Key Takeaways

SDF Collapse and Risks for the US Counter-ISIS Mission: The United States’ framework for sustaining success against the Islamic State in Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) in northeastern Syria is collapsing. The risk that fighting in the northeast will significantly imperil the US mission to combat ISIS remains high unless negotiations or Kurdish operations can slow the pace of government advance towards Kurdish-majority areas. The current conditions in northern Syria also risk fueling a Kurdish insurgency that will further create massive setbacks for the Global Coalition’s counter-ISIS campaign.

SDF Collapse and Risks for Communal Violence Against the Kurds: The Syrian government’s takeover risks facilitating serious communal violence against the Kurds, particularly as government forces enter Kurdish-majority areas. The Syrian government has deployed potentially problematic units into sensitive areas, possibly due to Shara’s decision to exploit the opportunity to take over certain SDF-held areas.

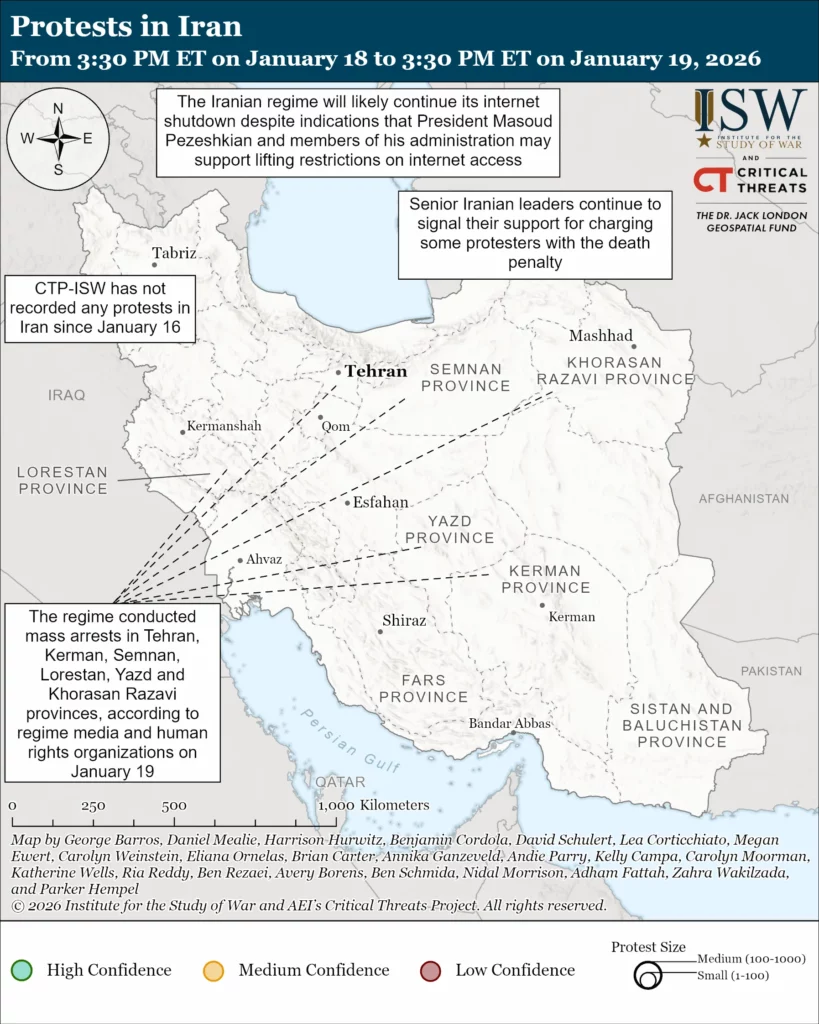

Iranian Regime’s Crackdown on Protesters: Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian, Parliament Speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, and Judiciary Chief Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei have rhetorically favored leniency toward protesters but continue to support the regime’s normal hardline approach to protesters, including executions.

Internet Shutdown in Iran: The regime will likely continue its internet shutdown despite indications that Pezeshkian and members of his administration may support lifting restrictions on the internet.

Toplines

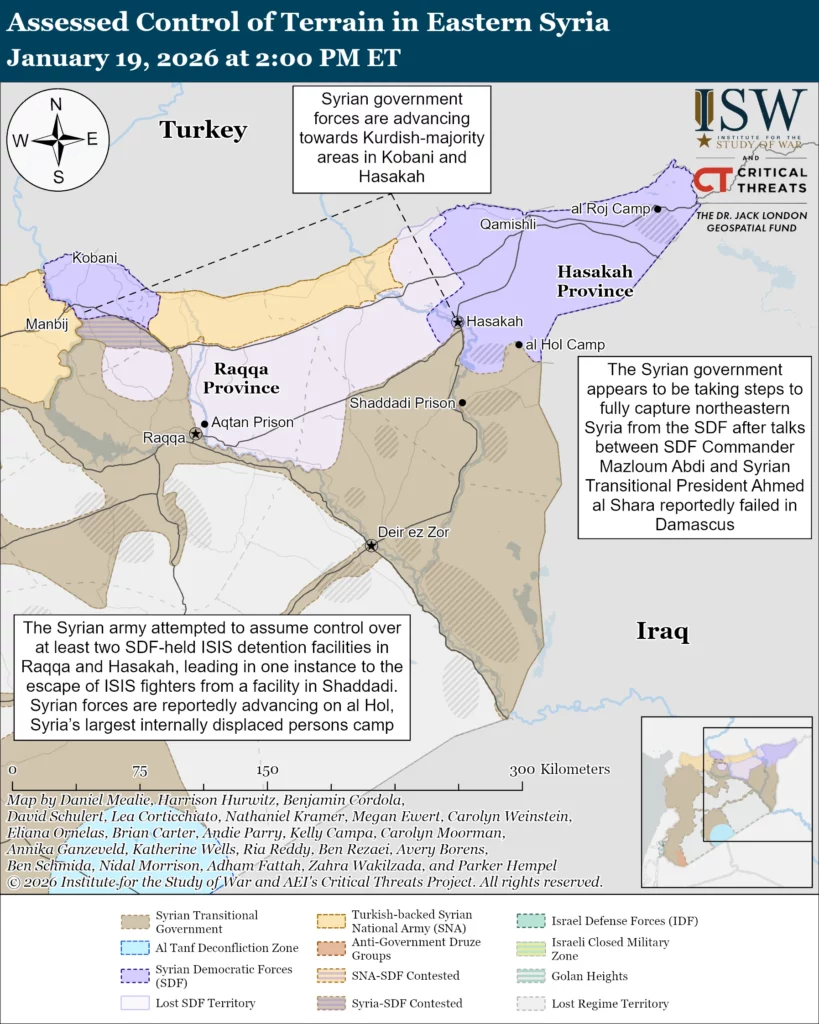

The United States’ framework for sustaining success against the Islamic State in Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) in northeastern Syria is collapsing. The Syrian government appears to be taking steps to fully take over northeastern Syria from the SDF after talks between SDF Commander Mazloum Abdi and Syrian Transitional President Ahmed al Shara in Damascus on January 19 reportedly failed.[1] Abdi and Shara met to presumably discuss and finalize the ceasefire agreement that they both signed on January 18 that outlined broad SDF concessions to Shara and his Damascus-based government.[2] Shara demanded during the January 19 meeting that the SDF hand over “the autonomous region” to the government, according to an SDF source.[3] Abdi left Damascus without any announcement or agreement.[4] Government forces—which have secured much of formerly SDF-controlled territory in northeastern Syria as of January 19—are advancing towards both of the remaining SDF-held regions of Syria: the Kurdish-majority areas around Kobani, northern Aleppo Province, to the west, and Hasakah City, Hasakah Province, to the east.[5] The SDF called upon Kurds in and outside of Syria to join the SDF to fight ”the Turkish state and its ISIS-minded gangs” shortly after Abdi returned to Hasakah.[6] The Syrian government contains many Islamist militia factions and some Salafi-jihadi groups, but it does not include organized ISIS fighters. Kurdish fighters are reportedly preparing to confront government forces in Kobani and Hasakah City, according to local media.[7]

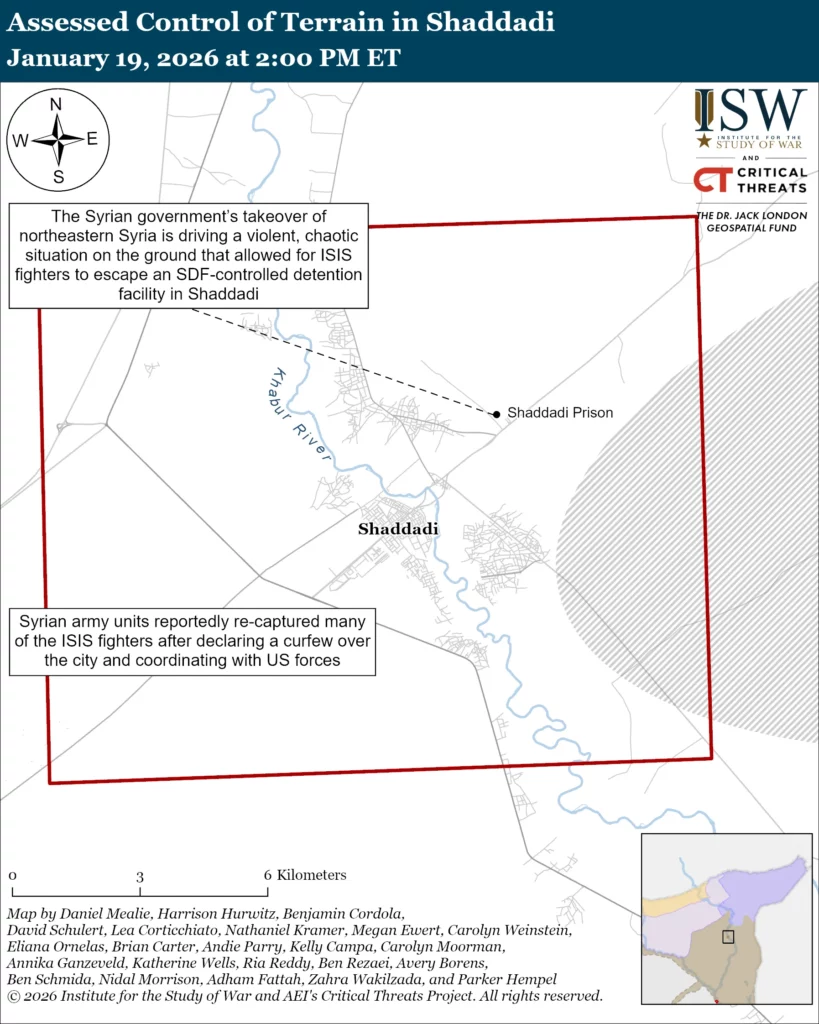

The Syrian government’s offensive in northeastern Syria is driving a violent, chaotic situation on the ground that has enabled ISIS fighters to escape prison facilities. The Syrian army attempted to assume control over at least two SDF-held ISIS detention facilities in Hasakah and Raqqa provinces on January 19 and engaged SDF units holding the centers.[8] Government-SDF fighting at Shaddadi Prison resulted in the release of over a hundred ISIS fighters into the area.[9] It is not clear how the fighters were released at this time, and the Syrian government and the SDF are trading accusations that the opposite side released the fighters.[10] Syrian army units reportedly recaptured the majority of the ISIS fighters after declaring a curfew over the city and coordinating with US forces.[11] Kurdish forces are similarly surrounded by and engaging with Syrian government forces at Aqtan Prison, an ISIS detention facility north of Raqqa City.[12] Syrian government forces are also advancing on the al Hol internally displaced persons camp—the largest in Syria with 10,000 Syrians and 6,000 third country nationals in it, many of whom are ISIS supporters.[13] ISIS detention facilities in northeastern Syria, which include but are not limited to Aqtan and Shadaddi prisons, hold an estimated 8,500 ISIS fighters in total.[14] A conflict that disrupts the containment of ISIS fighters and supporters in these facilities could release thousands of fighters into a violent, chaotic environment that may soon experience heavier SDF-government fighting.

The risk that fighting in the northeast will significantly imperil the US mission to combat ISIS remains high unless negotiations or Kurdish operations can slow the pace of government advance towards Kurdish-majority areas. A slowdown or halt of the government’s advance can keep abusive government forces out of Kurdish-majority areas and allow enough time for negotiations to stop the takeover or guarantee a more stable handover of SDF-held territory and infrastructure, including ISIS facilities.

Shara’s strategic objective to unite and consolidate his central government’s control over all of Syrian territory will likely drive him to prioritize operations to seize the remainder of northeastern Syria over assuming counter-ISIS responsibilities in newly seized areas of northeastern Syria, which imperils US strategic objectives to contain ISIS and prevent its resurgence. Shara has pursued negotiations with the Kurds for over a year to assert control over northeastern Syria.[15] The advance of Syrian forces towards Kobani and into Hasakah City on January 19 suggests that Shara sees a strategic window to impose state control over the remaining SDF-held areas in Kobani and Hasakah before Kurdish forces can organize a meaningful defense. Shara appears unlikely to order his forces to halt advances northwest and northeast in the absence of an agreement with Abdi that gives Damascus full control over northeastern Syria and without external involvement, given his long-held objectives.

Shara’s decision to seize a strategic window to further his own state centralization objectives in northern Syria caused the collapse of the SDF and a chaotic SDF withdrawal that has prevented an organized handover of SDF security responsibilities, including its counter-ISIS responsibilities. The SDF’s rapid withdrawal from Deir ez Zor led the SDF, including presumably counter-ISIS units, to abandon former positions throughout the province that were necessary assets for the SDF’s efforts to combat ISIS along the Euphrates River. Interior Ministry forces, which have deployed along the eastern Euphrates region to stabilize and secure the area, did not coordinate an effective or stable takeover of these positions as a result of the SDF’s rapid collapse.[16] Interior Ministry forces are the Syrian government’s primary counter-ISIS force. Serious coordination between the SDF and Interior Ministry forces, backfilling them, had it actually occurred, may have allowed the Syrian government to more effectively take over counter-ISIS operations in the region. Any future Syrian government operations, particularly in Kurdish-majority areas, may also invalidate any possible Syrian or SDF agreement to fold SDF counter-terrorism forces into Syrian state security services, as Shara and Abdi agreed in 2025.[17] It is unclear if either side will accept this proposal given the current circumstances.

The government’s takeover also risks facilitating serious communal violence against the Kurds, particularly as government forces enter Kurdish-majority areas. Both government forces and the SDF have accused the other of committing atrocities against civilians since the government entered Raqqa and Deir ez Zor provinces on January 18. Syrian media and an independent analyst have circulated reports that SDF fighters killed or injured over 100 people in tribal communities in Hasakah Province.[18] Others have alleged that Syrian army forces have conducted extrajudicial killings and other abuses against SDF fighters.[19] These reports create an environment that encourages reprisal-motivated violence, regardless of whether they are exaggerated or false. The cycles of retaliatory killings that took place along the Syrian coast in March 2025 and in Suwayda Province in July 2025 intensified rapidly.[20]

The Syrian government has also deployed potentially problematic units into sensitive areas, possibly due to Shara’s decision to exploit the opportunity to take over certain SDF-held areas. Shara would need to exploit this opportunity rapidly to be successful; the SDF’s collapse and the shock of the rapid government advance will be temporary, and it can reorganize if given the time to do so. The Syrian army’s 72nd Division, which consists of several pro-Turkish militias that fought in Turkish offensives targeting Kurdish forces during the Syrian civil war, advanced into Hasakah City on January 19.[21] The 72nd Division presumably advanced into Hasakah City because some of its units were based in the nearby Peace Spring region prior to the launch of the government offensive, but its deployment to a city with a large Kurdish population at any extremely sensitive moment raises serious concerns about the Syrian government’s commitment to preventing further communal violence. Kurdish leaders have cited the historic violence between various Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) groups and Syrian minorities as a factor that has deepened their fear and mistrust of the Syrian government. Most, if not all, SNA groups have been incorporated into government forces as of January 2026 and likely comprise some of the forces deployed to Kurdish-majority areas.[22]

The current conditions in northern Syria also risk fueling a Kurdish insurgency that will further create massive setbacks for the Global Coalition’s counter-ISIS campaign. The Syrian government’s rapid and forceful advance into northern Syria, and particularly Kurdish-majority areas, may facilitate a longer-term Kurdish insurgency, particularly if the government forcefully takes Kobani and Hasakah. The government’s rapid seizure of areas in Aleppo and Raqqa has probably led, at least partially, to the disorganization of SDF fighting forces across the Raqqa countryside, for example. The SDF, which a Syrian government map claimed is largely consolidated around Kobani and Hasakah, does not appear to be organized in Raqqa or Deir ez Zor in any meaningful way at this time.[23] There may be some SDF cells still operating in the Raqqa countryside and in areas in Hasakah Province that the government claims to have secured, however. Both are rural areas that contain a significant number of Kurdish-majority villages throughout the countryside that could render SDF fighters-turned-insurgents support. Kurdish insurgents could also rely upon existing networks with Kurdish-majority areas in northern Aleppo Province.

The government may prioritize combating a Kurdish insurgency, if it emerges, over an ISIS insurgency. Any longer-term insurgency in northern Syria would pull government resources from efforts to combat the growing threat of ISIS towards countering a burgeoning Kurdish insurgency, regardless of relative prioritization. A Kurdish insurgency would likely be more capable and supported by the population than ISIS in the short-term, and therefore more of a threat to the government. The government is more likely to prioritize the threat from the SDF because of the immediate threat it poses to Syrian unity in the short term. The SDF and its civil institutions governed Kurdish areas of Syria for nearly a decade, and it retains deep ties in the communities that will enable insurgents to access logistical support. The SDF is also better armed than ISIS, which has been relatively weak since 2019. The Syrian government has found multiple SDF-built VBIEDs in the last 24 hours, for example, while it and SDF forces find ISIS-built VBIEDS only very rarely.[24]

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian, Parliament Speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, and Judiciary Chief Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei have rhetorically favored leniency toward protesters but continue to support the regime’s normal hardline approach to protesters, including executions. Pezeshkian, Ghalibaf, and Ejei called for “Islamic compassion and leniency to those who were deceived and did not play a major role in terrorist incidents” in a joint statement on January 19.[25] This statement notably does not say that all protesters should be pardoned and continues to refer to protests as “terrorist incidents,” echoing the regime’s characterization of protesters as “seditionists” and “foreign-backed armed terrorists.”[26] The Judiciary announced that it will hand out sentences tantamount to moharabeh—enmity against God—that carry the charge of the death penalty for protesters deemed to be ”terrorists.”[27] The regime has historically responded to wide-scale anti-regime protests with mass arbitrary arrests, sentencing some protesters to death or life imprisonment while informally releasing others or freeing them through Khamenei’s pardons.[28] A US-based human rights organization reported that Iranian security forces have arrested at least 24,669 people as of January 19.[29] The regime cannot detain nearly 25,000 people and will almost certainly have to release thousands, issue life sentences, and execute others. Khamenei pardoned more than 22,000 detainees, and the Judiciary sentenced at least 25 protesters to death and executed at least seven protesters after the 2022 Mahsa Amini protests.[30] It is unsurprising that Pezeshkian, Ghalibaf, and Ejei signaled ”leniency” toward some protesters, since many would likely be released or pardoned under the regime’s standard crackdown policy. The joint statement signals support for the regime’s plans to execute some protesters by affirming the regime narrative that some protesters are responsible for terrorist acts. The regime has yet to publicly execute protesters from the January 2026 protests, but a human rights organization reported that regime jailers have committed lethal abuse at the detention centers.[31]

The regime will likely continue its internet shutdown despite indications that Pezeshkian and members of his administration may support lifting restrictions on the internet. Pezeshkian advised Supreme National Security Council Secretary Ali Larijani on January 18 to lift internet and communications restrictions to facilitate online business.[32] Science, Technology, and Knowledge-Based Economy Vice President Hossein Afshin stated on January 19 that internet access is expected to be restored ”today, tomorrow, or by the end of the week.”[33] Afshin added that authorities may grant fixed IP access to large companies if disruptions continue, but emphasized that this would not entirely address the challenges facing the digital economy.[34] The Pezeshkian administration may seek to restore internet access because it recognizes the economic toll that sustaining the internet shutdown has on the Iranian economy. Internet monitor NetBlocks estimates that country-wide internet shutdowns cost over $1.5 million USD per hour.[35] The shutdown, however, enables the regime to hide the extent of its brutal protest crackdown from its people and the international community. The regime has signaled that it continues to believe that the threat it faced from this protest wave has not passed and, therefore, may be reticent to significantly ease internet restrictions in the near future if it continues to fear renewed large-scale protests.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News