Lebanon’s Daily Star newspaper woke up in a good mood on Tuesday morning, declaring “Ray of hope shines on Beirut as both sides see ‘open door’ ” on its front page as hopes grew that simmering sectarian tensions would abate.

Lebanon’s Daily Star newspaper woke up in a good mood on Tuesday morning, declaring “Ray of hope shines on Beirut as both sides see ‘open door’ ” on its front page as hopes grew that simmering sectarian tensions would abate.

At 9am that day, bombs ripped through two minibuses near the mountain home of the Gemayel clan, Lebanon’s leading Christian political dynasty. The blasts killed three people and injured 20.

A day later, as a crowd of tens of thousands gathered in Beirut to commemorate the second anniversary of the murder of former prime minister Rafiq Hariri, the ray of hope looked like a flash in the pan.

Although no one claimed responsibility for Tuesday’s attack, it is widely seen as an attempt to disrupt efforts to ease a tense two month-long sectarian stand-off in Beirut.

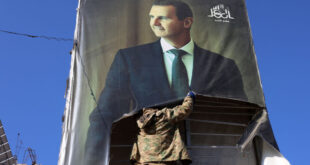

For supporters of Prime Minister Fouad Siniora, the timing and target of the bombings implicate Syria, five of whose Lebanese enemies — including Mr Hariri and industry minister Pierre Gemayel — have been murdered in the past two years.

They believe that Mr Hariri, the leader of Lebanon’s moderate Sunni Muslims and one of the Arab world’s wealthiest magnates — was killed on February 14, 2005, for backing a campaign to end two decades of Syrian military hegemony in Lebanon.

Ironically, the domestic and Western backlash against the massive blast that killed Mr Hariri and 22 others in downtown Beirut forced Damascus to withdraw its troops two months later. But the assassinations of anti-Syrian politicians and journalists have continued.

Lebanon’s Daily Star newspaper woke up in a good mood on Tuesday morning, declaring “Ray of hope shines on Beirut as both sides see ‘open door’ ” on its front page as hopes grew that simmering sectarian tensions would abate.

At 9am that day, bombs ripped through two minibuses near the mountain home of the Gemayel clan, Lebanon’s leading Christian political dynasty. The blasts killed three people and injured 20.

A day later, as a crowd of tens of thousands gathered in Beirut to commemorate the second anniversary of the murder of former prime minister Rafiq Hariri, the ray of hope looked like a flash in the pan.

Although no one claimed responsibility for Tuesday’s attack, it is widely seen as an attempt to disrupt efforts to ease a tense two month-long sectarian stand-off in Beirut.

For supporters of Prime Minister Fouad Siniora, the timing and target of the bombings implicate Syria, five of whose Lebanese enemies — including Mr Hariri and industry minister Pierre Gemayel — have been murdered in the past two years.

They believe that Mr Hariri, the leader of Lebanon’s moderate Sunni Muslims and one of the Arab world’s wealthiest magnates — was killed on February 14, 2005, for backing a campaign to end two decades of Syrian military hegemony in Lebanon.

Ironically, the domestic and Western backlash against the massive blast that killed Mr Hariri and 22 others in downtown Beirut forced Damascus to withdraw its troops two months later. But the assassinations of anti-Syrian politicians and journalists have continued.

Syria’s opponents in Lebanon — represented by Mr Siniora’s ruling coalition of moderate Sunni Muslims, Druze Muslims and Maronite Christians — believe that Damascus is now trying to both claw back some of its former influence and to stymie a United Nations investigation into the assassinations.

The continuing decline of America’s prestige in the Middle East, which severely weakened the pro-Western Siniora Government, is seen as a major factor in Syria’s new assertiveness.

The current crisis pits anti-Syrian government supporters against an opposition block led by Hezbollah, a Shiite Muslim group backed by Syria and Iran, and including a sizeable breakaway faction of Maronite Christians led by General Michel Aoun.

Since early December, supporters of Hezbollah and General Aoun have been camped outside the Prime Minister’s office — albeit in dwindling numbers — accusing him of collaborating with the US and Israel and demanding the Government resign.

Syria’s opponents in Lebanon — represented by Mr Siniora’s ruling coalition of moderate Sunni Muslims, Druze Muslims and Maronite Christians — believe that Damascus is now trying to both claw back some of its former influence and to stymie a United Nations investigation into the assassinations.

The continuing decline of America’s prestige in the Middle East, which severely weakened the pro-Western Siniora Government, is seen as a major factor in Syria’s new assertiveness.

The current crisis pits anti-Syrian government supporters against an opposition block led by Hezbollah, a Shiite Muslim group backed by Syria and Iran, and including a sizeable breakaway faction of Maronite Christians led by General Michel Aoun.

Since early December, supporters of Hezbollah and General Aoun have been camped outside the Prime Minister’s office — albeit in dwindling numbers — accusing him of collaborating with the US and Israel and demanding the Government resign.

Â

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News