Beijing’s Ambivalence Is Limiting Its Role

The war in Ukraine continues to shape China’s foreign relations. When European leaders visited Beijing last week to discuss trade and security, the need to find a resolution to the war was one major reason why Chinese-European relations had reached an “inflection point,” according to Ursula von der Leyen, the European Commission president. For Europe, China’s close ties with Russia and perceived support for its war effort have overshadowed ties between China and Europe for more than three years. In Beijing, European Council President António Costa told his counterparts that China should “use its influence on Russia to respect the United Nations Charter and to bring an end of its war of aggression against Ukraine.”

Chinese leaders have made some efforts to help broker a long-term peace deal, but they have not been able to push the conflict closer to a resolution. Although many officials in China want the war to end, Beijing is unlikely to play a leading role in resolving the conflict and achieving a lasting peace in the region. There is no consensus among either Chinese scholars or the general public on how to understand the war—and therefore on how to respond. China’s close ties with Russia and its strategic culture have also made it difficult for Beijing to press Moscow to make any concessions that might favor Ukraine. The longer the war drags on, however, the harder it will become to resolve fundamental tensions between China and Europe.

DIVIDED AT HOME

Forty months into the war in Ukraine, members of China’s strategic community, including foreign policy and security officials, researchers, and pundits, still have differing views on who is at fault and how leaders in Beijing should respond. Chinese social media platforms have been ablaze with fierce debates between pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian voices.

For some policymakers and citizens, the war is a conflict between two sovereign states in which Russia has violated Ukraine’s territorial integrity. Given China’s own history of suffering foreign invasions, which has left an indelible mark on its collective memory, many Chinese leaders and citizens empathize with Ukraine. China’s diplomatic rhetoric emphasizes its commitment to national sovereignty and independence and its opposition to the use of force against other states—principles that align with the UN Charter and that reflect Ukraine’s position. Russia’s actions, then, go against international law that China claims to uphold. Moreover, since the Soviet Union’s dissolution, China has established positive relations with Ukraine. Ukraine has supplied vital technology to China, most notably jet engines, which has been a boon for China’s military and industrial development.

Others see the war as a continuation of the ongoing reorganization of the region after the end of the Cold War. Although the former Soviet republics are now independent states, the ties that bind them together trace back centuries. Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine are particularly close. The process of reconstructing these interconnected societies along newly drawn nation-state borders is much easier said than done—and has been difficult, painful, and often bloody.

For those who view the region in this light, the war in Ukraine is also part of a decades-long conflict in which Western countries have ignored Russia’s underlying grievances and concerns. Much like how the Allied treatment of Germany after World War I sowed the seeds of World War II, continuous Western encroachment into Russia’s traditional geopolitical space after the Cold War stoked Russian anxieties about encirclement. Once the region achieved relative stability following the Soviet collapse, it became inevitable that Russia would seek to push back against perceived Western pressure.

The 1999 Kosovo war, in which Russian forces briefly seized Kosovo’s Pristina airport, was an early sign of Russia’s defiance toward NATO. So was the 2014 annexation of Crimea. The subsequent Minsk agreements stopped the fighting in eastern Ukraine for a time, but they could not solve the underlying dispute. Similarly, even if Russia and Ukraine agreed to put down their arms today, the long-term confrontation between Russia and the West would remain unresolved.

Many members of the public in China also empathize with Russia’s actions because they see China, too, as the target of Western encirclement and containment. Over the past few decades, particularly in the last ten years, the United States and Europe have ramped up pressure on China politically and economically. Most Chinese believe that the United States does not wish to see the rise of a strong China and is taking concrete steps to hold back China’s development. If anything, Chinese citizens often perceive Beijing’s diplomacy toward the West as overly restrained and cautious, and they feel a sense of vindication in Russia’s bold, even reckless, confrontation with the West.

China’s ambiguous stance on the war in Ukraine over the past three years reflects this internal division in Beijing. This isn’t just about disagreements from different camps of opinion; instead, most policymakers recognize both perspectives and do not want to fully embrace one at the expense of the other. The 12-point position paper on Ukraine issued by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs in February 2023 embodies this tension. The paper’s first principle emphasizes “respect for national sovereignty and territorial integrity,” a statement that supports Ukraine’s defense of its territory. China has also never recognized Russia’s annexation of Crimea nor its claims over four eastern and southern regions of Ukraine. The paper’s second principle, however, which states that the “legitimate security concerns of all countries must be taken seriously,” is a veiled show of support for Russia’s fears regarding Western pressure, including NATO expansion into what Moscow considers its backyard.

A COMPLICATED PARTNERSHIP

China did not choose this war, and Chinese leaders would likely prefer that it had never happened. Before the outbreak of the conflict in February 2022, China maintained friendly relations with Russia and with Ukraine. Throughout the war, China has continued to trade with both countries: many Western observers focus on China’s ties with Russia, but China continues to be Ukraine’s largest trading partner despite the disruptions caused by the war. Bilateral trade between China and Ukraine reached nearly $8 billion in 2024.

Although Beijing continues to seek areas of cooperation with Kyiv, Russia still occupies a far more important position in China’s overall foreign policy strategy. Russia is a major nuclear power and shares a land border with China that stretches more than 2,600 miles. Annual trade between China and Russia is worth nearly $250 billion. U.S. and European actions and rhetoric in the war have also pushed China and Russia closer. Western leaders often group China and Russia in the same camp, labeling them as part of an “axis,” such as an “axis of autocracies,” which has further sunk Chinese perceptions of Western countries and their governments.

But China’s position is hardly absolute. Although Western observers and politicians have seized on the idea of a “no limits partnership” between China and Russia based on Chinese leaders’ repeated use of the phrase, this idea overstates the complexity of Chinese-Russian relations. The phrase itself is more of a rhetorical flourish than a description of how Beijing sees Moscow. All foreign relations involve disagreements, differences, and potential conflict—and the bilateral ties between China and Russia are no exception.

China’s overall lean toward Russia obscures the challenges and contradictions in Beijing’s relationship with Moscow. Complying with Western financial sanctions has made it difficult to settle Chinese-Russian trade. Growth in bilateral trade between China and Russia stagnated in 2024 and declined by almost ten percent in the first half of 2025. And although Western countries have frequently criticized China over allegations that Chinese components have been used in Russian weapons, Ukraine has been extensively deploying Chinese-manufactured drones and using Chinese-made parts for its own drone production.

PROSPECTS FOR PEACE

Theoretically, China is well positioned to bring the countries to the negotiating table. China has taken an increasingly active role in mediating international conflicts in recent years, including negotiating a deal that restored ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and brokering peace between Russia and Ukraine would remove a major obstacle to improving China’s ties with Europe. Such a breakthrough could also steer the international order toward greater multipolarity and push back against the hardening binary divide between China and Russia on one side and the United States and Western countries on the other. If China were to succeed in bringing the war to an end, it would bolster its international image as a responsible world power.

The reality, however, is that China is unlikely to play a central role in resolving the conflict. Any role it would play would be secondary, at most, and limited to participation. If a multilateral peace process were to take shape, China would gladly take its place at the table if invited. But Russia and Ukraine are the direct parties to this war, and the United States and Europe are indirect participants through military aid. If the two primary belligerents—Russia and Ukraine—are unwilling to stop fighting, and if both remain wary of postwar cease-fire security guarantees, China will not succeed as a third-party mediator.

China’s geopolitical ties also constrain its ability to effectively mediate the conflict. China’s friendly relations with Russia limit its room to maneuver because Beijing is reluctant to pressure Moscow to make major concessions. China’s strategic culture shapes its diplomacy: when a country is broadly aligned with China, Beijing is hesitant to criticize that country’s specific policies—even if it privately disagrees. Western nations have repeatedly urged China to use its might to pressure other countries—including Iran, North Korea, and Sudan, along with Russia—but China usually rebuffs these appeals.

Meanwhile, China’s strained ties with the United States and Europe further limit its potential effectiveness as a mediator. Ukraine and Western countries may not want to see China lead peace talks even if it were willing to do so, likely because they believe China would push for a settlement favorable to Russia. If other parties brought an end to the war, Chinese leaders would then hope to contribute to peacekeeping and postwar reconstruction efforts. But China is unlikely to take the lead in bringing the parties to the table in the first place.

THE EUROPEAN CHALLENGE

To this day, and despite Beijing’s insistence that it wants to improve ties with European countries, the war in Ukraine remains the most significant irritant in relations between China and Europe. When the war broke out, China’s strategic community viewed it as a significant but distant conflict. It failed to grasp the full magnitude of the conflict’s impact on Europe—nor did it foresee how deeply the war would strain China’s relations with Europe as a result.

In 2019, the European Union introduced a strategy to view China as a systemic rival, competitor, and partner. But while rivalry and competition are easy, partnership has proved elusive. Beijing increasingly sees U.S. and European characterizations of China as toxic to better relations. China’s decision-makers thus have little interest in endorsing U.S. and European positions on the war and sacrificing its relationship with Russia even if doing so would help soothe tensions with Europe. From Beijing’s perspective, it is Europe that should correct its misperceptions about China’s role in this war—not China that needs to change its strategy.

Beijing is reluctant to pressure Moscow to make major concessions.

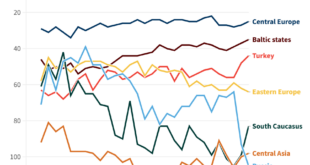

When the war eventually does end, how it is resolved will shape relations among the former Soviet republics and determine the future of Europe’s security architecture. If Russia emerges weakened, some countries in eastern Europe and the Caucasus may pivot further toward the European Union and Turkey, while Central Asian states could pursue more balanced foreign policies to hedge among China, Russia, and other regional players. Conversely, if the war ends in a manner favorable to Russia, Moscow’s grip over these regions may tighten.

These divergent outcomes will shape China’s strategy. What Beijing ultimately wants is a stable, open, and predictable regional environment that allows it to maintain friendly ties while expanding its trade and economic interests. Both possible future scenarios risk new tensions or even violent conflict in the region, which could strain countries’ relations with China and cause more headaches for Beijing. China’s strategists are debating how these postwar eventualities might unfold and how China can prepare itself for coming realignments.

China has tried to stay neutral or even passive in a war it neither anticipated nor welcomed. But this approach has not reduced tensions. Instead, and contrary to China’s wishes, the war has further entrenched great-power antagonisms among China, Russia, the United States, and Europe. No one has benefited from this outcome—least of all Ukraine. But until the war ends, it remains unlikely that anyone can reverse course.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News