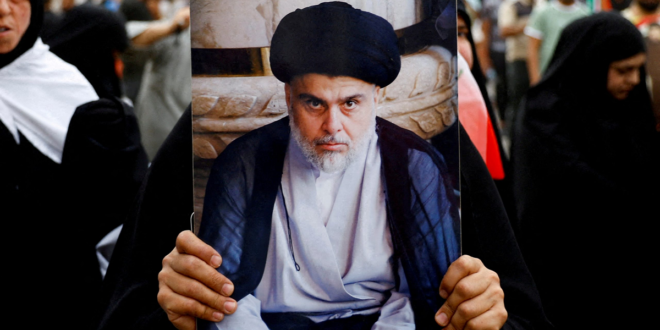

After eight months of stalemate in the Iraqi Council of Representatives (CoR), Muqtada al-Sadr ordered his parliamentary bloc to turn in their letters of resignation on June 12 and withdraw from the partially disabled legislature. Even with seventy-three members of parliament out (22 percent of the total members), the institution can still legally conduct regular business. If the mass resignation of the Sadrist bloc becomes final, the law will facilitate a smooth restoration of the full capacity by simply allowing the next highest performer in the October 10 elections to succeed resigning members from the same district. This is particularly straightforward, as the resignation of seventy-three members, although highly significant in symbolism, doesn’t preclude parliament’s ability to have a legal quorum.

Why did the Sadrists resign?

When his political bloc acquired the highest number of seats in the October 2021 elections, Sadr made his intention clear that he no longer was interested in the consociational government formation that prevailed in the past. He proposed a cross-sectarian “national majority” government, with an opposition in the CoR to monitor and check government performance. To this end, Sadr made a firm alliance with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which received a majority of Kurdish votes, and with the United Sunni Front, which was formed by merging the two major Sunni coalitions: Taqaddom and ‘Azm.

With a comfortable majority, this coalition—known as Inqath Watan—initially seemed unstoppable in forming a government and ruling Iraq, according to this new approach. However, a few setbacks ended this project before it had a chance to come into being. Having been unable to find a way to revive the “national majority” promise that Sadr placed his entire political weight behind, he had no choice but to keep trying with little hope of success, return to consociation, or withdraw his coalition from the government formation negotiations. He chose the least costly political option and ordered his followers to resign from the CoR.

Sadr’s allies overplayed their hand

From the outset, it was clear that Sadr’s allies didn’t share his vision of a “national majority” government, but were mostly interested in winning comfortably in a multi-level zero-sum game on his back. The KDP delivered the first blow to Sadr’s project by presenting a presidential candidate—former Finance Minister Hoshyar Zebari—with little hope of being appointed and insisting that he was their only candidate. Opponents of Sadr’s coalition went to the Iraqi Federal Supreme Court and easily excluded Zebari.

The Supreme Court found Zebari’s prior impeachment and duly removal from office by the CoR a sufficient reason to disqualify him. Furthermore, the KDP, taking advantage of their new strong coalition with Sadr, violated the traditional distribution of political positions that assigned the presidency to their Kurdish partners, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). This KDP encroachment pushed the PUK to join the Shia opposition and some Sunni and independent members of parliament—all amounting to more than one-third of CoR members. The last blow to the “national majority” proposal was dealt by the Supreme Court, which mandated the presence of a two-third majority of CoR members to achieve a quorum for electing the president. All the opposition needed to do was abstain from attending the election session to block the KDP candidate. Without electing a new president, parliament cannot proceed to form a new government. The project of Inqath Watan accomplished one-third of its internal deal—the election of Mohammad al-Halbousi as speaker—but not the other two top positions: president and prime minister.

The counter-argument to Sadr’s national majority government

The strongest argument against Sadr’s “national majority” government came from the Shia opposition, who objected to it on the basis that it was designed to exclude only the Shia from the consociation. They noted that the Kurds continue to have the presidency as an exclusive Kurdish choice while the speaker position also remains an exclusive Sunni choice. Additionally, the Kurds and Sunnis will have the right to select the prime minister—a Shia position—with the participation of a minority of the parliament’s Shia.

This situation would be particularly absurd, because, under the 2005 Iraqi constitution, Kurds and Sunnis don’t have the constitutional entitlement nor the required numbers to secure the positions allocated to them, much less the ability to dictate to the Shia who their prime minister candidate should be. While the Shia also have no constitutional entitlement, they do have the votes to unilaterally elect or block any candidate. Splitting the Shia vote in the CoR by exploiting their internal rivalries is an act of bad faith by the Sunni and the Kurdish leadership, according to the opposition voices who reject the “national majority” project. They insisted that the Shia constitute a majority in parliament and in society at large, and that, if they cannot govern on a winner-take-all rule, then at least they shouldn’t have other ethno-sectarian groups meddle in the one high-level leadership position that is assigned to them.

What direction will government formation take now?

The resignation of the entire winning bloc of parliament is a great challenge to the Iraqi political system. The Sadrists have a potent popular base that can challenge everyone else. The beneficiaries from such a resignation (when the new CoR members take the oath of office) will have to be careful in handling the aftermath and must maneuver carefully to fill the vacuum. They would be prudent to demonstrate genuine goodwill to the Sadrists and resist the temptation to exclude them from the power-sharing arrangement. After all, it was on the basis of their objection to Sadr that he attempted to exclude some Shia from his majority government project. They can reach out to the Sadrists by offering them cabinet positions commensurate to their weight in the CoR before their resignation.

If the Sadrists reject that, which is expected, an offer should be made to assign these cabinet posts to independents chosen with Sadrist input. If this is also rejected, then a reasonable course would be to either extend the current government’s term, granting it full authority to govern and a mandate to prepare for another snap election, or form a new government with the same mandate. Both latter solutions would require parliament’s consent to dissolve itself and pave the way for a new election (if the Sadrists are completely out of the government and the CoR, no government can last anyway).

That said, an early election won’t solve the Iraqi dilemma. No matter how many times the elections are repeated, parliament’s demographic and political configuration won’t change, as the seats are firmly allocated to demographically segregated districts, with only a few exceptions. For real political reform to happen, Iraqis must return to the drawing board and courageously correct their mistakes in the 2005 constitution.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News