Few other countries in the past five years have experienced as great a shift in fortune as Azerbaijan. As recently as 2020, the small, oil- and natural-gas-rich country was mired in a decades-long conflict with neighboring Armenia and lacked full control of its territory. For years, the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh, a mountainous area with an ethnic Armenian population within Azerbaijan’s internationally recognized borders, had been governed by a self-declared authority backed by Armenia. The unresolved status of the conflict left Azerbaijan diplomatically constrained and limited outside engagement with the country. It also made the nation strategically dependent—particularly on Russia, which cast itself as the region’s indispensable arbiter and used the stalemate to keep Armenia reliant on its security guarantees while maintaining leverage over Azerbaijan.

Today, that situation has dramatically changed. Following successful wars in 2020 and 2023, Azerbaijan has finally reincorporated Nagorno-Karabakh as well as seven adjacent districts that had been occupied by Armenian forces since the early 1990s. It has also gained a decisive upper hand against Armenia. Meanwhile, distracted by the war in Ukraine, Russia has ceded much of its former regional influence to Azerbaijan; and with Moscow cut off from Western markets, Azerbaijan has risen in importance as a global energy supplier, including to Europe. At the same time, it has strengthened ties with both Turkey and Israel, expanded its diplomatic and economic footprint in Central Asia, and increased its presence in the Middle East—staking out broader regional ambitions. The Azerbaijani government also appears to have favorable relations with U.S. President Donald Trump, who has business ties to Baku, the country’s capital, going back to his first term.

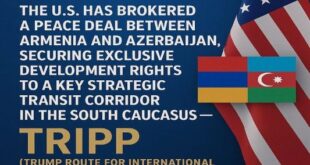

Amid this remarkable recent good fortune, Azerbaijan faces an important choice. After 36 months of negotiations, it now has a rare opportunity to reach a more lasting peace with Armenia. In mid-March, officials in Baku and in Yerevan, the Armenian capital, announced they had finalized the text of a long-awaited peace agreement. If formalized, the treaty would put a definitive end to the once intractable conflict, cementing a new order in the South Caucasus together with the region’s third country, Georgia. Yet it is unclear whether Azerbaijan will embrace the opportunity. Seeing itself in a position of strength, it has demanded further concessions from Armenia and appears to be in no hurry to conclude the deal. Meanwhile, although its oil- and gas-centered economy has brought much prosperity in recent years, these gains are fragile, and there has been little effort to diversify. Even a modest dip in energy prices—as has already begun to occur in 2025—could destabilize state finances and expose deeper vulnerabilities, including rising social inequality and public disaffection. In power for more than 20 years, Azerbaijan’s leader, Ilham Aliyev, has continued to tighten his political control and clamp down on dissent, relying on the country’s economic growth and a narrative of national strength to keep the population content.

These weaknesses, coupled with geopolitical uncertainty across the region, make Azerbaijan’s rise precarious. If the war in Ukraine begins to wind down, Russia might refocus on a region where it can still exert control—including over its former longtime ally, Armenia. Even short of that, Moscow could be a potent spoiler, especially if no peace agreement is signed and transport links between Armenia and Azerbaijan remain blocked. In such a scenario, the Kremlin could reimpose itself as the key guarantor of regional connectivity—on its own terms. And without a peace agreement, Azerbaijan could find itself economically exposed, politically overextended, and at risk of strategic stagnation. Lacking the broader dividends of peace, including foreign investment and regional economic integration, Azerbaijan might also lose the chance to build a more sustainable political order at home. As a result, the South Caucasus could remain trapped in rivalry, forfeiting what may be the region’s best opportunity yet for meaningful cooperation among its three states.

RUSSIA’S RETREAT

In one sense, it is remarkable that Azerbaijan and Armenia, decades-old antagonists, have hammered out a draft agreement at all. Without Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it is unlikely that a peace process would have even started. The story begins in 2020, when Azerbaijan won a decisive six-week war against Armenia, reclaiming most of the territory it had lost in the early 1990s. Fueling that triumph was advanced Israeli drone technology and an Azerbaijani military transformed by $40 billion in spending and decades of training, joint exercises, and coordination with Turkey. But just as Azerbaijani forces seemed set to retake the final Armenian-held areas of Nagorno-Karabakh, Russia intervened, halting the offensive and deploying peacekeepers on Azerbaijani soil. In Baku’s eyes, Moscow had snatched away its rightful victory. For Azerbaijan, like Armenia a former Soviet republic, the Russian military presence seemed to mark a return to the past.

Azerbaijan was now dependent on Russia, which exploited the situation for its own interests. Meanwhile, Armenia had effectively outsourced the security of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian population to Moscow, assuming that the Kremlin—a traditional Armenian ally—would never allow Baku to fully reassert sovereignty. By the eve of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin was pressing for a formal set of rules of engagement for its peacekeepers that would have allowed it to act as a de facto occupying force. Azerbaijan pushed back, and once Russia became mired in Ukraine, the issue quietly fell off the agenda. With the peacekeepers lacking a formal mandate or strong engagement from Moscow, an emboldened Azerbaijan began testing the Russian presence with limited military incursions and expanded forward positions in Armenian-populated areas.

Starting in early 2022, these moves steadily undermined Russia’s security guarantees, sending a clear message to the Armenian government and to Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenian population that the peacekeepers would no longer intervene to protect them. That message was confirmed in September 2023, when Azerbaijan launched a large-scale military operation that within a few hours captured all of Nagorno-Karabakh—without Russian resistance. Sensing it was overpowered, Armenia stood by, leaving Azerbaijan with a resounding victory and causing a mass exodus of Karabakh Armenians to Armenia—many of whom had long resisted integration into Azerbaijani rule.

Meanwhile, the Aliyev government had been leveraging geopolitical shifts to gain greater regional clout. Cut off from the West by sanctions, Moscow had begun relying on alternative trade routes—particularly the so-called North-South Transport Corridor, which runs from Moscow through Azerbaijan and Iran to Persian Gulf ports. Although the infrastructure on this route is still being developed, it has become a vital path for an isolated Russia and has strengthened Azerbaijan’s hand against the Kremlin. With Russia weakened, Azerbaijan has also deepened its strategic ties with Turkey. In the 2021 Shusha Declaration, the two countries expanded military cooperation and framed their alliance as a deterrent against outside interference. Moscow now understood that confronting Baku risked straining its complex and strategically important relationship with Turkey.

After the 2020 war, Russia had opposed a formal Armenian-Azerbaijani peace deal, sensing that it might weaken its own hand in the region. But after the invasion of Ukraine, the European Union, supported by Washington—which also helped mediate the process—initiated high-level direct talks between Baku and Yerevan and helped create a new negotiating framework. As a result of this push, in late 2022, Armenia formally recognized Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity—a step that had been almost unthinkable a year earlier. Baku, for its part, now positioned itself as a more autonomous actor, capable of engaging with Russia, Turkey, and the West on its own terms. By 2024, it was even able to compel Russian peacekeepers to withdraw ahead of schedule, thus clearing the way for a durable bilateral peace.

THE IRAN FACTOR

For Azerbaijan, however, peace with Armenia was only one of several opportunities opened up by the war in Ukraine. As Europe scrambled to reduce its dependence on Russian energy, Baku emerged as a partial alternative. Although Azerbaijani gas supplies could not rival the scale of Russian exports, they offered enough to buttress European energy security—particularly for southern European countries with more modest needs. Through the Southern Gas Corridor, which channels Azerbaijani gas to Europe via Georgia and Turkey, Baku solidified its role as a key energy partner, exporting more than 44 billion cubic meters of natural gas to the EU between 2021 and 2024.

Yet the profits were more modest than some in Baku may have anticipated. Despite higher global energy prices, gas exports brought in around $12 billion over those four years—less than Azerbaijan earned from oil in a single year, as surging prices delivered a much larger windfall. The outlook has been further clouded by Europe’s reluctance to expand its energy delivery infrastructure to receive more Azerbaijani gas exports—a step that some member states see as conflicting with the bloc’s ambitious climate goals.

At the same time, with the sanctions-induced collapse of traditional Europe-Asia trade routes through Russia, Azerbaijan had new economic opportunities. Russia turned to the South Caucasus as a critical link in alternative north-south trade routes, and Azerbaijan also capitalized on its position as a transit point for alternative east-west corridors—supported by Western efforts to reroute trade flows from Asia away from Russia via the Caspian Sea, in the so-called Middle Corridor. Although cargo volumes along this route have risen, they have been constrained by limited infrastructure and bottlenecks and still constitute just three to five percent of total Eurasian trade. Nonetheless, Central Asia’s growing economic importance—as a source of critical raw materials, energy diversification, and strategic balance vis-à-vis Russia and China—makes these routes worth developing. Even if the Middle Corridor never meets the lofty ambitions of its advocates, Azerbaijan’s strategic location ensures its continued relevance.

Yet this new geopolitical clout has not insulated Azerbaijan from regional tensions, especially with neighboring Iran. Although Azerbaijan is also a Shiite-majority country, Iran has watched its influence there steadily wane. The relationship worsened sharply after the 2020 war, which restored Azerbaijani control over a large stretch of its border with Iran and which tightened Baku’s ties to Tehran’s rivals, Turkey and Israel. An armed attack on Azerbaijan’s embassy in Tehran in early 2023—widely viewed in Baku as tolerated, if not orchestrated, by Iranian authorities—marked a low point in Azerbaijani-Iranian relations.

Although tensions have since eased, Iran is losing its long-standing leverage over Baku, including its historical relationship with Nakhichevan, the Azerbaijani exclave on Iran’s border. In March 2025, Turkey and Azerbaijan inaugurated a new gas pipeline connecting Nakhichevan to Turkey’s gas grid, and thus reduced Nakhichevan’s decades-old reliance on Iranian energy. If a peace agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia also unlocks a direct land corridor from Azerbaijan to the exclave through southern Armenia, Iran would lose yet another point of leverage. Such a shift would diminish Iran’s role not just in energy transit but also in regional trade, where it has long served as a conduit for Turkish goods headed to Central Asia. And it would further boost Turkey’s regional influence.

Iran also harbors deeper concerns about Azerbaijan: that in a future conflict over its nuclear program, Baku could serve as a springboard for Israeli military action. On top of that, Iran has its own restive population of some 20 million ethnic Azeris—making up perhaps as much as a quarter of the Iranian population. For this Iranian minority, many of whom are in the country’s northwest, a more assertive Baku, and its growing emphasis on shared ethnic and historical ties, could inspire ethnic mobilization, or even separatist aspirations.

THE BOTTOM OF THE WELL

Azerbaijan’s rising international profile has not insulated it from internal weaknesses. In the wake of the victory in Nagorno-Karabakh, President Aliyev has enjoyed greater popular legitimacy than at any previous moment in the country’s post-Soviet history. In theory, this should offer a rare chance for a broader political reset: for years, the lack of political and economic reforms and overinvestment in the military were justified by the unresolved conflict, and many Azerbaijanis hoped that victory would finally open up the country and allow it to fashion a new “post-Karabakh” national identity.

But those hopes are rapidly fading. Since 2023, the government has tightened its grip—jailing journalists, activists, and opposition figures while restricting access for foreign media and limiting the activities of several UN agencies and humanitarian organizations. In doing so, the government had continued to portray Armenia as a threat, drawing on the population’s shared experience of war, territorial loss, and mass displacement. But with the return of the occupied territories and little public appetite for renewed conflict, those experiences no longer resonate as they once did. The government shows little interest in moving beyond the old narrative—not only because it helps legitimize domestic control, but because no clear alternative national story has emerged. And as the government narrative weakens, the structural challenges it once helped obscure are becoming harder to ignore, including public frustration over limited economic opportunity and concerns about transparent governance.

Beneath the surface, economic vulnerabilities are mounting. Azerbaijan depends heavily on volatile revenues from its Caspian Sea oil and gas reserves. Oil output has plummeted from a 2010 peak of 823,000 barrels per day to just 566,000 by early 2025, as extraction has become more difficult. Developing new reserves could take years and require major foreign investment, a hard ask in a world transitioning toward renewables. Even this year’s moderate drop in oil prices—from around $80 a barrel in early 2025 to just $64 as of late May—could, if sustained, wipe out more than 20 percent of state revenue.

These structural risks complicate Azerbaijan’s wider ambitions. Baku’s geography alone will not be enough to make it a critical east-west energy and trade hub. Countries that have successfully leveraged their location—whether in Europe, the Gulf, or Central Asia—have paired it with institutional reliability, regulatory transparency, and a baseline of political stability. Foreign investors may not require democracy, but they do require rules-based systems—where decisions are predictable, institutions function consistently, and political interference and corruption is kept in check. Without them, no route—no matter how strategic—can fulfill its potential.

THE MISSING PEACE

The war in Ukraine has transformed Azerbaijan’s position in previously almost unimaginable ways. But these short-term gains do not guarantee lasting stability, and the government’s overconfidence in the country’s rise could backfire. Last December, for example, after a Russian missile mistakenly downed an Azerbaijani civilian aircraft, Aliyev himself publicly rebuked the Kremlin. Baku’s response—open and defiant—signaled a new attitude: it no longer fears Moscow as it once did. But that might change if Russia were to reassert itself in the Caucasus.

Similarly, Azerbaijani officials seem to assume that their country’s diplomatic proximity to Israel, and geographic proximity to Iran, will make Baku indispensable to long-term U.S. interests—regardless of who sits in the White House. The government had even signaled a preference for a second Trump administration, calculating that Trump would be tougher on Iran. Yet that alignment carries risks of its own. If tensions grow between Iran, Israel, and the United States, Tehran could lash out at Azerbaijan militarily or by using its influence with Shiite clerics to foment internal unrest—particularly if Baku appears to be supporting Israel.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan has stalled on a historic chance for lasting regional peace. In postponing the deal with Armenia, Baku has made two core demands: changes to the Armenian constitution to remove perceived territorial claims, and the granting of an uninterrupted land corridor connecting mainland Azerbaijan to the Nakhichevan exclave. Quietly, Azerbaijani officials suggest they may also insist on an upfront guarantee of major investment from the European Union and Western development institutions to help rebuild Azerbaijan’s formerly Armenian-controlled territories. Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding regions are now being gradually resettled by some of the more than 600,000 Azerbaijanis displaced during the 1990s war, but progress is slow; so far, only around 13,000 of them have returned. Many towns were heavily damaged, and nearly everything—from infrastructure to housing—has to be rebuilt from scratch amid ongoing demining efforts. But such Western investment may not come.

With creativity, patience, and trust, many of these issues can be resolved. Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan is a strong supporter of a deal, and if he manages to persuade Armenians that constitutional reform is simply a bilateral confidence-building step that will bring much larger long-term economic rewards, he might ultimately succeed. But if he takes such a controversial step before crucial Armenian parliamentary elections in 2026, domestic critics may accuse him of selling out, and the entire peace process could be derailed. Notably, Pashinyan is the only major political figure in Yerevan pushing for a permanent settlement, and members of Armenia’s opposition have called the proposed constitutional reform a betrayal of national interests. If Pashinyan loses power, it could open the door to a very different Armenian leadership, likely led by a mix of revanchist and Russia-leaning figures who may see renewed confrontation with Azerbaijan as politically advantageous.

Moreover, for many Armenians, the issue of reopening trade routes and borders—some of them closed for over three decades—remains politically charged, particularly the proposed route linking Azerbaijan to Nakhichevan. Here, the European Union, which is still seen as a credible peace broker on both sides, could propose practical arrangements that meet both sides’ expectations on access and control—while also offering financial assistance, infrastructure investment, and technical support to help implement them. Europe stands to benefit, too: a successful deal could help shift the geopolitical balance in the South Caucasus permanently away from Russia.

Turkey’s role will also be critical. Ankara sees the South Caucasus as part of its strategic hinterland and views normalization with Armenia as a way to help shape, not dominate, the postconflict order. It has deferred to Baku at every step, saying it will open its border with Armenia only with Azerbaijani consent. A peace deal would give Ankara the green light—and help develop a new regional order in which Turkish engagement, backed by EU diplomacy, could offer Armenia a strategic lifeline and limit any Russian return. A stronger regional role for Turkey will also help Azerbaijan, which ultimately relies on Turkey to counterbalance any renewed Russian pressure. The question is not whether a peace treaty is desirable but whether it can be secured before the window that has made it possible closes.

The longer a settlement is delayed, the more vulnerable the process will become to shifting political currents and external interference. Armenia’s domestic fragility, waning global attention, and renewed Russian interest could derail the positive steps made over the past three years. The strategic opening created by Moscow’s distraction in Ukraine will not last indefinitely. If further geopolitical shifts occur without a durable settlement in place, Russia may still find ways to reinsert itself—maybe not to restore its former dominance but to obstruct progress, prolong ambiguity, and make sure its interests are preserved. That outcome would benefit none of those who would be immediately affected by Russia’s presence—not Azerbaijan, not Armenia, and not the broader region.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News