Putin’s war on Ukraine marks the end of the near abroad—the idea that Russia enjoys a special status in much of the post-Soviet space. But while Russia’s neighbors are seeking greater independence, they are not necessarily turning West.

By November 2022, nine months into Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, tens of thousands of middle-class Russians had fled their homeland to make new lives in Central Asia. A chocolate company in Kazakhstan chose the moment to release a commercial.1 The viewer sees a curly-haired young Russian backpacker struggling wearily across a grassy steppe landscape, dragging a suitcase. A man in traditional Kazakh dress on horseback rides up and presents the backpacker with a bar of chocolate. “What is it?” asks the young Russian. “The taste of freedom,” replies the proud Kazakh.

The ad played on a reversal of fortunes and a switching of roles between Russia and its neighbors as a result of the war in Ukraine. Russians were choosing to “taste freedom” that they could no longer enjoy in Russia itself by relocating to countries such as Armenia, Georgia, or Kazakhstan. In doing so, they challenged deeply ingrained hegemonic assumptions of what was the metropolis—Russia—and what was the periphery in the post-Soviet space.

The war in Ukraine marks a historical juncture for more countries than just Ukraine and Russia. Thirty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the conflict registers the end of the idea of the “near abroad”—the notion that Russia enjoys a special status with its post-Soviet neighbors. Most of Russia’s neighbors have not disengaged from Russia, however: in the context of war, they have sought to rebalance the relationship by strengthening partnerships with other international actors while still dealing with Russia. In a new international environment, a careful and differentiated approach is needed to deal with an increasingly complex group of countries.

Sovereignty Reasserted

All around Russia’s borders, national elites are reasserting their sovereignty. All of the post-Soviet states except Russia’s close ally, Belarus, have sought to check and deter Russia’s behavior by either supporting Ukraine or abstaining in United Nations (UN) resolutions and rejecting Russia’s claim to annex Ukrainian territories. For some governments, particularly those of the two democracies of Armenia and Moldova, this is a moment to try to break free of Russian control. For others, an assertion of sovereignty is less about decoupling from Russia than about enhancing security while rebalancing the relationship to their advantage—especially as there is plenty of money to be earned from increased trade with Russia after economic relations with the West have broken down.

Along Russia’s borders, the war in Ukraine has accentuated feelings of alienation and rejection of Moscow’s ambition to be a metropolis and a hegemon. Public opinion polls reflect a sharp increase in negative sentiments toward Russia, especially in countries with ties to the West. In Moldova, the number of those who say that relations with Russia are good fell from 53 percent in 2019 to 23 percent in 2023.2 In Armenia, the plunge was even steeper, from 93 percent to 31 percent over the same period.3 In Georgia, despite a government-level rapprochement with Moscow since 2022, the war in Ukraine has deepened public antipathy toward Russia. A 2023 poll found that only 11 percent of Georgian respondents agreed with the idea that “Georgia will benefit from abandoning European integration in favor of better relations with Russia.4

These sentiments reflect a societal shift that has been underway for some time. Knowledge of the Russian language has steadily declined outside Russia’s borders. In 2021, for example, only 60 percent of Georgians and 74 percent of Armenians reported that they had an intermediate or good grasp of the language.5 The comparative figure for Azerbaijanis in 2013, the last year in which the same poll was conducted, was 35 percent.6 The trend is sharpest among the younger post-Soviet generation, including elite figures. When the prime minister of Georgia, born in 1978, held talks with his Armenian counterpart, born in 1975, in Yerevan in March 2024, they spoke in English.7

There is also a turn away from Russian media in neighboring countries, even in Kazakhstan, where Russian vies with Kazakh as the language of everyday communication. The consumption of Russian cultural outputs was already in decline in many of these countries and has fallen further. Georgia and Moldova have restricted access to Russian television channels, although it is still possible to watch them online. In Armenia, the influential Russian channel Sputnik had its license suspended for thirty days in December 2023 after comments by one broadcaster were deemed offensive.8 A 2023 survey in Moldova by the WatchDog pollster found that 27.5 percent of respondents considered Russian-language information sources to be reliable. That was a fairly sharp decline from 2021, when the figure was 42.9 percent.9

Three caveats should be added here. The first is that in each of these countries, there remains a significant minority that expresses loyalty toward Russia and can be exploited by the regime of President Vladimir Putin. Second, a turn away from Russia does not mean a turn toward democracy. By exchanging Russia for Kazakhstan, fleeing Russians are not escaping to a country that is free by other criteria. Kazakhstan’s Freedom House ranking for democratic standards is only marginally higher than Russia’s.10 These Russians are instead finding refuge in a foreign jurisdiction that is asserting its right to be a sovereign state free from Russian interference.

That leads to a third caveat: many of these countries may be staking out greater independence from Russia, but that does not mean that they are turning West. Other partners, notably China and Turkey, are available. Aside from Ukraine, only one state in this group—Moldova—is heading at full speed toward Europe. As the war in Ukraine continues into a third year with both Ukraine and Russia undefeated, most Eurasian governments are keeping their geopolitical options open.

Russia the Disrupter

The group of men in the Russian elite, led by Putin, who decided to invade Ukraine in 2022 had intended to demonstrate something different: the return of a strong, hegemonic Russia endowed with a privileged status in the former Soviet neighborhood. This looks more like an attitude and an assumption than a doctrine. Russian official documents do not flesh out what this status means in practice nor what the incentives are for other countries to cleave more closely to Russia.

Russia’s March 2023 foreign policy concept had more to say about the West and the rest of the world than about the neighborhood.11 A section entitled “Near Abroad” set a goal of “establishing an integrated economic and political space in Eurasia in the long term.” The section’s main emphasis was on deterring the influence of other states by “preventing and countering unfriendly actions of foreign states and their alliances, which provoke disintegration processes in the near abroad and create obstacles to the exercise of the sovereign right of Russia’s allies and partners to deepen their comprehensive cooperation with Russia.”

There is an obvious contradiction here. Other states are allowed a “sovereign right” to cooperate and integrate with Russia—but with no one else. As was the case in the Soviet era, the model of cooperation is a hub-and-spoke design in which all relations are with a central arbiter, Moscow.

Putin promoted integrationist projects from early in his presidency. His first design for a regional economic organization, the Eurasian Economic Community, dates back to 2003 but was only formalized as a more substantial project, the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), in 2015. It had five members, including Russia—but not, as Putin had planned, Ukraine. The flaw of the EAEU, experts have noted, was that it was not a collaborative project but a bloc made to the design of one core power, Russia. The EAEU’s economic rationale was entangled with security concerns, as Russia saw the other members of the union not merely as economic partners but also as an ideological and political buffer against the West.12

Putin’s war of aggression in Ukraine looks in part to have been a belated and desperate response to the failure of softer integration projects. Full-blooded neo-imperialism filled the vacuum. Much of the Russian public discourse since the start of the war is even cruder than that of Putin himself. The war has given a safe space to commentators to make open threats against Russia’s neighbors and say in public what was until recently unsayable, without suffering consequences.

For example, in February 2024, Vladimir Soloviev, a well-known host on Channel One, Russia’s main state television channel, publicly threatened both Armenia and Georgia. He said with regret that Russia should have fully occupied Georgia in 2008, as this would also have stopped Armenia from moving West.13 He said, “There would be no problem with Armenia if we had not stopped [military action] in Georgia in 2008.” The normalization of this neo-imperialist discourse makes Russia look like a disrupter, rather than a reliable partner, and disqualifies the country’s claim to be a dependable security patron for its neighbors. Russia is seen more as a threat than as a protector.

Russia’s arbitrary behavior calls into question a central tenet of the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), founded in 2002 and modeled in part on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO): the principle of mutual defense. Armenia first questioned the CSTO’s utility when the country did not receive the assistance the organization was supposed to provide after Azerbaijani forces crossed Armenia’s border in September 2022. In February 2024, Armenian officials said they had frozen their involvement in the CSTO. The organization also did not intervene after border incursions by Tajikistan into Kyrgyzstan in September 2022, which raised questions about whether Central Asian states could rely on Moscow for protection.14

The failure of the CSTO to take action—apart from in Kazakhstan in January 2022, when it intervened to support the country’s president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, against unrest—makes Russia an inherently unreliable security actor in the country’s south and east. In a situation where other security actors, such as China, the European Union (EU), and Turkey, also lack capacity, this inaction makes for a potential security vacuum in both the South Caucasus and Central Asia.

A Hierarchy of Interests

The post-Soviet space, or the former Soviet Union, is a historically correct term but a politically and geographically problematic one in 2024, because it still defines countries thousands of miles apart by a state that has not existed for three decades. No single term has emerged to replace it, apart from the very unspecific word “Eurasia.” This lexical gap underlines the fact that little now unites, say, Moldova and Tajikistan except their shared—and receding—Soviet past.

Russia’s interests are and were very different across this space. Even when the countries in question were parts of the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union, there was much to differentiate them. For Russian leaders historically, Belarus and Ukraine have generally been viewed as places of vital historical and strategic interest—up to the point that the current elite from Putin on down now denies Ukraine’s right to exist as a state at all. For example, former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev said in March 2024, “Ukraine is definitely Russia. Historic parts of the country need to come home.”15

Russia’s nineteenth-century conquests of western provinces and the South Caucasus were driven less by ideological motives and more by an ambition to create a buffer zone against Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the Ottoman and Persian Empires and establish secure trade routes. In these parts of the empire, conquest was often followed by the co-optation of local leaders, some of whom were given a career path to join the Russian elite.16

At the same time, the Muslim peoples of Central Asia and the North Caucasus underwent full-scale imperial conquest and forced Russification. The surnames of Central Asian, Azerbaijani, and North Caucasian subjects were Russified, and their languages were written in the Cyrillic alphabet. A colonial mindset persisted into the Soviet era especially strongly in these regions, as ethnic Russians and other Slavs were presumed to have a superior status to other ethnicities. By the late Soviet period, many Russians held the view that Central Asia and the Caucasus were more of an imperial burden than an asset for Russia.17

A similar hierarchy of interests applies for today’s Russia. Central Asia is less an area of strategic interest than are other parts of the former Soviet space, even though, paradoxically, conditions there are more favorable for Russia. Moscow is helped there by a Russian-speaking elite that was formed in Soviet times as well as by geography and geopolitics. Western countries have stepped up their rapprochement with the region since 2022 but run up against many constraints. Kazakhstan, in particular, must tread carefully with Moscow as the country has not only a 4,800-mile-long border with Russia but also a large Russian-speaking minority population.

In the west and the south, the different approaches Russia has taken toward various conflicts, which date back to the 1990s, are instructive. For example, Crimea, which most Russians consider a historic Russian territory, was fully annexed by Russia from Ukraine in 2014. Eight and a half years later, Moscow declared four provinces of eastern and southern Ukraine to be parts of Russia.

By contrast, the Russian leadership—although not the Russian parliament—has never questioned the territorial integrity of post-Soviet Moldova and has declined calls by Transdniestria to recognize it as independent. Moscow accepts that the region is part of Moldova, and although Russia supports it with free gas, Russia has allowed its military presence there to dwindle since the 1990s to very low levels. Transdniestria itself has kept a low profile during the war in Ukraine; the territory’s economy is semi-integrated with that of Moldova and many of Transdniestria’s citizens now hold Moldovan passports.18

Russia’s current strategy looks to be to win back Moldova politically by supporting pro-Russia candidates in the 2024 Moldovan presidential election and sponsoring Russia’s proxies in Moldova’s autonomous region of Gagauzia. This is not to exclude the possibility of a so-called project maximum of taking over Moldova fully if Russia ever succeeds in capturing the nearby Ukrainian port of Odesa on the Black Sea, adjacent to Transdniestria. But current Russian policy toward Moldova is not as aggressively ambitious as it is in Ukraine or Belarus.19

The South Caucasus is different again. There, the war in Ukraine has confirmed how it is now almost impossible for Russia to maintain its traditional ambition to be a regional power broker and security umbrella. In September 2023, Moscow broke with long-standing practice and stood down a peacekeeping force on the ground when it allowed Azerbaijan to take over another disputed territory, Armenian-populated Nagorny Karabakh, by force. The Russian peacekeepers who had been deployed there since 2020 stood by in what looked to be either inaction or a deal with Baku. In April 2024, they began to withdraw from the region. These developments contributed to a drastic breakdown in relations between Russia and its traditional protégé, Armenia.

Russia’s climbdown in Karabakh reflected a new calculus forced on Moscow by the war in Ukraine. The drain of conflict and encirclement by the West mean that Moscow can no longer afford the same hard-power posture in the South Caucasus. Azerbaijan, which lies on Russia’s main trade and transportation route to the south, became Moscow’s main partner and much more needed than Armenia—even if that came at the expense of giving up boots on the ground.

This calculated strategic retreat leaves Russia in a quandary with regard to the third country in the South Caucasus: Georgia. Since 2022, the Russian and Georgian governments have embarked on a quiet rapprochement by improving trade links and restoring flights. Meanwhile, the Georgian Dream leadership declines to offer Ukraine much public support and signals that it is staying out of the war.20

However, Moscow and Tbilisi have had no diplomatic relations since 2008, when Russia recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent—and effectively annexed them. This situation leaves Russia in de facto control of the two small territories but with no clear path to winning back political influence in Georgia itself. This is a scenario that some Russian politicians and experts had predicted. As Alexei Malashenko said in 2009, “I am sure that over time, South Ossetia will become more and more of a hindrance to Russia and resemble a ‘suitcase without a handle,’ which is hard to drag but sad to abandon.”21

The Near Abroad

The idea of the near abroad is more than thirty years old. It was born in late 1991, when the Soviet Union was dissolved and tens of millions of people woke up in one of fifteen newly independent countries. At the time, observers looked on the end of the Soviet Union as perhaps the most peaceful dissolution of an empire in history. Despite several smaller conflicts, fears of large-scale war between the new states—or, worse, nuclear conflagration—proved unjustified.

In 1992, there was also qualified optimism in the West that Russia could seize the chance, under a democratically elected government, to emerge as a new nation-state that had shed an imperial burden. This hope was at least in part borne out, as Russian president Boris Yeltsin’s administration, because of either incapacity or strategic vision, exercised restraint—at least against his country’s post-Soviet neighbors. (No such restraint was exercised against Chechnya within Russia’s borders.)

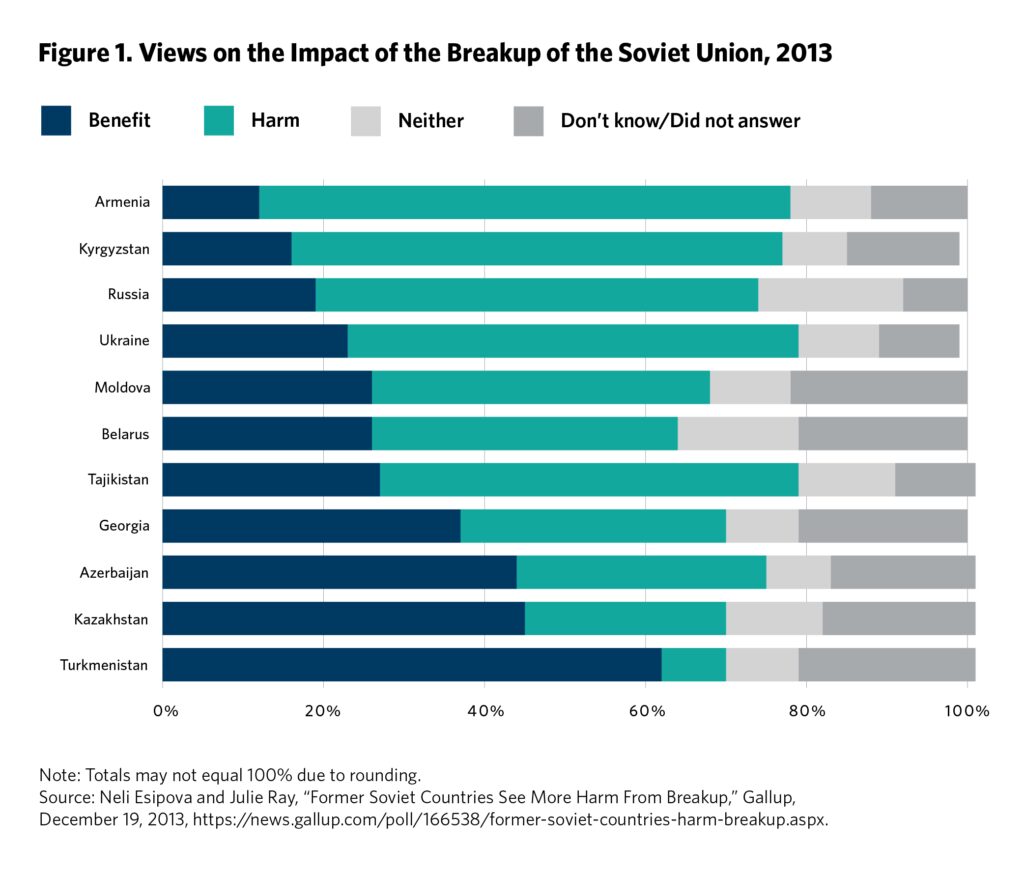

The new status quo was always fragile and potentially reversible, however. The Soviet Union lived on in people’s heads long after it had actually disappeared. Even in 2013, a Gallup poll found that citizens of seven out of eleven post-Soviet countries believed that the end of the Soviet Union had delivered more harm than benefit—most obviously in a decline in living standards in the 1990s. In Russia, the divide was sharp, with 55 percent of respondents saying the collapse had harmed the country and 19 percent believing it had been a benefit (see figure 1).22

Moreover, in 1992, the terms of the Soviet breakup and Russia’s new borders did not correspond to Russians’ mental conception of where the bounds of their homeland should be. That was especially true when it came to Crimea. Prominent Russian newspaper editor Vitaly Tretyakov was certainly not alone in voicing the thought that “it is a strange Russia that includes Chechnya but excludes Crimea.”23

The term “near abroad” was used to describe this new reality. As political scientist Gerard Toal put it, the phrase “simultaneously named a new arrangement of sovereignty and an old familiarity, a longstanding spatial entitlement and a range of geopolitical emotions.”24 In the Yeltsin years at least, the relatively benign assumption prevailed that the term described a transitional phase that would allow millions of Russians to adapt to the reality of no longer living in a common state.

The near abroad was institutionalized as the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), a grouping of twelve post-Soviet countries that did not include the Baltic states. One analyst called the CIS a “shock absorber” that “cushioned the blow” of the end of the Soviet Union.25 Yet, Russia’s ambition in the early 1990s for the organization to be a tightly integrated group of states with Russia at its core was frustrated. All of the eleven non-Russian independent states moved to assert their unassailable sovereignty in the form of new currencies, institutions, and international partnerships.

One issue of concern was that millions of people who identified as Russian and lived in Estonia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, and Ukraine, in particular, could behave or be manipulated in a way that would be a source of instability or subversion. Despite the rhetoric of nationalist politicians, the Yeltsin administration mostly trod carefully on this issue. As it turned out, most of the people concerned identified more as Soviet than as Russian. In economic and political terms, they were more embedded in their home republics than the Russian nationalists who claimed to champion their interests had anticipated. Alexei Firsov, the director of the Platforma center, which conducted polling on this issue in seven post-Soviet countries in 2023, said, “There is no strong identification of Russians with Russia. Overwhelmingly they see themselves as citizens of their countries, while the older generation more often considers the [Soviet Union], not Russia, as their homeland.”26

The Soviet Legacy

The relationship between Russia and its neighbors is shaped by a Soviet history of unequal power relations and constructed nationalism that still manifests itself in many different ways.

The Soviet Union is generally called an empire, but it was an unusual one. After seizing power, the Bolsheviks formally espoused an anti-imperialist ideology as they dismantled the core institutions of the tsarist empire: the monarchy, the aristocracy, and the church. At the same time, they reconquered territory by force and rebuilt a state that was recognizably imperial. Soviet borders roughly corresponded to those of the former Russian Empire. As in tsarist times, Russia was the core of the new state and Moscow was its metropolis. In the late 1920s, the Russian language and Russian culture were restored to the heart of state ideology and the state honored Russian imperial historical heroes. The Soviet leadership was Russian speaking, if not always ethnically Russian, as non-Russians could join elite circles as long as they spoke Russian and adopted certain mores.27

Both the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire also differed from other European empires in that their core territory, Russia, remained more backward than several parts of the empire. The main national group, Russians, lived no better economically, and Russian ethnonationalism was kept in check. Moscow, not Russia, was the center, as there were fewer political institutions in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic than in other republics.28 In an essay that compared the Soviet Union to a “communal apartment,” historian Yuri Slezkine defined Russia’s Soviet-era paradox by saying that “Russia both owned the entire communal apartment and had no room of its own.”29

A multinational identity also persisted at both a political and a cultural level. Over the lifespan of the Soviet Union, most minority nationalities kept greater language and education rights than in China, Iran, or Turkey, for example. As political scientist Jeffrey Mankoff wrote, “both Soviet and post-Soviet leaders similarly prioritized imperial preservation over valorization of ethnic claims. Unlike the rulers of Nationalist China, Kemalist Turkey, or Pahlavi Iran, they never portrayed their country as a nation-state, and allowed ethnic minorities varying degrees of cultural and political autonomy.30

The Soviet Union was, in principle if not in practice, a construction of fifteen constituent union republics with equal rights. Territory was classified by nationality. A national status was allocated to each Soviet citizen, and a titular national group was granted special rights within the borders of each territory. This process created a series of new Soviet national elites who belonged to the titular nationalities of their union or autonomous republics and accrued power for themselves at a local level. In the late 1980s, as the center weakened, political elites in the non-Russian republics and then in the Russian Federation itself under Yeltsin used their nominal rights first to bargain for greater autonomy from the center and later to seek and win independence.

In effect, Soviet rule was a Russian matryoshka doll of power relations that formed a hierarchical structure of abuse akin to that of the Soviet prison system. Moscow, as the center, had supreme power and, especially in the Stalin era, used it to harshly control the national republics and decimate cultural elites and disloyal cadres. In parallel, elites in the national republics enjoyed powers of coercion within their borders. Union republics became, within certain limits, fiefdoms and proto-nation-states. Much of the heroic national iconography and statuary in post-Soviet countries dates from Soviet times. The same titular elite groups kept power for decades in many republics. They built up institutions, such as academies of science, to legitimize their status and controlled patronage and economic networks to the detriment of minority populations and territories.31

The legacies of these Soviet power relationships are manifold and still palpable. One legacy is in elite politics. In many places, Soviet-era titular elite groups either took power in 1992 or returned to power soon after a brief hiatus in the 1990s. They built up their newly independent states as bastions of sovereignty not only against Moscow but also in terms of domestic politics and ideology. These elites treat politics as a zero-sum game and have sought to keep their power intact either with or without democratic processes.32

Another legacy is conflict, especially in the Caucasus. In the late 1980s, when smaller nationalities—Abkhaz, Chechens, Nagorny Karabakh Armenians, and Ossetians—were the titular elites in charge of smaller autonomous territories within the union republics, power-sharing disputes deteriorated into outright conflict. Trying to resist assimilation into the would-be independent union republics, elites in autonomous regions, such as Abkhazia and Transdniestria, found common cause with the Soviet center in the 1980s to work against the regional centers of power in Baku, Tbilisi, or Chişinău. In the early 1990s, Abkhaz, Ossetians, and Transdniestrians still looked to Moscow and received military help from Russian security and military structures.

Soviet-era zero-sum thinking is also manifested in other majority-minority disputes. With titular elite groups still controlling most state institutions, minority communities are often viewed through a security lens or as potential agents of Russia. Thus, a 2021 poll in Georgia found that 47 percent of respondents viewed the country’s ethnic and linguistic minorities as a “potential security threat” after the wars in the 1990s.33 In 2022, there were casualties during protests in Uzbekistan’s autonomous region of Karakalpakstan against attempts to downgrade the territory’s status within the country.34

A further persistent legacy lingers from the hub-and-spoke design of the Soviet Union. There is poor regional cooperation in the South Caucasus and Central Asia, as elites guard their economic and political sovereignty and choose not to cooperate across borders. This stands in contrast to the three Baltic states, which prioritized regional cooperation over national sovereignty even before they all joined the EU in 2004 and then adopted the euro as their currency. The lack of regional cooperation or solidarity across most of the former Soviet Union is exploited by Russia, which can pursue relations with each country on a bilateral basis, rather than having to deal with the collective positions of more than one state.

Russia’s Post-Soviet Choices

In 1992, relations between Russia and its neighbors depended on the uncertain evolution of the Russian Federation, as a new nation-state, and of its postimperial identity. Post-Soviet, postimperial Russia had no clear path to follow. The end of Russia’s preeminent but poorly defined status in Soviet times could be seen variously as a tragedy or an opportunity. Leadership was a crucial factor: a Russian leader could draw on and instrumentalize many alternative visions of Russia and its neighborhood.

In the 1990s and 2000s, various politicians and thinkers presented starkly different visions of Russia’s role vis-à-vis the former Soviet republics. Most of these outlooks had in common an assumption of Russia’s entitled preeminence in the neighborhood, but their policy prescriptions were very different. Four such visions illustrate the divergent paths Russia’s leaders could have chosen to follow.

Two of these views belonged to post-Soviet Russia’s most eminent Slavophile, the Nobel Prize–winning author Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and one of its most famous Westernizers, Anatoly Chubais. Despite the high profiles of the two men, neither thesis won approval from the decisionmakers of the time.

In 1990, Solzhenitsyn published a long essay entitled “Rebuilding Russia,” in which he set out an argument for a reconstituted Russian Empire.35 Called a “Russian Union,” this entity would consist of the three main Slavic republics of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine as well as northern Kazakhstan with its large Russian-speaking population. Solzhenitsyn argued that the borders of the Soviet Union had been artificially created to divide brotherly Slavic peoples. He said that Ukrainians should be allowed to determine their own future but at a local level, with each region voting on where it should belong. The rest of the Soviet Union—the Baltic states, Moldova, Central Asia, and the Caucasus—should be allowed to be separate.

Solzhenitsyn’s essay was not militaristic, and much of it was devoted to a favorite theme of his: the need for local self-government in Russia. But it naturally alarmed people in Kazakhstan and Ukraine in particular. It is interesting to note, however, that his espousal of a revision of borders had no mainstream resonance at the time.

Chubais, the architect of many of post-Soviet Russia’s biggest market reforms, laid out a very different conception of Russia’s post-Soviet role in a long 2003 essay that advocated the paradoxical idea that Russia should be a “liberal empire.” He said that Russia should undertake the “mission” in its neighborhood of promoting democracy and the free market: “A liberal empire should rest not on bayonets but on Russia’s attractiveness—on the image of our country, our state, as a source of justice and protection.”36 Admitting that his use of the word “empire” was a provocation, Chubais said that the protection of Russian culture and the Russian language, as well as Russia’s business interests, should go hand in hand with the “support, development, and, if necessary, protection of basic democratic institutions, rights, and the freedom of citizens in neighboring countries.”

If neither of these proposals had any traction with the policymakers of that era, the same could not be said of the third vision, devised by Yevgeny Primakov, who was first Russia’s foreign minister and then prime minister between 1998 and 1999.

Primakov, one of the leading figures in the perestroika team of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, was the favorite to be Russia’s next president before Putin was made prime minister and Yeltsin’s heir apparent in 1999. Primakov was a so-called Russian statist, who wanted to strengthen the Russian state and its institutions. He also promoted the doctrine of a multipolar world, in which Russia would not follow Western interests, as after the end of the Soviet Union, but be a regional pole. On becoming Russia’s foreign minister in 1996, Primakov defined Russia’s top foreign policy priority as “the strengthening of centripetal tendencies on the territory of the former [Soviet Union].”37 He promoted integrationist projects with Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan and tried, unsuccessfully, to strengthen the CIS.

Primakov differed from Russia’s current elite, however, in respecting the post-Soviet sovereignty of the new states and trying to pursue his goals by economic and political means. He favored diplomacy over force and called for greater roles for the UN and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in the post-Soviet space. He brokered the lease agreement for Russia’s Black Sea Fleet in Crimea and cautioned against Yeltsin’s 1994 military intervention in Chechnya. In 1997, Primakov tried to coerce the Abkhaz leadership into reintegration with Georgia, and in 2008, he opposed Russia’s recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states.38 According to one of his associates, he believed that this step would mean Russia “losing” Georgia.39

In his memoirs, Primakov wrote that Russians needed to change their psychology toward their neighbors, writing of Ukraine, for example, “Russians ought not to be upset that diplomats in Kiev who speak Russian better than Ukrainian (at the moment!) write us notes in the Ukrainian language and hold press conferences in that language. We have to get used to this being normal – they are representing their own Ukrainian state and not another one.”40

Primakov’s integrationist plans failed. One can assume that if he, rather than Putin, had been elected Russian president in 2000, he would have engaged in geopolitical contestation with the West as he asserted Russia’s right to be a pole in a multipolar world. However, it is hard to imagine that the cautious and diplomatic Primakov would have led Russia into conflicts with its neighbors as Putin subsequently did.

Yet another approach came from Alexei Navalny, Putin’s most serious political opponent over the last decade before his death in February 2024. Navalny labeled himself an “anti-imperialist nationalist.”41 His views evolved over time from supporting Russia’s 2008 military intervention in Georgia to strongly opposing the war in Ukraine in 2022.42 Navalny argued that Russia had been right to shed its empire and that it should not get involved in foreign military adventures. He did this from what he called a nationalist perspective, saying Russia’s top priority was to tackle its domestic problems, such as poverty, alcoholism, and a low birth rate.

Navalny also supported the nationalist slogan “Stop Feeding the Caucasus,” suggesting that Moscow should stop giving generous subsidies to Chechnya and other North Caucasian republics. He repeated the mantra that he wanted Russia “to become a normal country” and argued that “we no longer have enemies we need to fight.”43 His foreign policy vision was of a Russia that did less outside its borders to do more at home.

These very different visions of Russia’s post-Soviet future show paths not taken. They underline the importance of leadership and belie the notion that Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine was an inevitable culmination of Russian policy since 1991. And yet, the importance of leadership and Russia’s autocratic political culture also meant that once Putin made the decision, he was able to rely on the full support of the elite and, at least passively, of most of the Russian population.

Putin—L’État, c’est moi

Putin’s approach to the near abroad has evolved since he became president in 2000 and is closely tied to his own domestic fortunes and need to build public legitimacy. Defining Putin’s ideology is not easy, and most observers have commented on how malleable it is.44 Putin’s 2021 historical essay on Ukraine established him as a man of neo-imperialist views and obsessed with Russian history. But even the word “imperialist” is almost flattering to Putin in that it implies a coherent civilizational vision for neighboring countries, which is not obvious from his policies.

Putin’s official Russian state discourse is founded on a defensive posture that is fixated on Russia’s perceived enemies. This discourse has much more to say about the past than the future. Two constants in the Russian leader’s ideology are that he is a statist and an exceptionalist. Both of these ideas resonate with the Russian public, especially people of an older generation who still feel a sense of trauma over the loss of the Soviet Union. In a 2005 speech to the Russian parliament, Putin famously called the end of the Soviet Union the “calamity of the century.”45 The main thrust of the argument that followed, however, was that it was his duty to build a strong Russian state and not to allow the new Russia to collapse, as the Soviet Union had done before him.

Increasingly, Putin transferred this language of an existential threat and potential state failure to his descriptions of Russia’s foreign relations. In 2007, he told foreign interlocutors at the Valdai Discussion Club, a Moscow-based think tank, “Sovereignty is therefore something very precious today, something exclusive, you could even say. Russia cannot exist without defending its sovereignty. Russia will either be independent and sovereign or will most likely not exist at all.”46 These fears were Putin’s justification for strengthening the Russian state against various threats: Islamist insurgencies, NATO enlargement, or the so-called color revolutions allegedly instigated by the West in neighboring states.

By Putin’s exceptionalist way of thinking, some states are more sovereign than others. In 2007, he said, “Frankly speaking, there are not so many countries in the world today that have the good fortune to say they are sovereign. You can count them on your fingers: China, India, Russia and a few other countries. All other countries are to a large extent dependent either on each other or on bloc leaders.”47 By extension, when it comes to the other former Soviet states, as Russia experts Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy have written, this means that “for Putin, Russia is the only sovereign state in this neighborhood. None of the other states, in his view, has truly independent standing—they all have contingent sovereignty. The only question for Putin is which of the real sovereign powers (Russia or the United States) prevails in deciding where the borders of the New Yalta finally end up after 2014.”48

In August 2008, shortly after Russia’s five-day war with Georgia, when Russia openly revised the 1991 settlement of post-Soviet states’ borders for the first time, Medvedev explicitly argued for Russia’s right to a sphere of influence in its neighborhood.49 He said, “Russia, just like other countries in the world, has regions where it has its privileged interests. In these regions, there are countries with which we have traditionally had friendly cordial relations, historically special relations.”

There can be little doubt that Putin believes in the neo-imperialist, historical, exceptionalist discourse he has now perfected; but it has also suited him very well to advance these beliefs as a legitimizing strategy for his own continued rule. Putin’s doubling down on aggressive, conservative ideas in his foreign policy coincided with his return to power in 2012 and his moves to impose more authoritarian rule at home. By returning to the Kremlin, he broke a pledge that he would serve only two terms as president.

Putin’s return was premised on the self-serving notion that whatever constitutional niceties were being overturned, Russia could not survive without a strong leader at the helm. Not for the first time in Russian history, this stance has inevitably led to an identification of the leader with the state. Putin is never so much an imperialist as when he sees himself as an emperor. An emperor has the right to change his mind, break promises, declare new enemies, and, most importantly, rule in perpetuity.

Public legitimacy is an important part of this construction. Loyalty is never to be taken for granted. As Russia watchers Sam Greene and Graeme Robertson have written, Putin’s Russia is in part a “co-construction” between the Putin regime and large parts of Russian society—a project heavily manipulated by the regime and official media.50 As Russia’s domestic social and economic policies have increasingly failed to deliver promised results, Putin has bought public loyalty by emphasizing Russia’s supposed greatness in its neighborhood and the world. Since 2007, when Russia waged its first serious confrontation with a post-Soviet neighbor—a cyberwar with Estonia—the Kremlin has instrumentalized alleged enemies and crises in the neighborhood to buttress domestic legitimacy.

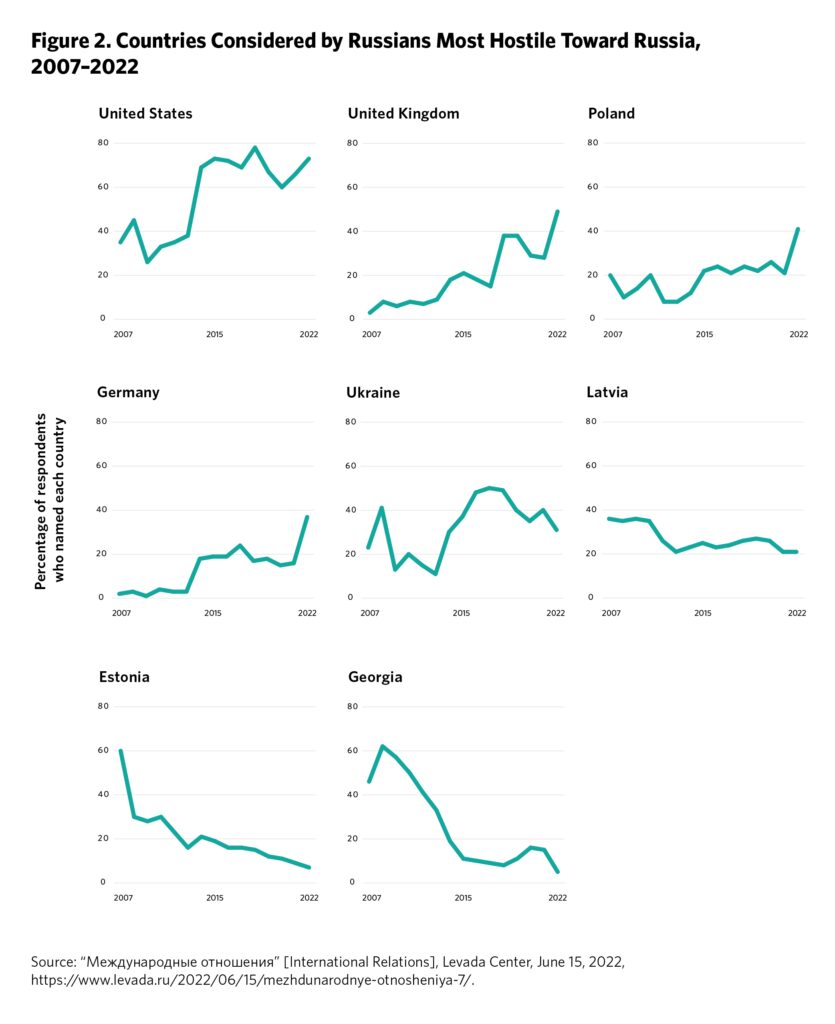

For almost two decades, the Levada Center has conducted polls that ask Russians to name five countries they consider to be Russia’s enemies. The strong fluctuation in answers over time shows how the Kremlin propagates a narrative—disseminated through Russian state television, in particular—that shapes public opinion. The narrative and the main enemy changes: from Estonia in 2007 to Georgia in 2008; Ukraine was viewed particularly negatively in 2009, when there were disputes over gas supplies, and again after 2014 (see figure 2). Anyone can be named an enemy, but once the media spotlight moves elsewhere, public sentiments of hostility can abate quite quickly.

Over the years, Putin has repeated and intensified the message that Russia’s conflicts with its neighbors are proxy battles in an existential war with the West. This narrative, in turn, validates his agenda that his own personal rule is the key component that protects Russia from losing that war and saves the Russian state from collapse.

Russian society, however, is not as monolithic as Putin would wish it to be. The World Values Survey, conducted in sixty-four countries, showed in 2017 that Russia was the European country where most people felt “further from Europe” and that Russians had low levels of trust in institutions.51 Yet, the survey also revealed that large numbers of Russians had become more individualist and more socially liberal—on a level with most Eastern European countries, such as Ukraine.

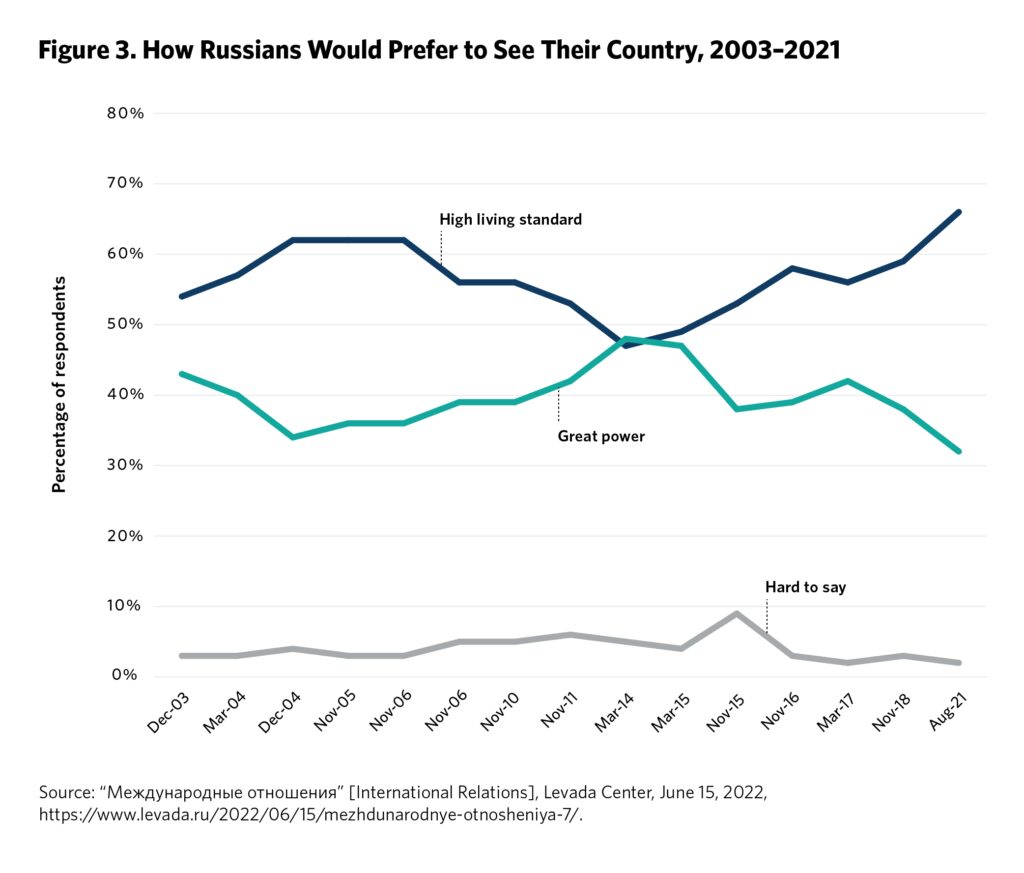

Since 2003, the Levada Center has asked Russians the binary question of whether they would prefer to see Russia be “a country with a high standard of living, even if not one of the most powerful countries in the world” or “a great power that is respected and feared by other countries.”52 In March 2014, the month in which Russia annexed Crimea, there was a roughly equal split in views: 47 percent of respondents said they would prefer to have a high standard of living, and 48 percent chose the great-power option. In August 2021, six months before the invasion of Ukraine, the proportion who favored a good living standard had reached a historic high of 66 percent, against 32 percent who preferred great-power status (see figure 3).

These findings point to the emergence of what might be called a postimperial Navalny constituency in Russian society: a younger, more globalized, mainly urban segment of the population that was growing year on year and wanted Russia to be a postimperial, normal country. If these trends had continued for another generation, they would have posed a threat to the Putin regime.

Russian exceptionalism and the threat of the West are useful weapons in this domestic battle. Political scientist Kirill Rogov has pointed out that Putin’s popularity has peaked roughly every seven years as a result of a military campaign: in 2000 after he launched the war in Chechnya, in 2008 with the war in Georgia, and in 2015 after the annexation of Crimea. In each case, his ratings declined after cresting a wave.

An even bigger foreign military adventure in 2022 enabled Putin to silence dissenting voices or force them into exile to rally the population around the flag and reconsolidate public support, which, the regime feared, was gradually dissipating. By making the war in Ukraine an existential issue for Russia and, by implication, his own regime, Putin was thereby also seeking to save himself.

Elite Compacts

If the need for regime survival is key to Putin’s aggression in Ukraine, it casts Russia’s relations with its other post-Soviet neighbors in a more instrumentalist light. Regime type and elites’ Soviet backgrounds are fairly good predictors of whether Moscow still deems a country to be a reliable partner.

Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan are one-party states. Many of their leaders are either former Soviet cadres or of an age that they were raised and educated in the Soviet Union. Ilham Aliyev, the president of Azerbaijan, and Tokayev are both graduates of elite Moscow universities.

Since the war in Ukraine, these leaders have adopted a two-prong survival strategy. They have reduced their security dependence on Russia and asked for and received international legitimation of their countries’ sovereignty. At the same time, they have looked to forge elite-to-elite compacts with Moscow that provide guarantees of regime preservation. It is indicative that while Russia did not intervene in Central Asia in 2010 or 2022 when interethnic conflict was costing lives, it did intervene in Kazakhstan in January 2022 to support Tokayev’s rule there.

Autocratic leaders seem to know where Russia’s redlines are. Institutional collaboration with the EU or NATO—as opposed to ad hoc partnerships on certain issues—seems to be one limit not to be crossed. Another demand is that leaders demonstrate respect for the Russian language—not so hard when they are all fluent Russian speakers. Thus, Aliyev makes the fact that there are more than 300 Russian-language schools in Azerbaijan a regular talking point with his Russian counterpart and told Putin in 2022 that the Russian language is “a very important basis of our relations and future ties.”53 Tokayev made headlines in November 2023 by speaking Kazakh, not Russian, at a public meeting with Putin.54 A month earlier, however, an intergovernmental meeting in Kyrgyzstan inaugurated the International Organization for the Russian Language, which Tokayev had personally promoted.55

These autocratic leaders share with the Putin regime a fear of a variation of the Arab Spring revolts that began in 2010 or a color revolution, a popular democratic uprising supported by Western pro-democracy nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Elites use the name “Soros”—in reference to billionaire philanthropist George Soros—as a shorthand for Western-inspired regime change or the instigation of disorder, even in democratic Georgia or countries where Soros’s Open Society Foundations were long ago forced to shut down their activities, such as Uzbekistan.56

Aliyev spelled this fear out at length in a February 2022 speech to a youth forum in Baku. He warned young people that they were the targets of “globalists, or I provisionally call them ‘Sorosians,’ [with] a destructive mission—to stir up the youth against their state.” Aliyev listed Western NGOs, among them Amnesty International and Freedom House, and media outlets, such as the New York Times and the Washington Post, which, he said, had plotted to depose him. “And in all of them Armenians play a leading role,” he added. Aliyev went on to name “Soros and the organizations he controls.”57

In countering these threats, whether real or imagined, it is easy for these autocratic rulers to find common cause with Russia, which will never criticize the conduct of elections and—as long as the regimes do not cross Moscow’s redlines—will not foment regime change.

Contrast this approach with Russia’s relations with the leaders of Armenia, Moldova, and Ukraine—Nikol Pashinyan, Maia Sandu, and Volodymyr Zelensky—who were all born in the 1970s, too late to be adults in the Soviet Union; received a different education; have a different outlook on the world; and have few or no connections in Russia. Having been democratically elected, these three base their legitimacy on a European-style people’s mandate.

Both Pashinyan and Sandu are making bids to emancipate their countries from their dependence on Russia and are turning to the EU and the United States for support. Despite many similarities in terms of size, income level, and democratic standards, Moldova is in a more advantageous position than Armenia in this regard thanks to its geographic location adjacent to the EU. In response, Russia uses a range of instruments, from intervening in domestic politics to threatening to raise the price of its gas exports.

In trying to tilt both Armenia and Moldova back toward Russia and away from the West, the Russian government faces a dilemma, however. As public opinion in both countries is increasingly negative toward Russia, punitive measures, such as restricting trade or raising Armenia’s gas price, risk further alienating the public and delivering a message of Russian power that may only play to the advantage of pro-Western politicians.

Georgia forms a strange hybrid case that belongs to neither of these two groups. The country is formally committed under its constitution to join the EU and NATO, and much of its professional elite is post-Soviet and Western educated. However, either from a fear of Russia or in collusion with it—or, perhaps, both—the governing Georgian Dream party has conspicuously failed to offer public support to Ukraine since 2022, and its political-business elite keeps many informal links with Russia. These maneuvers enabled the Georgian government to pull off the remarkable feat in 2023 of both moving closer to Russia and being granted candidate country status by the EU. In 2024, that balancing act was failing: by cracking down on dissent and pro-European protestors, the Georgian government seemed to prioritize the quiet approval of Russia over the objections of Western countries.

Multiple Neighborhoods

Geography is a crucial factor in the calculations of leaders who are recalibrating their relations with Russia. More than thirty years after the end of the Soviet Union, despite the continued assumptions of the Russian elite—and, occasionally, some Western headline writers who should know better—in labeling them “Russia’s backyard,” all of these countries can be said to live in multiple neighborhoods. History has returned over the last three decades, so that neighboring powers, such as China, Turkey, Romania, and Poland, are now as influential as, or sometimes more influential than, Russia.

In Central Asia, China is the other main actor. The countries in the region can hedge by building relations with Beijing, but Russia’s relationship with China is not necessarily adversarial. Experts on Central Asia caution against the notion that Beijing and Moscow are in conflict there. Alexander Gabuev and Temur Umarov have written that the two powers’ economic interests in the region are complementary and that “Moscow has come to view China’s gradually growing security presence not as a competitive challenge but as an opportunity for burden sharing.”58

In this context, the South Caucasus is once again what it has been for much of its history: a geopolitical crossroads where no one outside power has decisive influence. Throughout the region, Russia vies for influence with the EU, China, and Turkey. Moscow has acknowledged the emergence of Azerbaijan as the most powerful actor in the South Caucasus. Russia and Azerbaijan signed a partnership agreement in February 2022 shortly before the war in Ukraine began, but the accord is less significant to Baku than is Azerbaijan’s strong alliance with Turkey, which was confirmed in a treaty signed in 2021.

Russia now bids to be a less formal third member in this strong Azerbaijan-Turkey axis. Moscow and Ankara have a centuries-old history of contestation in the region, but they also have shared interests. With the South Caucasian trio, Russia, Turkey, and Iran have invested in a new regional 3+3 format, through which all three can pursue an agenda to limit Western influence in the region.59 Political scientist Seçkin Köstem has called their relationship “managed regional rivalry.”60

The EU is also a player in the neighborhood. In 2022–2023, Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia were given an EU membership perspective through candidate country status, something that would have been almost unthinkable before the war in Ukraine. There is even talk of Armenia being given such a perspective. In 2023, the EU deployed its first ever civilian monitoring mission to Armenia, a country that is a former Russian military ally.

The EU is challenging Russian energy monopolies, too. The war in Ukraine has seen the coming of age of the EU’s Energy Community, an organization in force since 2006 in which Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine are members and Armenia is an observer. The community was founded with the explicit intention to gradually extend the body of EU law on energy, the environment, and climate to participating countries.61 In 2022, the EU had the instruments in place to help both Moldova and Ukraine begin fairly rapidly to shed their dependence on Russian gas. Armenia and Georgia are more vulnerable in this regard, with Armenia still depending on Russia for around 85 percent of its gas, which is shipped via Georgia.62

Contestation over energy and transportation routes between the EU and Russia has intensified in the countries in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. Kazakhstan is vulnerable to Russia in that its main oil export route, the Caspian Pipeline Consortium, which exports 79 percent of the country’s main asset—crude oil—runs through Russian territory, and Russia has demonstrated since 2022 that it is prepared to shut the pipeline down.63 Rerouting oil across the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan is expensive and logistically challenging.

Azerbaijan and Georgia are better positioned and have used the post-2022 international environment to benefit economically from both Russia and Europe. In 2023, Azerbaijan struck a deal with the European Commission to double its gas exports to the EU by 2030 as Baku sought to wean itself off its dependence on Russian gas. It was a pledge that energy experts subsequently described as very difficult to meet but that earned Aliyev the compliment from European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen that Azerbaijan was a “crucial partner.”64

Simultaneously, Azerbaijan continued to work with Russia. In the winter of 2022–2023, Russian energy giant Gazprom sold gas to Azerbaijan to make up for shortfalls in Azerbaijani supply. In October 2023, Russian oil company Lukoil struck an agreement with Azerbaijan’s state oil and gas company, SOCAR, under which Lukoil lent the Azerbaijani firm $1.5 billion and pledged to supply SOCAR’s STAR oil refinery in Turkey with up to 200,000 barrels per day of Russian crude oil.65

Russia badly needs new transportation and connectivity routes. With Western trade links cut off, routes south into the South Caucasus, east into Central Asia, and onward to the Middle East and the rest of Asia have become much more important. Ruslan Davydov, the head of the Russian Customs Service, said in October 2023, “The main challenge for our customs service was to support the economy to withstand sanctions and facilitate a global pivot of our external trade from the west to the east and south.”66

Meanwhile, the Georgian government has exploited this situation to renew flights to and increase trade with Russia—to the frustration of Georgia’s Western partners. And rail traffic through Azerbaijan has increased such that in March 2024, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin said that volumes through the Russia-Azerbaijan border crossing had increased fivefold.67 These examples are part of a wider picture in which Russia’s southern and eastern post-Soviet neighbors are benefiting from doing business with both Russia and the West.

A Wartime Economy Brings Neighbors Closer

Conflict in Ukraine has reshaped the economic relationships between Russia and its neighbors to their advantage. While frontline states have reasons to be more fearful of Russia in 2024 than before, they are also benefiting economically from a situation in which they are exempt from Western sanctions and have therefore become key states for trade and reexport to Russia.

In this context, the EAEU has been given an unexpected new lease on life. Russia’s geopolitical and business interests converged in the creation of an economic union in which the country was responsible for 87 percent of the organization’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 and which precluded the other member states—Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan—from signing free-trade agreements with other trading blocs, such as the EU.68 In return, the other states received low trade tariffs, free movement of labor, and other economic inducements, including a low gas price from Moscow.

Armenia was both a key battleground and an example to others in Russia’s efforts to create a privileged economic space in the near abroad. In the 2000s, Russia had acquired almost all of Armenia’s main economic resources. Despite this, in 2013, then Armenian president Serzh Sargsyan was on the verge of signing an Association Agreement with the EU that included a large trade component, a Deep and Comprehensive Free-Trade Area. This accord would inevitably have reduced Russia’s grip on the Armenian economy. Then, two years of work with the EU were abruptly abandoned as Sargsyan announced that he would join Russia’s EAEU instead. Sargsyan barely hid the fact that he did so under coercion from Moscow, saying that Armenia’s core security interests were at stake.69

A much bigger prize eluded Russia in 2013, however, in Ukraine. Then Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych was also negotiating an EU Association Agreement. But unlike in Armenia, his decision to backtrack from the agreement triggered popular protests, which became known as the Euromaidan and eventually led to his downfall. At the time, Putin cited Ukraine’s potential NATO membership as a reason for threatening the country and seizing Crimea. In fact, NATO membership for Ukraine was not an imminent prospect. The huge economic impact of the conflict that followed—the billions of dollars of missed opportunities that Russian businesses suffered in Ukraine when the country failed to join the EAEU in 2013—is often overlooked.70

Immediately after Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the EAEU looked unfit for purpose. In March, Russia unilaterally announced a ban on exports of grain and sugar to other EAEU member states—a drastic measure that it later softened.71 Subsequently, the picture changed as Russia looked to neighboring countries to help it overcome its new isolation. The EAEU as well as the CIS were refashioned as more informal deal-making organizations. A May 2023 leaders’ meeting in Moscow drew a strong turnout, being attended not only by the EAEU leaders but also by the president of Azerbaijan in person and the presidents of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan online.72

The countries in the South Caucasus and Central Asia have all enjoyed an economic boom as a result of the war in Ukraine. Reexports of goods to Russia, including dual-use goods that could be adapted for military purposes, have burgeoned. For example, Kyrgyzstan has reported a massive increase in car imports from various countries since 2022, including a 5,500 percent increase in imports of German cars and vehicle parts—presumably for reexport to Russia.73 The three countries in the South Caucasus have all registered similar dramatic rises in imports of European cars.74

As a result, Armenia’s GDP in 2024 is close to double what it was in 2021, having risen from $13.8 billion to $26.9 billion according to calculations by the International Monetary Fund.75 Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan have all recorded healthy levels of economic growth. South Caucasian and Central Asian countries have also benefited economically from an influx of educated Russians, many of them relocating their businesses. Armenia and Kazakhstan were especially attractive destinations as migrants could maintain their bank cards and transactions with Russia under EAEU rules. In parallel, Central Asian migrant workers were needed more than ever in Russia to fill the jobs left by departing Russians and young men called up into the army.

These increased business links, many of which exploit loopholes or gaps in Western sanctions policies, have empowered middlemen, who are often ethnic nationals of South Caucasian or Central Asian countries and resident in Russia. One of them is former Georgian general prosecutor Otar Partskhaladze, who was sanctioned by the United States in September 2023 along with business associates who are close to both Russian elite circles and the Georgian Dream government.76 Another such middleman is Armenian-Russian tycoon Samvel Karapetyan, whose Tashir Group works closely with Gazprom and owns major energy assets in Armenia.77

The group of elite Russian-Azerbaijanis who act as trusted intermediaries between Moscow and Baku is even more numerous. One prominent figure is God Nisanov, most famous for owning the Ukraine Hotel and the massive Food City produce markets. He is said to be friends with Russian foreign intelligence chief Sergei Naryshkin and close to Aliyev and his family.78

Western sanctions on Russian oil and gas have also been a boon for so-called petro-elites, who work between Russia, Central Asia, and Azerbaijan. Even before the war in Ukraine, Russia expert Morena Skalamera wrote that there was a shared interest among the Eurasian petro-economies in cooperating to perpetuate revenues for the elites and resist a shift away from fossil fuels: “In Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, most natural resources and heavy industries remain controlled by an oligarchy of neftyaniki [oilmen] that still wields strong political influence and retains close business ties with Russian elites and insiders.”79

For example, Uzbekistan is set to increase its imports of Russian gas, and cooperation with Russian energy companies has intensified.80 In Kazakhstan, Moscow’s relations with the regime and family of former president Nursultan Nazarbayev were close until they fell out of favor in 2022. Under the Tokayev administration, Kazakh-Russian “energy interdependence is growing,” wrote political risk expert Kate Mallinson, while his government has struck several deals with Russia for uranium and coal.81

Azerbaijan’s petro-elite works more closely with Western companies but still keeps many connections with Russia. Senior Azerbaijani oil and gas managers who are Russian citizens include Gazprom’s Famil Sadygov and Lukoil’s Vagit Alekperov. According to a Wall Street Journal investigation, after Western companies withdrew from Russia following its invasion of Ukraine, Russian oil company Rosneft’s oil trade was taken over by a group of Russian Azerbaijanis operating out of Dubai and Hong Kong.82 Given that petro-elites are close to or indistinguishable from political elites, it is likely that most or all of these business deals were negotiated at the highest level.

The increased economic cooperation between Russia and its neighbors is lucrative—but also fragile and contingent on international political developments. New rounds of Western sanctions could threaten the livelihoods of Eurasian middlemen or shut down certain types of trade with Russia. A downturn in the Russian economy could very negatively affect migrant workers in Russia and Russian professional migrants in countries such as Armenia and Kazakhstan. In other words, a fresh crisis and a new round of bargaining between Moscow and its neighbors are possible at any moment.

Conclusion

Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 made all of its other neighbors feel deeply insecure. The decision to attack a sovereign state, accompanied by a menacing neo-imperialist discourse from Russian officials and commentators, sent the other post-Soviet states the message that they also belonged to a sphere of Russian influence and had no right to determine their own futures.

The war has simultaneously made Russia more threatening, weaker, and more unpredictable. In 2022, Russia intervened militarily in Ukraine yet also declined to do so in two disputes in Central Asia and the South Caucasus. Pressed by a host of day-to-day preoccupations, the Putin regime no longer pretends to have an overarching regional security strategy. Instead, with multilateral organizations such as the UN and the OSCE also weaker, the trend is toward an ad hoc regionalization of security arrangements as other regional powers, such as China, Iran, and Turkey, assert their interests and may seek to cut deals with Russia over the heads of the countries concerned. It is more a gangland environment than a post-Russia order.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine marked the end of three decades of softer Russian post-Soviet integration projects, which were encapsulated in the term “near abroad.” One reason why Putin resorted to mass violence is because his integration projects to create a Russia-centered belt of states had not worked out as planned.

The invasion was not inevitable. Much of Russia’s elite is afflicted by an imperial mindset, but the country’s personalized autocracy is arguably more consequential. During Russia’s first two post-Soviet decades, other more conciliatory options on how to engage with its neighborhood had been part of the mainstream political discourse. Putin’s war was intended to legitimize his own autocratic rule by extinguishing alternative visions of a postimperial Russia, which would have promised more freedom not only for Russia’s neighbors but also for Russian citizens.

In a highly uncertain environment and a potential security vacuum, the other post-Soviet states continue to do political and economic deals with Russia. Economic cooperation between the South Caucasus and Central Asian states, on the one hand, and Moscow, on the other, has increased in the past two years, as these countries provide alternative trade routes for Russia, which suffers from a Western economic blockade. Their economies have all grown since 2022.

To use the language of political science, regime type matters. The one-party autocratic governments in Central Asia and Azerbaijan have adapted best to the volatile post-2022 situation. A long Soviet legacy is no less palpable there than in Russia. The leaders of these countries have made their republics bastions of sovereignty and are generally averse to power sharing not only within their societies but also with their regional neighbors.

These leaders have reached out to Western governments and received new attention from them. That attention is warranted. Yet, most of these leaders are cut from the same Soviet cloth as the Russian elite, and their regimes bear a strong resemblance to Putin’s. They have studied or worked in Russia and speak the same language as the Putin regime, both literally and figuratively. Their petro-elites continue to do oil and gas deals with Russian companies. While also reaching out to Western powers and China, these leaders let the Putin regime understand that they will not cross Russian redlines by embracing democracy or seeking EU or NATO membership. In this respect, the leaders are often out of step with their societies, where the mood of alienation from Russia is stronger.

With these one-party states, European actors should pursue policies that reinforce their sovereignty and enable them to decrease their dependence on Russia. But Europeans should be careful in the process not to strengthen undemocratic elites who still work closely with Moscow and are instrumentalizing Russia’s war in Ukraine to their advantage.

Three other countries—Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova—have many differences but share the fact that they are democracies and more vulnerable to Russia. There, Western actors have more opportunities to provide direct security assistance, work with societies, and strengthen democratic institutions. But this is likely to be successful only if there is seen to be evidence of a serious long-term commitment. EU accession promises this, but the way ahead is not so clear to many citizens. These three countries also have divided societies, and it is important to engage with those constituencies that, for economic, cultural, or religious reasons, are still linked to Russia.

For the foreseeable future, Russia’s neighbors can only expect the unexpected. This is especially true as all consequential decisions are being made by one man—Putin—and any checks and balances have been removed. If the Russian leader decides to take action in the near abroad, however unwise other state actors in Russia deem it to be, there is very little to stop him. Dealing with the threats and uncertainties that the new Russia presents requires from others both short-term agility and a long-term investment of resources.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News