On March 12, employees of Ukrainian House (Ukrainski Dom), the main NGO representing Ukrainians in Poland, received a bizarre email. The municipality of Bydgoszcz, in northern Poland, was writing back about Ukrainian House’s “formal request” to organise an election rally in favour of Rafal Trzaskowski, the presidential candidate of the liberal camp, on March 22.

Except that Ukrainian House never sent such a request.

“We are very political in the broad sense of the term when it comes to the rights of the Ukrainian community here or of migrants in general,” Oleksandr Pestrykov from Ukrainian House told BIRN in an interview. “But we never get involved in the fight for power in Poland. We never take part in electoral events or publicly express a preference in elections in Poland. That’s why we were extremely surprised [by the email].”

Pestrykov and his colleagues contacted Bydgoszcz municipality to clarify the matter. In the meantime, either on their own initiative or following enquiries by Ukrainian House, other Polish cities got in touch after receiving similar requests allegedly from the NGO: Gliwice, Czestochowa, Poznan and Rzeszow.

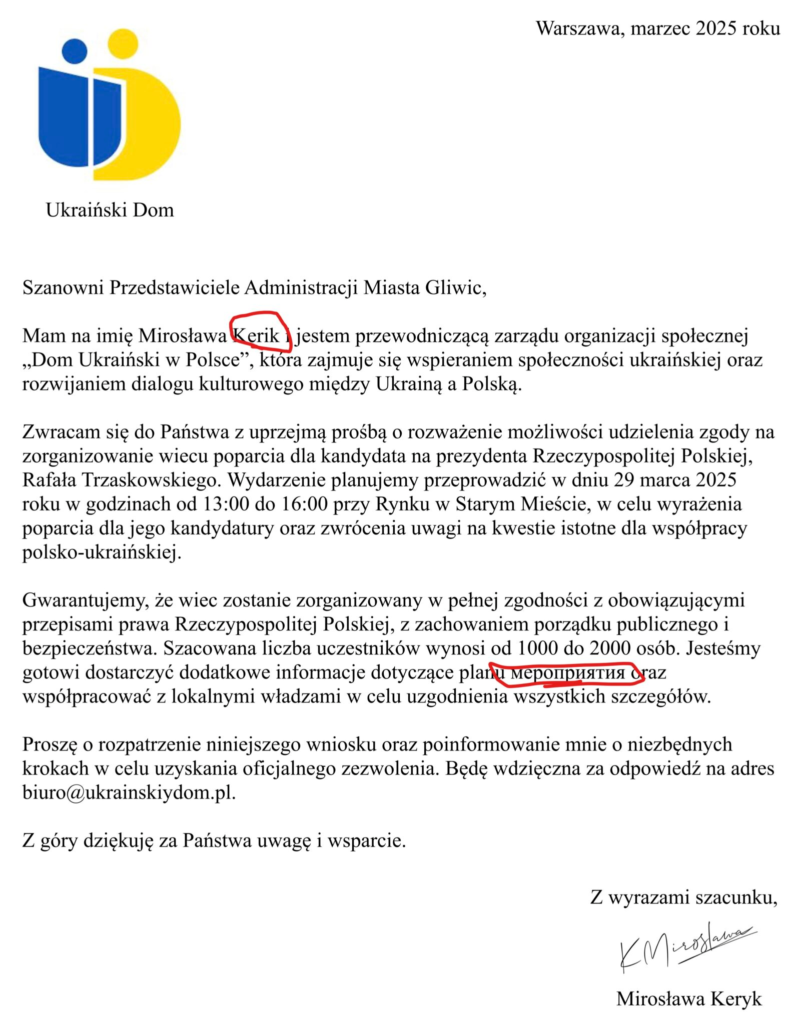

The requests were sent from a fake email address that was very similar to the official one of the organisation: [email protected] instead of the correct [email protected]. The text of the requests, shared with BIRN, contained several mistakes, for example a misspelling of the name of the head of Ukrainian House. The request addressed to the Gliwice municipality, although written in Polish like all the others, also included an isolated Russian word, its Cyrillic spelling standing out among the Latin letters of the other Polish words: мероприятие, meaning “event”.

Copy of fake letter from Ukrainian House making ‘formal request’ to organise an election rally in favour of Rafal Trzaskowski, the presidential candidate of the PO camp, on March 22 in Bydgoszcz, Poland.

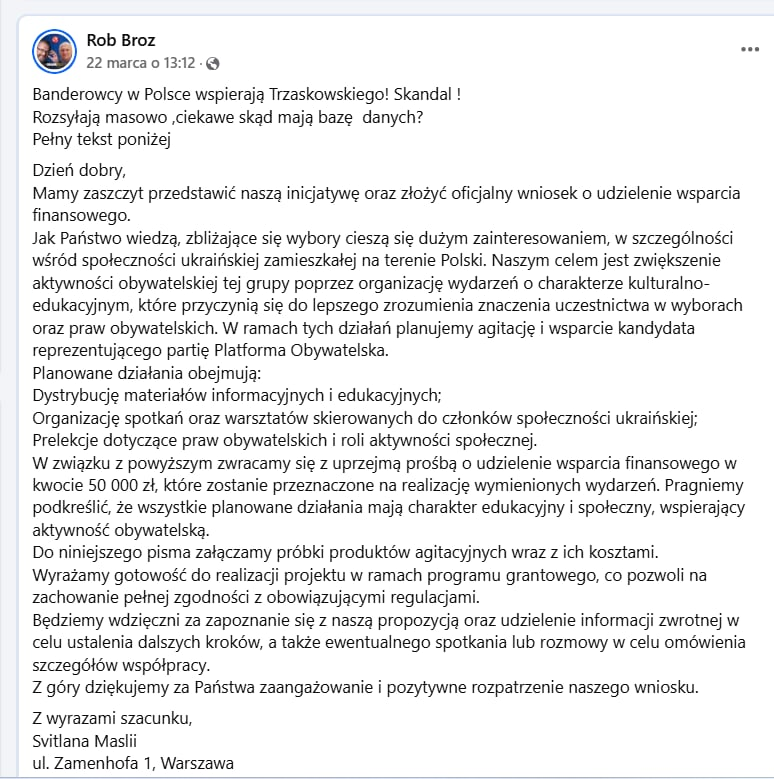

Less than two weeks later, a beneficiary of Ukrainian House’s services sent to its main office screenshots of a social media post by Rob Broz, apparently a local activist within the circle of the far-right presidential candidate Grzegorz Braun, which quotes from letters that an employee of Ukrainian House supposedly sent to business representatives across Poland asking for donations so the NGO could organise election rallies for Trzaskowski.

“The Banderites in Poland are supporting Trzaskowski! Scandal!” Broz wrote in a Facebook post, a screenshot of which was seen by BIRN. “Banderite” is a pejorative term used to describe followers of Stepan Bandera, a Ukrainian ultranationalist leader whose faction of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B) was involved in violent actions during World War II, including participation in atrocities against Poles, Jews, and Roma.

The Facebook post was also shared on various local groups in the Podkarpacie region in eastern Poland, Pestrykov said.

Screenshot of a social media post by Rob Broz, a reputed local activist within the circle of the far-right presidential candidate Grzegorz Braun, which was subsequently ordered removed by NASK.

Pestrykov and his colleagues wrote to the police, Internal Security Service (ABW) and the prosecutor’s office, among others, informing them about the incidents. Broz’s social media posts were removed after an intervention by NASK, a state research institute tasked by the Polish government with fighting disinformation during the presidential election campaign. But the perpetrators of the fake letters have so far not been identified.

“It’s very hard to say with 100 per cent certainty who did it. We don’t know,” Pestrykov commented. “What we can see is that the texts of the requests to municipalities were written using Russian language structure, there is no doubt about that to us. They were probably originally conceived in Russian and later translated into Polish using the very advanced translation tools available out there.”

“We are worried that those actors pretended to be us, and thus risked spoiling our public image,” he continued. “But we also think this action was less about discrediting us and more about discrediting Trzaskowski. The mood is such in Poland nowadays that the perpetrators thought that in order to have a candidate lose a few percentage points, it’s enough to show he is a friend of Ukrainians. And this to us is very concerning.”

Polish PM Donald Tusk attends a special meeting at Maritime Operations Centre in Gdynia, northern Poland, 22 May 2025. Tusk held a special meeting with security agencies after a vessel belonging to Russia’s so-called ‘shadow fleet’ was detected carrying out a suspicious operation in the Baltic Sea on 21 May. EPA-EFE/Andrzej Jackowski

Polarising campaign topic

The emails surfaced in the middle of Poland’s presidential election campaign. It is no coincidence; since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Poland has welcomed over 2 million refugees from Ukraine and the issue has quickly become one of the main topics discussed by the candidates.

Far-right candidates such as the aforementioned Braun and Slawomir Mentzen of the Confederation (Konfederacja) party, who in the first round came third with almost 15 per cent of the vote, have been fuelling anti-Ukrainian rhetoric for months, calling for a cut to all benefits for people from Ukraine and opposing the country’s accession to the EU or NATO.

Karol Nawrocki – the Law and Justice-backed candidate who is up against Trzaskowski in the second round of the election on Sunday – has echoed this rhetoric. Even Trzaskowski, who is from the liberal wing of Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s Civic Platform, has indulged in it to a degree, suggesting limiting the number of Ukrainian families that receive the well-known 800+ child subsidy.

Such divisive, sensitive topics in a society are precisely the kind of fertile soil Russia views as ideal for sowing the seeds of its disinformation campaigns. The Polish authorities have been keeping an eye out for Russian attempts to influence the presidential election, claiming to have neutralised numerous attempts so far. Yet experts interviewed by BIRN note that the usually obvious AI-generated deep-fakes or bot armies have been largely absent from this campaign. Instead, Russia appears to have turned to more subtle tactics, including scams like the one involving the Ukrainian House doppelganger.

“What is done on a large scale is scamming using the public images of politicians. There are many social media accounts active that pretend to be the official ones of the candidates – exactly as we’ve seen in Romania,” said Agnieszka Lipinska from NASK, the national research agency responsible for monitoring the external influences on the election, referring to the annulment of December’s presidential election in Romania after Russian interference boosting the online campaign of outsider candidate Calin Georgescu was identified.

Lipinska told BIRN that NASK did not identify those attempts as part of a larger coordinated strategy by a foreign agent. “The goal is rather to confuse the voter through smaller scattered measures,” she explained.

“In this campaign, we have not dealt with any controversial AI deep fakes. The attempts to discredit the candidates are not as aggressive as it has been in the past,” Lipinska said.

She explained that despite the importance of this election, Poland has also managed to avoid situations such as the data leaks that affected the past campaigns of French President Emmanuel Macron or the 2020 US presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

Thanks to its diversified social media landscape, she said, Poland has also been spared a situation in which social media platforms’ algorithms become heavily influenced by foreign actors, leading to a fast and large-scale promotion of previously unknown and niche candidates, as was the case in the first round of Romania’s recent presidential election.

But the more covert disinformation tactics seen in Poland also make it harder to identify the source of the disinformation and influence operations.

“What we’ve learned from our experiences in Ukraine is that the Russians often use the tactic of grooming a local actor, which allows them to hide better,” said Anastasia Romaniuk, a cyber-analyst from the Ukrainian group OPORA, which studies Russian disinformation. “If they find someone locally whose views match the Russian narrative, then they invest in boosting this person’s profile, sometimes even building them up almost from scratch.”

“It can be very hard to prove direct Russian involvement,” Romaniuk explained during a webinar for Polish journalists and NGOs organised by Ukrainian House on May 14. “But if you look very carefully at the platforms of these local actors, you eventually find comments boosted by Russian bots or narratives that are spread across platforms with the use of inauthentic engagement.”

Romaniuk said it is crucial to understand what are the main polarising or “unresolved” issues in societies that might be targeted by Russians. In the Polish case, for example, this could be concerns by some citizens that the Polish state is spending too much money on supporting Ukrainian refugees.

“If there is a vulnerability already there, an issue on which people don’t trust politicians, or a major question that the public has that they are not getting the answer to, this could be the space where the Russians will intervene,” she noted.

This is confirmed by Dominika Kasprowicz, a researcher at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow and a member of the state commission set up to investigate Russian and Belarusian influence, who highlighted that because of volatile and high-risk international events such as the war in Ukraine, Poles are becoming prone to taking extreme emotional positions.

“Russian officials and state publications very clearly delineate the Kremlin’s strategic goals and main narrative axes,” she said, explaining that the state commission she is part of has identified them to be the lowering of positive sentiments towards migrants and refugees, especially those from Ukraine in the Polish context, the erosion of trust in NATO and the EU by presenting the former as untrustworthy and the latter as aiming to dominate Poland, as well as undermining citizens’ trust in state structures.

Polish Digital Affairs Minister Krzysztof Gawkowski speaks during the opening ceremony of the Defence24 Days defence industry conference at the PGE National Stadium in Warsaw, Poland, 06 May 2025. EPA-EFE/RADEK PIETRUSZKA

Poland’s election shield

During the current presidential campaign, Poland experienced “an unprecedented attempt by Russia to interfere in the Polish elections” through disinformation and attacks on critical infrastructure, the country’s digital affairs minister, Krzysztof Gawkowski, said at the opening of the Defence24 Days security conference in Warsaw on May 6.

He claimed that Russia’s foreign military intelligence agency (GRU) has “doubled its activity against Poland” compared to last year: as a result, “there is no other country in the structures of the European Union that faces similar threats.”

In order to counter such election threats, at the end of January, the Polish government presented its Election Protection Plan. Dubbed the “Electoral Umbrella”, the plan encompasses monitoring social media for disinformation, organising training for NGOs, journalists and election committees, and bolstering cyber-security.

The measures also involved the launching of diagnostic tools for citizens and companies, including domain security scanning and reporting on password leaks, as well as the maintenance and development of the Bezpieczne Wybory (Safe Elections) website providing information about the electoral process.

“We learned our lessons from the Romanian example, so we created the Electoral Umbrella,” Gawkowski said. “In Romania, they did nothing for many months. We have been cooperating with the State Electoral Commission, ABW, NASK and other services since the start of the campaign.”

“We’re doing everything so that Russia doesn’t steal our democracy, even if it will try to,” he added.

In conversation with BIRN, NASK also gave credit to the experiences drawn from the Romanian example as well as other recent elections where Russia has tried to interfere. “After the elections in Romania and Germany, we are in a slightly different situation. An EU-level Defence for Democracy package has been set up to help combat disinformation,” Lipinska pointed out, explaining that the measure increased cooperation with large social media platforms in combating harmful content.

Yet while the Polish ruling coalition regularly informs the public about the occurrence of cyber-security incidents, reports them to the social media platforms, and often mentions Moscow’s possible involvement, it rarely provides much detail.

“There are just a couple of incidents that were confirmed by our authorities as clear Russian disinformation,” Pawel Makowiec, a cyber-security analyst with conference organiser Defence 24 told BIRN. “But there might be hundreds or even thousands that are not talked about, because cyber-security is usually dealt with behind closed doors.”

When asked whether Russian disinformation was a significant and strong factor in the Polish presidential election campaign, Makowiec replied: “It’s really hard to say, because in our domestic politics all sides are accusing their opponents of being Russian agents.”

The expert said that while there are many incidents known to the public in which Russians are suspected, Polish authorities could do a better job at presenting some of the evidence to the public.

One example he highlighted would be the cyber-attack against the IT system of the ruling Civic Platform party announced in April by the government.

“There was a cyber-attack on IT systems, specifically on the computers of both Civic Platform office employees and the election staff,” the head of the Prime Minister’s Chancellery, Jan Grabiec, said on April 2. “The attack consisted of an attempt to take control of these computers, to monitor all content from the outside, or possibly generate content via these computers.”

“A cyber-attack on Civic Platform’s IT system,” Prime Minister Tusk wrote on social media the same day. “Foreign interference in the elections has started. The security services point to an eastern footprint.”

The government never changed its line on this incident, that it was the Russians and Belarusians behind the attack, although limited information was shared with the public about the evidence.

“In the case of cyber-attacks, we may just trust our government when they say that they linked a specific website to Russian or Belarusian actors or that it was Russians who are behind this cyber-attack,” Makowiec commented. “But in the case of physical attacks on infrastructure, it might be useful to present more facts to the public. The police or prosecutors can always argue that they don’t say anything because that’s in the best interest of solving the case, but in a landscape where so many accusations of Russian interference are flying around, it might be useful to present some evidence that enforces what politicians say.”

So far, experts are positively evaluating the effectiveness of the Electoral Umbrella introduced by the government, but warn that the fight against foreign influence in Poland is far from over.

“It is important that this type of monitoring becomes not just a project but an integral element of the country’s security system,” added Kasprowicz. She also noted that while NASK has been successful in identifying and reporting threats, its duties and functions tend to shift depending on the government in power, making its findings of previous years of limited comparative value.

For Lipinska, “The incidents are being identified and reported, there is an increased awareness that something could happen, there is increased discipline among journalists.” But when asked about the worst-case scenario, she also remained cautious: “Let’s say it’s an umbrella for this kind of drizzle that we’ve been experiencing for now. We’ll see how it does if it starts coming down in buckets.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News