Russia introduced new regulations for foreign citizens in the country on February 5, and started keeping a list at the Interior Ministry of foreigners who are living or staying in Russia without proper documentation, the “controlled persons registry.” The rules are aimed at migrant laborers working in Russia, many of whom come from Central Asian countries.

Russia has set a September 10 deadline for foreigners in the country to clear up all their paperwork with the authorities or face expulsion with a ban on re-entry. Judging by recent comments from Kyrgyzstan’s ambassador to Russia, Kubanychbek Bokontayev, many might not make that September 10 deadline.

Needed but Not Desired

Over the course of the last two decades, millions of citizens from Central Asian countries have worked in Russia. Most are from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

The remittances they send home have grown to the point where this money now accounts for nearly 40% of the GDP in Tajikistan, 24% in Kyrgyzstan, and 14% in Uzbekistan. Most of these remittances come from Russia.

Russia badly needs the extra workers, and, until recently, the arrangement seemed to suit all parties. But the March 2024 terrorist attack on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall changed the situation.

The Russian authorities detained and charged a group of Tajik nationals for the attack, and the always simmering xenophobia in Russia, particularly toward Central Asians, boiled over.

New rules and restrictions have been imposed on migrant workers.

Those that came into force in February this year were only the latest in a series of changes that already included mandatory fingerprinting and photographs upon entry to Russia, a reduction in the term of stay from 180 to 90 days, and an increasing list of infractions that provide grounds for deportation.

In 2024, Russia expelled some 157,000 migrants who were in the country illegally, which, according to Russian Interior Minister Vladimir Kolokoltsev, was an increase of some 50% over 2023.

The Clock Is Ticking

At the start of February, just before the latest regulations came into effect, Russia’s Deputy Interior Minister Aleksandr Gorovoi said there were some 670,000 foreigners living illegally in Russia. Gorovoi added that more than half were women and children, “those who entered, but we do not see that they received a patent registered with the migration service… [or] that an employment agreement was concluded with them.”

On July 24, Kyrgyz media outlet AKIpress published an interview with the Kyrgyz Ambassador to Russia, Bokontayev, in which he said that at the start of July, there were some 113,000 Kyrgyz citizens on the controlled persons registry, which he referred to as the “gray list.” He also said there were some 80,000 Kyrgyz citizens on the “black list” of people barred from entering Russia.

In a separate interview with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Kyrgyz Service published on July 25, Kyrgyzstan’s General Consul in Russia, Bakyt Asanaliyev, said that about 30% of the Kyrgyz citizens on the gray list are children. Ambassador Bokontayev said Kyrgyzstan’s embassy is working to make sure those currently on the gray list do not end up on the black list.

Citizens on the gray list have additional restrictions placed upon them until they clear up their status. Among these are prohibitions on driving, marrying, traveling within Russia, changing their place of residency, opening a bank account, or spending more than 30,000 rubles (about $351) per month from existing Russian bank accounts.

Bokontayev noted that from February to the end of April, only some 4,000 Kyrgyz citizens on the gray list had legalized their status, and by the start of July, the figure was more than 7,000.

The pace could be quickening.

Asanaliyev said the number dropped from 113,000 at the start of July to 103,000 a little more than three weeks into July, though Bokontayev pointed out that it is difficult to give exact numbers as Russia’s Interior Ministry updates the controlled persons registry every six hours. Those who have successfully completed their registration are removed, while those recently caught without all the necessary documents are added.

With only some 17,000 Kyrgyz citizens having made themselves legal in Russia since February, it seems unlikely that all the remaining Kyrgyz citizens on the gray list will clear up their living or working status by September 10. Bokontayev noted there are long lines at Russia’s facilities for registering migrants, and the process of filling out paperwork and other requirements is time-consuming.

Easier for the Kyrgyz Than Others

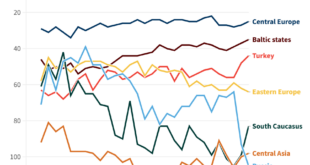

The number of Central Asian migrant laborers has been declining in recent years due to tightening restrictions, increased xenophobia, and the fear, among males, of being pressured or forced into joining the Russian military and sent to fight in Ukraine.

In May 2023, Kyrgyzstan’s Labor Ministry reported that the number of Kyrgyz citizens working as migrant laborers in 2022 was more than 1.5 million, of which 1.063 million were in Russia.

In January 2025, Kyrgyzstan’s Foreign Ministry said the number of Kyrgyz citizens living and working in Russia dropped to some 650,000 in 2023 and to some 350,000 in 2024. Ambassador Bokontayev cited figures from Russia’s Interior Ministry that showed the number of Kyrgyz citizens in Russia in the first quarter of 2025 was some 352,000.

Kyrgyzstan is a member of the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), a group that also includes Armenia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. As an EAEU member, Kyrgyzstan’s citizens, including migrant laborers, are given easier access to other member countries and enjoy social benefits, such as healthcare, not given to people from non-member countries.

Citizens from Tajikistan and Uzbekistan staying or working in Russia face greater challenges than Kyrgyz in entering Russia and obtaining all the needed official approvals. There are far more Tajik and Uzbek migrant laborers in Russia than Kyrgyz. It is unclear how many Tajik and Uzbek citizens are on the gray list, but almost certainly it is more than Kyrgyz. If citizens from Kyrgyzstan, an EAEU member, are having such a hard time legally registering themselves in Russia, it is likely more difficult for Tajik and Uzbek citizens.

Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov visited Russia at the start of July and met with his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin. Japarov asked for Russian assistance in getting Kyrgyz citizens legally registered in Russia before September 10. The Tajik and Uzbek governments are likely also working with the Russian authorities to ensure as many of their citizens as possible meet the looming deadline.

The sudden return from Russia of even tens of thousands of Central Asian citizens to their home countries, where most would join the ranks of the unemployed, is not something the Central Asian leaders want to see. Such a scenario could spark social tensions.

Russia, too, would prefer to keep at least most of the migrant workforce, though Russian officials have already made it clear that they do not want wives and children accompanying Central Asian migrant laborers to Russia.

Some sort of compromise seems likely, but the Russian authorities might start mass expulsions after the deadline just to demonstrate that they are serious about having migrants in the country working and legally registered.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News