The security calculations of the Shia Muslim-dominated government in Baghdad were upended by the collapse of the Assad regime in neighboring Syria, which brought Sunni Muslim Islamists to power on Iraq’s western border.

The Türkiye-backed political change in Syria leaves Iran as Iraq’s main remaining regional ally.

Iraqi Shia leaders are concerned that a drawdown of U.S. forces in Iraq, agreed before Assad’s collapse and planned for September, will render the country vulnerable to Sunni militants.

Trump’s decision to lift sanctions on the new Syrian government did not alter the U.S. sanctions architecture on Iraq, including Treasury Department restrictions intended to prevent the flow of U.S. dollars into Iran.

In the aftermath of the 2003 U.S. ouster of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, which empowered the country’s Shia majority, friendly governments in Tehran and Damascus provided Iraq with a degree of strategic depth. Iraq’s leaders were able to balance the country’s relations with Iran and the U.S. — adversaries of each other, but which shared an interest in Iraqi stability. Tehran and Washington worked in tandem, although separately, to help Iraq defeat the challenge from Islamic State (ISIS) during 2014-2017, a threat that originated from eastern Syria, which had slipped out of Damascus’ control during the civil war that erupted in 2011. Baghdad’s relationship with the Assad regime was not warm, but Assad was a close ally of Iran, and his regime supported – and was supported by – Iran-aligned Iraqi militias that exercised significant influence in Iraq’s politics and security architecture. As the ISIS threat receded and Iraqi forces expanded their capabilities, the U.S. and Iraq agreed in September 2024 to transition their security relationship from a multilateral anti-ISIS mission to a bilateral U.S.-Iraq strategic framework agreement, including a substantial drawdown of the 2,500 U.S. forces in Iraq by September 2025.

The December 2024 collapse of the Assad regime weakened Iran strategically, but also significantly altered Iraq’s security posture, rendering Baghdad increasingly dependent on both Tehran and Washington. The accession to power in Damascus of interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa – at one time linked to al-Qaeda’s operations in Iraq – has alarmed Iraq’s Shia-dominated government and security establishment, even though al-Sharaa distanced his organization from global jihadist groups nearly a decade ago. Recognizing that the new government in Damascus remains weak, relying on fighters from al-Sharaa’s Hayat al-Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) organization and Assad security holdovers, Iraqi leaders are deeply concerned about the spillover of Sunni Islamists from Syria that could revive insurgent networks within Iraq’s borders.

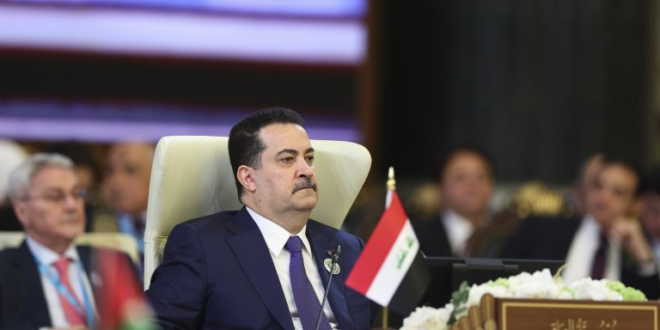

The continued porousness of the Iraq-Syria border raises the potential for remaining ISIS cells in Syria to reinforce their compatriots in Iraq, particularly in remote areas of Anbar, Nineveh, Diyala, and Kirkuk provinces. However, there have not been reports, to date, of any significant infiltration of ISIS or other Sunni militants into Iraq. The power shift in Syria also might improve the prospects of hardline, sectarian Shia leaders in the national elections in November, including former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki – who apparently hopes to return to power and replace his more moderate rival, Prime Minister Mohammad Shia al-Sudani, who seeks another term. Experts have attributed the rise of ISIS in Iraq in part to Maliki’s anti-Sunni policies during his 2006-2014 rule.

Iraqi leaders are adjusting to the new power structure in Syria with a mix of diplomacy and security repositioning. In March, the new government’s foreign minister, Asaad al-Shaibani, conducted the first high-level, post-Assad Syrian visit to Baghdad, calling for the reopening of the border and declaring enhanced bilateral trade a priority. On April 17, Sudani met with Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa in Qatar – their first encounter since Assad’s collapse. The talks, convened by Amir Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, were al-Sharaa’s first meeting with an Iranian ally, having previously visited several Gulf Arab capitals. The meeting reportedly focused on regional security issues, including reopening and controlling their joint border and counterterrorism. Sudani also invited al-Sharaa to attend the Arab League summit meeting in Baghdad on May 17. The two leaders stressed the importance of “respecting the sovereignty” of each country and “refusing any form of foreign interference,” according to a statement released by the Syrian presidential office.

Officials in Baghdad, as well as Tehran, have also counseled Damascus not to exact retribution from Assad’s Shia-linked supporters, such as the Alawite community. In his meeting with al-Sharaa, Sudani called for “an inclusive political process” in Syria, which guarantees “the protection of all social, religious and national components.” In addition, Iraqi officials, particularly those in charge of the semi-autonomous Kurdish-inhabited north, are concerned about the future of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which is dominated by Kurdish militia fighters. Iraqi leaders, joined by their U.S. counterparts, insist that Damascus allow Syria’s Kurds substantial autonomy. On Friday, the prime minister of Iraq’s Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) met with Secretary of State Marco Rubio in Washington. Although the meeting centered on U.S. energy relations with the KRG, a U.S. readout of the meeting noted that the two discussed the mutual U.S. and Iraqi interest in “protecting the rights of religious and ethnic minorities in Iraq and Syria.” Iraq’s Kurdish leaders are also concerned that the accession to power of HTS in Syria has empowered Ankara, which backed the group’s offensive to topple Assad and wield substantial influence over the new Syrian government. Iraq’s Kurds seek to end Turkish incursions into northern Iraq to engage in “hot pursuit” against Kurdish militants of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), although the Iraq-Türkiye border has quieted somewhat since the PKK announced an end to its armed struggle against Ankara.

Despite al-Sharaa’s pledges to respect the rights of all Syrian communities, the leaders of Iraq’s Iran-aligned Shia militia objected to al-Sharaa’s attending the Arab League summit in Iraq. Pro-Iranian Shia factions in Iraq continue to associate al-Sharaa, and al-Qaeda more broadly, with the 2006 bombing of the Al-Askari Shia shrine in Samarra, which set off years of intense Sunni-Shia civil warfare in Iraq. At the time, President George W. Bush stated, “It is pretty clear – at least the evidence indicates – that the bombing of the shrine was an Al-Qaeda plot, all intending to create sectarian violence.” Recognizing that visiting Iraq might spark intra-communal tensions in Iraq, al-Sharaa declined Sudani’s invitation to the summit.

In addition to engaging Syria’s leadership, Baghdad has undertaken practical steps to limit any spillover of Sunni militancy or other political repercussions from the power shift in Syria. In late December, Iraq dispatched National Intelligence Director Hamid al-Shatri to Damascus for talks with Syria’s transitional government on counterterrorism and intelligence-sharing. Iraq has also intensified its border control operations, targeting smuggling networks and increasing surveillance of cross-border movements. And, some Shia units of the broader Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), which includes strongly Iran-aligned militias, have been deployed to reinforce Iraqi Armed Forces positions along the border to prevent Sunni militant infiltration.

The perceived threat emanating from Syria raises questions about the path forward for U.S.-Iraq security cooperation, the parameters of which were set three months prior to Assad’s collapse. The Associated Press quoted U.S. and Iraqi officials in January as stating that the Iran-aligned Shia militia factions, which have agitated for a U.S. withdrawal to the point of launching more than 250 rocket and missile attacks on bases housing U.S. military personnel since early 2021, are reconsidering their opposition to a continued U.S. presence “due to the changing regional dynamics.” The militia leaders’ adoption of a less hostile position toward the U.S. has, in turn, prompted the government to soften its insistence that Iran-backed groups disarm and transition into purely political parties. Iraqi and U.S. leaders have not, to date, altered plans to transition the U.S.-Iraq relationship to an enduring strategic framework requiring some of the 2,500 U.S. forces to withdraw, while many redeploy to KRG-controlled territory in northern Iraq. The planned realignment is scheduled for completion in September. Still, some sources indicate that the Iraqi government would prefer the U.S. to delay the repositioning until Baghdad is confident it can address any new threats emanating from Syria.

Another open question is whether President Donald Trump’s lifting of all U.S. sanctions on Syria will generate resentment in Iraq. The U.S. Department of the Treasury has sanctioned several Iraqi banks for enabling Iran-backed actors to use their services to acquire U.S. dollars. Trump also has refused to extend a sanctions waiver that had enabled Iraq to pay Iran for the electricity and natural gas it supplies to Iraq. The waiver denial could set the stage for Iran to cease its energy deliveries to Iraq, rendering the country particularly vulnerable in the hot summer months and beyond. By contrast, on Friday, Treasury implemented Trump’s Syria sanctions decision by issuing Syria General License (GL) 25 “to provide immediate sanctions relief for Syria in line with the President’s announcement for the cessation of all sanctions on Syria…effectively lifting sanctions on Syria.” The statement noted the license will “enable new investment and private sector activity consistent with the President’s America First strategy,” adding: “The U.S. Department of State is concurrently issuing a waiver under the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act (Caesar Act) that will enable our foreign partners, allies, and the region to further unlock Syria’s potential.” Experts note Iraq, despite its longtime alliance with Washington, is paying a price for its relations with Iran, whereas Syria, whose leadership is untested, is reaping the benefits of expelling Iranian operatives and allies from Syrian soil.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News