Plentiful resources contribute to long-term success if channeled to the development of institutions, but Azerbaijan, like many other autocracies, is instead using them to burnish its image abroad and cement the status quo.

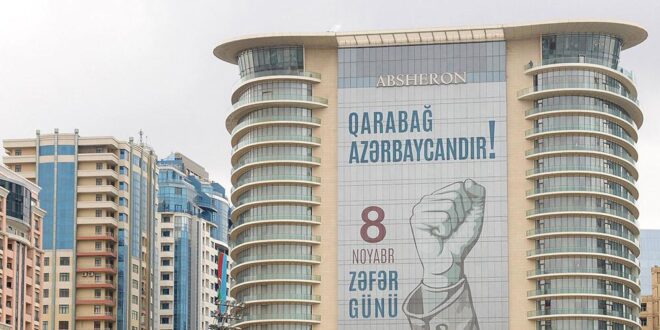

Since the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, news out of Azerbaijan has been an unending series of announcements about achievements and victories. It remains to be seen, however, whether the current success is sustainable.

Baku’s biggest triumph in recent years has undoubtedly been almost complete resolving the complicated and long-running territorial dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh in its favor. Following Azerbaijan’s victory in the 2020 war, those forcibly evicted by Armenians three decades ago have begun to return home, though so far, only a few hundred of the 700,000 people who originally fled the disputed territory and Armenia have returned. The main thing for Baku, however, is that the process is finally under way after decades of waiting.

Azerbaijan’s other foreign policy successes only add to the sense of optimism. The country looks set to make big profits on the European energy market, which is desperate for oil and gas after Russian supplies nearly ended amid the war in Ukraine.

The extraction and export of natural gas is growing, and there are ongoing negotiations about the construction of new branches of the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) and the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) that link Caspian gas fields to Italy. Several Balkan countries that the pipelines pass through are ready to switch from Russian to Azerbaijani gas. EU leaders have called Baku a “reliable” partner that is making a significant contribution toward “security of supply.”

All this is happening without any significant concessions by Baku to the West. On the contrary: Azerbaijan is conducting itself rather crudely, not hiding its ire at the Western leaders who sympathize with Armenians, like French President Emmanuel Macron.

Gone are the days when Baku attempted to be liked in the West by financing the restoration of sites including the Sistine Chapel, thousand-year-old churches in France, and the catacombs in Rome. After victory in the Nagorno-Karabakh war, Baku halted such overtures, disappointed that European society mostly remained supportive of Armenia.

Nor has Baku been shy about criticizing Moscow. There has been a flurry of official diplomatic protests: over statements by State Duma deputies, comments made on talk shows, and the reasons for disagreements with Russian peacekeepers stationed in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Baku’s assertiveness is even visible when it comes to extremely sensitive issues for Russia. Most telling of all was Aliyev’s meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky on June 1: the leaders of Belarus, Armenia, and the Central Asian nations could not possibly allow themselves to meet with Putin’s antagonist.

Still, it’s not all plain sailing. Azerbaijan is still using the coronavirus pandemic to justify its closed land borders, which make it impossible to enter the country from Russia, Georgia, or Iran. The two exceptions are the tiny land border between Turkey and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan, and the post in Lachin corridor linking Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, which remain open.

It is hard to find any medical explanation for this policy so long after the pandemic. It is more plausible that the domestic situation in Azerbaijan is not that stellar, and the authorities fear that excessive contacts with the neighbors may ignite serious trouble.

Both Azerbaijan and Iran adhere to the Shia branch of Islam, but the two countries’ relations are increasingly strained due to Baku’s growing apprehension about importing religious radicalism.

In the case of Russia, the Azerbaijani authorities would rather avoid the influx of Russians fleeing mobilization or political repression. In Armenia and Georgia, it made prices skyrocket, while Azerbaijan is already struggling with inflation—food prices rose by nearly 20 percent last year—so there is likely an aversion to taking on any extra economic risks.

Another danger the regime faces is that the successful return of territory in Nagorno-Karabakh is fueling rising domestic expectations. For many years, revanchism was at the cornerstone of the ideology of the Aliyev regime. What happens if successful revanchism does not yield what many hoped it would?

Above all, this concerns the repopulation of Nagorno-Karabakh, a project that has few parallels in modern history. It’s crucial for Baku that there should be no discontent among the returnees. But given the Azerbaijani system, that is unlikely—when the most fertile land ends up in the hands of those with the best connections, for example. While Azerbaijanis are still euphoric over their military success, in a few years it may be important to them that villages in Nagorno-Karabakh are not Potemkin villages.

There are other risks, too. While Azerbaijan has boosted its international standing by increasing gas deliveries to Europe, this is no panacea. The experience of other post-Soviet states suggests that without social justice and political accountability, even petrodollars, foreign investment, and military victory are not enough to guarantee stability. Widespread disappointment could easily explode into protests if it is fueled by anger over growing corruption and widening inequality.

The Azerbaijani regime is lucky to have reached this stage of its development at a comparatively favorable moment in time. It is not threatened by the senility of an eternal leader (Aliyev is only sixty-one years old) or external pressure. Europe is more dependent than ever on new gas supplies, and that means Western politicians will not pay too much attention to the fate of the Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh.

On the other hand, this sort of halcyon era has already been experienced by other post-Soviet countries—for example, Russia and Belarus—and it ended without achieving sustainable prosperity. Plentiful resources contribute to long-term success if channeled to the development of institutions, but Azerbaijan, like other autocracies, is instead using them to burnish its image abroad and cement the status quo.

Inevitably, such a system is vulnerable. A good example is Kazakhstan, which also appeared to be enjoying a rare run of success until it was convulsed by unrest in January 2022. If Azerbaijan likewise experiences such social discontent, the situation would be exacerbated by the large number of men with military experience, the proximity of unfriendly Iran, and widening inequality typical for many resource-rich autocracies. The consequences could be dire.

By:

Kirill Krivosheev

End of document

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News