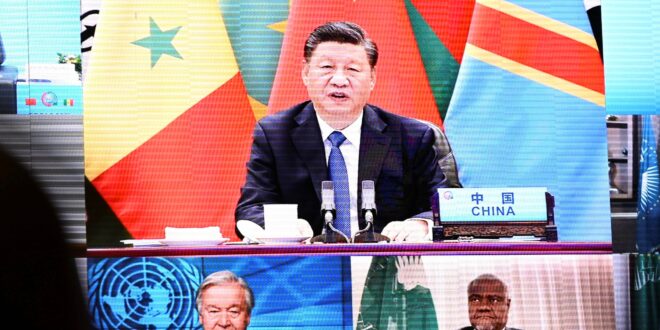

At the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation starting September 4, Beijing will once again seek to deepen its engagement with countries in the Global South. Chinese leader Xi Jinping was, to his credit, prescient in recognizing the frustrations and aspirations within the developing world and has capitalized on those sentiments to build China’s global political and economic influence. The three-day event, which the Chinese foreign ministry called “the largest diplomatic event China has hosted in recent years,” is only one of a series of programs, initiatives, and gatherings that Beijing has launched to tighten its bonds of diplomacy, business, and trade with countries throughout the Global South.

Yet over the past two years, Xi’s approach to the developing world has undergone a significant change: It has become increasingly consumed by Beijing’s geopolitical competition with the United States and its allies and partners. This shift will have major consequences for Beijing’s relations with the Global South, China’s role in the international order, and the future course of its global power.

The aim of Xi’s strategy is to build a coalition of states within the Global South to act as a counterweight to the US global alliance system and a base upon which to promote China’s political, economic, and ideological interests. Xi wants to undermine the US-led rules-based international order by creating a Chinese-led alternative order based on illiberal political principles that can roll back US influence and shape global governance through international institutions and forums.

This goal has elevated the importance of the Global South in Chinese foreign policy. Countering Xi’s ambitions will require Washington to devote greater diplomatic and financial resources to and focus more attention on the developing world, as well as to promote its own vision for more inclusive global governance within the existing liberal international order.

What drives China’s Global South outreach

The change in Beijing’s approach to the Global South is part of Xi’s growing anti-Americanism, which is shaping most aspects of his policy program both at home and abroad. Xi’s increasing focus on economic “self-sufficiency” and the development of homegrown technologies through state-led industrial programs is designed to eliminate China’s vulnerabilities to potential sanctions from Washington. Domestically, Beijing’s heightened concern about foreign threats and influence has led to new security regulations that are intensifying repression and alarming the international business community. In his foreign policy, Xi has more overtly challenged the US-led order by, for instance, promoting his own ideological framework for reshaping global governance with his Global Security Initiative and Global Development Initiative.

The motivations for Xi’s policy toward the Global South are similar—to protect China’s security and promote Chinese global interests in an environment of heightened competition with the United States. Initially, Xi’s primary purpose in his approach to the Global South was to foster Chinese political and economic connections with developing countries to promote China’s global interests. His Belt and Road Initiative, announced in 2013, was crafted to strengthen trade, finance, and investment between China and the Global South and pursue Chinese business interests in emerging markets. China’s involvement in and promotion of forums such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization is also aimed at fostering such ties, as well as enhancing the voice of developing countries in international affairs. With all these initiatives, Xi intended to paint China as an alternative to the United States and its partners and as a champion of the interests of the world’s poorer nations.

Xi’s confrontational shift

A shift in Xi’s approach started to become apparent with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. By forging a “no limits” relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin in February 2022—as Russia’s army was poised on its border with Ukraine, preparing to invade—Xi made a fateful choice: to pursue a more overtly confrontational stance toward the United States and its allies and partners that would inevitably open a deeper divide between China and the allied democracies. Once Putin’s tanks rolled into Ukraine three weeks later, that outcome became unavoidable. The invasion galvanized NATO and the United States’ security partnerships with Indo-Pacific nations, allowing US President Joe Biden to bridge some of the differences within these alliances regarding policy toward China.

As a result, the United States and its partners in Europe and the Indo-Pacific have forged a far more coordinated and coherent stance on China policy. The more Xi has sought stronger relations with Putin, even as the war in Ukraine has dragged on, the tougher US allies’ policy toward China has become. During the most recent Group of Seven (G7) summit, for instance, its leaders collectively warned China to cease assistance to Russia that supports Moscow’s war effort or face sanctions.

Xi’s decision to throw his lot in with Putin was a conscious choice, not one forced upon him. Before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the leaders of Europe were hardly of one mind on China, and not entirely aligned with Washington’s position. Beijing had been making progress in exploiting these rifts to divide the United States and its European allies on issues regarding China. Though Xi continues to make some effort at dividing the allies—he appears to have identified French President Emmanual Macron as a weak link—his partnership with Putin has made that task significantly more challenging, if not outright impossible.

Xi has been willing to break with the United States and its allies to further a larger goal: undermining the current international order. He apparently sees Russia as a crucial compatriot in this quest. “Change is coming that hasn’t happened in a hundred years,” Xi told Putin during a visit to Moscow in 2023. “And we are driving this change together.” Putin can also aid Xi in his pursuit of other aspects of this anti-American agenda. For instance, Russia is providing a secure source of energy imports and a key market for Chinese manufactured exports safe from the sanctions and protective barriers imposed by the United States and other advanced economies, thus furthering Xi’s goal of reducing his country’s vulnerabilities to Washington’s policies. Deepening ties with Russia was a core element of that wider shift in his foreign policy toward a more confrontational stance against the United States.

Building blocs

That same thinking has infected Xi’s overall strategy in the Global South. No longer content to simply build influence among developing countries, or even present China as an alternative, he is now seeking to enlist their leaders into his anti-American movement. This agenda is most apparent in the progress of the BRICS group of developing nations. Originally based on a concept fashioned by investment bank Goldman Sachs, the forum was meant to encourage greater cooperation among what were supposed to be the world’s major up-and-coming economies—Brazil, Russia, India, and China. (South Africa was added later.) Last year, Xi successfully pushed for an expansion of the group’s membership. Keeping to the initial spirit of the forum, some obvious candidates come to mind. Indonesia stands out, as do other Southeast Asian nations, such as Thailand. Nigeria is a strong possibility, as well. Yet those countries were not invited. Instead, the group approved the inclusion of two Middle Eastern energy exporters (Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), an isolated Iran, an economically troubled Egypt, an extremely poor Ethiopia, and Argentina, a country in almost perpetual financial turmoil.

What these countries have in common is that China has economic or diplomatic leverage over them, or it wants to entice them into tighter partnerships. Egypt and Ethiopia both have close political ties to China—and heavy debts to Chinese lenders. Beijing is helping Egypt build an entire new capital city. Iran, under Western sanctions, is, like Russia, reliant on Chinese diplomatic and economic support. At the time of the expansion, Argentina was avoiding a default on loans from the International Monetary Fund by tapping funds from China’s central bank. And Beijing is clearly wooing the Saudis and Emiratis as partners in the Middle East. Xi most likely intends for these same countries to support Chinese foreign policy goals and interests, not only within the BRICS, but also in other forums and initiatives. At the most recent Belt and Road Forum, held in October 2023 in Beijing to celebrate the program’s first decade, leaders from three of the BRICS—Russia, Ethiopia, and Argentina—spoke at the opening ceremony.

In other words, the BRICS expansion was designed to pack the forum with countries that will potentially support Xi’s anti-American agenda and help him turn that group and others into alternatives to the G7 and other US-influenced international forums. Beijing persistently stresses that the BRICS countries should unify behind an agenda to promote the interests of the Global South—and China. At a BRICS meeting in June, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi stressed that the expansion of the group’s membership would usher in “a new era for the Global South to gain strength through unity,” according to a summary of his comments published by the Chinese state news agency Xinhua. The summary went on to say that Wang urged the BRICS nations to stand against “politicization and securitization of economic issues and increasing unilateral sanctions and technological barriers”—all of which is code for US policies that Beijing opposes.

But Xi faces challenges. One indication of that is the decision by Argentina’s new president to reject the invitation to join the BRICS. The more Xi’s anti-Americanism drives his policies, the more Beijing’s relations with the developing world could come under strain. Inherently, and openly, Beijing is pressuring governments of the Global South to take sides against the United States. For instance, Beijing has come to expect the leaders of the developing world to publicly approve of the Global Security Initiative, the principles of which run counter to the ideals and practices of international affairs favored by the United States and its allies. In the run-up to the Ukraine peace summit held in Switzerland in June, which China refused to attend, Chinese diplomats reportedly pressured developing countries to support a Chinese alternative peace proposal. One diplomat called this effort a “subtle boycott” of the peace conference, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy publicly accused China of helping Russia sabotage the summit.

A better US approach to the Global South

Washington has been guilty of similar behavior, but US policymakers have come to understand that such “with us or against us” methods can backfire with members of the Global South intent on charting an independent course in world affairs. That realization is evident in the Biden administration’s flexibility in relations with India, for example. If China’s approach to the Global South attempts to force its political elites to take sides, Beijing could undermine its own efforts to woo their support. Some countries may willingly join Beijing’s anti-American agenda, such as Russia and Iran, both of which are already alienated from the West. Most, though, benefit too much from their ties to the United States to risk severing them.

Pressing Global South governments to take positions against Washington could also sour public opinion toward China within the developing world. In a recent survey in Thailand, a similar share of respondents (about three-fourths) felt that the United States and China do more good than harm to security in Asia, an indication of the balanced views held by people in that important Southeast Asian nation even as competition between the two powers intensifies.

Xi’s escalating anti-Americanism has also led him to make strategically questionable decisions. Beijing rejected Washington’s appeals to join an international coalition to quell the turmoil in the Red Sea caused by the Houthis, who have been preying on shipping passing through the Suez Canal. Beijing’s inaction appears to be motivated by its preference to use the Red Sea crisis to attack US policy in the Middle East. A Chinese envoy to the United Nations linked the situation in the Red Sea to the conflict between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, signaling that the unrest in the region is a consequence of US foreign policy. The cost, though, could be undermining Beijing’s claim to be a more responsible player in the Middle East than the United States and irritating important partners who do not support the Houthis, such as Saudi Arabia.

The leaders of the Global South will surely be sensitive to China’s attempts to use them as tools in a geopolitical game against the United States. That potentially opens opportunities for Washington to present the United States as more inclusive by encouraging greater North-South dialogue. Efforts to elevate the voices of the Global South’s political elites in the governance of the current world order could go a long way toward countering a China that has become more intent to enlist them in a campaign against that order. The Biden administration has already tried to make progress in this direction with initiatives such as the Partnership for Atlantic Cooperation, which includes more than thirty countries bordering the Atlantic Ocean.

But much more can be done. For instance, a further expansion of the Group of Twenty (G20) to enhance the representation of the Global South—already begun last year with the inclusion of the African Union—should be considered. Additionally, the G7 could create more formal forums to address North-South issues. In these efforts, Washington should avoid creating the impression that choosing to participate in US-led initiatives precludes interaction with China. Trying to convince the Global South to be anti-China would likely be as counterproductive as Beijing’s new efforts to make it anti-American.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News