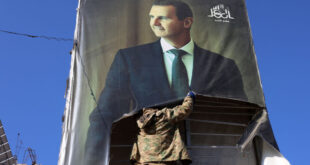

The dramatic fall of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad has sent shockwaves across the Middle East and beyond, marking the end of a 24-year rule and raising questions about the future of Iran’s regional influence.

For over a decade, Syria has been a critical node in Tehran’s so-called “Axis of Resistance,” a network of like-minded armed groups designed to counter Western and Israeli influence.

Al-Assad’s ouster was driven by a coalition of opposition forces who seized Damascus. On Sunday, after 13 years of civil war that fractured the country, the Syrian regime, once bolstered by Russian and Iranian support, crumbled.

Opposition fighters declared Damascus “liberated” in a statement aired on Syrian state television. Al-Assad fled to Russia, accompanied by his family, where he was granted asylum. A Kremlin spokesperson said on Monday that Moscow would not disclose his whereabouts.

The rapid opposition advance over just 11 days reignited a conflict that had been largely static since 2020, marking the conclusion of more than 50 years of autocratic rule under the al-Assad dynasty.

“Hayat Tahrir al-Sham” (HTS), a Sunni group once affiliated with al-Qaeda and labeled a terrorist organization by the US and UN, spearheaded the rebellion. It operated alongside other factions, including the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, the latter being a source of contention with Ankara, which views the group’s growing influence as a threat to its regional security and interests.

The al-Assad family’s grip on Syria was synonymous with repression, defined by widespread reports of human rights abuses, mass incarceration and systemic torture.

The speed of al-Assad’s ouster caught global powers off guard.

For Iran, al-Assad’s removal represents the loss of a key ally and the fragmentation of its carefully constructed sphere of influence in the Middle East. The future of Tehran’s regional strategy now hangs in the balance.

‘Axis of Resistance’ under pressure

For 13 years, Tehran committed substantial resources – both financial and military – to uphold the al-Assad regime. However, this investment unraveled within days as opposition forces swept through Syria, capturing city after city.

Syria served as Iran’s most crucial regional partner, offering a vital land corridor for supplying Hezbollah with arms, funds and training. Now, the infrastructure that supported Hezbollah’s logistical operations has been disrupted, with severe implications for Iran’s power projection in the region.

Hezbollah has been battered by 14 months of war with Israel, which killed the group’s top leader Hassan Nasrallah and other senior commanders.

Similarly, Hamas, another Iran-backed group, suffered significant setbacks by more than a year of war set off by its October 7, 2023 attack on Israel, including the deaths of its leaders.

Iran’s web of proxies includes militias in five countries: Lebanon, Syria, the Palestinian territories, Iraq and Yemen.

Analysts argue that without Syria, the alliances Tehran has nurtured for decades will disintegrate. At the same time, with the ongoing threat of Israeli airstrikes targeting weapons bound for Lebanon, it seems unlikely that Iran can retain this critical supply route. Its capacity to rebuild Hezbollah and sustain its influence appears in jeopardy.

“The fall of Assad deals a heavy blow to Iran’s regional influence and undermines its ability to maintain the Shia crescent in the Arab world using previous tactics and tools,” said Ali Bakir, assistant professor at Qatar University and nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

“The centrality of Syria is crucial not only for maintaining Iranian influence and support for its Lebanese proxy but also for keeping the Shia corridor interconnected in a way that projects Iran as a regional power,” he told Al Arabiya English. “The loss of Syria exceeds Tehran’s capacity to recover, at least in the short term.”

Beyond these immediate military and logistical challenges, Iran’s reliability as a regional partner has taken a hit, said Syga Thomas, a former US diplomat and CEO of Ensah Advisory Partners, an advisory firm offering geopolitical insights.

“This erosion of trust could embolden rivals like Turkey to intensify their efforts to curb Tehran’s influence,” he added.

Iran’s direct attacks on Israel earlier this year failed to deter its arch-foe and instead exposed weaknesses.

In October, Iran fired about 200 ballistic missiles at Israel – the largest direct strike in their decades-long shadow war – but most were intercepted by Israeli, US and allied defenses. In retaliation, Israeli forces penetrated Iran’s air defenses, leaving Tehran vulnerable to further Israeli action.

As Iran’s influence wanes, Israel is becoming the dominant force in the region.

To protect its interests, Thomas notes Tehran might look for alternative routes to support Hezbollah, perhaps through Iraq, while using its influence there to shore up its position.

“Regionally, Iran could strengthen its ties with Russia or China to counterbalance Turkey and Israel, while continuing to use asymmetric tactics – like cyberattacks and proxy forces – to disrupt its rivals and keep itself relevant in the shifting power dynamics,” he said.

Some speculate that Iran may attempt to forge a partnership with Syria’s new leaders, proposing collaboration against Israel and the US. However, it remains uncertain whether groups targeted by Iranian-backed al-Assad over the past years would be willing to cooperate.

Iran has opened a direct line of communication with opposition forces in Syria’s new leadership, a senior Iranian official told Reuters on Monday, in an effort to “prevent a hostile trajectory” between the countries.

A hostile post-Assad Syria would deny Iran its main access to the Mediterranean and the “front line” with Israel.

Domestic criticism

The overthrow of al-Assad has sparked domestic criticism within Iran, with even supporters questioning the rationale behind Tehran’s costly intervention in Syria and the billions spent on a network that fell apart so quickly. Critics have highlighted the financial and human cost of the policy.

Iran reportedly spent an estimated $50 billion to prop up the Syrian regime during the civil war, according to a leaked government document published by an Iranian opposition group. The intervention also claimed the lives of many officers as well as senior commanders of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

“At present, Iranians are reevaluating their regime’s past policies, particularly the years spent investing in and supporting the Assad regime against its own people,” said Bakir. “This led to the killing of hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians and the displacement of over 12 million Syrians, only for the regime to collapse and potentially pivot toward an anti-Iran stance in the future.”

Balance of power among rebel factions

Many in Syria are celebrating the unexpected political shift, but this change is also clouded by uncertainty. There are concerns that while al-Assad’s fall weakens Iran, it may fuel a resurgence of extremist factions.

Western and Arab nations fear that the HTS-led opposition coalition may seek to replace al-Assad’s regime with a hardline Islamist government, or one less able or inclined to prevent the resurgence of radical forces, Reuters reported citing sources.

Opposition leader Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, now using his real name Ahmed al-Sharaa, began on Monday discussions on transferring power.

He met with Prime Minister Mohammed al-Jalali “to coordinate a transfer of power that guarantees the provision of services” to Syria’s people, said a statement posted on the opposition groups’ Telegram channels.

Experts note that while HTS led the offensive that toppled the al-Assad regime, other opposition factions also played a role and will seek a say in Syria’s future.

“In southern Syria, groups under the Southern Operations Room moved swiftly as the regime retreated, reaching Damascus’ outskirts ahead of others. The Syrian National Army factions also launched an offensive in Eastern Aleppo, supporting HTS as it moved southward,” Broderick McDonald, a conflict researcher at King’s College London, told Al Arabiya English.

“Though HTS is the most organized, it will need to work with other groups and sectors of society for a stable, representative government.”

McDonald warned that if al-Jolani attempts to consolidate power in Damascus as he did in the city of Idlib in northern Syria, the country’s future could be bleak.

“HTS’ lack of legitimacy, both among minorities and internationally, presents a major challenge. Any future Syrian government must be inclusive to succeed long-term,” he added.

Al-Jolani has gone to great lengths to reassure Syria’s Christian and Kurdish communities as HTS offensive expanded. He aims to present himself as a moderate figure capable of uniting Syria’s factions and rebuilding institutions to replace the ousted dictatorship, but the reality is more complicated, given that currently HTS lacks legitimacy and has limited ties to the outside world.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News