In February 1999, a work entitled ‘War Without Limits1‘ was published by a Chinese army publisher, and it was destined to mark the course of military thought to this day, as well as influencing the course of future wars. More precisely, the work stems from the reflections of Qiao Liang (乔良) and Wang Xiangsui (王湘穗), two colonels in the Chinese army, working respectively in the Political Department of the Air Force and the Guangzhou Air Force Military District.

They start from the observation that the art of war, especially since the Gulf War, has undergone a revolution. It is being manifested, it is being fought, and it must be thought of in a way that is profoundly different from how we have known it until now. Alongside the conventional war between flesh-and-blood men who face each other pointing a rifle at each other, there are more devious, transversal, quieter and at the same time more lethal forms, which can annihilate the enemy in the blink of an eye or, on the contrary, conquer him whole and intact in deference to Sun Tzu’s art of war.

But the moral does not end in this observation, but in the final realisation that human beings, no matter how hard they try to build peace, prove unable to end war. It can be tamed in some of its aspects, but is nevertheless destined to be reborn in other forms. The aim of this study is precisely to identify these multiple senses – as Aristotle would say – of today’s war, starting from the reflections and theories of Colonels Qiao and Wang.

From hyperwar to unrestricted warfare

During Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield in the Gulf War (1991), Iraq suffered an unprecedented defeat. Saddam Hussein’s military forces capitulated within a few weeks, overwhelmed by Western technological superiority, which was so advanced as to make it possible for the Americans to use ‘zero kills’ tactics. It was a true revolution in military history. Former US Navy General John Allen coined the term ‘hyperwar’ to describe the conflict fought with the new autonomously guided weapons: Tomahawk missiles guided by artificial intelligence, infrared spy satellites, laser-guided Hellfire missiles, F-117th stealth fighters, F-15E, F-111, F-16 fighter-bombers, J-STAR radar planes; in the desert, M-1A1 tanks, aided by the Q-37 computerised radar system, with twice the range of Iraqi tanks, marched simultaneously. American and allied forces could act literally undisturbed, remote-controlling their weapons from convenient control rooms, without having to sacrifice ‘our boys’. To all this must be added the allied reinforcements of the Atlantic Pact and the UN; the pressure from international institutions, together with the countermeasures of states, which did not have too many reservations about implementing embargoes to the detriment of civilians; a media mobilisation that saw the press agencies unanimously strive to create a narrative to the detriment of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

The speed of execution, the power of the technologies employed, the vast international mobilisation, and the lethality of the economic countermeasures brought to the attention of the Chinese and other powers the following question: how to defend oneself and at the same time wage war against such a militarily and economically powerful enemy?

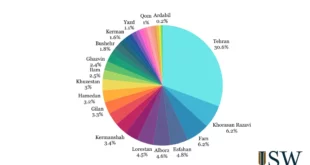

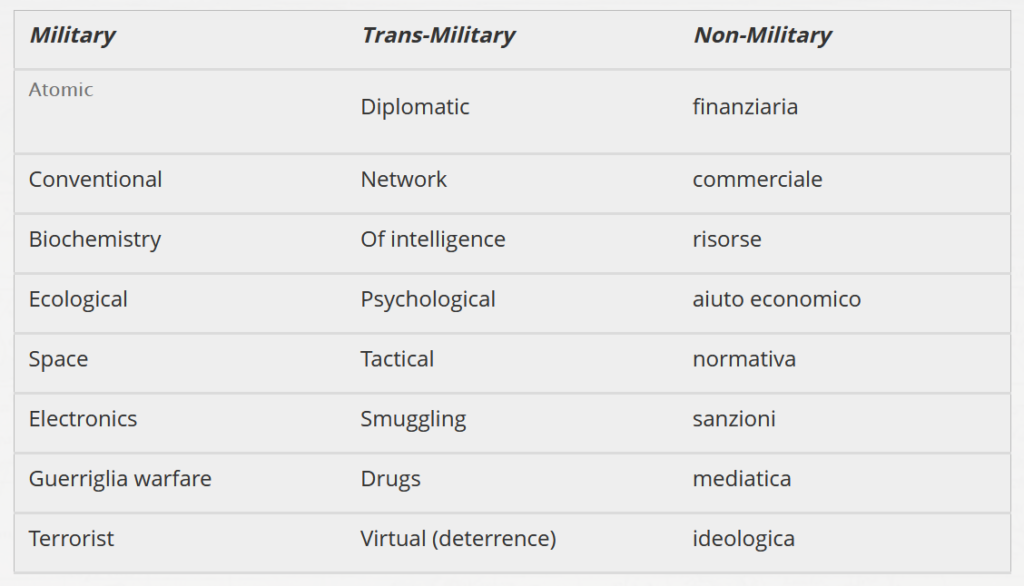

Therein lies the concept of unrestricted warfare: war is no longer to be understood solely in its classical meaning, i.e. an armed conflict between national governments in the course of which at least 1,000 people are killed [2]. In its broadest sense, war can – and in fact does – take place on innumerable battlefields, completely unsuspected and apparently far removed from the semantics of conflict. Economic experts, financiers and bankers today have the ability to provoke economic crises to the detriment of entire global regions; a computer hacker could cause a power grid blackout or disrupt a country’s vital infrastructure; an ordinary citizen can spread defamatory material on the internet or put pressure to influence a particular individual; terrorist groups have become the nightmare of sovereign states, yet the imbalance of forces and resources between the parties is immeasurable. The issue also involves the very institutions used to resolve conflicts: international organisations such as the European Union, the International Monetary Fund, NGOs. No one escapes the cruel ‘consequences of peace’ as Keynes would say. Qiao and Wang have identified as many as 24 operational methods classified into three macro-sets[3]; the constant in each element is ‘war’:

Furthermore, what unites the different areas of warfare are the following common ‘essential principles’, the very essence of limitless war[4]:

Omnidirectionality: all-round observation, planning and intervention

Synchrony: conducting actions in different spaces within the same timeframe

Limited objectives: defining action within an acceptable radius for the available means

Unlimited means: tendency to unlimited use of means and criteria, but restricted to achieving the aim

Asymmetry: contours of balance

Minimum consumption: use of the least possible amount of resources

Multidimensional coordination: selection and allocation of all forces that can be mobilised

Control and correction of the whole processToday’s wars involve the combination of two or more methods of operation. The choice is most often dictated by circumstances, but in fact remains at the discretion of the strategies, the tactical imagination of the warriors. In any case, the real skill lies in the ability to push beyond the limits imposed by military conventions. It changes the very concept of the battlefield: it is itself everywhere, in any domain[5]. There are no fixed laws or always perfect combinations; victory depends on individual circumstances, as well as countless other factors. The authors, after reviewing the historical successes of some of the greatest classical military strategists[6], have come to the conclusion that in general, the one who has achieved the right combination wins[7].

The asymmetric war between the US and Bin Laden, to name a few examples, has seen the war of domestic terrorism combine with intelligence, financial, regulatory and network wars. The ongoing war between Ukraine, aided by the entire Atlantic West and Russia, has the exact same essence of unlimited war: we have in fact seen economic intervention by the European Union in support of the Ukrainians + financial sanctions by the world’s financial institutions + political sanctions by the UN + court rulings by the International Criminal Court against Putin, along with a gigantic media propaganda war on both sides and countless other operational methods among the already mentioned (atomic, electronic, psychological, diplomatic deterrence, etc.). ). The UN, the International Criminal Court, the SWIFT financial mechanism, the European Union: following the doctrine of unrestricted warfare are all parties to wars fought through unconventional but equally lethal weapons. Every political veto, every hacking, every foreign university, every duty paid by the enemy is a bullet fired. It is no coincidence that the Chinese colonels call both Shoko Asahara, Japanese terrorist, and George Soros, shark of world finance, soldiers.

Terrorism and asymmetric warfare

The terrorist is par excellence the combatant in an asymmetrical war: a conflict between opponents who on paper are clearly unequal. However, a terrorist group, unlike a sovereign state, has no scruples about breaking international rules per se (indeed, it is often the aim of terrorism), they do not feel bound to abide by rules in the trenches; therefore, they are more inclined to carry out unorthodox measures, in particular the killing of civilians. Terrorism uses the rule of law as a weapon against the enemy state or organisation. Al-Baghdadi does not give a damn about conventions protecting cultural property when he decides to deface Nineveh and Palmyra. On the contrary, ISIS uses the card of lawlessness to send a message to the world, or at least to as many ears as possible. It is unthinkable for the state to fight with the same weapons, the tactic of putting out fire with fire does not work here. Moreover, a state has a huge arsenal compared to terrorist rebels, but for this very reason, terrorists are well advised not to confront the state enemy directly; therefore, the huge monopoly of force becomes useless, if not counterproductive. Other operational methods are needed, such as intelligence, psychological warfare, financial warfare… Strictly military operational methods are impossible.

From 1994 to 1995, the Aum Shinrikyo religious sect terrorised Japan with attacks on stations and subways, dispersing sarin gas and hydrogen cyanide among civilians, claiming dozens of victims. Their strategy was precisely to choose victims and public places in order to confuse police inferences. Unlike Al-Baghdadi, the Japanese leader Shoko Asahara did not come from the military. His actions came from the thinking of an intellectual, which did not arouse the slightest suspicion about the lethal capabilities he later demonstrated. Against a danger of this nature, the work of the forces of law and order is delicate, in proportion to the degree of importance attached to democracy and civil rights. Maintaining a democratic society places additional responsibilities on public institutions. In contrast, it would certainly be easier for a deeply authoritarian regime to intervene with repressive measures. Terrorism uses limited methods to wage unlimited war[8]. The state’s problem is exactly the opposite.

The soldiers of finance

The destructive potential of a commercial or financial crisis should be known more or less to anyone who has been alive for at least twenty years. It is no coincidence that Sun Tzu’s great classic on the art of war is taught and made to read in many schools of corporate finance management. Few bank officials or financial sharks are capable of destabilising entire regions of the globe.

One of the best known and most important, still in action today, is the Hungarian Ashkenazi George Soros. In the summer of 1992, one year before the future signing of the Maastricht Treaty, it was decided in the wake of the Delors report that the member states of the then European Community should adapt to the narrow band of fluctuations (precisely to the level of 2.5 per cent from parity). The news was in itself an open invitation for financial speculators to take advantage of the imminent currency devaluation that was bound to occur in the European member states of the system. Soros did not miss the opportunity and speculated on both the British pound and the Italian lira, so much so that he made a multi-billion dollar profit and on the other hand caused a dramatic crisis in their respective countries, so much so that in September of that year they left the European Monetary System. In London that speculation is still remembered today as ‘Black Wednesday’, while in Italy that summer – not surprisingly – other samurai of the economy such as Mario Draghi, Ciampi and Andreatta were planning the future dismemberment of Italian public assets.

The big capital holders, rating agencies, bureaucrats and bankers have in their hands weapons infinitely more dangerous for the fate of entire nations than a Leopard tank. In today’s globalised world, a presentiment (sentiment) of an economic crisis in a region, bank or sector can trigger a capital flight that can bring a government to its knees. Capital mobilisation can either attract useful investments from abroad or make them disappear immediately with all the disastrous consequences that follow. Large financial agents like Soros voluntarily use large amounts of capital to bring states or governments hostile to their interests into crisis, and at the same time influence others.

Again Soros was among those responsible in the 1990s, together with IMF officials, for the severe economic crisis that knocked out the so-called Asian tigers. Countries like South Korea, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia were the most promising economies at the time. However, the IMF interfered in the management of their policies, persuading governments to adopt its economic recommendations in the wake of the so-called Washington Consensus, especially in the areas of market liberalisation, corporate restructuring and currency revaluation. Countries such as South Korea and Mahathir’s Malaysia, less inclined to embrace the policies of Western foreign agencies, managed not to capitulate completely and continue to grow in the long run; Indonesia and Thailand, on the other hand, could not withstand the infiltration of the Camdessus-led IMF and suffered a devastating crisis: Indonesia was left with 75 per cent of its companies in default in 1998, a 13.1 per cent fall in GDP and a subsequent civil war; Thailand saw its output fall by 10.8 per cent along with 50 per cent of its bank loans default[9]. Such numbers are usually caused by repeated bombings and armed wars of attrition.

Since 2008 we have also experienced in the West the crash of the global economy, which started with a real estate crisis in the US. There, too, actions by officials in suits and ties at rating agencies have been the bane of global financial health. Bureaucrats at Moody’s S&P, Mackinsey then used the weapons of bond ratings to subvert democratically elected governments and blackmail sovereign states. We saw this in Italy during the last Berlusconi government, hastily ousted so that it could give way to Mario Monti’s government of neoliberal reforms (Berlusconi’s government was the victim of a highly financial + media combinatorial attack). So did the Greece of Tzipras, who in the space of a year went from plans to leave the EU to the economic default that tore the country apart, causing famine and death[10]. Confirming that financial markets are the greatest threat to peace[11] it should be remembered that former German chancellor Hellmuth Kohl used the Deutschmark to tear down the Berlin Wall[12]. Soros still finances NGOs, news agencies, politically active think tanks[13]; his Open Society Foundation has financed insurgent groups and political experts to subvert regimes hostile to him. His capital is behind the Maidan Square protests[14], which started the long war between Kiev and the Russians in the Donbass. Today his finances continue to forage the asymmetric troops of the various Azov, Pravy Sektor and Svoboda sending hundreds of thousands of young Ukrainians to slaughter.

And the trade war? It too responds to the cold, crude logic of universal warfare. However, an important difference lies in the actors involved: usually a trade war concerns two states or economic regions (such as the European Union or NAFTA states); the conflict takes place at the level of so-called high politics, i.e. at the level of foreign policy between state political entities. Duties, economic sanctions, export subsidies are adopted in order to harm the hostis on the economic battlefield. But it has already been seen that the damage affects the very lives of individual citizens, so much so that a duty on imports of a certain good, such as those on Chinese products adopted by Trump’s US government[15], can interrupt the source of income of many Chinese companies that live from exports and perhaps only from exports to the US. Thus, they send ordinary workers of a country to the brink. The warlords do not carry uniforms and bayonets, but textbooks of international and commercial law.

Cyberwarfare and psychological warfare

Above we have just mentioned the two ‘classic’ operational methods for unlimited warfare – terrorism and finance – used to achieve objectives in asymmetrical warfare. But in the hypermodern world they only concern a small slice of the fields where conflicts arise. Not only financial sharks like Soros or charismatic leaders leading terrorist groups. Even a boy with inventiveness and a notebook in his hands is easily able to hack into the computer systems of a public office and endanger the public information apparatus. As already mentioned, cyberwarfare has the highest priority in the art of battle. The modest resources required and, conversely, the extreme extent of the damage a hacker attack can cause, makes the demand for these new cyber soldiers exponentially increasing. In 2007, Estonia suffered a major cyber attack, which caused a temporary collapse of the country, knocked out essential services, and blocked banking transactions. In 2010, a virus attack called Stutnex disabled the Iranian nuclear power plant in Natanz. Both situations have a lowest common denominator: minimum investment (common IT means) maximum yield (compromise of vital infrastructure; national scope).

In recent years, psychological wars through the new mass media must also be added. We are at a point now where each one of us, if equipped with a smartphone, is already in himself, whether aware or not, willingly or unwillingly, a potential soldier. More precisely, the smartphone we hold in our hands is a weapon capable of panoptically infiltrating everyone’s lives. The enemy today, be it a data-hungry company or a rival work colleague, enters our homes. A family concerned about its children’s accessibility to the influences of the outside world can no longer rely on the safety of the home. On the contrary, the owners of the symbolic broadcasting media strike us in the psyche from morning to night. Through smart media, we are perpetually attacked by signals from advertisements, (dis)information sites, advertisements, propaganda videos, commercial music, etc., all correlated by causal necessity. All related by causal necessity to the Orwellian control of our lives. Big Data is the new issue at stake and the technological means employed are so pervasive that they put the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century to shame.

Another noteworthy feature of this new asymmetrical war is the mammoth disproportion between the players in the field: on the one hand, multi-billion dollar giants that give sovereign states a run for their money, and on the other, ordinary citizens who are often completely unaware that they are the objects, not to say victims, of this bio-power. Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Marck Zuckerberg, Elon Musk, etc. are rightfully among the ranks of soldiers in the field of a psychological war for the ‘control of hearts and minds’, as the doctrine of containment was described at the origins of the Cold War. All of us are as individuals:

Inferior combatants in an asymmetrical vertical war, against public or corporate powers.

Equal combatants in a horizontal unlimited war; each individual as an individual against the other individual(s)Another detail, already anticipated, characteristic of unlimited warfare concerns the blurring of the distinction between military and civil. The boundaries between military and civil technology or mentality become blurred. Zhang Yiming, the founder of Tik Tok, moves between the civil market and the use of data obtained by the government for intelligence purposes[16], just as it emerged from the Cambridge Analytica case that Facebook used data for political purposes. Among other things, it emerged that the Chinese brand platform offers completely different personalised services at home than in the rest of the world. A Tik Tok user in Los Angeles will initially find himself inundated with junk content, with nothing culturally useful; usually it is purely artistic-popular entertainment or demented comedy content. On the contrary, the algorithm offers Chinese citizens more virtuous content, often of a motivational and patriotic nature, highlighting situations or people who perform publicly meritorious actions. The message is clear: China seeks to wage psychological warfare against the Americans by weakening them morally. The adversaries use the same platforms for exactly the same purpose. And it should be remembered that the victims and executioners do not have uniforms or AK-47s in their hands, but – to the extent that individuals are the content creators – we are all directly engaged in the trenches.

Conclusion

There are infinite ways of combining the operational methods with which to conduct today’s wars. Biological weapons are no different: what was covid-19 if not a pathogenic bomb, whether it was released or got out of hand? Even the directives of bodies such as the WHO destabilise the functioning of state machinery and consequently our lives. Add to this the fact that 80% of the funding the WHO receives comes not from states, but from private pharmaceutical companies, most of them owned by Bill Gates, and the die is cast. The recent events at Azovstal in Mariuopol have brought to light the Ukrainian bio-laboratories in which biological weapons of mass destruction were being tested. Not to mention environmentalism, in fact a climate war, with NGO activists engaged in moral persuasion on governments and civil society to change energy policies the former and mindsets the latter. Here too, a separate chapter would have to be opened on the relationship between science and war.

For the moment, the ‘classic’ ways – terrorism, finance, information technology – of waging unlimited war have been mentioned. Paraphrasing Carl von Clausewitz, it is not war that is the continuation of politics, but rather the opposite: politics is one of the ways to continue war by other means. Despite the building of international institutions of peace in the aftermath of the Second World War, we are far from the thought of an end to history that would bring about a world without conflict. The hostile act, the stone thrown, the look of defiance, the bullying at work, the search for consensus and the maintenance of one’s own interests, right up to the defence of one’s own nation and the worldwide ideological war to establish a ‘consensus’. These are all inherent to human nature, at least of modern man. The animus dominandi as Hans Morgenthau called it confirms that the Latins were right when they said si vis pacem para bellum.

“War is always the terrain of death and life […] Even if one day all weapons were to become completely humane, a less bloody war in which bloodshed could be avoided would still be a war. Perhaps its heinous process could be changed, but there is no way to change its essence, which is one of coercion, and therefore it is not even possible to change its cruel outcome.

Bibliography

Qiao Liang Wang Xiangsui, Guerra senza limiti, 2019

Manlio Dinucci, L’arte della guerra, 2015

Jospeh Stiglitz, La globalizzazione e i suoi oppositori, 2002

Sun Tzu, L’arte della guerra, 2016

Robert Jackson, Georg Sorensen, Relazioni Internazionali, 2018

Luciano Segreto, l’economia mondiale dopo la guerra fredda, 2018

Lotta Harbom and Peter Wallensteen, Armed Conflicts, 1946-2009, 2009

Kerry Liu, Chinese manufacturing in the shadow of the China-US trade war, Institute of economic affairs, 2018

Stelios Stylianidis, Kyriakos Souliotis, The impact of the long-lasting socioeconomic crisis in Greece 2019

Sitography

[1] Qui si fa riferimento all’edizione italiana pubblicata per la prima volta nel 2001 dalla casa editrice LEG: Qiao Liang, Wang Xiangsui, Guerra senza limiti, traduzione di Rossella Bagnardi e Roberta Gefter, 2019[2] Armed Conflicts, 1946-2009, Lotta Harbom and Peter Wallensteen, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 47, No. 4 (july 2010), pp. 501-509

[3] Qiao Wang op.cit. p.129

[4] Ivi p.183

[5] Ivi p.74

[6] Re Wu, Alessandro Magno, Gustavo Adolfo di Svezia, Napoleone, Schwarzkopf, ivi p.120-123

[7] ibidem

[8] Ivi p.24

[9] J. Stiglitz, La globalizzazione e i suoi oppositori, Einaudi, 2002, p.97

[10] https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2019/05/03/grecia-fubini-non-ho-voluto-scrivere-che-dopo-la-crisi-sono-morti-700-bambini-in-piu…. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6357520/pdf/S2056474017000319a.pdf

[11] https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-aug-23-op-15742-story.html

[12] Qiao Wang ivi p.83

[13] https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/newsroom/soros-and-open-society-foundations-give-100-million-human-rights-watch

[14] https://st.ilsole24ore.com/art/notizie/2014-12-03/se-soros-e-finanza-scelgono-governo-dell-ucraina-084934.shtml

[15] Kerry Liu, Chinese manufacturing in the shadow of the China-US trade war, Institute of economic affairs, 2018

[16] https://www.cisecurity.org/insights/blog/why-tiktok-is-the-latest-security-threat

[17] Qiao Wang ivi p.64

Source: https://www.ideeazione.com/unrestricted-warfare-dalliperguerra-alla-guerra-illimitata/

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News