The Israeli military says it carried out nearly 500 strikes against Syrian military targets in the days since the fall of President Bashar al-Assad, while its troops moved into a demilitarised zone in the Golan Heights that was established following the 1973 Middle East war. Analysts say Tel Aviv may be preparing for potential “chaos” – and for a new regime in Syria.

Israel wants to have a relationship with the new regime in Syria, Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu said in a video posted on X on Tuesday. But the statement also came with a threat.

“If the new regime in Syria allows Iran to re-establish itself, or allows the transfer of Iranian weapons to Hezbollah – we will respond forcefully and we will exact a heavy price.”

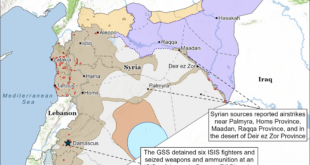

Just hours after the Syrian rebels of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) entered Damascus on Sunday, signalling the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, the Israeli military began a wave of air strikes on targets in Syria.

The Israeli military said on Tuesday that it had carried out almost 480 strikes in Syria in 48 hours.

Israeli Defence Minister Israel Katz said on Tuesday that Israeli forces had completed “the destruction of the Syrian navy”.

According to the UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, which relies on a vast network of sources across Syria, Israel bombed airports, radar installations, armoured vehicles, arms and ammunition depots in several regions, including Damascus. A “scientific research centre” near Damascus, suspected of being linked to Syria’s chemical weapons programme, was also bombed.

A ‘stable’ enemy

Israel’s stated aim was to destroy all remaining weapons in warehouses and military units controlled by the former regime.

“Israel is facing a situation where there is a political and security vacuum in Syria, and is taking advantage of it to carve out advantages for itself,” says Didier Leroy, a Syria specialist at Belgium’s Royal Military Academy and the Université libre de Bruxelles (Free University of Brussels).

“Because Israel is aware that however things turn out, it will be easier to deal with – and put pressure on – a new government that is militarily weak.”

Up until now, having Bashar al-Assad’s regime in power has largely served Israel’s interests in Syria. Although Assad remained an ally of Iran, and allowed Hezbollah to transport weapons destined for Lebanon via Syria, his regime was too weak to risk direct confrontation with Tel Aviv. Assad, therefore, allowed Israel to carry out air strikes against Hezbollah or Iranian interests, individuals and military installations without ever retaliating.

Syria under Assad “was a convenient and, above all, stable enemy”, says Sébastien Boussois, Middle East specialist at the Geneva-based Observatoire géostratégique (Geneva Strategic Observatory) and the author of “Daech, la suite” (After Daesh) on the future of the Islamic State group.

“Bashar al-Assad’s regime rarely took direct action against Israel, preferring to focus on internal threats.”

If it was once a feeble adversary, Syria has now become a question mark. This uncertainty is further reinforced by the ambiguity surrounding the personality of Mohammed al-Golani, leader of the HTS, who is poised to become Syria’s new strongman. While he may present himself today as a “pragmatist” – which could encourage him to seek to avoid a showdown with Israel – his past affiliation with al Qaeda raises many questions about his real intentions.

Syria’s new masters are driven by “an extreme ideology of radical Islam”, Israel’s Foreign Minister Gideon Saar said in a press briefing on Monday. “That’s why we attacked strategic weapons systems, like remaining chemical weapons or long-range missiles and rockets, in order that they will not fall into the hands of extremists.”

Progress on the ground

Israeli military forces have also been conducting a ground offensive: Israeli troops have since Saturday been positioned in the buffer zone between the Israeli-occupied part of the Golan Heights and Syria. This is the first time in 50 years that Israeli tanks have been present in this demilitarised buffer zone, established in 1974 by an armistice agreed by the two countries.

“This is a historic day in the history of the Middle East,” Netanyahu said from the Golan Heights on Sunday, hailing the fall of Assad’s regime.

The 1974 agreement with Damascus “collapsed” with the fall of the Syrian regime, he said, paving the way for an Israeli presence. He also announced the imposition of a curfew on localities in the buffer zone.

Located in south-western Syria, on Israel’s eastern border, with Lebanon to the north and Jordan to the south, the Golan Heights is of major strategic importance to Israel, which has occupied parts of it since the Six-Day War of 1967. Some 30 Israeli settlements, or around 20,000 people, live there alongside a Syrian population mainly made up of Arabs from the minority Druze community.

The occupation of the Golan Heights by Israel is deemed illegal under international law, but the territory has become “a major resource for Israel’s access to water”, says Boussois. Control of the Golan Heights and its many rivers and aquifers provides Israel, which is mostly desert, with a third of its water supply.

The region has also become “a mecca for winter sports and an area well-known for winemaking”, he adds.

‘A sort of new buffer zone’

But the stakes are also military. The Golan Heights, 2,800 metres in elevation at its highest point, offers an ideal vantage point from which to monitor southern Syria, and in particular the capital, Damascus, 60 kilometres away.

“Today, the Golan Heights represents the No. 1 threat to Israel,” says Boussois. “Bashar al-Assad’s weakened regime had never taken serious diplomatic or military action to try to reclaim the Golan. But HTS might later want to claim it be returned to Syrian control.”

The disputed territory could even become the scene of direct fighting.

“During the [2011] Syrian civil war, jihadist elements attempted to cross the Israeli border via the Golan Heights. Tel Aviv is therefore on high alert, as the Golan Heights could – if the situation becomes chaotic – turn into the scene of direct confrontation with Israel,” Boussois says.

By advancing into the demilitarised buffer zone in the Golan Heights, Israel seems to want to “create a new buffer zone further north”, says Leroy. “At the same time, advancing northward could certainly enable it to secure routes used by Hezbollah to reach Lebanon, and ensure that the areas adjacent to the Golan are secure.”

While Israel has repeatedly insisted that this advance is a “limited and temporary” measure, it could also, in the medium term, “serve as a bargaining chip with the new government” in Syria, Leroy observes. In some future negotiation, “Israel could only agree to return the conquered territories if this government did not show itself to be too hostile.”

This whole offensive is “quite conventional for Israel”, says Leroy. Faced with the unknown, “it wants to create a balance of power through military means”.

“And future political discussions will have, as their starting point, this new balance of power.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News