The war in Ukraine has stoked inflation and increased the number of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion throughout Europe. With food and energy prices remaining high in 2023, experts expect more people to fall below the poverty line.

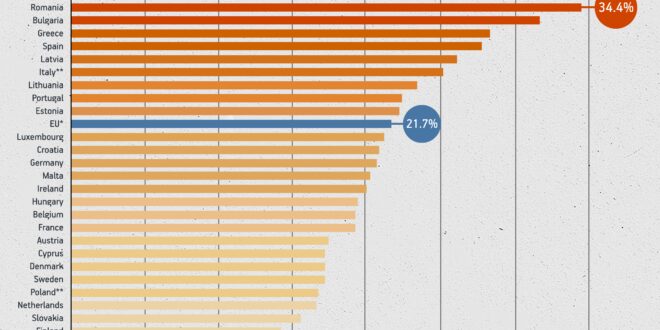

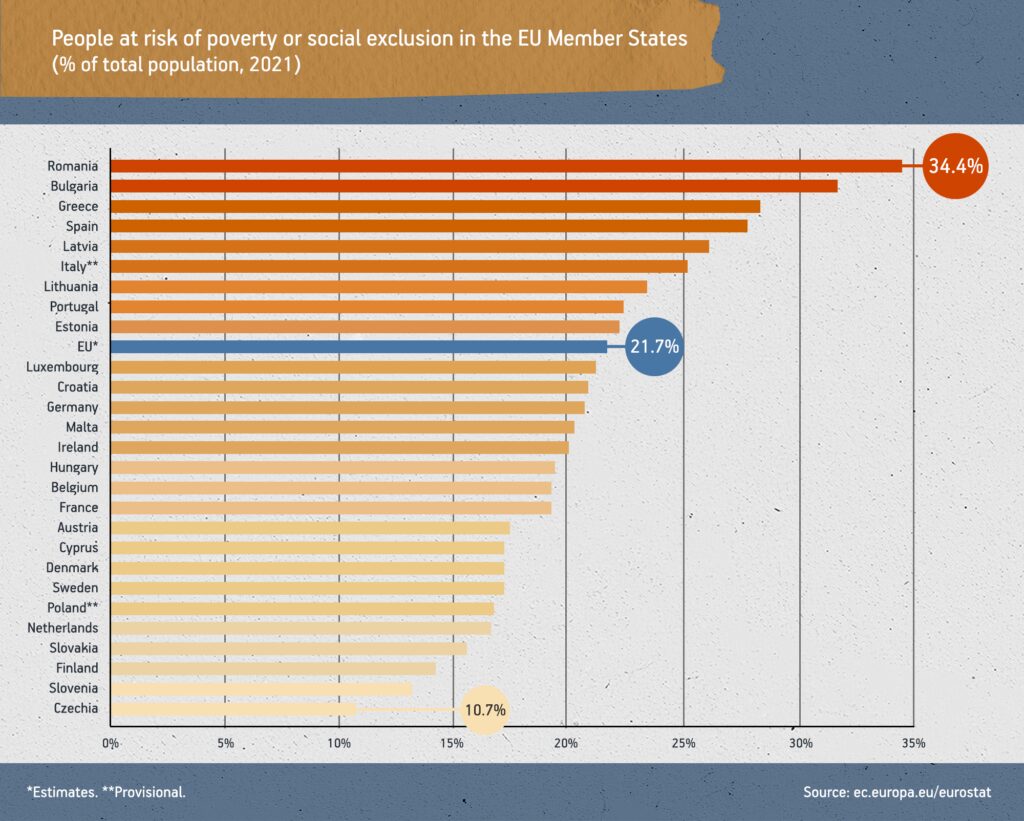

At the end of 2021, 95.4 million people in the EU were at risk of poverty or social exclusion, equivalent to 21.7 per cent of the EU population, Eurostat’s At Risk of Poverty or Exclusion (AROPE) index showed. More than 15 per cent of the populations of Hungary, Poland and Slovakia were at risk of poverty, while Czechia posted the lowest figure in the EU at 10.7 per cent.

That latest AROPE reading was released before the war in Ukraine began in February 2022, though bore out the European Commission’s predictions the previous year that COVID-19 would raise the percentage of EU citizens at risk of poverty or social exclusion from the 92.4 million people recorded in 2019 by anywhere between 1.7 and 4.8 percentage points (in actuality, it rose by 3.0 percentage points).

The war in Ukraine, with its attendant fall in economic growth, steep rise in inflation and resulting cost-of-living crisis, promises to raise the AROPE index even further in 2022 and 2023.

1.1 Overview

In 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, along with climate shocks around the world, have made any progress on poverty reduction “more challenging than ever”, the World Bank said. In July 2022, some 71 million people worldwide were reported to be experiencing poverty due to soaring food and energy prices driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) warned.

With EU-27 inflation reaching 11.1 per cent in November 2022 as a result of the war in Ukraine, Central European states are struggling not only with soaring prices, but also with being some of the most heavily dependent on the oil and gas supplies that Russia started limiting in 2022. This is feeding into civil discontent, which is being exploited by extremist forces. On September 3, 2022, around 70,000 people turned out at protests in Prague calling for the government to drop its support for Ukraine, quit the EU and NATO, and cosy up to Russia.

Call centre workers suffered mental breakdowns after listening to the stories of some of these people.

– Radek Habl, founder and director of the Institute for Debt Prevention and Resolution

Many Czech households are struggling to pay for their electricity and gas bills and a personal debt crisis is looming, as BIRN has reported. Some companies complain that their energy costs have risen by 2,000 per cent compared with a year ago. Concern is growing that the winter could see energy shortages, and the main question is just how deep a recession is on the way.

Poles, especially, been feeling the brunt of rising food and energy prices. In June, Poland’s inflation rate reached more than 15 per cent, one of the highest in Europe and a level not seen in this country since 1997.

In Hungary, annual inflation in 2022 has been even worse, reaching 22.5 per cent in November. Food prices in the country have risen on average by 43.8 per cent, with the price of some items like eggs more than doubling. In December 2022, inflation in Hungary was the fourth highest in Europe, surpassed only by that in the Baltic states. Telex quoted the head of the Hungarian Central Bank, Gyorgy Matolcsy, as saying that Hungary “has the second highest twin deficit in the EU after Romania; and next year’s inflation will be the highest (among member states) at around 15-18 per cent.”

In Slovakia, more than 200,000 pensioners found themselves below the poverty line, Noviny Joj reported in November. In its Financial Stability Report published the same month, the National Bank of Slovakia concluded that “the risks to financial stability in Slovakia are mainly in the form of inflation, the war in Ukraine, and increased economic uncertainty,” adding that, “the financial situation of some firms and, to a lesser extent, some households, will deteriorate.” Alexandra Karova, head of a homeless charity Vagus, told the Slovak daily Dennik N that she and her colleagues fear they will see more people living below the poverty line and on the streets in 2023.

At the same time as households are being squeezed by rising living costs, unemployment is starting to rise in most of the region. In its “World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2023” report, the International Labour Organization predicts that more workers will be forced to accept low quality and poorly paid jobs, which could deepen the already existing inequalities caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The IMF’s European Department warned in 2022 that the pandemic recovery has been uneven across the region, reflecting different initial conditions and policy support, and a new shockwave caused by Russia’s invasion could complicate any recovery.

1.2 Signals to watch in 2023

Economic indicators: With banks predicting continued economic uncertainty and unemployment, big challenges lie ahead for the EU and Visegrad Group of countries in Central Europe. The depth of the recessions in each country will be closely watched, though GDP data emphasizes economic decisions by consumers and companies that already took place – it’s looking backward rather than forward, which makes GDP a lagging indicator. The World Economic Forum’s “Chief Economists Outlook” in January highlighted the intensifying human impact of the cost-of-living crisis, acknowledging that households are struggling with high costs for heating and food. However, the survey indicated that “while the cost-of-living crisis may be close to its peak as policies begin to take their full effect, a majority (68 per cent) [of the economists] expect the crisis to be less severe by the end of 2023.”

War in Ukraine: Developments in Ukraine will continue to have a significant impact on the course of European countries, especially those that border Ukraine. There is a risk of escalation, with Aleksandr Lukashenko, president of Belarus, warning in February that his country is “ready to wage war, alongside the Russians, from the territory of Belarus. But only if someone – even a single soldier – enters our territory from there [Ukraine] with weapons to kill my people.” Any Russian offensive from the north would open up a new front, further destabilising the situation in the region.

Food for thought: Ukraine´s grain exports will play an important role in aggravating or alleviating the global food crisis. Ukraine has exported almost 23.6 million tonnes of grain so far in the 2022-23 season, down from the 33.5 million tonnes exported at the same stage during the previous season, Reuters reported. Although grain is still leaving Ukraine’s ports, CNN reported that experts do not expect imminent relief to the tight market conditions.

Some children form a second generation of homeless children growing up in these families – this means they were already born into homelessness.

– Alena Vachnova, chair of the board of Foundation DEDO Slovakia

Energy prices: While the EU has been struggling with an energy crisis precipitated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, experts expect the situation to ease by the end of 2023. While economists surveyed by the World Economic Forum agree that households are struggling with a cost-of-living crisis that cannot be underestimated, 64 per cent see the energy crisis easing over 2023, reflecting “the steps taken by policymakers to improve current systems, diversify supply, improve efficiency and change consumption patterns.”

Food security barometer: In 2022, the European Commission launched a dashboard on food security in the EU, aiming to present a large scale of indicators affecting food supply and food security in the EU. The EU Commission had previously developed a contingency plan to ensure food supply and food security in times of crisis, adopted in 2021, so the war in Ukraine and its impact on agricultural markets related to energy costs and trade disruptions make this dashboard an important tool. While the EU is self-sufficient for many agricultural products, the main challenge that citizens are facing is food affordability. For this reason, the dashboard will also include the rates of food inflation per type of food and per EU country and will be an important indicator for food prices.

Strikes and government responses: In the aftermath of the protests in Czechia, both Slovakia and Hungary saw a series of protests calling for higher wages in the education sector. In Slovakia, the strikes continued to spread to the health sector: with insufficient state financial support for clinics, GPs claim they have no choice but to require patients to pay additional fees for every medical examination. Tomas Szalay, a doctor in Bratislava, told Dennik N that the collapse of the medical practitioner system “has already arrived”. Experts warn that with no intervention by governments, professionals such as teachers and doctors could start resigning en masse, making essential services such as education and healthcare inaccessible to large numbers of people.

Homelessness and child poverty: To prevent an uptick in homelessness, Ruth Owen, deputy director of the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless, said: “EU member states should introduce temporary moratoria on evictions and repossessions from primary residences, as many countries did successfully during COVID-19 lockdowns.” Child poverty is also on the rise. According to a UNICEF study in October 2022 based on data collected in 22 countries across Europe and Central Asia, children now account for nearly 40 per cent of the 10.4 million additional people experiencing poverty in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

1.3 An expert view

(Alena Vachnova, chair of the Board of Directors, Foundation DEDO Slovakia, Expert on homelessness and recipient of the SDGs 2022 Award)

Poverty and inflation reached staggering levels in 2022 – more than 15 per cent in Poland and 22 per cent in Hungary. And in Slovakia, hundreds of thousands of people found themselves living below the poverty line. What do these numbers mean for the real lives of people in Slovakia and the wider region?

Even before the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, the budgets of vulnerable households in Slovakia were strained. Many people were unable to cover housing or various costs associated with their children’s school attendance and health care. Today, we see that covering the living expenses of a family or an individual is often no longer a matter of financial management. It is simply beyond the capabilities of many households – even in cases where the households earn two or multiple salaries. Simply put, while many families have been able to cut back on certain items to cover essential costs, today many have nowhere to cut back. It means that any unexpected event, such as an illness or the need to buy medications, threatens the budgets of various vulnerable households, be it single-parent families, families with several children, or senior citizens.

What can we expect in 2023?

This year is likely going to uncover more and more systemic problems impacting large groups of citizens. The first witnesses to these problems will likely be the people and organisations working directly in the field of social work. However, 2023 could also be an opportunity to create and foster a discussion in our societies about how to improve the principle of solidarity in our social systems. We can see that many individuals and politicians perceive things such as inability to access housing, poverty or unemployment as a failure of an individual, while ignoring systemic problems and various types of barriers that can cause these life situations.

This year could, as public pressure grows on the need to address the complex issues of poverty and homelessness, provide an opportunity to look at the current situation through the prism of real-time data and real experiences of organisations working in the field, instead of fuelling prejudices and narratives associated with hatred and stigmatisation of vulnerable and excluded people. It could be an opportunity to review current policies.

What has changed for people who are vulnerable to homelessness and what are the trends to watch?

The COVID-19 pandemic deepened and highlighted the existing systemic problems – for example, the growing unaffordability of housing for increasingly larger groups of people; the growing unaffordability of health care; the high thresholds for social services that are often inaccessible to the most vulnerable people. Homelessness affects not only adults, but also children, especially those growing up in encampments or shelters. Many do not have access to education for a long time, caused by a lack of access to electricity, the internet or a laptop. Many children have dropped out of the education system, which deepens their social exclusion and reduces their chances for employment in adult life.

Will there be enough services, such as emergency housing, available for people in need?

The demand for shelters is already high by default, as they often serve as a substitute for rental apartments that suffer from the growing unavailability of housing. Data collected during the Registration Week for Families with Children in Kosice in May 2021 showed that family homelessness is chronic there – the average number of years these families have been homeless for is eight years, in some cases more than 10 years. In addition, some children form a second generation of homeless children growing up in these families – this means they were born into homelessness. With the increasing number of households vulnerable to the housing crisis, the pressure on shelter infrastructure is likely to be even greater, and the challenges for the affected households will be even bigger.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News