Central banks may keep interest rates higher for longer than currently priced; given investors’ benign inflation outlook and growing expectations for a soft landing, this could increase financial stability risks and weigh on growth

Overall inflation has moderated meaningfully in recent months in the United States and euro area, as energy and food prices have fallen significantly. Year-on-year headline inflation is now around 3 percent in the United States and below 5.5 percent in the euro area. However, core inflation, excluding food and energy prices, has declined more slowly. Services inflation has proven to be particularly sticky.

According to market pricing, investors expect headline inflation to continue to decline quite rapidly in coming quarters. However, some market participants still see upside risks to the inflation outlook, likely reflecting recent stickiness in core inflation. Indeed, pricing from inflation options—financial instruments that offer protection against inflation moving higher or lower than its current level—shows that such upside risk is particularly pronounced in Europe, where investors assign roughly similar odds to inflation returning to the European Central Bank’s 2 percent target and inflation remaining around 4 percent. In the United States, investors appear to put high odds on inflation being above target at around 3 percent.

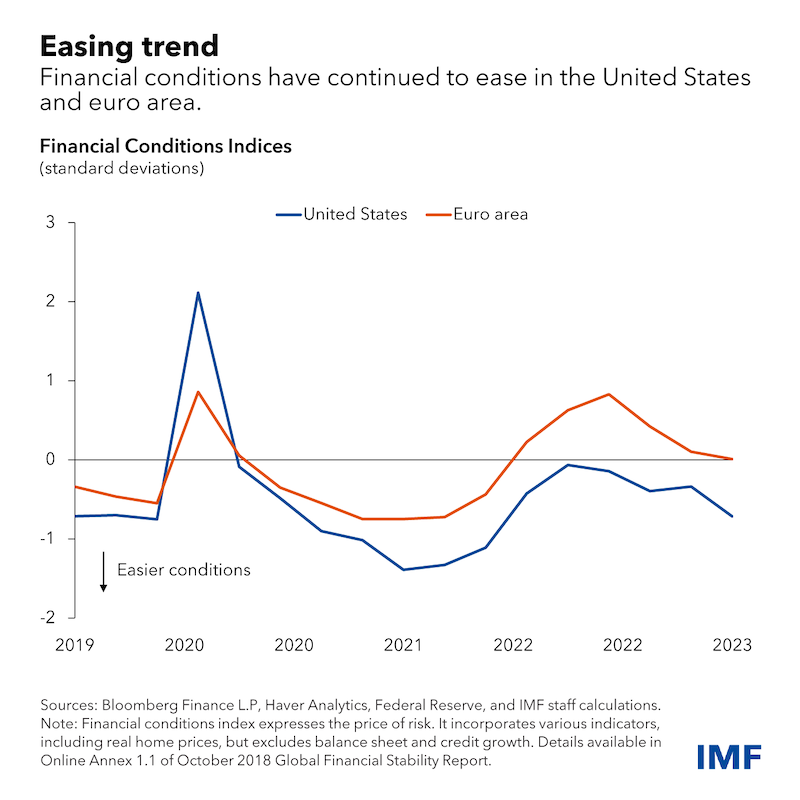

At the same time, financial conditions—as proxied by our index that summarizes financing costs faced by firms and households in housing, credit, and equity markets—have eased notably in the United States and euro area in recent quarters. This easing has occurred despite continued monetary policy tightening by the Federal Reserve and ECB, in part reflecting investors’ relatively benign outlook for price pressures—an assessment that has boosted market valuations.

The recent easing creates a challenge for central banks in their efforts to get inflation back to their 2 percent targets. Historically, tighter monetary policy has been transmitted to the real economy, and subsequently to inflation, through tighter financial conditions. While financial conditions are currently tighter than the extremely loose levels seen in mid-2021, the recent easing may complicate the fight against inflation by preventing the slowdown in aggregate demand that may be needed to tamp down inflation pressures.

A further complication results from the combination of a prolonged period of extremely loose financial conditions and a monetary policy tightening cycle in advanced economies that started when inflation was already elevated. This may have dulled the transmission of monetary policy to financial conditions. For example, the share of fixed-rate mortgages with low rates (because of refinancings in the past few years) is very high in the United States. Similarly, corporations took advantage of exceptionally low borrowing costs and ample liquidity to extend their debt maturities.

In both cases, this may have dampened the effectiveness of monetary policy tightening, as many mortgage holders and companies have only begun to face higher borrowing costs, thus contributing to the continued strength in labor markets and aggregate demand. Of course, other factors may have played a role, including structural changes in the labor marker or housing markets after the pandemic, for example.

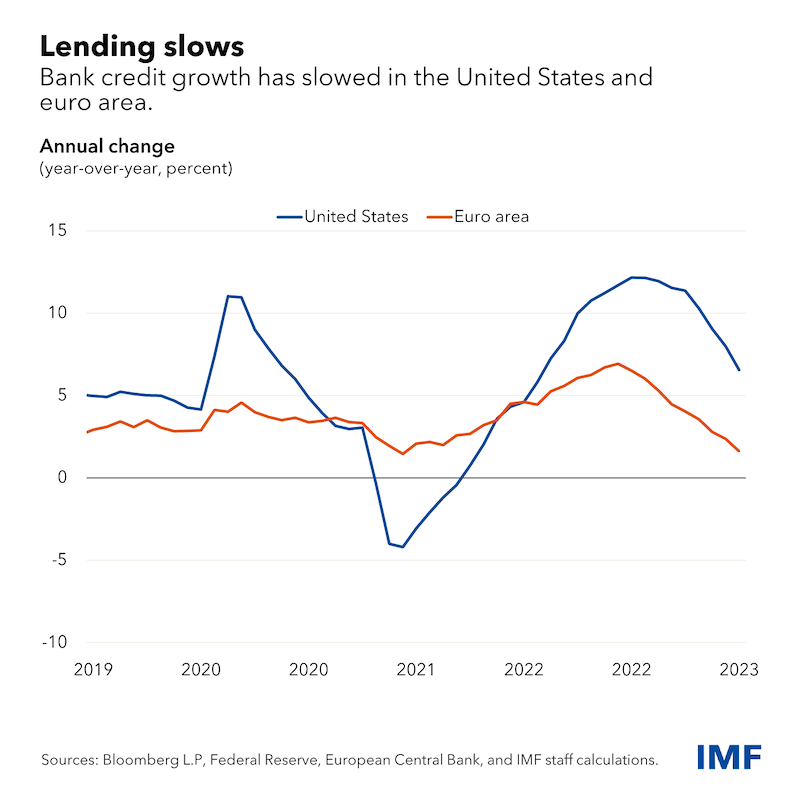

While financial condition indices based on financing costs in capital markets have eased, monetary policy transmission also works through credit extension, especially for borrowers more reliant on bank lending. Bank credit growth has remained positive in both the United States and euro area, although the pace of growth has slowed markedly, especially in the latter. More forward-looking information in recent loan officer surveys in both the United States and euro area point to significantly slower demand for credit and tightening underwriting standards by banks, suggesting that a further deceleration in bank credit provision may be in the offing. Recent earnings reports have shown strength at large banks, with earnings boosted by higher interest rates charged on loans while remuneration on deposits continues to lag the pace of policy tightening. Lending survey results, however, suggest that profitability could moderate going forward.

Nonbank credit provision may also be slowing, with corporate bond issuance down significantly this year. Importantly, we also see a pronounced differentiation: while issuers with high credit ratings continue to be able to borrow relatively easily, their lower-rated counterparts face greater headwinds. Default rates are starting to increase among lower-rated borrowers, albeit from low levels, along with bankruptcies at small and medium-sized enterprises. This suggests the credit cycle may be deteriorating.

Monetary policy has always operated with considerable lags, and the pace and timing of transmission of the tightening remains uncertain, particularly given possible structural changes in the economy due to the pandemic and rising geopolitical tensions. The central narrative among market participants is one of a benign soft landing, where inflation returns to target relatively quickly with only a modest slowdown in economic growth. While IMF’s baseline outlook doesn’t foresee recession in the United States or euro area, core inflation is expected to be more persistent than what is priced in markets, and consequently, further policy tightening is assumed.

But a scenario where underlying inflation continues to be sticky and declines only slowly is a risk. Tighter monetary policy for longer than currently priced by financial markets may be needed, resulting in higher real interest rates. This could hurt investor sentiment as market participants reassess the inflation and policy outlook, leading to a repricing of risk assets such as equities and credit and to a tightening of financial conditions. Such an outcome could heighten risks to economic activity and financial stability.

Potential vulnerabilities

From a financial stability standpoint, strategies predicated on a fast disinflation process and a soft landing could be vulnerable to an abrupt tightening in financial conditions and the unwinding of highly leveraged investment strategies may lead to disorderly market conditions.

For example, there are now widespread reports and anecdotal evidence in the United States of investors financing purchases of Treasury securities and simultaneously selling futures contracts to capture profits from the difference in prices. A sudden shock, for example related to upside surprises to inflation, may cause a widening of such price differences and force leveraged investors to unwind their positions, selling bonds just as the prices for those securities fall. The potential for an adverse feedback loop between such forced selling and banks that do not have the balance sheet capacity or willingness to buy these securities could lead to stress in markets and present financial stability challenges reminiscent of those that shook Treasury markets in March 2020 at the onset of the pandemic.

In addition, some segments in the US banking sector remain vulnerable as regional lenders may continue to face profitability issues in the quarters to come. The March banking turmoil in the United States and the government-supported sale of Credit Suisse underscored that managerial and supervisory failures can make banks vulnerable to shifts in market sentiment, with investor runs amplified by technology and social media.

Both pricing and positioning suggest that investors are perhaps too optimistic about the speed of disinflation and the likelihood of a soft landing in economic activity. Core inflation remains sticky, suggesting that inflation (and the risk of a resurgence) has not yet been fully tamed. History cautions against declaring victory too soon. Central banks must remain determined in their fight until there is tangible evidence that inflation is sustainably moving toward targets.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News