By the time Burkina Faso’s health ministry declared an epidemic of dengue fever on October 18, 2023, there already were thousands of cases and hundreds of deaths. The World Health Organization (WHO) said it was the West African country’s deadliest bout with the disease in years.

Another dangerous outbreak quickly followed: a deluge of Russian disinformation.

Social media users, including many believed to be backed by the Russian government, began attacking work by Target Malaria, a not-for-profit research organization that fights mosquito-borne illnesses. The group, which is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, has worked to prevent malaria in Burkina Faso since 2012.

“But an army of fake social media users falsely accused the group of spreading disease, weaponizing mosquitoes, and creating biological weapons, while heaping praise on Russia,” according to Agence France-Presse.

In the face of the organized disinformation campaign, Target Malaria was forced to respond by calling the attacks “false” and “deeply regrettable.” Experts say the disinformation campaign is just one part of a concerted, systematic effort by Russia to sow mistrust in basic institutions such as health care, the government, the United Nations and even international humanitarian organizations.

Central to the Russian campaign was the African Initiative, an online outlet with deep ties to the late Wagner Group boss Yevgeny Prigozhin, who built a shadowy network of mercenary, disinformation and mining operations in Africa before he was killed in a mysterious plane crash in August 2023. In the wake of Prigozhin’s death, the Russian Defense Ministry has taken over the Wagner Group’s operations on the continent and rebranded it under the name Africa Corps.

Just as cases of dengue fever in Burkina Faso were surging in September 2023, the Russian military-run Zvezda TV broadcast a news story announcing the launch of the African Initiative.

Artyom Kureev, African Initiative director-general, has said his organization aims to become the “information bridge between Russia and Africa.” But its real goal is to disguise and spread disinformation in the hope that it will be seen as independent reporting and not as a Moscow-directed propaganda campaign.

The WHO reported a surge of dengue fever cases from six in July 2023 to “a staggering 708 cases” by September 9 and urged collaboration with partners such as Target Malaria. “Given the positivity ratio … it is imperative to uphold and reinforce public health measures,” the WHO said in a weekly bulletin.

Russian disinformation networks made that task much more difficult.

Dr. Mark Duerksen, a research associate at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), has spent years analyzing the growing impact of disinformation campaigns on the continent’s rapidly changing information systems. He called the recent Burkina Faso disinformation campaign Russia’s likely “next wave.”

“There are indications that the African Initiative is probing public health as something amenable to this kind of information warfare,” he told ADF. “They seem to have found another soft spot that they’re going to exploit. It’s really cynical because it’s going to make public health efforts more difficult on the continent. It’s going to make fewer people access care.”

Russian Disinformation in the Sahel

Hybrid warfare combines conventional forms of armed conflict with nonconventional strategic tools, including information operations to influence and subvert or reframe events. Duerksen says it is a part of the “suite of services” Russia offers to isolated autocratic regimes such as the military juntas that have taken over Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger in recent years.

First, Russia identifies and inflames local grievances. In the Sahel, the biggest vulnerability is ineffective security forces facing a tidal wave of expanding violent extremist organizations — regional groups with links to al-Qaida and the Islamic State group terrorist organizations.

Next, Russian operatives cultivate local influencers who spread propaganda and disinformation while building a network on social media and promoting demonstrations to give the appearance of popular support. Then Russian mercenaries arrive and lead counterterrorism training and operations while establishing their payment through contracts for mineral extraction. In the wake of its military operations across Mali and the Central African Republic, the Wagner Group was credibly accused of numerous civilian massacres, atrocities, human rights violations and other war crimes.

Once the mercenaries are in place, the disinformation and influence campaigns can be declared a success.

As the head of research at Logically, a technology company that tracked a surge of pro-Russian and anti-French narratives related to Niger surrounding the country’s military coup in 2023, Kyle Walter has long suspected that Russian funding and social media networks are responsible for fake grassroots rallies. The New York Times reported that Ahmed Bello, the president of a Nigerien civil society group whose acronym is written as Parade, distributed as many as 70 Russian flags at multiple protests in Niamey and that the Russian government provided funding through intermediaries conducting similar activities in Mali.

“It is with them that we work to develop the expansion of Russian ideology in Africa,” Bello told the Times.

Researchers at Microsoft have identified Parade as the handiwork of Russia’s Foreign Ministry, and a senior European military official told the Times that the group is a front for Kremlin-backed operations on the continent.

“It’s a whole toolkit,” Duerksen said, explaining the Wagner Group’s blueprint. “It can help [juntas] stay in power and keep the opposition and the journalists at bay. When the disinformation that they’re offering has helped actually bring these regimes to power in the case of the [Sahel] military juntas, they are then intertwined with those regimes.”

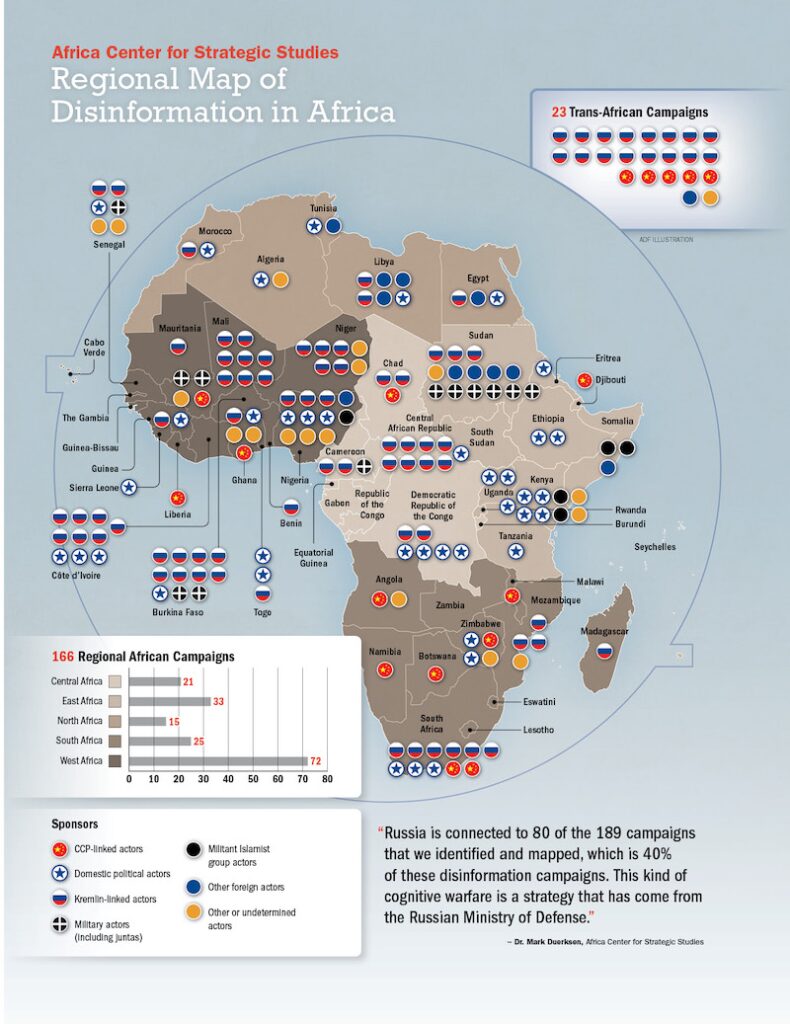

In a March 2024 report that drew from the work of more than 30 African researchers and organizations, the ACSS identified Russia as the primary sponsor of disinformation in Africa.

“Russia is connected to 80 of the 189 campaigns that we identified and mapped, which is 40% of these disinformation campaigns,” Duerksen said. “This kind of cognitive warfare is a strategy that has come from the Russian Ministry of Defense. This isn’t just a side project. This is a clear emphasis for the Russian military, and they go about this pretty systematically.”

Whereas the Russian government previously denied any ties to its mercenary groups’ operations, the shift from Prigozhin’s Wagner network to the military-controlled Africa Corps is profound in that Russia is now accountable for its actions.

“Who’s going to be stuck holding that bag with some kind of accountability?” Duerksen said. “Wagner had always given them this deniability that they weren’t associated with whatever they were up to. Now the Russians own it.”

The Wagner Blueprint

The Wagner Group was Russia’s primary vehicle for its ambitions in Africa dating back to 2017, when Prigozhin and his mercenaries arrived and began building a sprawling network.

“They were trying a lot of different disinformation tactics, pushing a lot of different narratives, even conflicting narratives like backing two political candidates at the same time,” Duerksen said. “It seems like they were doing a kind of market research, a lot of experimentation.”

Among the most effective strategies is using local languages across social media networks and hiring local people to spread disinformation.

“They’ve realized the messenger matters, that having somebody who either speaks the local language, is really in tune with the local issues or speaks the local dialect is much better than a Wagner Telegram channel based in St. Petersburg,” Duerksen said. “They see these as the vanguard of their influence and how they can get groups into the streets.”

In the Sahel, with its complicated Francophone history, Russia found a vulnerable, willing consumer of its disinformation.

“There were problems with security,” Duerksen said, “so they just really hammered these messages and really tried to contort the political discourse toward this kind of disillusionment, this cynicism, this kind of toxic energy, not channeling it toward anything constructive or productive, but toward the cheering for military coups. It’s kind of a nihilistic politics now.”

Duerksen said that part of Russia’s disinformation design is to focus on three audiences.

The first group consists of local people who consume disinformation content, embrace it and become amplifiers and standard holders. “They’re the ones who are in the street holding Russian flags,” Duerksen said. “That’s a small group, those who actually have become the domestic purveyors.”

The second group is larger, with local people for whom disinformation content is designed to confuse and result in disengagement with politics and social issues. “They’re oftentimes being intimidated. If they try to express an opinion or ask a question in some of these information spaces, the troll army descends on them.”

The third group consists of regional and international media and observers who sometimes share only a surface-level understanding of distant issues and affairs. “It’s hard to cover events, so it gets framed as a popular uprising. I think that’s become very intentionally manufactured around the Sahel trends. It’s advancing a strategic objective that Russia has in the region.”

Analyst Dan Whitman of the Foreign Policy Research Institute has similarly concluded that Russia is exploiting and profiting from violence in the Sahel.

“Instability is the Garden of Eden for disinformation,” he told Voice of America. “I would say [in] two or three years, [Russia] has made the most rapid propaganda successes in the history of propaganda.”

Pushing Back Against the Narrative

Russian disinformation has been used to insulate authoritarian regimes from accountability. In this way, military juntas in the Sahel are no different from Vladimir Putin’s oppressive reign in Russia. Never-ending disinformation campaigns mean that there always will be another distraction, another way to deflect criticism, another internal or external enemy to blame. But pushback is inevitable, especially in the Sahel, where insecurity touches nearly every life and is only getting worse.

In April, more than 80 political parties and civil groups in Mali issued joint statements calling for presidential elections and an end to military rule. Mali’s junta responded with more oppression, suspending all political activities and barring the media from covering politics — moves it claimed were necessary “for reasons of public order.”

But Malian dissenters are showing that they aren’t going away.

On April 24, 2024, a group of political parties and civil society organizations appealed to Mali’s Supreme Court “with the aim of annulling the decree which they consider tyrannical and oppressive.”

The mere existence of resistance is a clear sign that a media ecosystem of disinformation is not invulnerable. By pushing back, people undermine the narrative that their military rulers have popular support. Throughout the Sahel, it is not difficult for Malians, Burkinabe and Nigeriens to see that their so-called transition government leaders have no plans to hold elections any time soon.

“Things aren’t going well in the Sahel under these military regimes,” Duerksen said. “Security is getting worse. Economies are disintegrating. That’s been one of the great tricks of these disinformation campaigns. They’ve helped create and keep alive this image that the military juntas are popular.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News