Surviving a World Gone Gray

Although few yet see it coming, humans are about to enter a new era of history. Call it “the age of depopulation.” For the first time since the Black Death in the 1300s, the planetary population will decline. But whereas the last implosion was caused by a deadly disease borne by fleas, the coming one will be entirely due to choices made by people.

With birthrates plummeting, more and more societies are heading into an era of pervasive and indefinite depopulation, one that will eventually encompass the whole planet. What lies ahead is a world made up of shrinking and aging societies. Net mortality—when a society experiences more deaths than births—will likewise become the new norm. Driven by an unrelenting collapse in fertility, family structures and living arrangements heretofore imagined only in science fiction novels will become commonplace, unremarkable features of everyday life.

Human beings have no collective memory of depopulation. Overall global numbers last declined about 700 years ago, in the wake of the bubonic plague that tore through much of Eurasia. In the following seven centuries, the world’s population surged almost 20-fold. And just over the past century, the human population has quadrupled.

The last global depopulation was reversed by procreative power once the Black Death ran its course. This time around, a dearth of procreative power is the cause of humanity’s dwindling numbers, a first in the history of the species. A revolutionary force drives the impending depopulation: a worldwide reduction in the desire for children.

So far, government attempts to incentivize childbearing have failed to bring fertility rates back to replacement levels. Future government policy, regardless of its ambition, will not stave off depopulation. The shrinking of the world’s population is all but inevitable. Societies will have fewer workers, entrepreneurs, and innovators—and more people dependent on care and assistance. The problems this dynamic raises, however, are not necessarily tantamount to a catastrophe. Depopulation is not a grave sentence; rather, it is a difficult new context, one in which countries can still find ways to thrive. Governments must prepare their societies now to meet the social and economic challenges of an aging and depopulating world.

In the United States and elsewhere, thinkers and policymakers are not ready for this new demographic order. Most people cannot comprehend the coming changes or imagine how prolonged depopulation will recast societies, economies, and power politics. But it is not too late for leaders to reckon with the seemingly unstoppable force of depopulation and help their countries succeed in a world gone gray.

A SPIN OF THE GLOBE

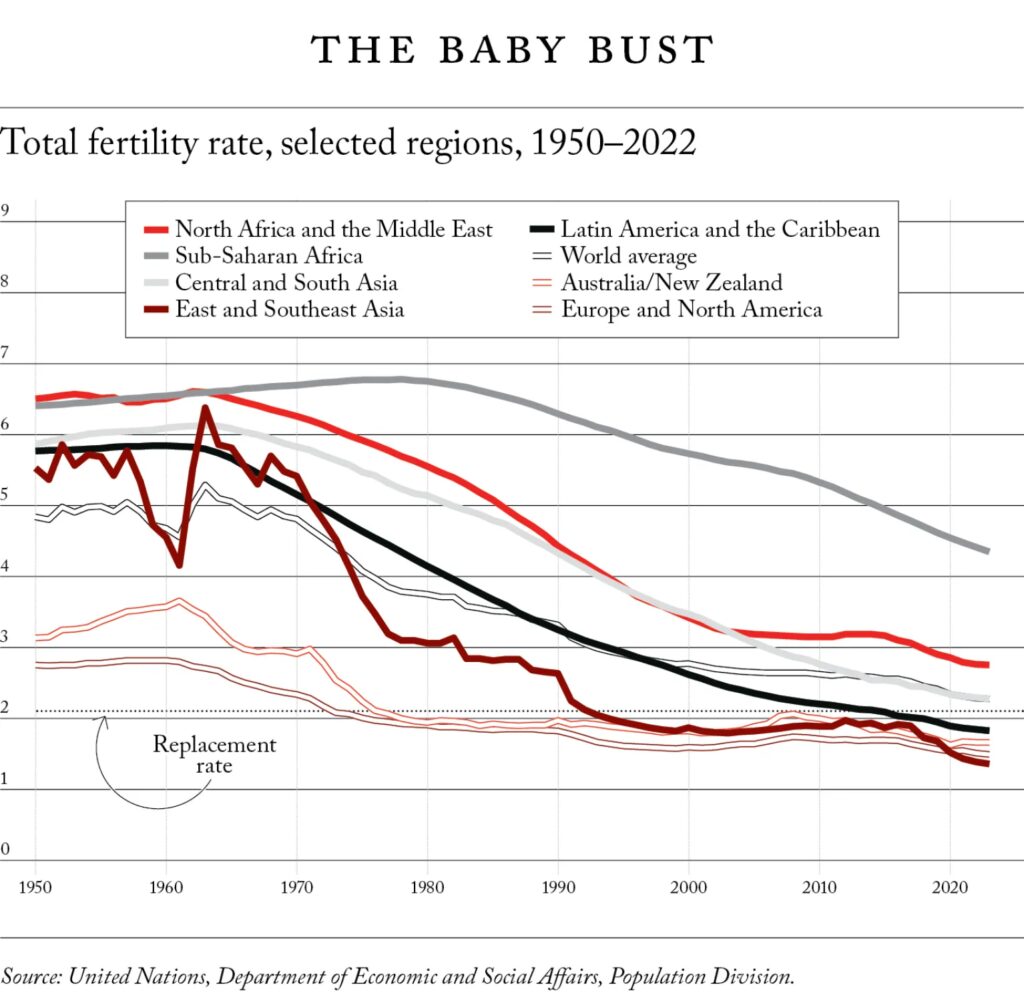

Global fertility has plunged since the population explosion in the 1960s. For over two generations, the world’s average childbearing levels have headed relentlessly downward, as one country after another joined in the decline. According to the UN Population Division, the total fertility rate for the planet was only half as high in 2015 as it was in 1965. By the UNPD’s reckoning, every country saw birthrates drop over that period.

And the downswing in fertility just kept going. Today, the great majority of the world’s people live in countries with below-replacement fertility levels, patterns inherently incapable of sustaining long-term population stability. (As a rule of thumb, a total fertility rate of 2.1 births per woman approximates the replacement threshold in affluent countries with high life expectancy—but the replacement level is somewhat higher in countries with lower life expectancy or marked imbalances in the ratio of baby boys to baby girls.)

In recent years, the birth plunge has not only continued but also seemingly quickened. According to the UNPD, at least two-thirds of the world’s population lived in sub-replacement countries in 2019, on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic. The economist Jesús Fernández-Villaverde has contended that the overall global fertility rate may have dropped below the replacement level since then. Rich and poor countries alike have witnessed record-breaking, jaw-dropping collapses in fertility. A quick spin of the globe offers a startling picture.

Start with East Asia. The UNPD has reported that the entire region tipped into depopulation in 2021. By 2022, every major population there—in China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—was shrinking. By 2023, fertility levels were 40 percent below replacement in Japan, over 50 percent below replacement in China, almost 60 percent below replacement in Taiwan, and an astonishing 65 percent below replacement in South Korea.

As for Southeast Asia, the UNPD has estimated that the region as a whole fell below the replacement level around 2018. Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam have been sub-replacement countries for years. Indonesia, the fourth most populous country in the world, joined the sub-replacement club in 2022, according to official figures. The Philippines now reports just 1.9 births per woman. The birthrate of impoverished, war-riven Myanmar is below replacement, too. In Thailand, deaths now exceed births and the population is declining.

In South Asia, sub-replacement fertility prevails not only in India—now the world’s most populous country—but also in Nepal and Sri Lanka; all three dropped below replacement before the pandemic. (Bangladesh is on the verge of falling below the replacement threshold.) In India, urban fertility levels have dropped markedly. In the vast metropolis of Kolkata, for instance, state health officials reported in 2021 that the fertility rate was down to an amazing one birth per woman, less than half the replacement level and lower than in any major city in Germany or Italy.

Dramatic declines are also sweeping Latin America and the Caribbean. The UNPD has calculated overall fertility for the region in 2024 at 1.8 births per woman—14 percent below the replacement rate. But that projection may understate the actual decline, given what the Costa Rican demographer Luis Rosero-Bixby has described as the “vertiginous” drop in birthrates in the region since 2015. In his country, total fertility rates are now down to 1.2 births per woman. Cuba reported a 2023 fertility rate of just over 1.1, half the replacement rate; since 2019, deaths there have exceeded births. Uruguay’s rate was close to 1.3 in 2023 and, as in Cuba, deaths exceeded births. In Chile, the figure in 2023 was just over 1.1 births per woman. Major Latin American cities, including Bogota and Mexico City, now report rates below one birth per woman.

Sub-replacement fertility has even come to North Africa and the greater Middle East, where demographers have long assumed that the Islamic faith served as a bulwark against precipitous fertility declines. Despite the pro-natal philosophy of its theocratic rulers, Iran has been a sub-replacement society for about a quarter century. Tunisia has also dipped below replacement. In sub-replacement Turkey, Istanbul’s 2023 birthrate was just 1.2 babies per woman—lower than Berlin’s.

Global fertility has plunged since the population explosion in the 1960s.

For half a century, Europe’s overall fertility rates have been continuously sub-replacement. Russian fertility first dropped below replacement in the 1960s, during the Brezhnev era, and since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia has witnessed 17 million more deaths than births. Like Russia, the 27 countries of the current European Union are about 30 percent below replacement today. Together, they reported just under 3.7 million births in 2023—down from 6.8 million in 1964. Last year, France tallied fewer births than it did in 1806, the year Napoleon won the Battle of Jena; Italy reported the fewest births since its 1861 reunification; and Spain the fewest since 1859, when it started to compile modern birth figures. Poland had its fewest births in the postwar era in 2023; so did Germany. The EU has been a net-mortality zone since 2012, and in 2022 it registered four deaths for every three births. The UNPD has marked 2019 as the peak year for Europe’s population and has estimated that in 2020, the continent entered what will become a long-term population decline.

The United States remains the main outlier among developed countries, resisting the trend of depopulation. With relatively high fertility levels for a rich country (although far below replacement—just over 1.6 births per woman in 2023) and steady inflows of immigrants, the United States has exhibited what I termed in these pages in 2019 “American demographic exceptionalism.” But even in the United States, depopulation is no longer unthinkable. Last year, the Census Bureau projected that the U.S. population would peak around 2080 and head into a continuous decline thereafter.

The only major remaining bastion against the global wave of sub-replacement levels of childbearing is sub-Saharan Africa. With its roughly 1.2 billion people and a UNPD-projected average fertility rate of 4.3 births per woman today, the region is the planet’s last consequential redoubt of the fertility patterns that characterized low-income countries during the population explosion of the middle half of the twentieth century.

But even there, rates are dropping. The UNPD has estimated that fertility levels in sub-Saharan Africa have fallen by over 35 percent since the late 1970s, when the subcontinent’s overall level was an astonishing 6.8 births per woman. In South Africa, birth levels appear to be just fractionally above replacement, with other countries in southern Africa close behind. A number of island countries off the African coast, including Cape Verde and Mauritius, are already sub-replacement.

The UNPD has estimated that the replacement threshold for the world as a whole is roughly 2.18 births per woman. Its latest medium variant projections—roughly, the median of projected outcomes—for 2024 have put global fertility at just three percent above replacement, and its low variant projections—the lower end of projected outcomes—have estimated that the planet is already eight percent below that level. It is possible that humanity has dropped below the planetary net-replacement rate already. What is certain, however, is that for a quarter of the world, population decline is already underway, and the rest of the world is on course to follow those pioneers into the depopulation that lies ahead.

THE POWER OF CHOICE

The worldwide plunge in fertility levels is still in many ways a mystery. It is generally believed that economic growth and material progress—what scholars often call “development” or “modernization”—account for the world’s slide into super-low birthrates and national population decline. Since birthrate declines commenced with the socioeconomic rise of the West—and since the planet is becoming ever richer, healthier, more educated, and more urbanized—many observers presume lower birthrates are simply the direct consequence of material advances.

But the truth is that developmental thresholds for below-replacement fertility have been falling over time. Nowadays, countries can veer into sub-replacement with low incomes, limited levels of education, little urbanization, and extreme poverty. Myanmar and Nepal are impoverished UN-designated Least Developed Countries, but they are now also sub-replacement societies.

During the postwar period, a veritable library of research has been published on factors that might explain the decline in fertility that picked up pace in the twentieth century. Drops in infant mortality rates, greater access to modern contraception, higher rates of education and literacy, increases in female labor-force participation and the status of women—all these potential determinants and many more were extensively scrutinized by scholars. But stubborn real-life exceptions always prevented the formation of any ironclad socioeconomic generalization about fertility decline.

Eventually, in 1994, the economist Lant Pritchett discovered the most powerful national fertility predictor ever detected. That decisive factor turned out to be simple: what women want. Because survey data conventionally focus on female fertility preferences, not those of their husbands or partners, scholars know much more about women’s desire for children than men’s. Pritchett determined that there is an almost one-to-one correspondence around the world between national fertility levels and the number of babies women say they want to have. This finding underscored the central role of volition—of human agency—in fertility patterns.

But if volition shapes birthrates, what explains the sudden worldwide dive into sub-replacement territory? Why, in rich and poor countries alike, are families with a single child, or no children at all, suddenly becoming so much more common? Scholars have not yet been able to answer that question. But in the absence of a definitive answer, a few observations and speculations will have to suffice.

It is apparent, for example, that a revolution in the family—in family formation, not just in childbearing—is underway in societies around the world. This is true in rich countries and poor ones, across cultural traditions and value systems. Signs of this revolution include what researchers call the “flight from marriage,” with people getting married at later ages or not at all; the spread of nonmarital cohabitation and temporary unions; and the increase in homes in which one person lives independently—in other words, alone. These new arrangements track with the emergence of below-replacement fertility in societies around the globe—not perfectly, but well enough.

It is striking that these revealed preferences have so quickly become prevalent on almost every continent. People the world over are now aware of the possibility of very different ways of life from the ones that confined their parents. Certainly, religious belief—which generally encourages marriage and celebrates child rearing—seems to be on the wane in many regions where birthrates are crashing. Conversely, people increasingly prize autonomy, self-actualization, and convenience. And children, for their many joys, are quintessentially inconvenient.

Population trends today should raise serious questions about all the old nostrums that humans are somehow hard-wired to replace themselves to continue the species. Indeed, what is happening might be better explained by the field of mimetic theory, which recognizes that imitation can drive decisions, stressing the role of volition and social learning in human arrangements. Many women (and men) may be less keen to have children because so many others are having fewer children. The increasing rarity of large families could make it harder for humans to choose to return to having them—owing to what scholars call loss of “social learning”—and prolong low levels of fertility. Volition is why, even in an increasingly healthy and prosperous world of over eight billion people, the extinction of every family line could be only one generation away.

COUNTRIES FOR OLD MEN

The consensus among demographic authorities today is that the global population will peak later this century and then start to decline. Some estimates suggest that this might happen as soon as 2053, others as late as the 2070s or 2080s.

Regardless of when this turn commences, a depopulated future will differ sharply from the present. Low fertility rates mean that annual deaths will exceed annual births in more countries and by widening margins over the coming generation. According to some projections, by 2050, over 130 countries across the planet will be part of the growing net-mortality zone—an area encompassing about five-eighths of the world’s projected population. Net-mortality countries will emerge in sub-Saharan Africa by 2050, starting with South Africa. Once a society has entered net mortality, only continued and ever-increasing immigration can stave off long-term population decline.

Future labor forces will shrink around the world because of the spread of sub-replacement birthrates today. By 2040, national cohorts of people between the ages of 15 and 49 will decrease more or less everywhere outside sub-Saharan Africa. That group is already shrinking in the West and in East Asia. It is set to start dropping in Latin America by 2033 and will do so just a few years later in Southeast Asia (2034), India (2036), and Bangladesh (2043). By 2050, two-thirds of people around the world could see working-age populations (people between the ages of 20 and 64) diminish in their countries—a trend that stands to constrain economic potential in those countries in the absence of innovative adjustments and countermeasures.

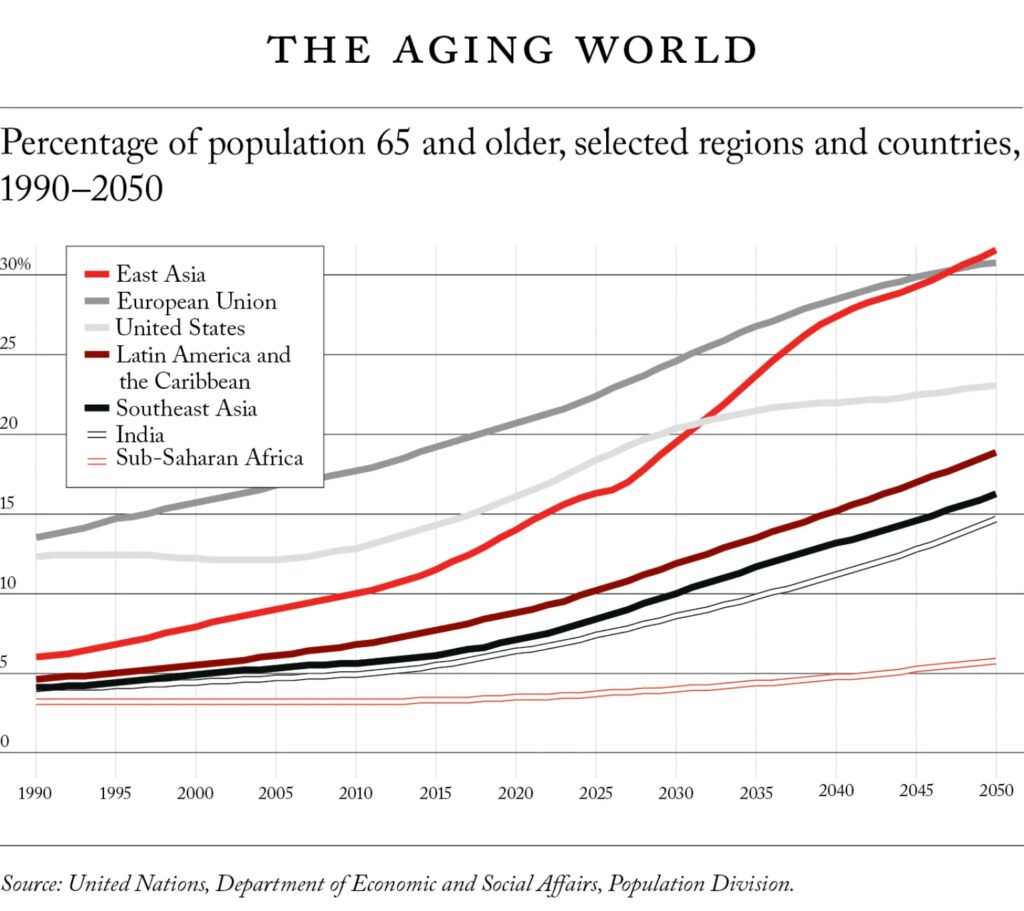

A depopulating world will be an aging one. Across the globe, the march to low fertility, and now to super-low birthrates, is creating top-heavy population pyramids, in which the old begin to outnumber the young. Over the coming generation, aged societies will become the norm.

Policymakers are not ready for the coming demographic order.

By 2040—except, once again, in sub-Saharan Africa—the number of people under the age of 50 will decline. By 2050, there will be hundreds of millions fewer people under the age of 60 outside sub-Saharan Africa than there are today—some 13 percent fewer, according to several UNPD projections. At the same time, the number of people who are 65 or older will be exploding: a consequence of relatively high birthrates back in the late twentieth century and longer life expectancy.

While the overall population growth slumps, the number of seniors (defined here as people aged 65 or older) will surge exponentially—everywhere. Outside Africa, that group will double in size to 1.4 billion by 2050. The upsurge in the 80-plus population—the “super-old”—will be even more rapid. That contingent will nearly triple in the non-African world, leaping to roughly 425 million by 2050. Just over two decades ago, fewer than 425 million people on the planet had even reached their 65th birthday.

The shape of things to come is suggested by mind-bending projections for countries at the vanguard of tomorrow’s depopulation: places with abidingly low birthrates for over half a century and favorable life expectancy trends. South Korea provides the most stunning vision of a depopulating society just a generation away. Current projections have suggested that South Korea will mark three deaths for every birth by 2050. In some UNPD projections, the median age in South Korea will approach 60. More than 40 percent of the country’s population will be senior citizens; more than one in six South Koreans will be over the age of 80. South Korea will have just a fifth as many babies in 2050 as it did in 1961. It will have barely 1.2 working-age people for every senior citizen.

Should South Korea’s current fertility trends persist, the country’s population will continue to decline by over three percent per year—crashing by 95 percent over the course of a century. What is on track to happen in South Korea offers a foretaste of what lies in store for the rest of the world.

WAVE OF SENESCENCE

Depopulation will upend familiar social and economic rhythms. Societies will have to adjust their expectations to comport with the new realities of fewer workers, savers, taxpayers, renters, home buyers, entrepreneurs, innovators, inventors, and, eventually, consumers and voters. The pervasive graying of the population and protracted population decline will hobble economic growth and cripple social welfare systems in rich countries, threatening their very prospects for continued prosperity. Without sweeping changes in incentive structures, life-cycle earning and consumption patterns, and government policies for taxation and social expenditures, dwindling workforces, reduced savings and investment, unsustainable social outlays, and budget deficits are all in the cards for today’s developed countries.

Until this century, only affluent societies in the West and in East Asia had gone gray. But in the foreseeable future, many poorer countries will have to contend with the needs of an aged society even though their workers are far less productive than those in wealthier countries.

Consider Bangladesh: a poor country today that will be an elderly society tomorrow, with over 13 percent of its 2050 population projected to be seniors. The backbone of the Bangladeshi labor force in 2050 will be today’s youth. But standardized tests show that five in six members of this group fail to meet even the very lowest international skill standards deemed necessary for participation in a modern economy: the overwhelming majority of this rising cohort cannot “read and answer basic questions” or “add, subtract, and round whole numbers and decimals.” In 2020, Ireland was roughly as elderly as Bangladesh will be in 2050—but in Ireland nowadays, only one in six young people lacks such minimal skills.

The poor, elderly countries of the future may find themselves under great pressure to build welfare states before they can actually fund them. But income levels are likely to be decidedly lower in 2050 for many Asian, Latin American, Middle Eastern, and North African countries than they were in Western countries at the same stage of population graying—how can these countries achieve the adequate means to support and care for their elderly populations?

In rich and poor countries alike, a coming wave of senescence stands to impose completely unfamiliar burdens on many societies. Although people in their 60s and 70s may well lead economically active and financially self-reliant lives in the foreseeable future, the same is not true for those in their 80s or older. The super-old are the world’s fastest-growing cohort. By 2050, there will be more of them than children in some countries. The burden of caring for people with dementia will pose growing costs—human, social, economic—in an aging and shrinking world.

That burden will become all the more onerous as families wither. Families are society’s most basic unit and are still humanity’s most indispensable institution. Both precipitous aging and steep sub-replacement fertility are inextricably connected to the ongoing revolution in family structure. As familial units grow smaller and more atomized, fewer people get married, and high levels of voluntary childlessness take hold in country after country. As a result, families and their branches become ever less able to bear weight—even as the demands that might be placed on them steadily rise.

Just how depopulating societies will cope with this broad retreat of the family is by no means obvious. Perhaps others could step in to assume roles traditionally undertaken by blood relatives. But appeals to duty and sacrifice for those who are not kin may lack the strength of calls from within a family. Governments may try to fill the breach, but sad experience with a century and a half of social policy suggests that the state is a horrendously expensive substitute for the family—and not a very good one. Technological advances—robotics, artificial intelligence, human-like cyber-caregivers and cyber-“friends”—may eventually make some currently unfathomable contribution. But for now, that prospect belongs in the realm of science fiction, and even there, dystopia is far more likely than anything verging on utopia.

THE MAGIC FORMULA

This new chapter for humanity may seem ominous, perhaps frightening. But even in a graying and depopulating world, steadily improving living standards and material and technological advances will still be possible.

Just two generations ago, governments, pundits, and global institutions were panicking about a population explosion, fearing mass starvation and immiseration as a result of childbearing in poor countries. In hindsight, that panic was bizarrely overblown. The so-called population explosion was in reality a testament to increases in life expectancy owing to better public health practices and access to health care. Despite tremendous population growth in the last century, the planet is richer and better fed than ever before—and natural resources are more plentiful and less expensive (after adjusting for inflation) than ever before.

The same formula that spread prosperity during the twentieth century can ensure further advances in the twenty-first and beyond—even in a world marked by depopulation. The essence of modern economic development is the continuing augmentation of human potential and a propitious business climate, framed by policies and institutions that help unlock the value in human beings. With that formula, India, for instance, has virtually eliminated extreme poverty over the past half century. Improvements in health, education, and science and technology are fuel for the motor generating material advances. Irrespective of demographic aging and shrinking, societies can still benefit from progress across the board in these areas. The world has never been as extensively schooled as it is today, and there is no reason to expect the rise in training to stop, despite aging and shrinking populations, given the immense gains that accrue from education to both societies and the trainees themselves.

Remarkable improvements in health and education around the world speak to the application of scientific and social knowledge—the stock of which has been relentlessly advancing, thanks to human inquiry and innovation. That drive will not stop now. Even an elderly, depopulating world can grow increasingly affluent.

The lack of desire for children is why the extinction of every family line could be only one generation away.

Yet as the old population pyramid is turned on its head and societies assume new structures under long-term population decline, people will need to develop new habits of mind, conventions, and cooperative objectives. Policymakers will have to learn new rules for development amid depopulation. The basic formula for material advance—reaping the rewards of augmented human resources and technological innovation through a favorable business climate—will be the same. But the terrain of risk and opportunity facing societies and economies will change with depopulation. And in response, governments will have to adjust their policies to reckon with the new realities.

The initial transition to depopulation will no doubt entail painful, wrenching changes. In depopulating societies, today’s “pay-as-you-go” social programs for national pension and old-age health care will fail as the working population shrinks and the number of elderly claimants balloons. If today’s age-specific labor and spending patterns continue, graying and depopulating countries will lack the savings to invest for growth or even to replace old infrastructure and equipment. Current incentives, in short, are seriously misaligned for the advent of depopulation. But policy reforms and private-sector responses can hasten necessary adjustments.

To adapt successfully to a depopulating world, states, businesses, and individuals will have to place a premium on responsibility and savings. There will be less margin for error for investment projects, be they public or private, and no rising tide of demand from a growing pool of consumers or taxpayers to count on.

As people live longer and remain healthy into their advanced years, they will retire later. Voluntary economic activity at ever-older ages will make lifelong learning imperative. Artificial intelligence may be a double-edged sword in this regard: although AI may offer productivity improvements that depopulating societies could not otherwise manage, it could also hasten the displacement of those with inadequate or outdated skills. High unemployment could turn out to be a problem in shrinking, labor-scarce societies, too.

States and societies will have to ensure that labor markets are flexible—reducing barriers to entry, welcoming the job turnover and churn that boost dynamism, eliminating age discrimination, and more—given the urgency of increasing the productivity of a dwindling labor force. To foster economic growth, countries will need even greater scientific advances and technological innovation.

Prosperity in a depopulating world will also depend on open economies: free trade in goods, services, and finance to counter the constraints that declining populations otherwise engender. And as the hunger for scarce talent becomes more acute, the movement of people will take on new economic salience. In the shadow of depopulation, immigration will matter even more than it does today.

Not all aged societies, however, will be capable of assimilating young immigrants or turning them into loyal and productive citizens. And not all migrants will be capable of contributing effectively to receiving economies, especially given the stark lack of basic skills characterizing too many of the world’s rapidly growing populations today.

Pragmatic migration strategies will be of benefit to depopulating societies in the generations ahead—bolstering their labor forces, tax bases, and consumer spending while also rewarding the immigrants’ countries of origin with lucrative remittances. With populations shrinking, governments will have to compete for migrants, with an even greater premium placed on attracting talent from abroad. Getting competitive migration policies right—and securing public support for them—will be a major task for future governments but one well worth the effort.

THE GEOPOLITICS OF NUMBERS

Depopulation will not only transform how governments deal with their citizens; it will also transform how they deal with one another. Humanity’s shrinking ranks will inexorably alter the current global balance of power and strain the existing world order.

Some of the ways it will do so are relatively easy to foresee today. One of the demographic certainties about the generation ahead is that differentials in population growth will make for rapid shifts in the relative size of the world’s major regions. Tomorrow’s world will be much more African. Although about a seventh of the world’s population today lives in sub-Saharan Africa, the region accounts for nearly a third of all births; its share of the world’s workforce and population are thus set to grow immensely over the coming generation.

But this does not necessarily mean that an “African century” lies just ahead. In a world where per capita output varies by as much as a factor of 100 between countries, human capital—not just population totals—matters greatly to national power, and the outlook for human capital in sub-Saharan Africa remains disappointing. Standardized tests indicate that a stunning 94 percent of youth in the region lack even basic skills. As huge as the region’s 2050 pool of workers promises to be, the number of workers with basic skills may not be much larger there than it will be in Russia alone in 2050.

India is now the world’s most populous country and on track to continue to grow for at least another few decades. Its demographics virtually assure that the country will be a leading power in 2050. But India’s rise is compromised by human resource vulnerabilities. India has a world-class cadre of scientists, technicians, and elite graduates. But ordinary Indians receive poor education. A shocking seven out of eight young people in India today lack even basic skills—a consequence of both low enrollment and the generally poor quality of the primary and secondary schools available to those lucky enough to get schooling. The skills profile for China’s youth is decades, maybe generations, ahead of India’s youth today. India is unlikely to surpass a depopulating China in per capita output or even in total GDP for a very long time.

The coalescing partnership among China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia is intent on challenging the U.S.-led Western order. These revisionist countries have aggressive and ambitious leaders and are seemingly confident in their international objectives. But the demographic tides are against them.

A revolution in family formation is underway in societies around the world.

China and Russia are long-standing sub-replacement societies, both now with shrinking workforces and declining populations. Iran’s population is likewise far below replacement levels. Population data on North Korea remain secret, but the dictator Kim Jong Un’s very public worrying late last year about the national birthrate suggests the leadership is not happy about the country’s demographics.

Russia’s shrinking numbers and its seemingly intractable difficulties with public health and knowledge production have been reducing the country’s relative economic power for decades, with no turnaround in sight. China’s birth crash—the next generation is on track to be only half as large as the preceding one—will unavoidably slash the workforce and turbocharge population aging, even as the Chinese extended family, heretofore the country’s main social safety net, atrophies and disintegrates. These impending realities presage unimagined new social welfare burdens for a no longer dazzling Chinese economy and may end up hamstringing the funding for Beijing’s international ambitions.

To be sure, revisionist states with nuclear weapons can pose outsize risks to the existing global order—witness the trouble North Korea causes despite a negligible GDP. But the demographic foundations for national power are tilting against the renegades as their respective depopulations loom.

As for the United States, the demographic fundamentals look fairly sound—at least when compared with the competition. Demographic trends are on course to augment American power over the coming decades, lending support for continued U.S. global preeminence. Given the domestic tensions and social strains that Americans are living through today, these long-term American advantages may come as a surprise. But they are already beginning to be taken into account by observers and actors abroad.

Although the United States is a sub-replacement society, it has higher fertility levels than any East Asian country and almost all European states. In conjunction with strong immigrant inflows, the United States’ less anemic birth trends give the country a very different demographic trajectory from that of most other affluent Western societies, with continued population and labor-force growth and only moderate population aging in store through 2050.

Thanks in large measure to immigration, the United States is on track to account for a growing share of the rich world’s labor force, youth, and highly educated talent. Continuing inflows of skilled immigrants also give the country a great advantage. No other population on the planet is better placed to translate population potential into national power—and it looks as if that demographic edge will be at least as great in 2050. Compared with other contenders, U.S. demographics look great today—and may look even better tomorrow—pending, it must be underscored, continued public support for immigration. The United States remains the most important geopolitical exception to the coming depopulation.

But depopulation will also scramble the balance of power in unpredictable ways. Two unknowns stand out above all others: how swiftly and adeptly depopulating societies will adapt to their unfamiliar new circumstances and how prolonged depopulation might affect national will and morale.

Nothing guarantees that societies will successfully navigate the turbulence caused by depopulation. Social resilience and social cohesion can surely facilitate these transitions, but some societies are decidedly less resilient and cohesive than others. To achieve economic and social advances despite depopulation will require substantial reforms in government institutions, the corporate sector, social organizations, and personal norms and behavior. But far less heroic reform programs fail all the time in the current world, doomed by poor planning, inept leadership, and thorny politics.

The overwhelming majority of the world’s GDP today is generated by countries that will find themselves in depopulation a generation from now. Depopulating societies that fail to pivot will pay a price: first in economic stagnation and then quite possibly in financial and socioeconomic crisis. If enough depopulating societies fail to pivot, their struggles will drag down the global economy. The nightmare scenario would be a zone of important but depopulating economies, accounting for much of the world’s output, frozen into perpetual sclerosis or decline by pessimism, anxiety, and resistance to reform. Even if depopulating societies eventually adapt successfully to their new circumstances, as might well be expected, there is no guarantee they will do so on the timetable that new population trends now demand.

National security ramifications could also be crucial. An immense strategic unknown about a depopulating world is whether pervasive aging, anemic birthrates, and prolonged depopulation will affect the readiness of shrinking societies to defend themselves and their willingness to sustain casualties in doing so. Despite all the labor-saving innovations changing the face of battle, there is still no substitute in war for warm—and vulnerable—bodies.

Depopulation will transform how governments deal with their citizens and with one another.

The defense of one’s country cannot be undertaken without sacrifices—including, sometimes, the ultimate sacrifice. But autonomy, self-actualization, and the quest for personal freedom drive today’s “flight from the family” throughout the rich world. If a commitment to form a family is regarded as onerous, how much more so a demand for the supreme sacrifice for people one has never even met? On the other hand, it is also possible that many people, especially young men, with few familial bonds and obligations might be less risk averse and also hungry for the kind of community, belonging, and sense of purpose that military service might offer.

Casualty tolerance in depopulating countries may also depend greatly on unforeseen contingent conditions—and may have surprising results. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has provided a test. Both countries had very low birth rates on the eve of the invasion. And both the authoritarian aggressor and the democratic defender have proved willing to absorb grievous casualties in a war now grinding through its third year.

China presents perhaps the biggest question mark when it comes to depopulation and a willingness to fight. Thanks to both the one-child policy that was ruthlessly enforced for decades and the unexpected baby bust since the program was suspended nearly ten years ago, China’s military will perforce be manned in large part by young people who were raised without siblings. A mass-casualty event would have devastating consequences for families across the country, bringing entire lineages to an end.

It is reasonable to wager that China would fight ferociously against a foreign invasion. But such casualty tolerance might not extend to overseas adventures and expeditionary journeys that go awry. If China, for example, decides to undertake and then manages to sustain a costly campaign against Taiwan, the world will have learned something grim about what may lie ahead in the age of depopulation.

A NEW CHAPTER

The era of depopulation is nigh. Dramatic aging and the indefinite decline of the human population—eventually on a global scale—will mark the end of an extraordinary chapter of human history and the beginning of another, quite possibly no less extraordinary than the one before it. Depopulation will transform humanity profoundly, likely in numerous ways societies have not begun to consider and may not yet be in a position to understand.

Yet for all the momentous changes ahead, people can also expect important and perhaps reassuring continuities. Humanity has already found the formula for banishing material scarcity and engineering ever-greater prosperity. That formula can work regardless of whether populations rise or fall. Routinized material advance has been made possible by a system of peaceful human cooperation—deep, vast, and unfathomably complex—and that largely market-based system will continue to unfold from the current era into the next. Human volition—the driver behind today’s worldwide declines in childbearing—stands to be no less powerful a force tomorrow than it is today.

Humanity bestrides the planet, explores the cosmos, and continues to reshape itself because humans are the world’s most inventive, adaptable animal. But it will take more than a bit of inventiveness and adaptability to cope with the unintended future consequences of the family and fertility choices being made today.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News