Attacks by Yemen’s Huthi rebels in the Red Sea have caused shipping companies to avoid the Suez Canal — a key source of revenue for Egypt as it battles a deep economic crisis.

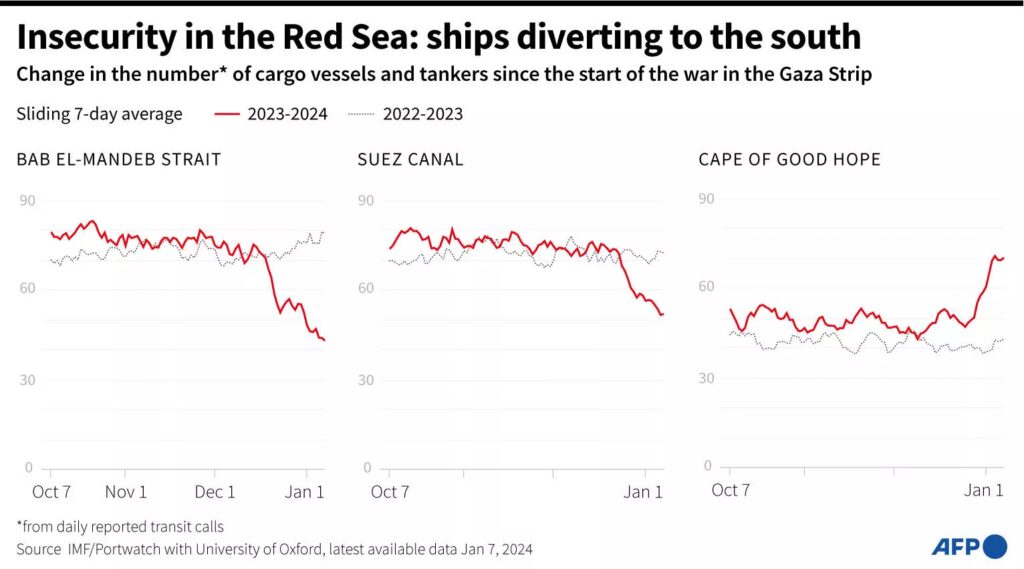

International Monetary Fund figures show 35 percent less cargo was transported through the Suez Canal in the first week of 2024 compared with the same period last year.

Analysts say the financial impact, though limited for now, will become painful if Huthi attacks keep throttling traffic through the main maritime artery connecting Europe and Asia.

The man-made waterway — which officially opened in 1869 — is crucial for Egypt, earning it $9.4 billion in transit fees in the fiscal year 2022/23.

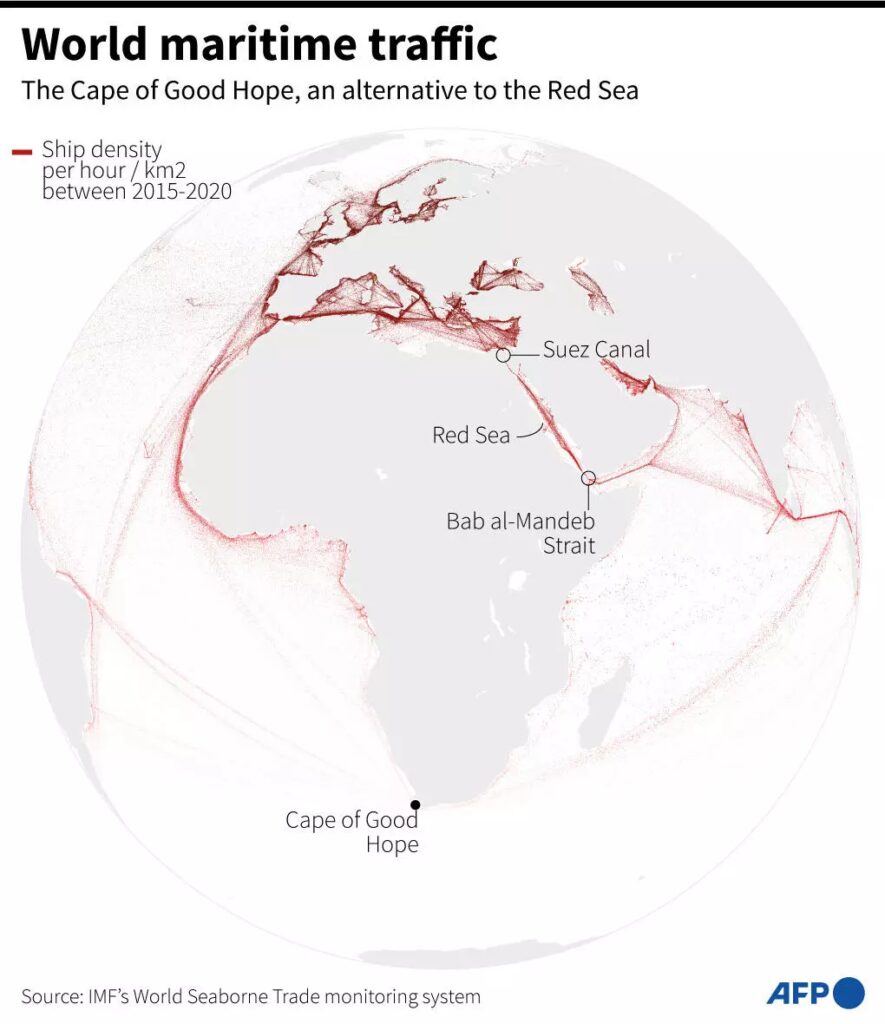

Since the Iran-backed Huthis began attacking ships in response to Israel’s bombardment of the Gaza Strip, companies have opted for the far longer route around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope.

The route circumnavigating Africa saw a 67.5 percent jump in cargo compared with the same period last year, said the IMF’s PortWatch.

Citing the highly volatile situation, which has driven up insurance costs, Danish shipping giant Maersk said Friday it would divert all vessels away from the Red Sea for the “foreseeable future”.

Since November 18, 25 commercial vessels have been attacked in the southern Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, according to the US military.

The Huthis — part of the Iran-aligned “axis of resistance” against Israel — say the strikes are in solidarity with Palestinians.

Israel has bombarded the Hamas-run territory for three months in a campaign to destroy the militant group after the October 7 attack.

US and UK forces shot down more than 20 drones and missiles over the Red Sea launched by the Huthis, in what London branded Wednesday the “largest attack” yet by the Iran-backed rebels.

Vital shipping lane

The Yemeni rebels says they are targeting Israel-linked commercial ships transiting the vital shipping lane, in solidarity with Palestinians.

The narrow strip of sea — stretching from the Bab al-Mandeb Strait in the south to Egypt’s Suez Canal in the north — provides passage for 12 percent of world trade, according to the International Chamber of Shipping.

Apprehensive even after the US launched a naval coalition that now patrols the Red Sea, shipping companies are willing to shoulder the cost of the longer route, according to Paul Tourret, head of maritime commerce institute ISEMAR.

He said the additional fuel cost is offset by saving on hefty fees for using the Egyptian waterway so that going around Africa, though more time-consuming, “ends up being about the same price”.

The New York-based Soufan Center think tank argued that, though “freight rates have almost tripled” since the disruptions began, costs remain lower than during the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the impact of the crisis “will grow if it lasts”, a port official told AFP, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Suez Canal revenues are especially vital for Egypt amid the economic crisis during which the local currency has lost half its value since March 2022 while inflation tops 35 percent.

Egypt’s economy also relies heavily on tourism and on remittances from Egyptian workers abroad, which fell almost 30 percent in July-September 2023 on year, according to the central bank.

Amid the downturn, the Arab world’s most populous country has relied heavily on Suez Canal income both for its military and for social welfare spending.

At least two-thirds of the Egyptian population live on or below the poverty line.

“Canal revenues help keep the lid on the social pressure cooker,” said Tourret. “They go directly to the state, which reinvests them in the military and social welfare.”

The recent decline in shipping traffic, he said, had caused “a real shortfall. One month could be all right, but two months will be cause for concern.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News