that Russia’s outright annexation of Northern Kazakhstan, or any part of it, should this occur, would likely be seen by the Islamic world as an open incursion into the Kazakh territory, that is, as an aggression against their fellow Muslims, as a kind of the Orthodox Christian Reconquista or Crusade.

Yes, indeed, the adherents of the idea first publicly expressed by Alexander Solzhenitsyn are again and again demanding Russia take over Northern Kazakhstan. This did not start yesterday, of course, and most probably will not end tomorrow. As Casey Michel, an American investigative journalist, noted, in the early post-Soviet period, “there were four regions Moscow eyed for potential border revision. The first, Georgia’s Abkhazia region, Russia invaded in 2008. The second and third – Ukraine’s Crimea and Donbas regions – Russia invaded in 2014. The fourth is the only region Russia hasn’t yet seized: northern Kazakhstan”. Here, however, is an important point to note: the Kremlin decision-makers, who at one time supported the ‘Russian separatism’ in Transnistria (Moldova province partly populated by Russians), and in Crimea and Donbas, as well as the ‘anti-Georgian’ separatism in the Southern Caucasus, did not even once express their readiness to afford to take real similar actions concerning Kazakhstan.

In the event of the repetition of the Russian experience with, say, Crimea and Donbas in Northern Kazakhstan, [the rest of] Kazakhstan, which the Russian leadership has been used to consider as the foothold they need to sustain the other four countries of the Central Asian region under its control, hardly will remain friendly and constructive concerning Moscow. This may, therefore, suggest that a Russian thrust through to Northern Kazakhstan and/or the Kazakh Altai (a part of Eastern Kazakhstan), should this happen, would cut off overland access from Russia to Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. In other words, the costs of pursuing that path may far outweigh the gains.

But that hardly has to mean that Moscow is not inclined to do with Kazakhstan what it did with Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova. Here the matter seems to be different. As Vladimir Pozner, a French-born Russian-American journalist and presenter, said a short while ago, ‘President Vladimir Putin is anything, but crazy’. And the Kremlin master’s endgame concerning Kazakhstan seems to lie in his intention to capitalize on the specifics of the traditional Kazakh society and to create between the groups of which it is composed such dividing lines as the ones that, say, arose between Georgians and Abkhazians in late Soviet and post-Soviet Georgia, and are arising between Moldovans and Gagauzians in nowadays Moldova.

The true nature of the relationship between policy and decision makers belonging to three different traditional tribal groups – the Senior, Middle and Junior zhuzes – is a side of Kazakh society that is incomprehensible to outsiders, even to those who have long been living and working in Kazakhstan. But this is precisely the environment where Kazakh intra-elite relations are being formed. And it’s a very conservative environment. In close acquaintance with this environment, one comes to realize that little has changed there in the last 100 years. Testimony of this is what the Kazakh ex-Deputy-Prime Minister, Galym Abilsiitov, once said, ‘in Kazakhstan, the only form of the division [of society] that runs through force fields are the zhuzes; only on this basis – the fact of belonging to one or another zhuz – people identify each other’.

It may be assumed that there can be internal contradictions in the kind of society to which Galym Abilsiitov referred.

Here is how Wikipedia assesses the situation in question: At the top of the Olympus of State power, ‘representatives of the Middle [Northern, Central and Eastern Kazakhstan] and Junior [Western Kazakhstan] zhuzes, taken together, are much inferior in quantitative terms to those of the Senior zhuz [Southern Kazakhstan]’. This information might be somewhat out of date. And here is why. Since the January 2022 unrest, decisions have been and are being adopted to make the above kinds of imbalances become even more striking. Representatives from Southern Kazakhstan now hold four of the five highest State leadership positions. These are: Kassym-Jomart Tokayev (President), Maulen Ashimbayev (Chair of Parliament’s upper chamber), Olzhas Bektenov (Prime Minister) and Erlan Karin (State Secretary, State Counselor). The fifth, that of the Speaker of Parliament’s lower chamber, is now occupied by Yerlan Koshanov, a representative from Northern, Central and Eastern Kazakhstan (the Middle zhuz). For the first time since independence, Western Kazakhstan, which, due to its oil and gas industry, constitutes the cornerstone of the State’s economy and subsidizes all other regions of the country as the main donor, remains totally unrepresented in State leadership positions.

But some people claim that Erlan Karin, although he is a native of Southern Kazakhstan, is a member of the Junior zhuz. There is no documentary evidence for this, as that kind of information about a citizen is not subject to documentary fixation in Kazakhstan. In one of the interviews, Rakhat Aliyev, Nursultan Nazarbayev’s late former son-in-law, who had earlier been deputy chief of the KNB State security service (Kazakhstan’s successor to the Soviet KGB), said: “Dosym Satpayev once worked at the Central Asian Agency for Political Research, opened and funded by the National Security Committee [KNB]. It was headed by KNB agent Erlan Karin (archival materials, denunciations, and receipts are available). It is impossible to trust the opinion of “independent” experts both in the West and in Kazakhstan”.

Kassym-Jomart Tokayev came to power as Nursultan Nazarbayev’s appointee, who had allegedly been hand-picked as such because, apart from other reasons, of his coming from the Jalaiyr clan, which is considered to have the status of senior member in the Senior zhuz tribal union.

Moscow, having come to his aid in January 2022, not only helped him retain and consolidate his power, but also reinforced its own ‘king-making’ role in Kazakhstan so much that there now were persistent talks that the Kazakh regime ‘actually rests on the CSTO bayonets’. On the other hand, Russia, while reviewing its attitudes towards Northern Kazakhstan, is shifting increasingly from the model proposed by the writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in 1989, to the model put into effect by the Governor-General of Siberia Mikhail Speransky back in 1822. Recall that the first one proposed taking away Kazakhstan’s northern region, along with the Russians living there; the second offered abolishing the border between the Middle zhuz and Siberia as a political frontier and accept the so-called Siberian Kazakhs into Russian citizenship. Such a transformation means that the Russians are already casting the shadow of a ‘second Donbas’ over the northeast of Kazakhstan through provoking a split between the two main groups of Kazakhs – the Senior zhuz and the Middle zhuz. Here and here and here are just some evidences of that.

The above said can be supplemented by the following information. At the very end of last year, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed an executive order on granting Russian citizenship to citizens of the Republic of Belarus, the Republic of Kazakhstan, and the Republic of Moldova. It is meant to simplify the procedure for granting Russian citizenship to citizens of the Republic of Belarus, the Republic of Kazakhstan, and the Republic of Moldova. Then it was announced that Russia decided to open a general consulate in Aktau (the Mangystau province of Western Kazakhstan) – in addition to the four existing ones in Astana (Northern Kazakhstan), in Almaty (Southern Kazakhstan), in Oskemen (Eastern Kazakhstan), and in Oral (Western Kazakhstan). This will be the second Russian general consulate in Western Kazakhstan. This is even though the number of ethnic Russians in Western Kazakhstan is very much less than in the other three regions -Northern Kazakhstan, Southern Kazakhstan, and Eastern Kazakhstan. However, on the other hand, in the Mangystau province of Western Kazakhstan, the level of protest potential is, judging by the reports in the media, very high. And is it not an explanation of Russia’s decision to open a general consulate in Aktau?

What’s next? A rather direct has been State Duma deputy Mikhail Delyagin, when speaking on this matter: “Unless Northern Kazakhstan, along with Central and Western Kazakhstan, rejoins their Homeland [Russia] as a result of the upcoming events, it will be … well, like ditching Donbas [non-admission of the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic to Russia]”.

Anyway, Moscow’s plan for splitting up Kazakhstan is most probably already working, but very few people notice this.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News