More complex than a ‘yes’ or ‘no’

Even so, I was still able to interview 12 ethnic Hungarian community leaders, some of whom spoke on condition of anonymity, while others agreed to give only their first names and line of work.

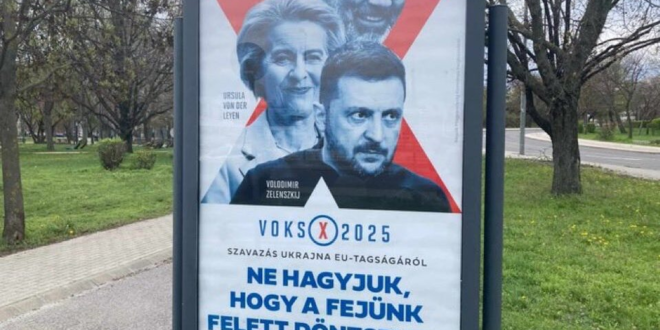

These individuals offered a range of opinions. Some echoed the talking points about corruption and economic capacity that have made their way into the Hungarian government’s current advertising campaign around Voks2025. But few spoke in terms that could be easily reduced to the poll’s yes-or-no question.

In Uzhhorod’s central tourism district, I met business owner Gyorgy Rusnyak at his restaurant, Under the Castle. Decorated with antique signs from the periods when Transcarpathia belonged to Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Ukraine, Rusnyak said he wanted Under the Castle to be a multilingual cultural centre as well as a restaurant when he opened it in the late 1980s.

Proudly Hungarian and touting his cross-border political friendships – “Hungary’s ambassador eats here all the time” – Rusnyak nevertheless said the referendum shows how politicians needlessly stoke ethnic tensions and dismissed Orban’s campaign against Ukraine’s EU bid as a minor stumbling block.

As a committed European who wants to get rid of Russian influence – “We’ve had enough of the Russians here” – he explained that like his café, Ukraine’s future was going to be in Europe and multicultural. “It would be better if Ukraine were a part of the EU,” he declared without hesitation, “In fact, we’re already Europeans – it’s really just a matter of formalities.”

A Transcarpathian Hungarian woman who works as a translator at a multinational company said that EU membership would benefit the business community more broadly, not just restaurants and the hospitality industry. “Those companies that do business abroad will be able to export more easily,” she explained.

Currently, it takes so long to export from Ukraine that there are often lines of trucks at external border crossings – a problem, she said, that would disappear under the EU single market regime: “Customs regulations wouldn’t be so strict.”

Some Transcarpathian Hungarians echoed Orban’s concerns about the potentially negative economic consequences of granting Ukraine EU membership. They also described Ukraine as a financial burden and, echoing Orban, predicted that other member states might blanch at the idea of sending so much money to such a corrupt and destroyed country.

Even while indicating their opposition to Ukraine’s EU bid, these conversations revealed Transcarpathian Hungarians have their own rationales that depart from Hungary’s jingoistic messaging. Government-funded PR frequently verges on a “love it or leave it” message that disparages so-called outside or foreign criticism of Hungary. But Jolan, a translator from a village near Berehove, was open about her negative view of Hungary’s environmental conditions, in particular.

I met Jolan as she boarded a bus from Hungary to Uzhhorod. She was returning for the Easter break from her job at a foreign-owned factory outside Budapest. Jolan said that workers were in the dark about the disposal of dangerous chemicals at the factory, even though Hungary is subject to EU environmental rules. Based on this experience, she was sceptical that EU membership would benefit Ukraine’s environment. “It’ll be the same as it is in Hungary,” she observed. “The water, the air – it’s all polluted here.”

“EU membership will mean more income,” she continued, “but there will be a lot of ruin to nature and the environment.”

Jolan did not want Ukraine to join the EU, but not for the reasons cited on government-funded advertisements; she did not care whether “Brussels” or Zelensky “went over our heads”, in the words of one advertisement. In fact, Transcarpathian Hungarians are willing to put down Hungary’s poor environmental record if this provides a reason for not joining the EU.

I don’t know – is it better for Roma in Hungary being in the EU? Unfortunately, all over the world there’s discrimination against Roma.

– Roma activist Eleonora “Lola” KulcsarUzhhorod’s Hungarian-speaking Roma NGO leaders definitely want Ukraine in the EU, according to Roma activist Eleonora “Lola” Kulcsar. I met Kulcsar at the headquarters of the Blaho Foundation, where she runs educational programs for Roma children. Transcarpathia has a large Roma population. Many speak Hungarian as a first language at home, including Kulcsar. “Hungarian is my mother tongue,” she insisted proudly.

“If it means peace for Ukraine, absolutely,” Kulcsar replied when asked for her opinion on Ukraine’s EU bid. “Peace is the most important thing.”

Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine displaced many Roma who fled to Transcarpathia, where the Blaho Foundation began setting up shelters. Ongoing Russian attacks are still forcing Roma from their homes. Just the day before, Kulcsar said, a new family arrived at Blaho’s shelter. The invasion would stop this and these families could return home, she reasoned, if Ukraine were progressing toward membership.

Right now, though, she complained that funders were using Ukraine’s position outside the EU to shift money away from organisations in Uzhhorod. Some international funders have declined requests to focus on groups operating in Ukraine’s frontline cities. Others, even though they traditionally support only EU-based projects, donated out of concern following Russia’s full-scale invasion. Blaho has now lost these funding sources, too. “We’re asking some people but they’re saying, ‘You’re not in the EU. We can’t support you’.”

But Kulcsar was sceptical whether, in the long term, EU membership would really improve the conditions for Transcarpathia’s Hungarian-speaking Roma. “I don’t know – is it better for Roma in Hungary being in the EU?” she asked rhetorically. “Unfortunately, all over the world there’s discrimination against Roma.”

Conditions for Roma have not historically improved when geopolitical affiliations change, Kulcsar explained. EU accession did not bring about enough change in Hungarian society to eliminate racism. Anti-Roma racism would persist in Uzhhorod, no matter how thoroughgoing an effect the EU accession process would have on Ukrainian society.

Transcarpathia’s leading Hungarian politicians, including members of the Ukrainian Hungarian Democratic Union political party, have already gone on the record in favour of EU membership. Eighteen months ago, after the EU launched accession negotiations with Ukraine, a group of UHDU leaders issued an open letter urging Viktor Orban to support this process.

Professor Laszlo Zubanics, who teaches European Affairs at the National University of Uzhhorod and helped draft the letter, said he still supported Ukraine’s EU membership despite Orban’s ongoing PR campaign against the bid.

“In the current situation,” Zubanics told me from his university, “for Transcarpathian Hungarians as much as for the whole of Ukraine, it would be the kind of step forward that would solve many painful problems.”

Zubanics detailed recent successful negotiations with Kyiv lawmakers as well as efforts to build solidarity among Ukraine’s ethnic minority groups. He noted that as of last year, such minority students are now legally allowed to use their native languages between classes and during breaks. Various national minority groups worked together to negotiate the change. “We were able to include every national minority one after the other in this effort,” he said.

Zubanics’s success with this approach has led him to be doubtful that Hungary’s national consultations and other referenda can foster dialogue and debate. Voks2025 was, in his words, “inexpedient” and an example of a policy to intimidate migrants and other marginalised groups. Reason, not emotions, should guide voters, he said.

“It would have been worthwhile to follow through with these topics at the state level,” Zubanics observed. “Hungary and Ukraine, first and foremost, need to deal with these difficult questions at an international or ministerial level.”

With so much attention focused on what Hungarian voters want, several people I interviewed wondered aloud why no one from the Budapest government had asked their opinion. After all, Transcarpathian Hungarians would be most affected by Ukraine’s EU accession.

In the words of one civil society activist: “They haven’t even bothered to ask us! I’m Hungarian. But I’ve never heard once someone say, ‘What do you think about this?’”

Another NGO worker reiterated this point. “We don’t understand why they have to do it,” he said. “And we’re the ones living here.”

Zubanics agreed that the average Transcarpathian Hungarian feels Voks2025 has left them feeling like their opinions don’t matter. He couldn’t say, for example, if anyone from the minority community’s political leadership had been consulted.

“They must have asked some people,” he replied, “But I didn’t get this kind of request.”

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News