Through a narrow opening no more than 50 centimeters wide, without any safety equipment, Hussein enters the heart of the primitive fuel refining stations (burners) every day, inhaling toxic gases and emitted chemical odors. He faces them with a scarf that does not protect him from severe bronchitis.Inside an iron tank, the young man is exposed to temperatures reaching around 50 degrees Celsius, with dense gases inside, all for about 35 USD in exchange for cleaning the burner, with two others earning the same wage.

Hussein has lived with his illness for two years due to exposure to the odors and gases in the burners of Tarhin village in eastern rural Aleppo, working daily to clean them despite knowing the risks that could cost him his life.

Hussein’s job is limited to cleaning and scraping solid residues inside the burner after refining oil, saying he forced himself to continue working for four years. He is aware of the negative effects on his health and body but wants to support his three children and meet their needs.

In addition to his illness, his children’s health has deteriorated due to the spread of harmful odors and smoke in the area’s skies and the proximity of their home to the burners. The children need medications to treat increasing skin infections caused by the harmful environment.

Hussein told Enab Baladi that his bronchitis forced him to leave the burners for four months, despite his desperate need for the job, as his health condition worsened. He went to the city of al-Bab for nearly daily treatment.

During his unemployment, financial burdens increased between hospital visits, medications, and household needs. The monthly cost of medical drugs is around 70 USD, forcing him to resume working at the oil burners, as he found no alternative.

Hussein’s case is one of hundreds in the village of Tarhin, crowded with primitive refineries, where people daily inhale toxic and carcinogenic gases.

From green cover to burners

From seven kilometers away, thick black smoke columns can be seen piercing the sky, with flames never extinguished underneath in Tarhin village, part of al-Bab city in eastern rural Aleppo.

Thick black smoke and toxic odors emanating from primitive fuel refining stations relentlessly and continuously pump toxins into the area’s air and soil. Crude oil waste has turned its red soil black over the past seven years.

Tarhin turned from a neglected small village in rural Aleppo to a major turning point for primitive burners operations in northern Syria, exporting fuel to the area.

A forest and green cover turned into barren land and a hotspot for gases, chemicals, and carcinogens, with 1200 primitive burners operating, pumping their toxins and waste, resulting in environmental disasters in the region’s air, land, and health of workers and residents, leaving devastating effects that will take years to recover from.

60% of Tarhin’s land turns into burners

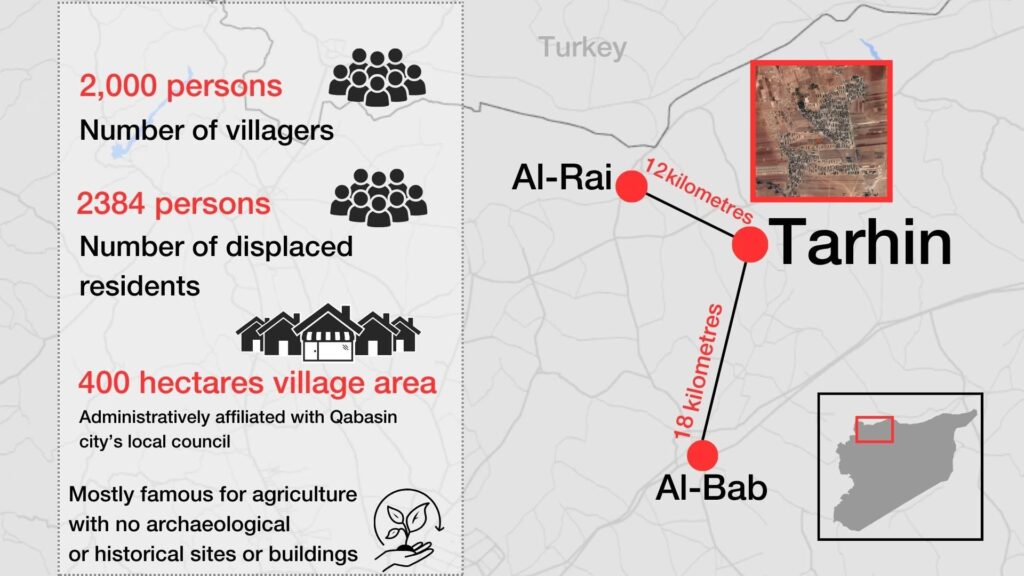

No statistics exist for the land area occupied by these burners. They are not limited to the now-barren forest but spread near roads and on the edges of some agricultural lands in Tarhin village.

Each burner occupies one dunum of land, plus about one dunum around it to ease burning and removing materials. By rough estimation, they occupy about 2400 dunums if calculating 1200 burners on two dunums each, approximately 240 hectares out of the village’s 400-hectare area.Barren land

Satellite images since 2011 show how the burners area gradually turned from agricultural lands, once planted with cypress and olive trees, into barren lands where hundreds of trees were cut, replaced by primitive burners.

During Enab Baladi‘s tour of Tarhin’s burners, the impact of their waste on the soil was evident. Oil spills blackened the land, along with piles of coal and waste from the burning process.

How do primitive oil burners work?

Enab Baladi toured Tarhin’s oil burners, meeting some burner owners and workers and tracking their operations from bringing in crude oil to selling its derivatives.

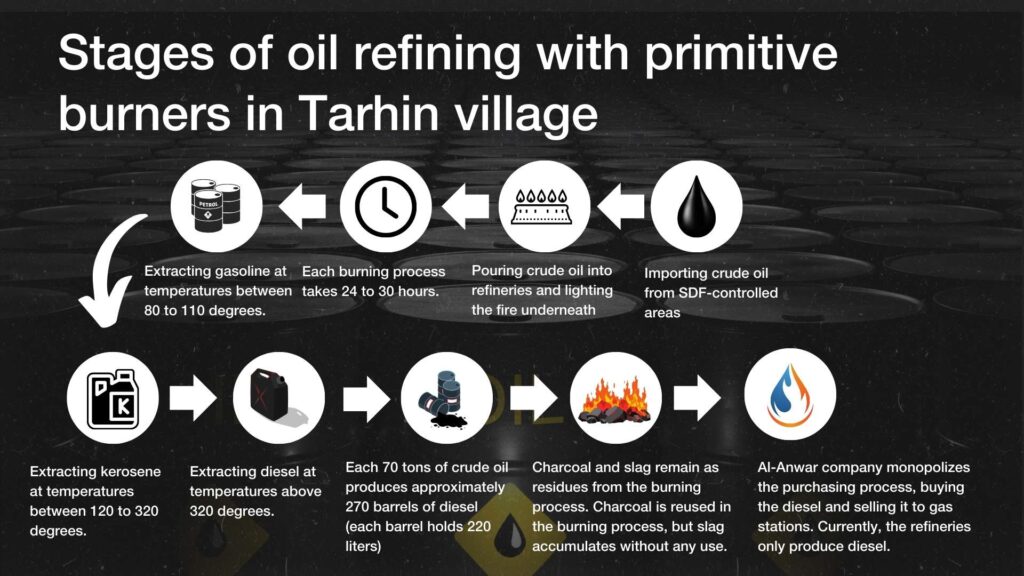

Primitive fuel refining stations (burners) spread in a forest near Tarhin, previously state-owned, with 1200 burners, each occupying about one dunum, relying primarily on crude oil. One ton of crude oil is placed in a metal tank, and fire is lit underneath to reach boiling point.

The price of one ton of crude oil ranges between 320 and 360 USD.

Crude oil vaporizes and passes through iron pipes surrounded by water to condense it into derivatives. Gasoline can be extracted at a temperature of 80 to 110 degrees, kerosene from 120 to 320 degrees, and above 320 degrees, diesel. Seventy tons of crude oil produce about 270 barrels, each barrel holding 220 liters, with the quantity increasing according to the burner size.

Burners do not produce gasoline and kerosene, as the controlling al-Anwar company only buys diesel, leading burner owners to produce only it.

Each burning process takes from 24 to 30 hours, involving four workers in two shifts, each earning 75 USD per each burning. Cleaning workers’ wages vary, needing three workers to collectively earn 100 USD.

After extracting derivative materials, coal and slag remain as burning waste. Ground coal is reused in burners or sold, while the slag has no value and is not used in any other process, accumulating in useless piles.

An economy shared by three factions

In the Tarhin area, the al-Anwar company, affiliated with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which has military control in Idlib, operates. HTS also has an arm in the area, Ahrar al-Sham (Ahrar Awlan), which helped the company impose its control over the owners of primitive refineries, and banned fuel traders from accessing the area to monopolize fuel trade. Hence, fuel sales can only be conducted through this company.

The company sets strict rules for purchasing the refineries’ products, buying only diesel, which is produced by the refineries in three types: the “Qarha” variety at $106.5 per barrel, the “Zahra” variety at $100 per barrel, and the “Asali” variety at $82 per barrel.

With 1200 primitive refineries operating, the region is divided into several sectors controlled by factions such as Ahrar al-Sham, Ahrar al-Sharqiya, and the Hamza Division (Hamzat). These factions impose tolls of $5 per ton of crude oil on refinery owners.

These tolls are financial fees collected by the company purchasing products from the refinery owners, who in turn collect these fees from the refinery operators.

Additional fees are imposed when transporting charcoal outside the region for sale, as part of the policy to control the trade of materials and direct it for the benefit of the controlling faction.

The price of one ton of charcoal ranges between $120 and $200.

The owners of primitive refineries view this as clear exploitation by the factions and the company, as they impose “excessive” fees without any clear legal or economic justification.

One trader and HTS as the biggest winner

Oil is a fundamental resource for the operation of the refineries. There is only one trader, Mahmoud Khalifa, who oversees purchasing oil from areas controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). He is the only one bringing crude oil into rural Aleppo, coordinating with SDF leaders.

Enab Baladi was unable to acquire more information about Mahmoud Khalifa, except that he belongs to the al-Jahishat tribe and manages oil purchase and sale operations through approximately 33 middlemen. Khalifa is affiliated with the Sultan Murad Division led by Faheem Issa.

According to sources, Khalifa takes advantage of security gaps to bring in oil through the internal al-Hamran crossing, relying on strong relationships with the responsible authorities in both rural Aleppo and within the SDF to facilitate his operations.

The price of one ton of crude oil ranges between $320 and $360.

Sources stated that the first beneficiary is HTS because it has its arm, Ahrar al-Sham – Eastern Sector, which handles some of the finances. Also, the al-Anwar company is affiliated with the HTS, representing a significant source of income for the HTS and its leader, Abu Mohammad al-Jolani.

Enab Baladi reached out to al-Anwar company for clarifications on accusations of monopolizing the purchase of fuel from primitive refineries in Tarhin, and the reason for imposing a $5 toll per ton of crude oil and restricting the purchase to diesel only from the refineries. However, no response was received by the time this report was published.

Enab Baladi also contacted the HTS for clarification about the company’s affiliation, but no response was received.

Money in al-Jolani’s treasury

After the defection of the third man in the HTS, Jihad Issa al-Sheikh, known as “Abu Ahmad Zakour,” from the faction, he revealed several issues and corruption files managed by Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, including oil monopolization and negotiation with the SDF to handle this file.

In January, Abu Ahmad Zakour said that al-Jolani held a negotiation meeting with those responsible for the fuel file within the SDF in Sarmada, northern Idlib. They discussed ways to monopolize fuel supplies and prevent commercial competition in the market, leading to an agreement on five points:

Canceling previous contracts with suppliers who previously imported fuel.

Establishing al-Anwar company managed by Abu Mohammad Madarat and Abu Abdullah Watad, with exclusive fuel distribution rights.

Assigning the al-Shahba Gathering (a military formation in rural Aleppo that later dissolved itself) to collect tolls from traders moving fuel from Jarablus toward al-Bab, Azaz, and Afrin, as a financial source taken directly from traders.

Ensuring fuel arrives in Idlib at cheaper prices than in rural Aleppo to showcase better living conditions under their control compared to areas controlled by the Syrian National Army.

Reducing the amounts of fuel distributed to bakeries in northern and eastern rural Aleppo to force them to buy from traders selling at higher prices, leading to higher bread prices and increased civilian hardship.Zakour mentioned that al-Shahba Gathering benefits from the fuel trade by over $500,000, considering it a support from al-Jolani to use these funds for bribery and creating chaos in northern Syria.

He added that al-Jolani profits more than $10 million from the fuel contract, which he uses to open malls and businesses to collect the region’s money into his own treasury.

Zakour did not specify the time frame for accumulating these financial returns, and Enab Baladi could not correlate the provided information with an independent source.

Stages of oil refining with primitive burners in Tarhin village

Step 1: Importing crude oil from SDF-controlled areas.

The price per ton ranges between $320 and $360.

Step 2: Pouring crude oil into refineries and lighting the fire underneath.

Step 3: Each burning process takes 24 to 30 hours.

Step 4: Extracting gasoline at temperatures between 80 to 110 degrees.

Step 5: Extracting kerosene at temperatures between 120 to 320 degrees.

Step 6: Extracting diesel at temperatures above 320 degrees.

Step 7: Each 70 tons of crude oil produces approximately 270 barrels of diesel (each barrel holds 220 liters).

Step 8: Charcoal and slag remain as residues from the burning process. Charcoal is reused in the burning process, but slag accumulates without any use.

Step 9: Al-Anwar company monopolizes the purchasing process, buying the diesel and selling it to gas stations. Currently, the refineries only produce diesel.

A deadly job opportunity

Walid used to work in refining fuel in Tarhin, and he got used to the effects of toxic gas emissions, foul odors, and the dirt covering his hands and entire body. He told Enab Baladi that the most annoying thing for him is the irritation and redness of his eyes.

Walid answered questions about the effects of working in refinery sites with sarcasm, saying he has gotten used to the harmful emissions, shortness of breath, cracks in his hands, and the black color that has stained his hands for years. He pointed out that whoever enters the burners feels like they are dying and cannot bear the atmosphere.

The young man explained to Enab Baladi that one of the biggest challenges facing burners workers is the extreme heat and flames emitted from them. The most dangerous thing that a worker could face is swallowing one’s tongue during work, which could be fatal, along with the explosions and fires that occur from time to time.

Walid works with his three brothers in refining fuel to meet the needs of their nine-member family. He is displaced from the town of al-Safira in eastern Aleppo and has no other options. He has been operating the burners and burning crude oil to produce diesel for five years.

He told Enab Baladi that their work requires great effort, lasting from 20 to 45 hours per each burning process in the refinery. Each worker receives ($75) per burning session.

He mentioned that burners workers operate without basic safety equipment like protective clothing, gloves, and helmets, exposing them to extreme risks from heat and fire.

The pay for this job is high compared to other jobs, as daily workers in northern Syria earn about 100 Turkish lira at best (around $3). This amount is low compared to the needs, considering the poverty threshold is 10,378 Turkish lira, and the extreme poverty threshold is 8,984 lira.

Unemployment rates in northwestern Syria among civilians have reached an average of 88.79% (including daily workers in the mentioned categories), while 5.1 million people live in the area.

Operating burners to obtain diesel is a tough and complex job that requires withstanding extreme heat, fire risks, and dealing with the gases and smoke produced during the burning process.

147 Fires within a year and a half

According to statistics obtained by Enab Baladi from the Syria Civil Defence team (The White Helmets), firefighting teams responded to 105 fuel-related fires in the Tarhin area during 2023.

These were distributed between 99 fires at fuel refining stations and six at fuel stations, resulting in seven workers being injured with burns.

From the beginning of 2024 until May 27th, Civil Defence fire fighting teams responded to 42 fuel-related fires in the Tarhin area, all at fuel refining stations, leading to four workers being injured with burns.

Regarding the difference or danger of burner fires compared to those in other areas like camps or agricultural lands, the Syria Civil Defence volunteer Hassan Mohammed told Enab Baladi that the hazardous nature of burner work and the lack of safety measures make them prone to explosions at any moment, especially when temperatures rise, posing a significant danger to firefighting teams.

Mohammed added that dealing with petroleum fuels, in general, is dangerous and requires high training and expertise, but the situation in burners is highly complicated due to the risk of fire and explosion from the pressure.

The rapidly flammable gas emitted complicates things further, and the lack of proper technology for its utilization requires Civil Defence teams to take a long time to control the fires. Moreover, storing fuels near refining areas and the proximity of burners to each other increase the risk, according to the volunteer.

Death in Tarhin’s memory

The Tarhin burners carry the scent of death in the memory of workers and survivors of explosion incidents or attacks by Syrian regime forces and Russia. One of the notable incidents occurred on March 5, 2021, when regime forces and Russia shelled the fuel market in al-Hamran village and the primitive refineries in Tarhin village with seven ground-to-ground missiles carrying cluster bombs.

The attack resulted in the death of four civilians, including a Syria Civil Defence volunteer during fire response and extinguishing efforts. Forty-two civilians were injured, and there were significant material damages to civilians’ properties and fuel transport vehicles, with fire suppression efforts lasting 20 hours.

On February 9, 2021, regime forces and Russia targeted the oil burners in Tarhin village with a ground-to-ground Tochka missile carrying cluster bombs, killing two civilians and injuring four others.

Soil pollution: The hidden danger

Prof.Dr. Miassar Alhasan

Sham University Rector in Aleppo Countryside

Soil degradation is a global problem, and soil pollution is a danger that affects the environment with all its components. It poisons food, water, and air, posing a threat to human health and food security.

By its nature, soil has a great ability to filter and store pollutants, reducing their negative effects on plants, animals, and humans. However, this ability is limited and cannot regenerate endlessly.

With the aggravation of climate change and increasing desertification, most countries are actively assessing the health of their soil to identify pollutants that cause its degradation and affect their citizens’ health. Most soil pollutants originate from human activities such as industry, agricultural practices, and waste accumulation, in addition to the destructive impact of military operations on infrastructure and the harm caused by exploded and unexploded munitions.

The conflict in Syria has divided its geography into isolated control areas, preventing the flow of vital products between them, especially fuels that drive the economy. This reality has led to chaos in the fuel trade, manifested in the creation of marketplaces for fuel and diesel. These are dirt yards (often set up in agricultural areas) where tanks line up to offload their cargo into smaller trucks carrying metal or plastic barrels.

This results in thousands of liters spilling onto the soil, turning it dark or black, indicating saturation with heavy oils. This situation has also led to the creation of primitive oil refining stations, which have spread across northwestern Syria, polluting its soil over the years and causing significant environmental harm, especially to the soil, before most were shut down by local authorities or targeted by Russian and regime airstrikes.

Nevertheless, dozens of primitive burners continue to operate in the al-Bab area, especially in Tarhin village, known as one of the most polluted areas in northwestern Syria. This area already suffers from pollutant accumulation from sewage, crop burning, shelling, excessive fertilizer use to compensate for nutrient deficiencies in the soil, and more.

The problem is not new; even before the war, Syria’s soil suffered from deforestation, overgrazing, desertification, sewage irrigation, and inadequate disposal of oil refining waste. However, the issue has worsened since primitive oil burners became integral to the economy of northwestern Syria, with their effects still lingering in the soil. No action has been taken to clean the accumulated pollutants, especially since oil pollution poses a significant risk to public health.

Understanding the nature of this risk in each area requires conducting in-depth regional soil studies and placing the results in a regional context. For accurately assessing the soil condition in northwestern Syria, limited data availability impedes clear conclusions.

In a region already suffering from regional drought and extreme pressure on water resources, the economy and infrastructure collapse due to the war has led to the spread of unregulated industries such as electroplating and tanneries, harmful agricultural practices like irrigation with sewage and poor-quality fertilizers. These practices are classified as indirect environmental effects of the conflict, exacerbating its direct impacts from aerial and artillery bombardment and the spread of explosive and unexploded ordnance and military operations.

Naturally, priority is given during battles to rescuing civilians, retrieving victims, and treating the injured. However, with the prolonged war, the environment becomes the major victim, as neglecting it causes a comprehensive humanitarian disaster due to the damage to the soil and water, which are the primary food sources for the population. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), non-degradable weapons and chemicals from wars can remain in the soil for many years.

Europe has not escaped the destructive impact of conflicts, as World War I caused severe environmental damage from deforestation and using millions of tons of weapons and ammunition, some of which remain in the soil, making some areas uninhabitable even today (over a hundred years later), such as the Red Zone in France.

The Gulf War of 1990-1991, during which oil wells were targeted, caused severe environmental damage. It significantly harmed desert reserves, accelerating soil erosion, increasing sand movement, and spreading dust and sandstorms.

The Iraq invasion in 2003 also caused catastrophic effects on the soil due to the construction of military fortifications, laying and removing minefields, and the movement of tens of thousands of military vehicles.

Soil pollution is simply defined as the presence of certain elements in it at levels exceeding the natural range, which varies from country to country.

While Europeans have agreed on common reference values, each country adopts specific legislative values for these levels, aligning with its human, economic, and even political considerations, in addition to its geological reality, which can explain increased concentrations of certain elements in deeper soil layers.

Syria belongs to the third Arabian plateau, consisting of clay, marl, limestone, sandstone, and local volcanoes (basalt), with a tectonic layer extending to the west, northwest, and north (General Directorate of Geology). This deep layer significantly reduces the impact of increased concentrations of heavy metals in the soil.

To successfully plan, implement, and accomplish soil decontamination from pollutants in general and fuel residues in particular, a deep understanding of pollution sources and severity is necessary.

This understanding is based on the availability of regional and local reference data. A study titled “Toxic elements in the soil of north-west Syria following a decade of conflict” supported by the James Hutton Institute has contributed to meeting this need by reporting the first coordinated survey of surface soil concentration across northwestern Syria for potentially toxic elements.

The study raised high levels of toxic heavy metals like arsenic, cobalt, chromium, and nickel in the al-Bab area, significantly exceeding global and European levels. The study also reported a marked change in soil texture and physical properties in this region.

Current efforts to restore the environment in northwestern Syria should focus on three main challenges:

Continuous risk analysis: Assessing risks threatening residents’ health due to soil pollution, requiring regular soil sample testing and establishing a database to monitor pollutant levels based on consistent records. The European Union’s LUCAS (Tóth et al., 2016) surface soil survey protocol could be an appropriate reference for this analysis.

Collaborative efforts: Institutions and organizations should collaborate to develop crop varieties resistant to climate change and increased soil pollutants, implement partial irrigation and solar distillation in agriculture to manage water quality and reduce demand on contaminated water, and contribute to regional environmental recovery.

Sustainable soil treatment: Exploring the possibility of treating contaminated soil using sustainable, low-cost methods, such as biochar and phytoremediation in addition to bioremediation.

The latter remedy is especially useful for treating oil pollution by providing special microbes (bacteria and fungi) that naturally break down oil (as a hydrocarbon substance) within a controlled microbial community, with regulated temperature and ventilation to speed up the biodegradation process, along with continuous monitoring of its levels.

Each soil needs a specific treatment method based on its location, contamination level, oil concentration, and proximity to groundwater. It is not advisable to scrape contaminated soil and replace it with new soil, as this merely shifts the problem rather than solving it fundamentally.

The idea of bioremediation is not new but remains limited in application. The United Nations Environment Programme launched a project to clean contaminated soil in Kirkuk with oil spills in 2017. It involved collecting 20,000 tons of oil waste into ten large pits and decomposing them by adding soil nutrients, substances to increase soil aggregation, and improving oxygen and water content to create conditions conducive to bacterial growth, which naturally accelerates hydrocarbon breakdown. Progress was slow, but the Iraqi Ministry of Environment estimated the success rate at 77%.

The time required for soil purification depends on the contamination level, contaminated area size, cleaning technologies used, funding and resources allocated, making it difficult to determine a specific duration. Environmental scientists use the term “Soil Pollution Mitigation,” indicating the difficulty (or perhaps impossibility) of restoring soil purity to its original state over many years, such as in France’s red zone. These mitigation actions are divided into short-term and long-term measures.

Plants are also affected by air pollution from increased concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrogen oxide (N2O), emitted from industrial sources, greenhouses, and more.

The problem with gases emitted from oil burners is their extreme concentration, doubling the risk to nearby agricultural crops and trees. A thorough scientific study to assess air pollution’s impact on agricultural crops has not been dedicated yet.

Generally, air pollution damages plant leaves, reducing their ability for photosynthesis and significantly lowering their productivity and crop quality. Gases emitted from burners are especially laden with particulate matter (PM) and black carbon, severely impacting crop productivity.

Tackling soil pollution requires joint efforts from individuals, institutions, and civil society organizations due to its cumulative effect on the environment, economy, public health, and society. Although Tarhin is currently the most polluted area with oil residues, we cannot confirm that we have surpassed the harmful effects of the stopped burners in the absence of comprehensive data on soil, water, air quality, and residents’ health from hospitals and health centers.

Thus, we need to encourage researchers and university students to provide innovative solutions, promote institution-university-organization cooperation to establish a local soil-water-air pollution monitoring network, and create a shared database that allows for an understanding of the environmental reality and the formulation of a comprehensive environmental restoration plan in our region.Breathing cancer

Inhaling toxic gases poses endless risks, ranging from coughing to cancer or diseases affecting the kidneys and heart. The fumes and emissions from burnoff processes contain high levels of particles and heavy metals produced by burning oil, which affect all body organs.

Dr. Aula Abbara, an infectious diseases consultant in London and head of the Syrian Public Health Network, told Enab Baladi that the toxic materials and elements in the air emitted from burnoffs can have negative effects on health, especially the lungs, in terms of higher rates of respiratory infections, bronchitis, and lung cancer noted in some studies evaluating the health of workers and residents near oil refineries.

She added that the situation would become worse if workers did not receive adequate protection during their work. The toxins from pollutants, such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, and carbon monoxide, pose an accumulative health risk over the years, especially for those working in or near the refinery.

However, it is generally difficult to prove causation when diseases are observed near an oil refinery. This could be significant, for example, in cases of cancer, heart diseases, or neurological disorders that also have other risk factors.

Regarding the short and long-term diseases that these gases can cause, Dr. Abbara said research indicates that there might be direct or indirect effects. Pollutants can irritate the eyes and skin of those working or living near oil refineries.

Evidence suggests the main diseases caused by these unregulated refineries are linked to lung health, such as bronchitis and lung cancer, but they are also implicated in causing other types of cancer, neurological damage, and heart and blood diseases.

There are also indications that they may cause birth defects and lead to negative pregnancy outcomes. However, not all research is consistent, and proving cause and effect can be difficult, according to Dr. Abbara.

Other research suggests that living near an oil refinery can also adversely affect mental health due to the psychosocial pressure of living near the refinery.

Noting that smoking rates in Syria are higher than those in other regional countries and that the general health of the population has been affected by prolonged conflict and limited access to healthcare, there might be an additional impact from environmental pollution caused by oil refineries, especially when regulations and governance are weak, according to Dr. Abbara.

Workers in these refineries often have no choice but to work there in a country with high poverty and unemployment rates, even if they suspect risks to themselves and their families, according to Dr. Abbara.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the US Department of Labor, the effects of oil spills and working with them are a source of epidemics and cause of death, with consequences and impacts varying depending on the type of gases and substances emitted.

The harms from working in oil spills, based on the emissions of carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide, methyl tertiary-butyl ether, sulfuric acid, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and others include:

Coughing, drowsiness, irritation of the eyes, skin, respiratory system, and teeth, dizziness, rapid heartbeat, headaches, tremors, loss of consciousness, anemia, skin or lung cancer, high blood pressure, asphyxiation, coma, nausea, nervous system, liver, and kidney impairment, negative effects on reproduction, the immune, digestive, and nervous systems, severe tissue burns, and loss of balance.

With the large number of refineries that have operated or still operate, thousands of civilians, including many children and adolescents, have been exposed to hazardous materials and harmful fumes for long periods, which can have long-term health consequences, according to an investigation conducted by Wim Zwijnenburg, Head of the Humanitarian Disarmament Program at the Dutch organization “PAX” in April 2020.

According to the investigation, working all day amid harmful fumes from burning oil, rubber, and refined gasoline has resulted in thousands of people, including children, suffering from severe acute respiratory problems, skin issues, and inflamed wounds, while those exposed for long periods may suffer from internal organ damage due to the accumulation of toxins in the body.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News