This week, Russia struck deep into Ukraine and hit the capital, Kyiv, with kamikaze drones. These small and noisy airborne devices are designed to strike at a distance. They are nimble enough to avoid many air defense systems.

Unlike many other attack drones, they do not use weapons to destroy their targets. They are the weapon.

The kamikaze drones used by Russia are believed to be imported from Iran. They “are both military weapons and psychological weapons,” said Samuel Bendett, a Russian-military analyst at the Virginia-based research group CNA. “Attacks on major cities that are supposed to be well-defended against aerial threats demonstrate that Russia still has the capacity to inflict damage, whether military or civilian targets are struck.”

But drone attacks have already become a regular feature of the war in Ukraine, with both sides utilizing the deadly aircraft in different ways.

What are kamikaze drones?

The drones that Russia has been deploying, Ukrainian and U.S. officials say, are manufactured in Iran, where they are known as Shahed-136s. They are designed to strike specific targets with explosives that can be delivered at distances of up to 1,500 miles.

Russia has renamed the Shahed-136 as the Geran-2. Iran has denied giving Russia drones for its war against Ukraine.

The drones are part of a weapons category known as loitering munitions — meaning that they “are designed to loiter over battlefields,” looking for targets such as radars, Ingvild Bode, an associate professor of international relations at the Center for War Studies, a research group within the University of Southern Denmark, previously told The Washington Post. “When they have found the target, [they] launch themselves onto it.”

The “kamikaze” term is often applied to this and weapons such as the U.S.-made Switchblade drones in reference to the military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Japanese empire during World War II. Unlike those aircraft, these new weapons have no pilot onboard.

Ulrike Esther Franke, a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said that kamikaze drones have been used regularly in other conflicts, including in the recent wars between Azerbaijan and Armenia. In those conflicts, Azerbaijani troops used the Israeli-developed Harop drones, which are similar to Shahed-136s in size and capabilities.

However, the scale of use by Russia and the reports that it has bought an arsenal of thousands “makes this relatively unique,” Franke added.

Because of the distinctive buzzing sounds they make as they approach, the Shahed-136s are typically less destructive than precision missiles — civilians can see and hear them coming, so they have more time to seek shelter before any explosion. Some Ukrainians have dubbed them “flying mopeds” because of their loud engines.

Unlike large missiles, the drones have a blast radius that is smaller, and they don’t necessarily send shrapnel flying in every direction.

But they can also slip past Ukraine’s air defenses — or force the military to use its limited air defense resources to neutralize them before they can strike their target.

How is Russia using them?

Russian forces seeking an advantage on the battlefield have increasingly been making use of drones. U.S. and allied officials, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss security matters, have told The Post that Iran recently began delivering the drones and other weapons to Russia, sending technical advisers to train Russian forces in how to operate them. Pentagon officials have publicly confirmed the use of Iranian drones in Russian airstrikes.

Ukraine believes Russia has ordered as many as 2,400 kamikaze drones from Iran. In response, Kyiv has urged its allies to send sophisticated air defense systems.

Russia has its own arms industry, and to some experts it is notable that Moscow has to rely on Tehran for drones. “Turning to Iran in 2022 suggests that Moscow still has an inadequate domestic capability in drones,” Douglas Barrie of the International Institute for Strategic Studies wrote in one recent analysis.

But the attacks in Kyiv have shown the value in kamikaze drones, even if they are procured from abroad.

“Many in Russia were calling for mass strikes against Ukrainian infrastructure months ago to slow down the Ukrainian military’s progress,” Bendett said. “These cheap, expendable drones offer a simple solution.”

Franke, of the European Council on Foreign Relations, had a similar observation: “These systems allow Russia to terrorize Ukrainians at low costs, and far away from the front lines. While fighting these drones is not the most difficult task ever, it is difficult to do so everywhere at once.”

Russia has largely used kamikaze drones to attack military and infrastructure targets in southern Ukraine. Its forces first deployed the Shahed-136 in northeastern Ukraine in September, according to Britain’s Defense Ministry. In an intelligence update, the ministry argued that the use of the weapons near the front lines suggested “that Russia is attempting to use the system to conduct tactical strikes rather than against more strategic targets farther into Ukrainian territory.”

Since mid-September, Ukrainian forces have claimed they shot down Iranian-made drones in various parts of Ukraine. Speaking by video conference to Group of Seven leaders last week, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said, “Every 10 minutes I receive a message about the enemy’s use of Iranian Shaheds.”

This has led Kyiv to downgrade its diplomatic relations with Tehran. Zelensky called the partnership between Russia and Iran a “collaboration with evil,” while Tehran accused Kyiv of overreacting based on “unconfirmed reports” and “media hype by foreign parties.”

The drones were used for the first time to strike central Kyiv on Monday in what appeared to be an attempt to target a thermal power station that supplies the capital. At least four people were killed in the blasts, officials said. Mykhailo Podolyak, a senior adviser to Zelensky, accused Iran of being “responsible for the murders of Ukrainians.”

Drones over Ukraine: Death in different sizes

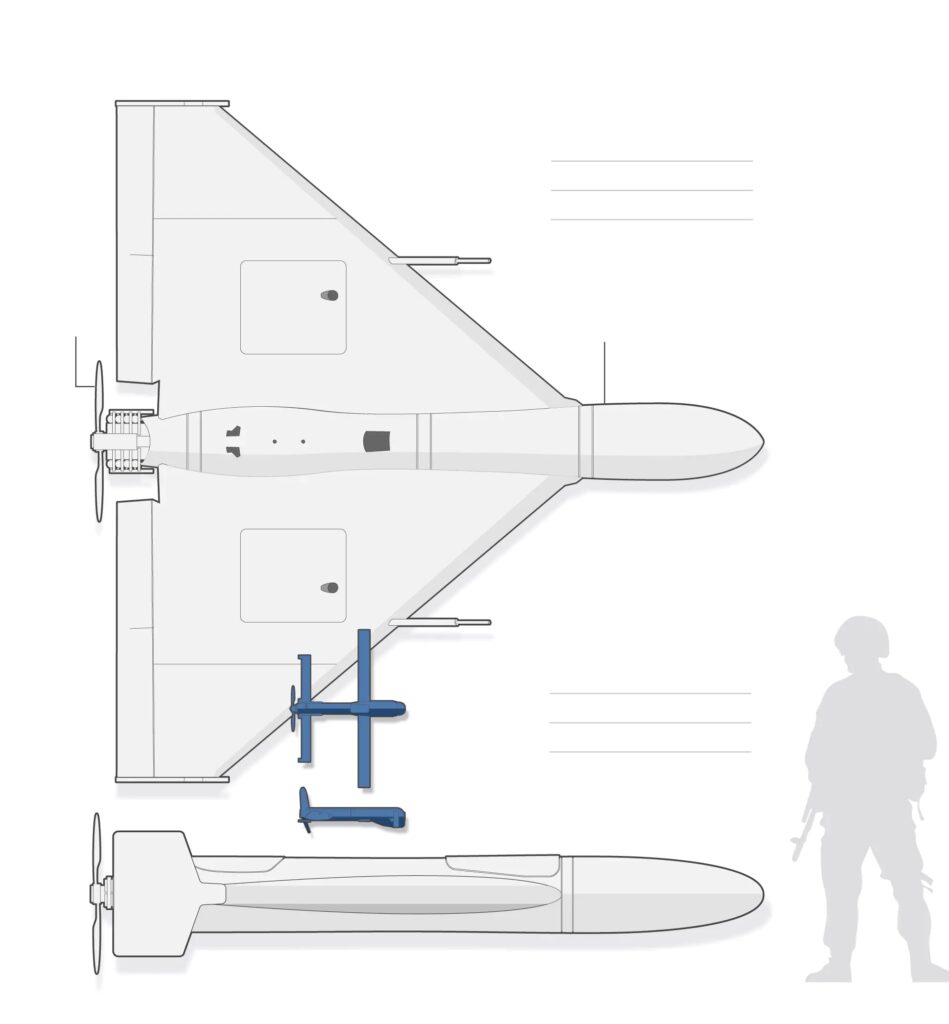

Iranian Shahed-136 drones can loiter over areas for hours until their cameras identify a target and the drone drops on it like a bomb.

The Russians are using these weapons to devastating effect without risk to their troops.

How is Ukraine using them?

The United States has pledged to send Ukraine more than 700 of its own kamikaze drones, called Switchblades, and trained some Ukrainian soldiers in April on how to use them.

With its thin body and ruler-shaped wings, the Switchblade 300 drone, the model in widespread use, is different in appearance from the Shahed-136, which looks like a miniature delta-winged fighter plane. But the idea behind the two weapons is similar: Allow a remote operator to take out a target with deadly efficiency and evade detection and air defense.

A key difference between the Shahed-136 and the Switchblade is range: Even the larger model of Switchblade has a maximum range of up to 25 miles, a fraction of that of Russia’s kamikaze drones.

The Switchblade 300, of which hundreds have been sent to Ukraine, can be deployed in the field, and packs less of a punch than larger drones but can be harder to shoot down. The United States is set to send 10 Switchblade 600s, a larger model, to Ukraine, Angela Schutt, a spokeswoman for AeroVironment, the company that makes them, confirmed in an email.

Ukraine also has been using the domestically developed RAM II kamikaze drones, which were partly paid for by crowdfunding. This drone also has a smaller range, going up to only 18 miles, and production has been hampered by supply issues.

Non-kamikaze drones have proved important for Ukraine, too. Ukraine also has deployed Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 drones and claims to have destroyed many Russian military targets with the aircraft’s laser-guided missile attack system. That drone is so popular in Ukraine that a Ukrainian soldier released a song in its honor.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News