Trump’s victory was cheered by populists across Central Europe, but his return looks anything but good news for regional economies already faltering as they enter 2025.

The economies of Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia are among the most vulnerable in the EU to the repeated threats by incoming US president, Donald Trump, to slap tariffs on imports from Europe, China and elsewhere. He has mentioned tariffs of anywhere from 10-20 per cent for European exports.

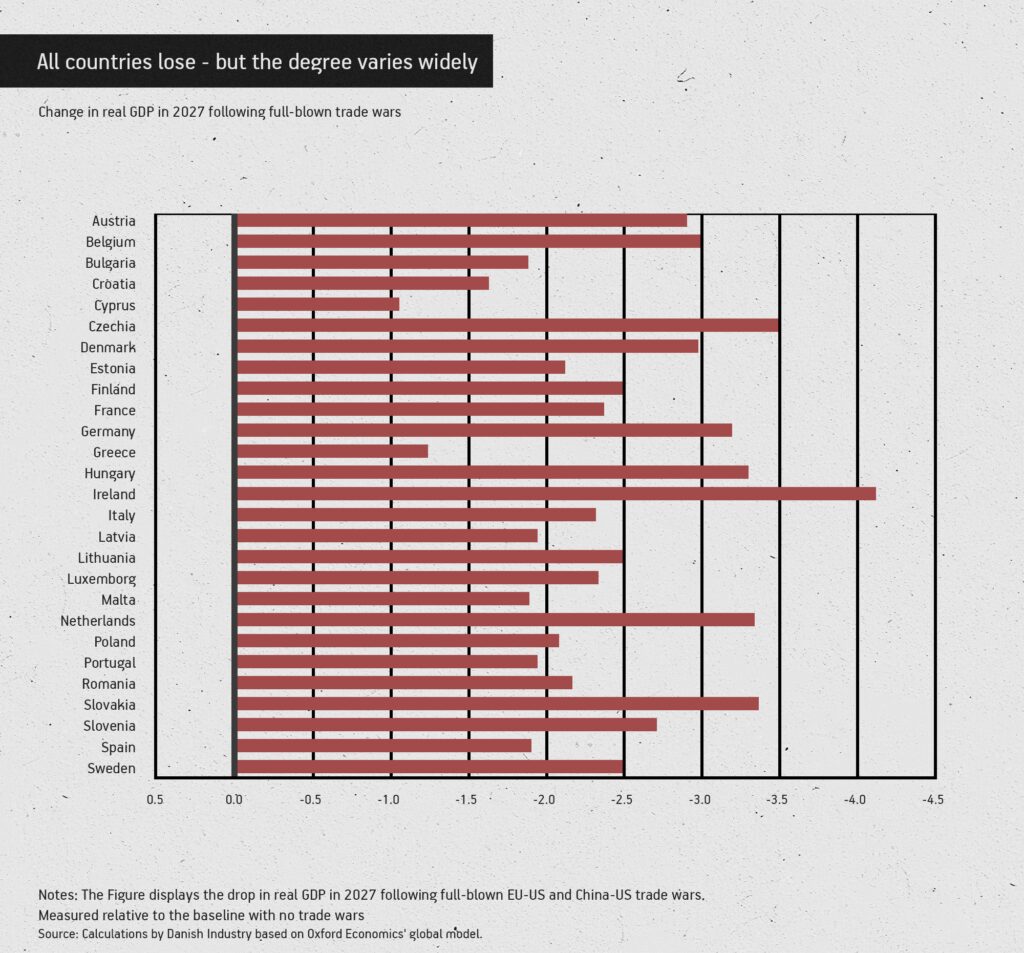

According to a report by the Confederation of Danish Industry, there would be significant variation in GDP declines across EU countries in the event of a full-blown trade war, though the heavy dependence of the Visegrad Group (V4) on exports, in particular via their role in the supply chains of European carmakers, puts them at risk of losing 2.0 to 3.5 per cent in GDP from US tariffs.

The Czech Republic and Ireland would be among the hardest hit, with GDP dropping by up to 4 per cent.

“[Our] analysis, using Oxford Economics’ global model, examines how these tariffs, implemented in 2025, would affect European economies. The impact is severe, with GDP expected to drop by as much as 2.5 per cent by 2027. This corresponds to 391 billion euros or 870 euros per capita. Further, employment drops by 0.7 per cent, corresponding to 1.7 million jobs,” the Confederation of Danish Industry said.

- Overview

Beset by low confidence and sluggish demand from Eurozone trade partners amid the war in Ukraine, the V4’s export-driven economies are clearly highly exposed to the incoming US president’s threats to start a trade war.

During his election campaign, the Republican candidate railed against the unfairness of exporters to the US, and promised to continue the crusade partially launched during his first stint in the White House by imposing high import duties. The idea is presented as a means to protect US workers, although most economists suggest they’ll do little, save for making life more expensive for consumers.

Regardless, the populist pledge helped get Trump across the electoral finish line, and having declared tariff “the most beautiful word in the dictionary”, he has global economies braced for a potential storm.

Trump announced a levy of 25 per cent on Canadian and Mexican imports as well as an additional 10 per cent tax on Chinese goods would come into force on February 4. Dauntingly for the V4 – Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia – he also has a bee in his bonnet about those countries’ main trading partner, Germany.

Many hope the famously erratic billionaire will prove open to wheeling and dealing to win carveouts, just as he was in his first term. That suggests Europeans could boost purchases of US liquefied natural gas (LNG) or raise defence spending – ideally with outlays on US weapons – in order to sidestep a trade war. With this, and Washington’s support for Ukraine in mind, Europe’s NATO members have discussed increasing their target for defence spending to 3 per cent of GDP from the current 2 per cent. However, Europe is already a big buyer of US gas and military equipment, leaving limited room for dealmaking.

Some suggest Trump could ignore his election pledge to punish freeloading Europeans and instead look to protect his legacy by avoiding the economic damage that tariffs would cast on the US economy, and are looking closely at his trade and economy appointments. “Trump is a dealmaker,” says Marieke Blom, chief economist at ING Bank, “ergo, it seems reasonable to assume he will make deals. And, judging from his last administration, American corporates might be able to convince the president-elect of the negative impacts on their businesses.”

Even amid such hopes, the uncertainty will inevitably inflict some damage, deterring investment and hurting confidence. Growth forecasts for economies across Europe have tumbled since the US election in November 2024, with the outlook for the Eurozone, the V4’s main trade destination, turning even more anaemic due to heavy reliance on US trade. The US emerged as the leading destination for EU exports in 2023, accounting for 19.7 per cent of total exports outside the bloc.

Estimates suggest that in the event of a full-blown trade war between the US and EU, the V4 economies could take a hit of 2-4 percentage points from GDP in the ensuing years. “The long run costs will be higher for small, open countries which are particularly reliant on trade for the transfer of technological expertise and know-how,” say analysts at Capital Economics.

Although the V4 countries do not have high exposure to the US via direct trade, their economies are highly dependent on their role in the supply chains of Eurozone exporters. German factories are the main destination for V4 exports, and Germany’s high trade surplus with the US is a clear target for Trump. More specifically still, the V4 economies lean heavily on supplying parts for one of Trump’s longtime bugbears: German cars.

“They sell millions and millions of cars in the United States. No, no, no, they are going to have to pay a big price,” Trump said recently. He has even floated the idea of a 100 per cent tariff, which would put a huge dent in the 23.4 billion euros worth of vehicles Germany sold to the US in 2023. According to estimates, Trump’s tariffs could hit the German economy, the main engine of Central European growth, by 33 billion euros, or 1.5 percentage points, within two to three years.

The risk to the V4 is even larger. In 2023, Slovak auto exports that made their way to the US constituted 4.3 billion euros, or a full 3.5 per cent of GDP. Hungary’s dependence was at 3.2 billion euros, or 1.6 per cent.

“Donald Trump’s team appears fixated on certain industries and cars are at the top of that list. If US policy goes in that direction, then the three smaller V4 countries will be very exposed.”

– Richard Grieveson, Deputy Director of the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies

The Czech Republic’s car industry, which accounts for nearly a tenth of its GDP, over a quarter of industrial output and more than a fifth of exports, is already plagued by uncertainty due to the transition to electric vehicles. And its close links to other key industries, such as steel and chemicals, suggest the tremors could quickly spread throughout the region.

“The V4 economies are already struggling due to poor demand from the Eurozone,” points out Richard Grieveson, deputy director at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), noting that trouble for the region’s factories would swiftly threaten the strong wages growth currently underpinning the economies.

“For the moment it’s largely consumers, encouraged by fallen inflation and tight labour markets, that are keeping things on track,” Grieveson continues. “But that can’t last indefinitely, especially if conditions deteriorate due to US tariffs.”

Ironically, it’s Trump’s fanboys that look most at risk, and with fewest options to strike a deal. Despite Viktor Orban’s self-appointed role as the Republican’s head cheerleader in Europe, Hungary’s struggling economy, saddled with high inflation and empty government coffers, may be the most vulnerable to Trump’s tariffs, says Alberto Rizzi of the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

Hungary’s minister for trade and foreign affairs, Peter Szijjarto, said, rather optimistically: “Trump likes to negotiate and… we hope we will have a deal that is good for Hungary.”

That could be a stretch, especially given that, somewhat ironically, the anger Budapest’s policies have provoked in Brussels also appear designed to irk the capricious US leader. Hungary is the EU’s leading hold out when it comes to diversifying away from Russian gas, and is refusing to look at alternatives including US LNG. Orban has also forged deep trade links with China, which is the Trump administration’s number-one target. China was the source of close to 60 per cent of Hungary’s foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2023, as it poured 8 billion euros into the country mostly to expand or build new electric vehicle and battery projects. These factories would likely suffer in any EU-US trade war.

Yet that threat hasn’t prevented Slovakia’s Robert Fico, another leader who welcomed Trump’s return, from launching his own chase for yuan. Slovakia also continues to import Russian gas in volume.

To make matters worse, Slovakia alongside Hungary – and Czechia to a lesser extent – know full well that their parlous finances will make meeting the proposed higher NATO spending target tricky.

Poland – the sole Visegrad state whose government is not led or expected anytime soon to be led by Trumpist populists – is actually the least exposed to the US tariff threat and looks in the best economic shape to keep Trump happy. Thanks to its large domestic market, the Polish economy is far less dependent on exports than its Visegrad peers. Meanwhile, at 4.1 per cent of GDP in 2024, Poland’s defence spending is the highest in the EU and the country also purchases large volumes of US LNG. That has Prime Minister Donald Tusk marked down as a key figure to help broker EU relations with the Trump administration.

Exchange rate movements are reflecting the heightened risk. All local currencies have dropped in value against the dollar, while Hungary’s forint has hit new lows against the Polish zloty. “Larger markets like Poland will be able to maintain momentum for longer, but the other smaller V4 states would likely feel the effects [of a trade war] fairly quickly,” Grievson warns.

The rhetoric so far suggests that Trump will introduce at least some tariffs, “but that countries which co-operate with him will be able to head off more punitive surcharges,” suggest Capital Economics’ analysts.

But it also seems clear that any such tactic would only run so far, and for so long, in Trump’s transactional world.

Could the threat of a trade war, then, finally push the EU into serious action to raise its economic gain, as Mario Draghi recently called for in a report damning the bloc’s competitiveness? “Europe will have to stand on its own two feet in many areas, as Trump is likely to perceive the old continent primarily as a competitor, rather than a partner,” reckons Robert Stehrer at wiiw. “The EU would therefore be well advised to put its own competitiveness – especially that of industry – on a new, innovative footing, and finally pull together in terms of economic policy.”

Rizzi says that, in response, Brussels should immediately look at completing the single market and accelerate work on trade deals with other parts of the world. “The completion of the single market would bring big economic benefits – the EU is estimated to lose 10 per cent of its potential GDP due to remaining internal barriers – and would increase European resilience to economic challenges,” he insists.

Such a move would presumably be hugely popular among the V4, which have long seen free trade and open borders as the most vital elements of the bloc. However, the usual difficulties face the EU: endless bickering and a lack of unity amid domestic political interests.

“Trump’s administration will seek bilateral deals in order to split off EU states, in what will be both a tactical and ideological approach,” asserts Rizzi. “It will be up to the EU to resist.”

Little wonder then, that Ursula von der Leyen urged unity in her first speech as the re-elected president of the European Commission. But the signs so far have not been encouraging.

Von der Leyen quickly jetted off to seal a free trade deal with South American countries (Mercosur) that has been on the cards for over 20 years. But final ratification of this agreement will be a challenge. France and Poland, both of which have strong farming lobbies, are bitterly fighting the deal, infuriating Germany and the rest of the V4 who hope the deal could offer some respite, especially for carmakers.

The bad-tempered spat reportedly has some member states questioning Brussels’ role as the collective trade negotiator, while doubt over the European Commission’s ability to deal with the capricious incoming US president only appears to be deepening.

Amid the widespread belief that, as during the first Trump administration, carveouts on tariffs will be available for those happy to kowtow, individual EU members states have already been rushing to try to get on his good side.

The V4 countries might also look at their own failure to update the post-Communist economic model developed in the early 1990s, whereby it serves as a cheap foreign investor workshop for bolting together machines to sell in Western markets.

But few are holding their breath for deep and longsighted reforms, especially with populist forces stalking the region.

“The V4 went all in on German cars, but the automakers fell asleep. The car of the future is not what they assumed it would be. They didn’t see the end of the internal combustion engine coming, leaving Chinese manufacturers of electric vehicles to overtake them. The V4 countries are victims of this, and it’s a very difficult situation for policymakers,” says Grieveson.

- Signals to watch in 2025

Poland’s EU presidency: From January 1, Poland assumed its six-month stint as president of the Council of the EU. Seeking EU unity on how to manage transatlantic relations, especially on trade and defence, with the new Trump administration will be an integral part of the security agenda facing Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, suggests Andrius Tursa of Teneo intelligence.

Team Trump: The president-elect has said Howard Lutnick, his proposed secretary of commerce, will lead the trade agenda. The Wall Street bigwig has shown some ambiguity over tariffs, but has noted European carmakers are a target. At his US Senate confirmation hearing on January 29, he said was on board with Trump’s plan to pursue across-the-board tariffs country by country to restore “reciprocity” to America’s trading relationships. “My way of thinking, and I discussed this with the president, is country by country, macro,” Lutnick told the US Senate confirmation hearing on how Trump should impose tariffs. At the time of writing, the absence of former Trump stalwart and trade hawk Robert Lighthizer from the administration is seen as free-trade positive.

Inauguration day: Trump warned the EU on February 3 it could be next to face tariffs, after he put 25 per cent levies on goods from Mexico and Canada along with an additional 10 per cent tax on imports from China. Trump told the BBC that tariffs on EU goods imported into the US could happen “pretty soon”.

German snap election: At the February 23 snap election, the right-wing CDU looks set to win office. It has pledged to raise investment and defence spending, which would help Berlin mend strained transatlantic ties and talk Trump out of a punishing tariff on US imports of German cars and other goods.

Fiscal budgets: How much cash can EU states find in order to raise defence spending in a bid to keep Trump sweet and ward off the threat of tariffs? Many European economies are labouring under large deficits and piles of debt.

Poland’s presidential election: In May, Poland’s nationalist-conservative forces are hoping that Trump’s return to the White House will boost their chances of keeping the presidency when term-limited Andrzej Duda leaves office. Should the ruling coalition’s candidate, Warsaw Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski, triumph, it would ease government efforts to make deals with the US president.

Mercosur ratification: Ratification of the EU-Mercosur trade deal is likely to be a long, tough process for Brussels, with France seeking to rally Poland and other sceptics to block the agreement. Kate Parker, principal economist of Europe at the Economist Intelligence Unit, expects Paris will fail, but even then, technical preparations mean she doesn’t expect the process can even start until mid-2025. “Best case,” she says, “it could be ratified in the second half of next year. But it could be 2026.”

Trump’s administration will seek bilateral deals in order to split off EU states, in what will be both a tactical and ideological approach. It will be up to the EU to resist.”

– Alberto Rizzi of the European Council on Foreign Relations

Czech parliamentary election in October: Bouyed by the cost-of-living crisis, the populist ANO party has held a strong lead in the polls for some time, while several anti-system parties are hoping they can cross the 5 per cent threshold and clinch a spot in a coalition government. An economic hit from any trade war with the US could help seal the deal, putting Andrej Babis – “the Czech Trump” – back in the prime minister’s office.

Polish monetary policy: Struggling to balance stubborn inflation with the needs of economic growth, the National Bank of Poland had been widely expected to cut its benchmark interest rate – at 5.75 per cent the third highest in the EU – but the central bank cast doubt on that in late 2024. A trade war could push policymakers back into easing mode.

Economic data: A close eye will be kept on the performance of exports, investment, labour markets and household consumption across the year to try to gauge the effects that any tariffs, or even just the ongoing threat, may have.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News