Damascus, Syria – Since last July, the question of Syria’s Suweida province has entered a new phase. There is no longer talk of negotiations with the Damascus government, nor plans for the surrender of weapons.

Instead, the dominant theme among some of the province’s leaders has become secession from Syria and establishing an independent, Israeli-protected state.

Hikmat al-Hijri, the spiritual leader of the Druze community in Suweida, told Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth earlier this month that Syria is heading toward fragmentation and the creation of semi-autonomous regions.

In his view, this is the only path to securing the future of minorities and ensuring stability in the Middle East, with Israel being the only party “capable of guaranteeing any future arrangements in the region”.

This is not the first time al-Hijri has called for Suweida’s secession. In August, he urged international support for the province’s independence, calling on the world to help protect the Druze community.

This came in the aftermath of a week of clashes starting on 13 July between Druze fighters and Bedouin militias, which escalated into deadly confrontations involving government forces and other tribal fighters. More than 1,600 people were killed, including a large number of Druze civilians.

The debate over secession represents a broader crisis facing Syria’s religious minorities in the post-Assad era, as the new government struggles to assert authority over a fractured nation while facing accusations of sectarian violence.

Suweida, home to roughly half a million people, is the largest Druze stronghold in the world, and its fate could set a precedent for other minority communities weighing their options between integration, autonomy, or foreign protection.

A history of resistance

Salman Katbeh, a Druze activist residing in Jaramana, told The New Arab that even though the scale of crimes and massacres committed against civilians in Suweida was horrific, clearly there are parties with “certain agendas who exploited what happened to push the situation to the extreme”.

He notes that the secession demands being discussed would sever Suweida from its long national history.

“Syria achieved independence through the efforts of all segments of the Syrian people, particularly those from Suweida, who played a principal role and participated in every phase of the national struggle,” he added.

“What do we tell the families of martyrs who fell in the revolution against the French, or those who died in the October War and other battles?”

The Druze community of Suweida has a long history of resistance to foreign domination and authoritarian centralism, dating back at least to the early 20th century.

Sultan al-Atrash, the most iconic figure in modern Druze history, first clashed with French colonial forces in 1922 and later led the Great Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927, challenging French rule in Syria.

He also mobilised Druze and Syrian volunteers to fight against the establishment of Israel and in defence of Palestinian rights during the 1948 war.

But despite the long and intertwined history, it seems that the sentiment of independence has been slowly gaining traction.

An existential rupture

Ibrahim al-Khatib, a political activist based in Suweida, told The New Arab that the Druze are justified in their demand for independence, especially after suffering “massacres that amount to genocide”.

“The methodology, repetition, and execution of July’s massacres show that there was an intent to annihilate the Druze and break their national will,” he told TNA. “All those who were killed were civilians, and there was no significant military force confronting the authorities.”

Al-Khatib said that the massacres deeply affected the collective consciousness of Suweida’s residents, prompting them to demand secession from the Syrian state. He noted that the majority of the province’s population refuses to coexist with the current authorities in any form, calling instead for Suweida’s fate to be determined independently, whether through independence or autonomy.

Any semblance of agreement between Suweida’s Druze and the government, the activist argued, had been severed, with anger further fuelled by the authorities’ praise of tribes responsible for the violations and the formation of a token investigation committee.

“Who will the authority hold accountable? A soldier executing orders, or the commanders who led the campaign and were promoted to higher positions?” He asked.

“We are pursuing the demand for independence with all our strength and working toward it because it is an existential demand, not just a political one. We believe that living with the current authority means our death and physical liquidation.”

The shadow of Israel

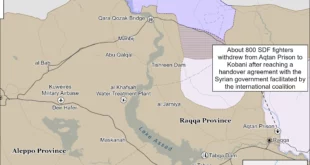

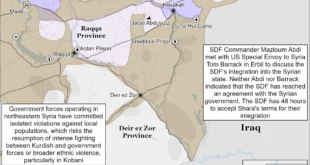

Despite the Syrian government’s significant military successes in the north and east against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), al-Hijri remains committed to his plans.

A source with ties to al-Hijri’s factions described the government’s northern campaign as a “setback for the ‘Bashan State’ project” that al-Hijri seeks to establish in Suweida.

Critics of al-Hijri argue that any attempt to separate Suweida from Syria would fail, citing anticipated US support for the Syrian government’s territorial integrity.

A Druze activist based in Suweida, who requested anonymity for security purposes, explained to The New Arab that talk of secession began before the massacres but became more explicit afterwards.

“These people forgot that Israel could have prevented the massacres from happening in the first place if it had wanted to, rather than stopping them after 34 villages were occupied, their residents displaced, and more than 1,500 people killed,” she told TNA.

“They also forgot Israel’s criminal role in the genocide in Gaza.”

In 2025, for the first time in 50 years, Druze religious leaders from Syria crossed into the Israeli-controlled Golan Heights through the UN-monitored buffer zone. This signalled a dramatic shift in Israel’s approach to the frontier, as it increasingly positioned itself as a protector of minorities in southern Syria, while simultaneously expanding its military presence beyond the ceasefire buffer zone established after the 1973 October War.

Israel’s incursions, military outposts on Mount Hermon, and repeated airstrikes in southern Syria are framed publicly as protection for Druze communities, but critics within the community note that Israel’s primary goal is securing its border, not the welfare of the Druze.

“In any case,” the activist continues, “despite all attempts to promote the idea of secession and complete independence, it does not represent the actual desire of Suweida’s residents. As months passed and people regained the compass they lost to fear, the voices demanding secession have noticeably receded.”

Al-Khatib argues, however, that Israel’s interests align with Suweida’s aspirations.

“There is no direct Israeli push for this; their interests intersect with our desire, and perhaps American interests will intersect in the future,” he says.

“The current authority pushed us into Israel’s arms. Not a single Arab country, neither neighbouring nor regional, defended our people, even with a word.”

Katbeh believes that Israel does not genuinely support Suweida but instead leverages the province as a bargaining tool to extract concessions from the Syrian authorities in ongoing security negotiations.

“When things reach their end, and a security agreement is signed, Israel will abandon this card,” he says, adding that international consensus favours a unified Syria, which he believes serves the country’s long-term interests.

But he contends that resolving Suweida’s situation requires measures that heal communal rifts and reintegrate the province peacefully into the state, with some form of administrative decentralisation, while ensuring redress, the return of displaced residents, and accountability for all crimes committed against civilians.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News