Bottom Line Up Front

- Amid major setbacks for Iran and its Axis of Resistance, Iraq’s political leaders are trying to gain firm control over militias that are duly constituted forces but act outside the national chain of command.

- An armed clash at a government building between security forces and militia commanders in late July reflected their pushback against efforts to constrain their autonomy.

- Clashes and other forms of competition involving the militias will likely expand and intensify as the November 11 national elections approach.

- The outcome of Iraq’s debate over the militias might shape whether the country can integrate more closely into the Arab world and reduce Iranian influence in the country.

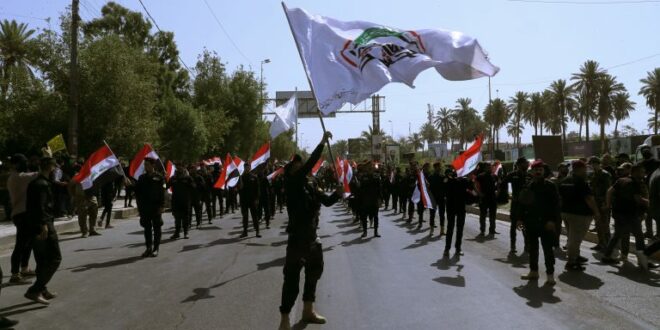

An armed clash at a government agricultural office in late July laid bare an escalating power struggle between Iraq’s national institutions, including the office of Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, and a parallel structure of militia groups, some of which often act independently and can challenge the Iraqi leadership. U.S. officials and global diplomats characterize the armed actors as Iran-aligned groups that act at the behest of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps – Quds Force (IRGC-QF), but close observers of Iraqi politics note that the armed actors have a deep social base and significant support among Iraq’s Shia majority population. That population fears that the official power structure is weak and corrupt, and perhaps poorly positioned to defend against Sunni Islamist extremists aligned with those who took over Iraq in 2014 and have come to power in neighboring Syria.

Despite the potential threat from Sunni extremists, the Sudani government, which moderate Shias dominate, is attempting to build a national consensus to disarm and demobilize armed factions outside direct government authority. Some of the militias maintain close relations with the IRGC-QF, and Sudani and other Iraqi leaders assessed that the country should not be drawn into the broader regional conflict between Iran and its Axis on the one side, and Israel and the U.S. on the other. Iran and its partners have suffered major setbacks at the hands of Israel and the U.S. that have damaged the economies and infrastructure in the countries in which Iran’s non-state allies operate. As in nearby Lebanon, the government is calibrating its actions to avoid a backlash from the militia commanders and their supporters. The outcome of the power struggle may determine Iraq’s regional alignment as Sudani seeks to integrate more closely into the Arab world and distance Iraq from Iran’s efforts to promote a region-wide “Axis of Resistance.”

The power struggle between Baghdad and the militias is also playing out as national elections approach on November 11, in which Sudani hopes to earn a second term. However, some Shia leaders who are part of a political alliance known as the Coordination Framework, which also includes Sudani, oppose a clear break with militias, viewing them as protectors against Sunni-led currents in Iraq and more broadly. The political considerations will likely compel Sudani to elicit a compromise with supporters of militia autonomy, heavily influencing Iraq’s trajectory toward greater state sovereignty.

As a symptom of the escalating power struggle between the government and the militias, in late July, clashes erupted in Baghdad’s Dora district between Iraqi security forces and members of Kataib Hezbollah (KH). KH is one armed group within the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), which are units recruited in 2014 to combat the Islamic State offensive that year and constituted as an official part of Iraq’s armed forces in 2016. Other PMF factions, such as Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba also have IRGC-QF ties and resist efforts to limit their autonomy. The incident reportedly was triggered by a dispute between KH and another unspecified armed group following the appointment of a new director at the Ministry of Agriculture’s office in Dora. At least 15 police officers were injured in the fighting, according to the Interior Ministry, and KH sustained some casualties. KH subsequently accused Sudani of orchestrating what it called a “malicious trap” by sending security forces to the agriculture office. Senior KH official Abu Ali Al-Askari posted a statement to Telegram accusing Sudani of sending a “massive army” to the office “not for security reasons…but out of frustration with the media of Kataib Hezbollah and the group’s positions on “major national and sovereign issues” – a reference to the Prime Minister’s stated policy of bringing all the country’s armed forces under central command.

Sudani used the agricultural office clash as an opportunity to build momentum for his push to rein in KH and other militia groups, judging that doing so would resonate with an Iraqi electorate that wants a more sovereign and independent Iraq, aligned with other Arab states, rather than a weakened Iran. Two weeks after the clash, Sudani ordered the removal of the commanders of the 45th and 46th PMF Brigades, with which the KH fighters who stormed the agriculture office are affiliated. His move was based on judicial findings of structural failings within the PMF, including the “presence of formations that act outside the chain of command.” In ordering the firing, Sudani assesses that he has backing for stronger state control from the marjaiyah – the top Shia religious authority. On July 17, Abdul Mahdi Al-Karbalai, the representative of Iraq’s undisputed top Shia religious leader (marja-e-taqlid), Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani, delivered a rare sermon urging an end to militia activity and the reinforcement of national institutions. This was seen as a clear nod from Sistani in favor of state sovereignty. If his firing of the 45th and 46th PMF Brigade commanders is implemented and not reversed, Sudani might be assessed as gaining momentum in his efforts to exert state sovereignty.

Sudani will calibrate his efforts to constrain the PMF militias to relieve pressure from Washington, which remains Iraq’s main benefactor and maintains more than 2,000 U.S. troops in the country. Since the 2003 U.S. invasion that ousted Saddam Hussein’s regime, U.S. officials have tended to formulate Iraq policy as a subset of policy toward Iran. During 2021-2023, KH and other militias attacked Iraqi bases housing U.S. troops 78 times in what U.S. officials perceived as an Iran-backed effort to compel the U.S. to withdraw its forces from Iraq. The U.S. retaliated for a few of those attacks that caused U.S. casualties. U.S. officials are exerting pressure on Sudani to disarm and demobilize KH and its allied militias — not merely constrain or marginalize them — as part of an effort to reintegrate Iraq into the Arab world and orient Baghdad away from Iran and its Axis of Resistance. The day after the agriculture office clash, the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad issued a statement explicitly blaming KH for the fighting and calling on the Iraqi government to bring those responsible to justice. U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio also reportedly warned Sudani that a proposed Iraqi law formalizing the PMF could entrench Iranian influence and legitimize groups Washington sees as destabilizing. That law is expected to be adopted nonetheless, backed by prominent political leaders who support the militias, such as former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki. Recognizing that Washington connects them with the IRGC, the PMF groups largely stayed on the sidelines as Israel and the U.S. struck Iran’s nuclear and missile facilities in June, perceiving that retaliation for the strikes on Iran would prompt major U.S. and/or Israeli counterstrikes.

U.S. officials have also sought to prevent the most extreme PMF groups as well as their regional partners from obtaining economic benefits from Iraq. Because the PMF are nominally part of Iraq’s security structure, Baghdad has been providing $3 billion for 2024 for PMF operations. However, U.S. officials have urged Iraqi officials to divert those funds to PMF units that report directly to the national command structure, rather than to KH and other militias closely affiliated with the IRGC-QF and operating independently. Earlier this year, the U.S. Treasury Department warned Iraqi leaders that the Iraqi state-controlled bank Rafidain must stop conducting business with the Iran-backed Houthi movement in Yemen. The U.S. requested that the Rafidain branch relocate to the Yemeni city of Aden, where the internationally recognized government of the Republic of Yemen is based. However, it is unclear whether the warning achieved the desired results. Iraqi Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein told his U.S. counterparts that the Iraqi government only conducts financial transactions with the Republic of Yemen Government, which maintains an embassy in Iraq. He also told U.S. officials, according to the text of an Iraqi memo, that: There is no possibility of the Houthis accessing the Iraqi financial system, and (Iraq) pledged to personally verify this matter.”

Some sources claim that Washington’s posture has had a tangible effect in diminishing coordination between the hardline PMF factions and other Iran-aligned groups in the region. Yet, at the same time, Iranian leaders are striving to counter Washington’s pressure on Baghdad to retain a measure of influence in Iraq. The commander of the IRGC’s Quds Force, Esmail Qaani, has visited Iraq at least three times in 2025, meeting with Sudani, Shia political leaders, and the heads of KH and other pro-Iranian armed factions, expressing Tehran’s opposition to any broad disarmament of the PMF groups. However, the weakening of Iran’s regional strategic posture over the past year, combined with the economic pressure exerted on Iran by U.S. President Donald Trump, leaves Tehran with far less leverage over Baghdad than it had in prior years.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News