Abstract: The 12-day Iran war may be over, but the threat of Iranian reprisal attacks now looms large, and will for the foreseeable future. European authorities exposed plots in Sweden and Germany even as the war was being waged, and Israeli authorities issued a warning over potential attacks in the United Arab Emirates a couple of weeks later, specifically citing heightened concerns in the wake of the war with Iran. Iranian operatives or their agents could also attempt to carry out attacks inside the United States, leveraging what U.S. counterterrorism officials have describe as a “homeland option” developed over years. Given the U.S. role in bombing the Fordow nuclear complex, it should not be a surprise that U.S. authorities quickly issued a terrorism advisory warning of potential Iranian plots in the homeland. Drawing on past cases of Iranian plots in the United States and elsewhere, this article explores the primary pathways available to Iran conduct or enable a terrorism act in the United States. These include deploying Iranian agents, criminal surrogates, terrorist proxies, or actively seeking to inspire lone offenders to carry out attacks within the homeland.

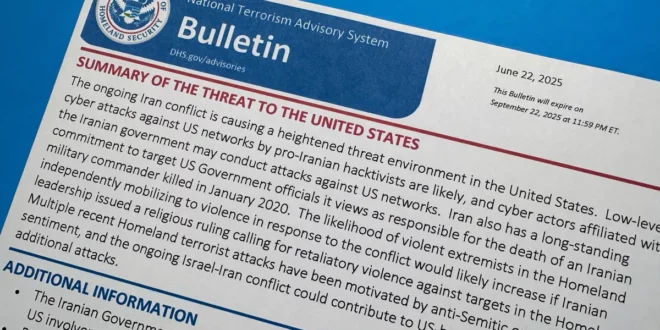

The 12-day Iran war may be over, but the threat of Iranian reprisal attacks now looms large, and will for the foreseeable future. Authorities in Europe have already exposed two plots linked to Iran, one targeting Israeli and American interests in Sweden1 and another targeting Jewish institutions and specific Jewish individuals in Germany.2 But Iran and its proxies have spent years investing in a “homeland option”3 here in the United States as well. In just the past five years, U.S. authorities have disrupted at least 17 Iranian plots in the homeland, including those involving Iranian operatives as well as terrorist and criminal proxies.4 Other cases that fell short of plotting for a specific attack include a Hezbollah operative in Texas who purchased 300 pounds of ammonium nitrate,5 an explosive precursor, and another who carried out surveillance missions in New York and Canada.6 U.S. law enforcement and intelligence authorities remain on high alert for potential revenge attacks by Iranian agents or proxies arising out of the 12-day Israel-Iran war and the June 21 U.S bombing of Iranian nuclear facilities. The FBI increased its monitoring of Iran-backed operatives in the United States in advance of the U.S. strikes7 and then, in June 2025, reassigned counterterrorism agents recently tasked to work on immigration cases back to the counterterrorism mission.8 Federal officials advised their state and local government counterparts to be vigilant for potential domestic plots in the United States,9 and the Department of Homeland Security issued a National Terrorism Advisory System bulletin warning that the “Iran conflict is causing a heightened threat environment in the United States.”10

With a ceasefire in place, Iran is likely wary of being tied to any successful plot for fear of inviting further reprisal attacks for any acts of terrorism abroad. Iran may even be less capable of executing sophisticated plots of its own right now, in light of the severe damage to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC)—such as the killing of IRGC intelligence organization chief, Mohammad Kazemi, as well as his deputy.11 Near-term plots are therefore more likely to come from criminal proxy groups or lone offenders operating at arm’s length from Tehran (like the plots in Sweden and Germany), or from homegrown violent extremists inspired to carry out attacks to avenge Iran’s humiliating losses. But in the long term, there can be no doubt that Iran will turn to foreign plots of various kinds to avenge the loss of so many senior officials12 and the damage to Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs, much as Iran has sought to avenge the January 2020 killing of Quds Force leader Qassem Soleimani in a U.S. airstrike. Iran certainly has the capacity to do so.

Iranian Threats in Context

In the days leading up to the U.S. strikes against three Iranian nuclear facilities, Iran reportedly sent a message to President Donald Trump threatening to “activate sleeper-cell terror inside the United States” if the U.S. military attacked Iran.13 Such threats should not be taken lightly, given the sharp uptick14 in Iranian external operations15 around the world—including in the United States—over the past decade, as well as the history of Hezbollah operatives carrying out surveillance of potential targets in the U.S. homeland.16

Iran sees terrorism as an extension of foreign policy—an asymmetric means of reaching its adversaries beyond its borders despite their military superiority. According to CIA reporting in the mid-1980s, “Tehran has used terrorism increasingly to support Iranian national interests,” not only as a means to export its revolution.17 That said, in a 1987 report, the CIA underscored that “the [Iranian] constitution gives the Revolutionary Guard responsibility for exporting the revolution, in addition to its [domestic] security functions.”18 Indeed, while Iran’s support for terrorism was meant to further its national interest, it also stemmed from the clerical regime’s perception “that it has a religious duty to export its Islamic revolution and to wage, by whatever means, a constant struggle against the perceived oppressor states.”19 There can be no question that Iran today sees Israel and the United States in that light, and its revolution challenged as never before.

The revolutionary regime in Tehran has carried out plots abroad targeting dissidents, journalists, foreign officials, and others since just months after the 1979 revolution.20 One of the first targeted a former Iranian official turned dissident in Bethesda, Maryland, in July 1980.21 But for years, the U.S. intelligence community assessed that Iran and its proxies were unlikely to carry out attacks within the United States. Then came the 2011 IRGC plot to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the United States in a popular Washington, D.C., restaurant,22 which forced the U.S. intelligence community to reassess its assumptions. The result was a new assessment, expressed by then-Director of National Intelligence James Clapper in congressional testimony, that the plot “shows that some Iranian officials — probably including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei — have changed their calculus and are now more willing to conduct an attack in the United States in response to real or perceived U.S. actions that threaten the regime.”23 Since then, Iranian agents or their proxies have been tied to 27 plots in the United States, according to a dataset maintained by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.24 Around the world, over the past five years, the dataset tracks 157 cases of Iranian foreign operations, including 75 involving Iranian agents, 22 involving criminal proxies, and 55 terrorist proxies.25 “U.S. law enforcement has disrupted multiple potentially lethal Iranian-backed plots in the United States since 2020,” DHS reported in June 2025. “During this timeframe, the Iranian government has also unsuccessfully targeted critics of its regime who are based in the Homeland for lethal attack.”26

In its 2025 threat assessment, the DNI assessed that Iran “will continue to directly threaten U.S. persons globally and remains committed to its decade-long effort to develop surrogate networks inside the United States,”27 harking back to the 2011 plot. The DHS Homeland Threat Assessment concurred, reporting “we expect Iran to remain the primary sponsor of terrorism and continue its efforts to advance plots against individuals—including current and former US officials—in the United States.”28

Such plots have been on the rise in recent years,29 and could involve Iranian operatives, criminal surrogates, or terrorist proxies. Authorities also worry that inspired lone offenders could decide to carry out less sophisticated but still deadly attacks of their own in support of Iran.30

Iranian Agents

In the past, Iran has both dispatched agents to the United States and tasked persons residing in the country to act as their agents. In November 2003, New York City police spotted two Iranian guards employed at the Iranian Mission to the United Nations filming subway train tracks. Then, in May 2004, two different Iranian Mission security guards were observed videotaping infrastructure, public transportation, and New York City landmarks.31

Iranian agents have also conducted surveillance of Iranian dissidents and institutions inside the United States. Consider the case of Ahmadreza Mohammadi-Doostar, a dual U.S.-Iranian citizen living in Iran, and Majid Ghorbani, an Iranian citizen who resided in California. In 2017-2018, Ghorbani carried out surveillance of Iranian dissidents and dissident rallies in the United States and provided that information to Doostar. Doostar conducted surveillance of Jewish student organizations in Chicago.32 In 2020, the two were sentenced to prison “in connection with work on behalf of Iran.”33

Threats of Iranian plots in the United States spiked after the January 2020 targeted killing of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani. Within days of the U.S. airstrike that killed Soleimani, U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies released a joint intelligence bulletin warning of the need “to remain vigilant in the event of a potential [Government of Iran] GOI-directed or violent extremist GOI supporter threat to US-based individuals, facilities, and [computer] networks.”34

Over the course of 2020 and 2021, a group of Iranian operatives based in Iran used an Iranian-American in California and unwitting American private investigators to collect information about the movements of Iranian-American human rights campaigner Masih Alinejad in support of a plot to kidnap her and transport her by sea from New York to Venezuela and from there to Iran.35 This Iranian foreign operations network was run by Iranian intelligence operative Alireza Shavaroghi Farahani whose operatives targeted victims in the United States,36 Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.37 The plot was foiled when authorities issued an indictment of members of the Iranian intelligence network in July 2021.38

Meanwhile, in February 2021, a Belgian court convicted Assadollah Assadi, an Iranian diplomat based in Vienna, of organizing a July 2018 plot to bomb the annual convention of the National Council of Resistance of Iran—the political wing of the Mujahedeen-Khlaq, MEK—near Paris.39 Three accomplices, all Iranian-Belgian dual citizens, were also sentenced for their roles in the plot.40 According to German and Belgian prosecutors, Assadi was no run-of-the-mill diplomat but rather an Iranian intelligence officer operating under diplomatic cover.41 In a statement, prosecutors tied Assadi to Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), whose tasks “primarily include the intensive observation and combating of opposition groups inside and outside Iran.”42

“Iran maintains its intent to kill US government officials it deems responsible for the 2020 death of its Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC)-Qods Force Commander and designated foreign terrorist Qassem Soleimani,” DHS reported earlier this year.43 And Iran appears to have the potential capability to do so as well. In late May of this year, shortly before the Israel-Iran war began, FBI agents arrested Sharon Gohari, a naturalized U.S. citizen from Iran living in New York, on his return from a trip to Iran on charges of allegedly receiving child sexual abuse material.44 According to the Department of Justice, Gohari is also a “professional alien smuggler” who is suspected of soliciting and receiving payment from Iranian nationals and others to smuggle people into the United States.45 In one case, Gohari allegedly smuggled an Iranian national into the country who admitted that he had “previously completed tasks in Iran and Malaysia” for the IRGC.46 The case, first reported by Court Watch,47 led law enforcement to request that Gohari be detained pending trial.48

Recognizing the potential threat, President Trump posted to social media after the June 2025 U.S. airstrikes that “ANY RETALIATION BY IRAN AGAINST THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA WILL BE MET WITH FORCE GREATER THAN WHAT WAS WITNESSED TONIGHT.”49 In an effort to distance Iran from plots against the United States and its allies, and mitigate the risk of retaliatory attacks against Iran, Iranian agents have taken to hiring criminal proxies to carry out attacks at Tehran’s behest.

Criminal Surrogates

Following the failed 2018 Iranian bomb plot outside of Paris and the arrest and conviction of its organizer, Assadollah Assadi, Iranian operatives pivoted away from relying on Iranian nationals to carry out attacks in favor of hiring criminals to carry out attacks at Tehran’s behest.50

In 2022, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted51 IRGC operative Shahram Poursafi for running a murder-for-hire plot targeting former senior U.S. officials John Bolton52 and Michael Pompeo.53 Poursafi appears to have planned a series of attacks, telling the person he recruited to carry out the murders—someone he thought was a criminal for hire but who was actually working for the FBI—that he should first focus on killing Bolton but “then there would be other jobs” and the two “had years of work to do together.”54

European officials expressed grave concern over Iran’s use of criminal proxies to carry out attacks there, as well. The director of MI5 in the United Kingdom revealed in October 2024 that over the previous two and a half years, U.K. authorities had tracked 20 Iranian-backed plots targeting U.K. citizens and residents.55 “Iranian state actors make extensive use of criminals as proxies – from international drug traffickers to low-level crooks,” he added.56 “The Iranian regime’s use of criminal networks as terrorist proxies in Europe poses a grave threat to our internal security,” the European Commission reported that same year, following accounts from Swedish authorities that Iran had contracted Swedish gangs to carry out attacks there.57

U.S. officials noticed a similar trend. In early 2024, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated Iranian narcotics trafficker Naji Ibrahim Sharifi-Zindashti for operating a “network of individuals that targeted Iranian dissidents and opposition activists for assassination at the direction of the Iranian regime,” specifically at the behest of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS).58 For example, Zindashti’s network recruited two Canadian Hell’s Angels bikers to assassinate individuals in the United States who had fled Iran, including an Iranian defector.59 According to the Treasury Department, “the MOIS and Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) have long targeted perceived regime opponents in acts of transnational repression outside of Iran, a practice that the regime has accelerated in recent years,” including in the United States.60 In the wake of the Israel-Iran war, the European Union designated Zindashti and members of his network for serious human rights violations and transnational repression linked to these plots around the world.61

Undeterred by the exposure of the network that planned to kidnap Masih Alinejad, Iranian Revolutionary Guard general Ruhollah Bazghandi hired members of an Eastern European organized crime group to murder Alinejad in Brooklyn, New York.62 One operative was arrested in July 2022 near Alinejad’s home with a loaded automatic weapon in his car shortly after conducting surveillance of her and her home.63 He later testified against two other members of the organized crime group who were convicted in the murder-for-hire case in March 2025.64

Last year, Asif Merchant, a Pakistani operative working for Iran, tried to hire hitmen who were actually undercover law enforcement officers65 to assassinate then-presidential candidate Trump, among other political or government officials.66 This was not intended to be a one-off relationship, Merchant told a confidential law enforcement source, but would be ongoing and involved other criminal activities, such as planning protests and stealing documents or USB drives from a target’s home.67

Even in the midst of the 12-day Israel-Iran war, Iran reportedly reached out to organized crime groups in Europe, such as Foxtrot in Sweden, pressing them to quickly carry out attacks targeting Israeli and American interests there.68 But the cost of taking on such contracts increases for organized crime groups as authorities around the world focus their intelligence and law enforcement agencies on potential Iranian threats. Terrorist proxies, however, are more likely to be motivated to act in Iran’s interests given that their interest is ideological, not just financial.

Terrorist Proxies

Historically, Iran has used terrorist proxies to carry out attacks at its behest—on their own, or working together with Iranian agents—around the world.69 While Hezbollah has never carried out an attack within the United States, the group has long had networks of operatives and supporters living across the country, some of whom carried out preoperational surveillance for potential future attacks in the homeland.70

“Hezbollah has maintained a presence in the United States since at least 1987,” according to the FBI.71 In 1994, the FBI reported that a Hezbollah cell in New York was divided into teams to protect operational security and Hezbollah matters could not be discussed outside of a member’s team.72 It further noted that members of a Hezbollah cell on the West Coast initiated a neighborhood watch program to alert cell members if law enforcement officers came around.73 Hezbollah leadership in Lebanon would likely be wary of jeopardizing the relatively safe environment its operatives enjoy in the United States—where they primarily engage in illicit financial activities—by carrying out an act of terrorism in the homeland, the FBI assessed at the time.74 But it then added this caveat: “However, such a decision could be initiated in reaction to a perceived threat from the United States or its allies against Hezbollah interests.”75 In 2002, the FBI went further still, reporting that “FBI investigations to date continue to indicate that many Hezbollah subjects in the United States have the capability to attempt terrorist attacks here should this be a desired objective of the group.”76

Over time, Hezbollah cells in major American cities—places such as New York, Houston, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Boston—became aware of FBI surveillance of their activities.77 In response, a former head of the FBI’s Iran-Hezbollah unit explained, “Hezbollah started placing operatives in areas such as Portland, Oregon; Louisville, Kentucky; and these operatives were to blend into the community and establish, essentially, sleeper cells to be activated, to conduct whatever activities Hezbollah may want of them.”78

Fast forward to June 2017, when the FBI arrested two Hezbollah operatives—Ali Kourani in New York and Samer el-Debek in Michigan—both members of Hezbollah’s Islamic Jihad Organization terrorist unit.79 One of the FBI agents who met with Kourani recalled that the then-suspect “sat back in his chair, squared his shoulders and stated, ‘I am a member of 910, also known as Islamic Jihad or the Black Ops of Hezbollah. The unit is Iranian-controlled.’”80

At his Hezbollah handler’s instruction, “Kourani carried out a variety of pre-operational intelligence-gathering missions in New York City, including conducting surveillance of FBI and U.S. Secret Service offices, as well as a U.S. Army armory.”81 “Kourani described himself as a Hezbollah sleeper agent, and carried out other operational activities in New York, such as identifying Israelis in New York who could be targeted by Hezbollah and finding people from whom he could procure arms that Hezbollah could stockpile in the area. Kourani told the FBI he believed his [Islamic Jihad Organization] IJO handler tasked him with identifying Israelis currently or formerly affiliated with the Israeli army ‘to facilitate, among other things, the assassination of IDF personnel in retaliation for the 2008 assassination of [IJO leader] Imad Mughniyeh.’”82

Kourani also carried out surveillance at New York’s JFK and Toronto’s Pearson international airports and provided Hezbollah with detailed reports regarding “airport security procedures, the uniforms worn by security officials, and locations of cameras, security checkpoints, and other security barriers. At trial, prosecutors concluded that Hezbollah wanted this information because the group was ‘thinking about how to get terrorists, and weapons, and contraband through airports, from Lebanon into Canada, from Lebanon into the United States.’”83 In 2019, Kourani was convicted and sentenced to 40 years in prison for his covert terrorist activities on behalf of Hezbollah.84

For his part, el-Debek appears to have pleaded guilty and cooperated with U.S. authorities and was never put on trial.85 Described as a Hezbollah bomb maker, el-Debek carried out Hezbollah missions around the world, including cleaning up precursor explosives at a bomb-making safe house in Thailand and carrying out surveillance of U.S. and Israeli embassies and other potential targets in Panama.86

A few years later, another Hezbollah operative, Alexei Saab, would be convicted of receiving military-type training from Hezbollah and other crimes.87 According to the Department of Justice, he too carried out extensive preoperational surveillance of potential targets, including the United Nations headquarters, the Statue of Liberty, Rockefeller Center, Times Square, the Empire State Building, and local airports, tunnels, and bridges, and provided detailed information on these locations to Hezbollah.88 “In particular,” authorities noted, “Saab focused on the structural weaknesses of locations he surveilled in order to determine how a future attack could cause the most destruction.”89

Kourani, as mentioned, described himself as a sleeper agent and informed the FBI in 2016 that “there would be certain scenarios that would require action or conduct by those who belonged to the cell.”90 Kourani said that the U.S. sleeper cell would expect to be called upon to act if the United States ever went to war with Iran, or if the United States were to target Hezbollah, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, or Iranian interests. Kourani added, “in those scenarios the sleeper cell would also be triggered into action.”91 All these lines have now been crossed.

One case suggests Hezbollah may have already come close to triggering such action. In 2015, a Hezbollah operative in Houston was caught stockpiling ice-packs for the ammonium nitrate they contain, accumulating 300 pounds of the explosive precursor at the behest of the group.92 Robert Assaf pleaded guilty to lying to investigators about this activity and agreed to cooperate with investigators.93 The case suggests that Hezbollah sought and obtained hundreds of pounds of explosive precursor materials capable of producing multiple explosive devices in the United States.

All these cases, however, were thwarted by authorities, which suggests that Iran may increasingly seek to mobilize inspired lone offenders—who are much harder for law enforcement agencies to detect94—to carry out attacks, especially in the near term.

Inspired Lone Offenders

Authorities are concerned that individuals with no actual ties to Iran or its criminal or terrorist proxies could be radicalized by events abroad, for which they hold the United States responsible, and carry out acts of violence in the U.S. homeland.

In the terrorism advisory bulletin issued about the potential for Iranian reprisal strikes, DHS noted that Iran “publicly condemned direct U.S. involvement in the conflict,” adding that the Iran war could “motivate violent extremists and hate crime perpetrators seeking to attack targets perceived to be Jewish, pro-Israel, or linked to the US government or military in the Homeland.”95 This would become more likely, DHS assessed, in the event that Iranian leadership were to issue a religious ruling calling for retaliatory violence against specific targets in the U.S. homeland.96

In fact, according to U.S. law enforcement authorities, Iranian information operations targeting the homeland are not new. “Over the last year,” the Department of Homeland reported in October 2024, “Iranian information operations have focused on weakening US public support for Israel and Israel’s response to the 7 October 2023 HAMAS terrorist attack. These efforts have included leveraging ongoing protests regarding the conflict, posing as activists online, and encouraging protests.”97 New York City police went on heightened alert in the context of the war with Iran, despite the lack of any specific threat to the city, because—in the words of Mayor Eric Adams—“you always want to be conscious of lone wolves.”98

U.S. authorities have been concerned about the prospect of Shia militant homegrown violent extremism (HVE) for several years now, predating even the January 2020 killing of Soleimani and the many Iranian plots targeting current and former U.S. officials that followed.99 Already in October 2018, the National Counterterrorism Center produced an unclassified analytical report on the subject, entitled “Envisioning the Emergence of Shia HVE plotters in the U.S.”100 The report noted there had been no confirmed cases of Shia HVE plots in the United States, but identified several catalyzing events—most of which have already come to pass—that would increase the likelihood of Shi`a HVE mobilization to violence:

U.S. military actions abroad against Iran, Hezbollah, or Shia militants Shia leaders and clerics call for violence in the United States

Israeli government or Sunni killing of Shia individuals Anti-Shia activity in the United States

While the United States has thankfully not experienced significant anti-Shi`a activity (though there has been some101), the other catalyzing events have all come to fruition. The United States killed Soleimani in January 2020,102 and Iranian leaders responded with threats of “severe revenge”103 for his death with plots targeting current and former senior U.S. officials, including President Trump.104 Israeli forces killed Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah105 in 2024 and many other senior Hezbollah leaders,106 as well as Iranian officials in strikes in Syria107 and more recently in Iran.

A year after Soleimani’s death, several U.S. traffic controllers in New York heard a threat over aviation frequencies in which unknown persons warned, “We are flying a plane into the Capitol on Wednesday, Soleimani will be avenged.”108 While the threat was deemed not credible, and it is not clear if the breach of aviation frequencies was the work of Iranian agents or lone offenders, it underscored the threat posed by Iran and its proxies and supporters.

Indeed, online digital ecosystems run by domestic Shi`a extremists already exist here in the United States with the aim of inspiring and mobilizing lone offenders to carry out acts of violence in the U.S. homeland. Such outlets are nurtured by the Iranian government, attack regime opponents, and are “openly seeding Tehran-approved tropes across a range of platforms,”109 as Mustafa Ayad and this author concluded in a study on the subject.110 One such network, dubbed Pure Constellation, has managed 20 websites supportive of Iran and its proxies. Administered by an LLC registered at different times in Michigan and Georgia, the websites link to Telegram channels, WhatsApp groups, and social media sites such as Facebook and X.

A key theme in Pure Constellation’s online presence is the veneration of “martyrs,” many of them linked to the IRGC and its Middle East proxies. Pure Constellation aggressively helps spread English-language messages, wills, books, and biographies through a website dedicated to martyrs.111 The site describes itself as making “a humble attempt” to introduce martyrs because “a martyr is a true inspiration for all and, through his/her martyrdom, is capable of reviving a dead and decaying society from dark[ness] just like a candle that burns itself in order to provide light to those around it.”112

In January 2023, Iranian officials marked the anniversary of Soleimani’s death with a series of public statements threatening retaliatory attacks. Iran’s state-affiliated media released a list of 51 Americans accused of playing some role in the Soleimani operation, warning that they were “under the shadow of retaliation.”113 Speaking on the occasion, however, Maj. Gen. Mohammad Bagheri—then-chairman of Iran’s Armed Forces General Staff, who was killed in an Israeli airstrike during the recent war114—focused not on what Iranian agents might do, but on how angry youths inspired by the regime might act on their own. “Revenge against the masterminds and perpetrators of General Soleimani’s assassination will never be removed from the agenda of the youths of the Muslim world and his devotees across the world,” Bagheri asserted.115

A Multilayered Threat with a Long Tail

Iran may seek to carry out reprisal attacks in the United States, as it already has tried to do in Europe,116 targeting U.S. officials, Iranian dissidents, Israelis, or Jews. U.S. authorities assess the war with Iran created a “heightened threat environment in the United States,”117 and warned118 of potential cyber or terrorist attacks in light of calls119 by foreign terrorist organizations for attacks and Iran’s own threat to activate sleeper cells in the United States. If there were ever a time Iran would want to activate its homeland option,120 this would be it. But even if the next few weeks pass without any attack, the threat will persist.

Iran took its time preparing plots to avenge the death of Soleimani, and while all such plots have so far been thwarted, Iran continues to pursue plots to avenge his killing. The damage Israel and the United States inflicted on the regime in Tehran in the context of the recent war overshadows even the loss of Soleimani. Many senior Iranian officials and nuclear scientists were killed, Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs were bombed extensively, and the standing of Iran’s security services was severely undermined by their very public penetration by Israeli intelligence. It would be dangerous and hubristic to underestimate the anger Iranian regime figures must be experiencing now, and their commitment to retaliate for their embarrassing losses.

As a window into the regime’s commitment to retaliatory action, a slick propaganda video Iran’s security services produced to mark the third anniversary of Soleimani’s death in January 2023 is telling. Posted on the Sepahcybery Telegram account (Sepah is a reference to the IRGC), the video opens with a view of a small office and zooms in on a file on Soleimani’s death along with photo, and a magnifying glass sitting on the desk next to a cup of coffee.121 The date of the airstrike that killed him, January 3, is circled and marked with an ‘x’ in red on a desk calendar. Next, the camera hones in on a corkboard with photos and reports connected with red string attached to thumbtacks. The effect is to depict a network exposed in some investigation as being behind the Soleimani strike. The camera first zooms in on a photo of President Trump, the red string connecting his photo to those of other former U.S. government officials, including former National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, and about a dozen others. The picture fades, the music crescendos, and text appears on a black screen: “The perpetrators of general Soleimani’s martyrdom will be punished for their actions.”

The threats are clear as a series of images appear against a background of staccato music.122 An Iranian drone, followed by Trump golfing. A sniper rifle, then Robert O’Brien in front of a government building. An explosive detonator, then a clip of former Deputy National Security Advisor Matthew Pottinger. Clips of a knife, a syringe, a handgun with a silencer, a vile of poison, are interspersed with pictures of General Mark Milley, Keith Kellogg, General Richard Clarke, General Andrew Poppas, Lt. Gen Joseph Guastella, Gen. James Slife, Gen. James Holmes, Victoria Coates, and Lt. Gen. Scott Howell.

“We will determine how and when to punish,” reads a text that follows, followed by crime scene tape, images of various crime scenes, first responders in hazmat suits, blood-stained chairs, and ambulances.123 The camera zooms in on the corkboard, where the faces on each of the photos are now crossed out in red ink. The words “coming soon…” appear on a black screen, followed by the logo124 of the IRGC. U.S. authorities take the threat of Iranian retaliatory attacks very seriously, and this warning, though a few years old and propagandist, is worth heeding. If Iran fails to carry out an attack using its own agents, criminal or terrorist proxies, or inspired lone offenders, it will not be for lack of trying.

Conclusion

Tough talk aside, Iran has a stronger track record of plotting attacks than of successfully executing them. Counterterrorism agencies around the world have successfully thwarted most Iranian plots, whether targeting an Iranian dissident or President Trump, often based on tips received from Israeli intelligence. And yet, the terrorists only have to get it right once to be successful, while counterterrorism officials have to get it right every single time to avoid catastrophic failure.

In the early years after the Iranian revolution, Iranian agents boasted a nearly 80 percent operational success record, based on the author’s dataset of Iranian external operations.125 From 1979 to 1988, Iran and its agents executed 11 successful external operations out of a total of 14 (a 78.5 percent success rate). But as counterterrorism capabilities developed over the years, Iran’s success rate dropped precipitously. Over the past 10 years, Iran and its agents executed 47 successful external operations out of a total of 191 (a 24.6 percent success rate).

Successful operations have deadly consequences, and even those that are unsuccessful force authorities to allocate limited resources to thwart the next one. Examples of recent Iranian plots that succeeded include the abduction and murder of Rabbi Zvi Kogan in the UAE by Uzbek assailants in November 2024;126 a teenager firing a gun at the offices of Elbit Systems in Sweden at the behest of a criminal organization hired by Iran in 2024;127 and incendiary devices thrown at the entrance to the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) office in Paris in 2023.128

While no spectacular Iranian plots succeeded in recent years, the pace of these threats has increased, and authorities remain very concerned Iranian operatives and their agents will continue to attempt attacks. In a joint statement in July 2025, 14 Western countries came together to “condemn the growing number of state threats from Iranian intelligence services” in their respective countries. “We are united in our opposition to the attempts of Iranian intelligence services to kill, kidnap, and harass people in Europe and North America in clear violation of our sovereignty,” the statement reads, adding that Iranian services “are increasingly collaborating with international criminal organizations to target journalists, dissidents, Jewish citizens, and current and former officials in Europe and North America. This is unacceptable.”129 The same day that this statement was released, the Israeli National Security Council renewed a travel warning for Israelis in the UAE, noting that Iranian and other extremists are “driven by heightened motivation to exact revenge following Operation Rising Lion,” the 12-day war with Iran, and the Gaza war with Hamas.130

Iran will surely seek to avenge its losses in its 12-day war with Israel, and it will likely look to settle the score with the United States as well, given the U.S. airstrikes that targeted the Fordow nuclear complex. Iran’s intent to do harm is clear, but its capability to successfully carry out attacks—in particular spectacular ones—is less clear. The concern is that if Iranian operatives and their agents keep up the frenetic pace of operations, some might succeed.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News