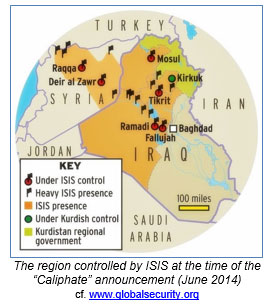

On the first day of the 2014 Muslim holy month of Ramadan, the Syrian anti-Assad group called the “Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS)”[1] announced that it would be establishing a caliphate[2], or Islamic State (IS, which also became the organization’s new name), on the territories it controls in Iraq and Syria. It also proclaimed the group’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, as caliph and “leader for Muslims everywhere”. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi would become the head of the state and would be known as “Caliph Ibrahim”.

In the message, titled “This Is the Promise of Allah”, the “Islamic State” declared the establishment of a caliphate “from Aleppo to Diyala”, and proclaimed that “it is incumbent upon all Muslims” to pledge allegiance to and support the “khalifah Ibrahim”.

The following themes were central to the argument framed to justify both this move and the assertion that Islamic State’s establishment of a caliphate nullifies the legality of “all emirates, groups, states, and organizations”:

o Succession: “the purpose for which Allah sent His messengers and revealed His scriptures, and for which the swords of jihad were unsheathed”. In this context, reference was also made to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s origins, referring to him as a member of the Prophet Muhammad’s Quraysh tribe, from which the dynasties of the Ummayad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates descended;

o Obligation: “…a wajib kifa’i (collective obligation) that the ummah sins by abandoning. It is a forgotten obligation… It is the khilafah (caliphate)”. In the tradition of the Salafi jihadist groups, the model evoked is that of the early Muslims who “abandoned nationalism and the calls of jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic ignorance), raised the flag of la ilaha ill Allah (there is no god but Allah) and carried out jihad in the path of Allah with truthfulness and sincerity”.

o Leadership: “Know that your leaders will not find any arguments to keep you away from the jama’ah (the body of Muslims united behind a Muslim leader), the khilafah, and this great good…” According to tradition, the existence of a caliphate compels the members of the ummah to acknowledge the caliph as the leader of Islam and IS’s message includes a warning for all other groups that “after this consolidation and the establishment of the khilafah, the legality of your groups and organizations has become invalid”. Moreover, therefusal to pledge loyalty to the caliph is considered apostasy.

The statement also lays out a radical vision for reconfiguring the Arab world. It is replete with injunctions from the Koran, several of which refer to God deputizing the “true believers” as his regents on earth, empowering them to humiliate and defeat his “enemies”, who now include Shi’a Muslims, democrats, nationalists, the Muslim Brotherhood, Jews and Christians. The Islamic State argues that all Muslims, including all jihadist factions, must acknowledge the caliph as their leader if they are not to live in sin. Though this notion of a collective religious obligation is largely consistent with traditional Islamic law, most Muslims consider such injunctions irrelevant in the modern age.

According to the U.S. State Department’s Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Iraq and Iran, Brett McGurk, ISIS is “a full-blown army” and “worse than al-Qaeda”, with a potential reach far beyond the Middle East. In a testimony on 24 July 2014, he said ISIS is “able to funnel 30 to 50 suicide bombers a month into Iraq. We assess these are almost all foreign fighters”. He also mentioned that “it would be very easy for ISIS to decide to funnel that cadre of dedicated suicide bombers – global jihadists – into other capitals around the region, or Europe, or, worse, here [in the United States]”.

ISIS aims to control at least the Sunni part of Iraq, and much of Syria and Lebanon. The emergence of a radical jihadist state in the heart of the Arab world would threaten the U.S. and American allies in the Middle East and Europe. In the long term, the Islamic State wants to be a global power, and, with the resources it is acquiring, the West and its allies face a difficult job to stop it.

Following the Caliphate announcement, ISIS engaged in several actions that shocked not only the Western but also the Muslim world, since they were directed against the Christians and the Muslims alike.

- Shortly after the declaration of the “caliphate”, on 18 July, after the Friday prayers, ISIS gave an ultimatum to the Christians in Mosul to convert to Islam, pay a tax (“jiziya”) or face death (which are the Koran requirements before waging jihad against the unbelievers). A similar action was taken by ISIS in February, in the Syrian city of Raqqa, calling on Christians to pay about half an ounce (14g) of pure gold in exchange for their safety.

- Before the Mosul ultimatum, the Islamic State marked Christian homes in Mosul with an “N” (for “Nazara”, meaning Christian). Until their forced exodus, Christians had been continuously present in Mosul for approximately 16 centuries.

- Soon after that, ISIS seized the Mar Behnam monastery near Mosul – a major Christian landmark and a place of pilgrimage which dates from the 4th century – and expelled the monks. The monks’ request to save some of the monastery’s relics was refused and they were allowed to leave only with their clothes. They walked for several kilometers before they were picked up by Kurdish fighters.

- On July 23, Islamic State militants blew up a revered Muslim shrine traditionally said to be the burial place of the prophet Jonah in Mosul. The militants first ordered everyone out of the Mosque of the Prophet Younis. The mosque was built on an archaeological site dating back to the eighth century BC and is said to be the burial place of the prophet, who is mentioned both in the Bible and the Koran and was a popular destination for religious pilgrims from around the world. The residents said that the militants claimed the mosque had become a place for apostasy, not prayer.

- At the beginning of July, some Middle East, Western and social media sites in Arabic reported about some tweets supposedly sent by Abu Turab Al-Maqdisi, a spokesperson for the ISIS, stating that the head of the ISIS, al-Baghdadi intends to destroy the Ka’ba, the holiest shrine to Islam (according to other sources, the tweets might have been placed by the Saudi intelligence in order to affect the reputation of the ISIS).

- At mid-July, reports also circulated that the Islamic State allegedly issued a fatwa ordering families in Mosul to have their daughters undergo female genital mutilation (FGM), in order to prevent “immorality” or face severe punishment. The accusations were even formulated by a senior UN humanitarian official, but supporters of the Islamic State dismissed the story as propaganda based on a fake document. Suspicions about its veracity were partly based on the fact that FGM is not required by Islam and is not prevalent in Iraq. It is widespread mostly in Egypt, Sudan and east Africa. However, residents of Mosul, as well as Kurdish officials, insisted it was true.

Setting up a caliphate ruled by the Sharia law has long been a goal of many jihadists. However, the recent declaration of a caliphate by ISIS is considered to be an unprecedented event in modern times. Regardless of the caliphate’s future, with ISIS violent jihadism is now an entrenched feature of the Arab political landscape.

As conceived in Islamic political thought, a caliphate, unlike a conventional nation-state, is not subject to fixed borders. Instead, it is focused on defending and expanding the dominion of the Muslim faith through jihad, or armed struggle.

1. Jihad in the Koran and the Muslim Jurisprudence

For at least a millennium, Muslims have disagreed about the meaning of jihad. The term may mean many things: the jurists’ warfare bounded by specific conditions, Ibn Taymiyya’s revolt against an impious ruler, the Sufi’s moral self-improvement, or the modernist’s political and social reform. The disagreement among Muslims over the interpretation of jihad is deeply rooted in the diversity of Islamic thought.

However, the term jihad should cause little confusion, for context almost always indicates what a speaker intends. The variant interpretations are so deeply embedded in Islamic intellectual traditions that the usage of jihad is unlikely to be ambiguous. An advocate of jihad as warfare indicates so through his goals. A Sufi uses the term mujahada or specifies the greater jihad. When ambiguity does exist, it may well be deliberate.

In the Koran, the term jihad it is normally found in the sense of fighting in the path of God; this was used to describe warfare against the enemies of the early Muslim community (ummah). In the hadith, the second most authoritative source of the Sharia (Islamic law), jihad is used to mean armed action, and most Islamic theologians and jurists in the classical period (the first three centuries) of Muslim history understood this obligation to be in a military sense.

In Arabic, jihad is a verbal noun with the literal meaning of “striving” or “determined effort”. The active participle of this verb, mujahid (plural mujahidin) means “someone who strives” or “a participant in jihad”. In many contexts, jihad means “fighting” (though there are other more specific words in Arabic that refer to the act of making war, such as qital or harb).

The term of Jihad, referring to a religious duty of Muslims, appears 41 times in 23 verses of the Koran, frequently in the idiomatic expression “striving in the way of God (al-jihad fi sabil Allah)”. Jihad is an important religious duty for Muslims. Some Sunni scholars even refer to this duty as the “sixth pillar” of Islam, though it occupies no such official status. In Twelver Shi’a Islam, however, Jihad is one of the 10 “Practices of the Religion”.

There are two commonly accepted meanings of jihad: an inner spiritual struggle and an outer physical struggle. The “greater jihad” is the inner struggle of a believer, in order to fulfill his religious duties. The “lesser jihad” is the physical struggle against the enemies of Islam. This physical struggle can take a violent form or a non-violent form.

The beginnings of Jihad are traced back to the words and actions of Prophet Muhammad and the Koran, which encourages the use of Jihad against non-Muslims. The Koran, however, does not use, for fighting and combat in the name of Allah, the term “jihad”, but the word “qital” (“fighting”). Jihad in the Koran was originally intended for the nearby neighbors of the Muslims, but as time passed and more enemies arose, the Koranic statements supporting Jihad were updated for the new adversaries.

In the Koran and in later Muslim usage, jihad followed by the expression fi sabil Illah (“in the path of God”), describes warfare against the enemies of the Muslim community. In the hadith[3] (the reports on the sayings and acts of the prophet, which is the second most important source of the Islamic law, Sharia), jihad means warfare. The majority of classical theologians, jurists, and traditionalists (specialists in the hadith) understood the obligation of jihad in a military sense.

The Islamic schools of thought/jurisprudence (Madhhab)

No Schools of Thought existed in Islam at the time of Prophet Muhammad and neither his practices nor his hadith (the Sunnah) were put in writing during his lifetime. After the death of the Prophet, many of the prominent Sahaaba (Companions of the Prophet) adhered to Imam Ali’s explanation of the Sunnah of the Prophet. The number of such personalities increased gradually, and they came to be known as the “Devotees of the teachings of the Prophet” as passed down by Ali. They were named Al‑Khaassah, meaning the elite, the distinctive, or the special. In Arabic they were referred to as Al‑Shi’a.

The rest of the Muslims were referred to as Al‑Aammah, meaning the general public or the common man and later as Al‑Jama’ah (the throng, the mass). About 150 years later, the term Jama’ah was modified to Al‑Sunnah wal Jama’ah. The term of Sunnah wal Jama’ah was prevalent during the 3rd century H[4], when the Schools of Thought in Islam were more or less consolidating.

Specifically, Shi’a Muslims (Shiites) follow only the Sunnah of Prophet Muhammad as passed down by Ahlul Bayt (the direct family of Muhammad) and the Fiqh laid down by Ahlul Bayt. Shi’a Muslims also believe in Imamah, the 12 Imams who were specified by Prophet Muhammad.

The Sunnis follow the Sunnah of Prophet Muhammad as passed down by the teachings of Sahaaba and Scholars after the Prophet and the Fiqh as laid by the head of the particular School of Thought (Madhhab). Sunnis do not believe in Imamah.

The main Islamic Schools of Thought are (in chronological order): Ja’fari (Ahlul Bayt), headed by Imam Al‑Saadiq, followed by the Shiites, and the four jurisprudence schools followed by the Sunni: Hanafi, founded by Abu Hanifa Al‑Na’maan; Maaliki, founded by Malik Ibn Anas; Shafi’i, founded by Ibn Idrees Al‑Shafi’i: Hanbali, founded by Ahmad Ibn Hanbal.

The Shi’a school of thought

For the first 150 years after the Prophet, the only evolving School of Thought was the Shi’a school as passed down by Imam Ali, and the chain of narration known as the Golden Chain of Narration, consisting of the direct lineage of Prophet Muhammad. This chain narrated hadith and explained Islam with each Imam referring the narration by way of his father directly up to the Prophet. The founder of this school, Imam Al‑Saadiq used to say “My narration is the narration of my father, and his is that of his father and so on, all going up to Ali who narrated directly from Prophet Muhammad”.

Those who followed this information were called “Shi’a Imamiyyah”, because of their belief in the 12 Imams from the Ahlul Bayt (the direct family of Muhammad). They would acknowledge narrations by other sources, as long as those narrations were confirmed by Ahlul Bayt. Because of their refusal to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Khalifa or his government, Ahlul Bayt and their devotees were exposed to persecution.

The Shi’a school of thought was founded by Imam Ja‛far al-Saadiq, who was born in the 82 AH, during the Umayyad reign. He taught and spread Islamic sciences in the Prophet’s mosque, just like his forefathers did. He would relate traditions from his father, al-Baqir, who related them from his forefathers all the way up to the messenger of Allah. He gave 1000 jurisprudential verdicts and was ahead of the scholars of his time in Islamic sciences, for example theology, tafsir (exegesis) and everything else Muslims treasured. Some 4000 religious students are said to have learned traditions from him. Some of Imam al-Saadiq’s students became leaders of other schools of jurisprudence, such as Abu Hanifah (the leader of the Hanafi school) and Imam Malik bin Anas (the leader of the Maliki school).

The Ahlul-Bayt (Shi’a) jurisprudential school has spread to different areas of the Islamic world, such as Iraq, Lebanon, Iran, Pakistan, Indonesia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, India, Azerbaijan, etc.

The Hanafi School (Hanafiyyah)

The Hanafi School is the first of the four orthodox Sunni schools of law. It is distinguished from the other schools because it relies less on mass oral traditions as a source of legal knowledge. It developed the exegesis of the Koran through a method of analogical reasoning known as Qiyas. It also established the principle that the universal concurrence of the Ummah (community) of Islam on a point of law, as represented by legal and religious scholars, constituted evidence of the will of God. This process is called ijma’, which means the consensus of the scholars. Thus, the school definitively established the Koran, the Traditions of the Prophet, ijma’ and qiyas as the basis of Islamic law. In addition to these, Hanafi accepted local customs as a secondary source of the law.

The Hanafi School of law was founded in Kufa (Iraq) by Imam Abu Hanifah al-Nu’man b. Thabit (80 – 148 AH). It derived from the bulk of the ancient school of Kufa and absorbed the ancient school of Basra. Abu Hanifah belonged to the period of the successors (tabi’in) of the Sahaabah (the companions of the Prophet). He was a Tabi’i himself, since he lived while some of the Sahaabah were still alive. Having originated in Iraq, the Hanafi School was favored by the first Abbasid caliphs, in spite of the school’s opposition to the power of the caliphs. The privileged position which the school enjoyed under the Abbasid caliphate was lost with its decline. However, the rise of the Ottoman Empire led to the revival of the Hanafi. Under the Ottomans, the judgment-seats were occupied by Hanafites sent from Istanbul, even in countries where the population followed another Madhhab. Consequently, the Hanafi Madhhab became the only authoritative code of law in the public life and official administration of justice in all the provinces of the Ottoman Empire.

Nowadays, the Hanafi code prevails in the former Ottoman countries. It is also dominant in Central Asia and India. It is followed by the majority of the Muslim population of Turkey, Albania, the Balkans, Central Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, China, India and Iraq.

The Maliki School (Malikiyyah)

Malikiyyah is the second of the Islamic schools of jurisprudence. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas (93 – 179 AH), a legal expert in the city of Medina. Such was his stature that it is said three Abbasid caliphs visited him while they were on Pilgrimage to Medina. The second Abbasid caliph, al-Mansur, approached the Medinan jurist with the proposal to establish a judicial system that would unite the different judicial methods that existed at that time throughout the Islamic world.

Imam Malik’s major contribution to Islamic law is his book al-Muwatta (“The Beaten Path”). The Muwatta is a code of law based on the legal practices that were operating in Medina. It covers various areas ranging from prescribed rituals of prayer and fasting to the correct conduct of business relations. The legal code is supported by some 2,000 traditions attributed to the Prophet.

The school spread westwards through Malik’s disciples, becoming dominant in North Africa and Spain. In North Africa, Malikiyyah gave rise to an important Sufi order, Shadhiliyyah, which was founded by Abu al-Hasan, a jurist in the Malikite School, in Tunisia in the thirteenth century.

During the Ottoman period, when Hanafite Turks were given the most important judicial role in the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, remained faithful to its Malikite heritage. Such was the strength of the local tradition that qadis (judges) from both the Hanafite and Malikite traditions worked with the local ruler. Following the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Malikiyyah regained its position of ascendancy in the region. Today Malikite doctrine and practice remains widespread throughout North Africa, the Sudan and regions of West and Central Africa.

The Shafi’i School

The Shafi’i School (Shafi’iyyah) was the third school of Islamic jurisprudence, named after Muhammad ibn Idris al-Shafi’i (150- 206 AH), whose lineage traced back to Hashim, the son of ‛Abd al-Muttalib, the Prophet’s grandfather.

He belonged originally to the school of Medina and was also a pupil of Malik ibn Anas, the founder of the Maliki school of thought. However, he came to believe in the overriding authority of the traditions from the Prophet and identified them with the Sunnah.

Baghdad and Cairo were the chief centers of the Shafi’iyyah. From these two cities Shafi’i teaching spread into various parts of the Islamic world. In the tenth century, Mecca and Medina came to be regarded as the school’s chief centers outside of Egypt. Under the Ottoman sultans, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Shafi’i were replaced by the Hanafites, who were given judicial authority in Constantinople, while Central Asia passed to the Shiites as a result of the rise of the Safawids in 1501. In spite of these developments, the people in Egypt, Syria and the Hidjaz continued to follow the Shafi’i Madhhab. The Shafi’i gradually replaced the Maaliki Madhhab in Egypt, then spread in Palestine and Syria. Today it remains predominant in Southern Arabia, Bahrain, the Malay Archipelago, East Africa and several parts of Central Asia.

The Shafi’i School of Thought stands in‑between the Maaliki and Hanafi, in that it uses some of the ways from both these schools. Like other Sunni schools, the Shafi’i does not acknowledge the Imamah of Ahlul Bayt.

The Hanbali School (Hanbaliyyah)

The Hanbali School is the fourth orthodox school of law within Sunni Islam. It derives its decrees from the Koran and the Sunnah, which it places above all forms of consensus, opinion or inference. The school accepts as authoritative an opinion given by a Companion of the Prophet, providing there is no disagreement with another Companion. In the case of such disagreement, the opinion of the Companion nearest to that of the Koran or the Sunnah will prevail.

The Hanbali School of law was established by Imam Ahmad b. Hanbal (165 – 240 AH). He studied law under different masters, including Imam Shafi’i (the founder of the Shafi’i school). He is regarded as more learned in the traditions than in jurisprudence. His status also derives from his collection and exposition of the hadiths. His major contribution to Islamic scholarship is a collection of fifty-thousand traditions known as “Musnadul-Imam Hanbal”.

In spite of the importance of Hanbal’s work, his school did not enjoy the popularity of the three preceding Sunni schools of law. Hanbal’s followers were regarded as reactionary and troublesome, because of their reluctance to give personal opinion on matters of law, their rejection of analogy, their intolerance of views other than their own, and their exclusion of opponents from power and judicial office. Their unpopularity led to periodic bouts of persecution against them.

The later history of the school has been characterized by fluctuations in their fortunes. Hanbali scholars such as Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn Qayyim al-Jawzia did display more tolerance to other views than their predecessors and were instrumental in making the teachings of Hanbali more generally accessible.

From time to time, Hanbaliyyah became an active and numerically strong school in certain areas under the jurisdiction of the Abbassid Caliphate. But its importance gradually declined under the Ottoman Turks.

The emergence of the Wahhabi in the nineteenth century and its challenge to Ottoman authority enabled Hanbaliyyah to enjoy a period of revival. Modern-day Wahhabis also belong to the Hanbali school of law, albeit to a more puritanical version of it. Today the Hanbali school is officially recognized as authoritative in Saudi Arabia and areas within the Persian Gulf.

Jihad in the Islamic schools of jurisprudence

The four Sunni Islamic schools of thought (Madhhab) – Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i, and Hanbali – may differ in their interpretations of basic Islamic precepts, including Jihad, but they generally agree on the main issues of Islam.

Within classical Islamic jurisprudence, which began to be developed during the first centuries after the Prophet’s death, jihad is the only form of warfare permissible under Islamic law, and may consist in wars against unbelievers, apostates, rebels, highway robbers and dissenters from Islam. The primary aim of jihad as warfare is not the conversion of non-Muslims to Islam by force, but rather the expansion and defense of the Islamic state. Whether the Koran sanctions defensive warfare only or commands an all out war against non-Muslims depends on the interpretation of the relevant passages. This is because it does not explicitly state the aims of the war Muslims are obliged to wage.

The medieval theories included elaborate rules on the right conduct of jihad. No war was a jihad unless authorized and led by the imam, the leader of the Islamic state. Enemies were to be given fair warning, and, should they choose not to accept Islam or to fight, they were to be offered protected (dhimmi) status, which allowed them to retain communal autonomy within the Islamic state in return for tax payments. This provision initially applied to “People of the Book” (Christians and Jews) but later was broadened to include other religious communities living under Muslim rule. Noncombatants were not to be killed, nor was enemy property to be destroyed unnecessarily.

In addition to the expansionist jihad, medieval scholars also dealt with internal conflicts against rebels within Islam. In this form of jihad, stricter rules of engagement and greater protection for the lives and property of the enemy applied than in the case of non-Muslims. The aim of this type of jihad was to rehabilitate the rebels as quickly as possible into the Muslim body politic.

The Hanafi school mentioned in its Hidayah[5] that “it is not lawful to make war upon any people who have never before been called to the faith, without previously requiring them to embrace it, because the Prophet so instructed his commanders… If the infidels, upon receiving the call, neither consent to it nor agree to pay capitation tax, it is then incumbent on the Muslims to call upon God for assistance, and to make war upon them… the Prophet, moreover, commands us so to do”.

According to Ibn Abi Zayd al-Qayrawani, a 10th century Maliki jurist, Jihad is a precept of Divine institution. Malikis maintain that it is preferable not to begin hostilities with the enemy before having invited the latter to embrace the religion of Allah except where the enemy attacks first. They have the alternative of either converting to Islam or paying the tax (jiziya), short of which war will be declared against them.

Muhammad ibn Idris ash-Shafi’i, the founder of the Shafi’i school of thought, was the first to permit offensive jihad. However, he limited this warfare against pagan Arabs only, not permitting it against non-Arab non-Muslims.

The 11th century Shafi’i jurist Al Mawardi stressed the necessity to invite the infidels (mushikrun) to embrace Islam before engaging a war against them: for those “whom the call of Islam has reached, but they have refused it and have taken up arms”, …“the amir of the army has the option of fighting them… in accordance with what he judges to be in the best interest of the Muslims and most harmful to the mushrikun… Second, those whom the invitation to Islam has not reached… it is forbidden to…begin an attack before explaining the invitation to Islam to them… if they still refuse to accept after this, war is waged against them”…

The view of a restricted, defensive version of jihad was contested by Hanbali legal philosopher Taqi al-Din Ahmad Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328 AD)[6]. He declared that a ruler who fails to enforce Sharia rigorously in all aspects, including the conduct of jihad, forfeits his right to rule. Ibn Taymiyya strongly advocated and personally participated in jihad as warfare against both the Crusaders and the Mongols who then occupied parts of the Dar al-Islam.

He stressed that “since lawful warfare is essentially jihad and since its aim is that the religion is God’s entirely and God’s word is uppermost, therefore according to all Muslims, those who stand in the way of this aim must be fought”.

Ibn Taymiyya developed his outlook by building on a long tradition of dissidents in Islamic history who engaged in jihad against rulers they deemed insufficiently Muslim, including the Kharijis of the seventh century and the Assassins of the eleventh century. He also broke with the mainstream of Islam by asserting that a professing Muslim who does not live by the faith is an apostate (unbeliever).

By going well beyond most jurists (who tolerated rulers who violated Sharia for the sake of the community’s stability), Ibn Taymiyya laid much of the groundwork for the intellectual arguments of contemporary radical Islamists.

A world divided

For the Muslim jurists, jihad fits the context of a world divided into Muslim and non-Muslim zones, Dar al-Islam (Abode of Islam) and Dar al-Harb (Abode of War) respectively. This model implies perpetual warfare between Muslims and non-Muslims until the territory under Muslim control absorbs what is not Muslim. Extending Dar al-Islam does not mean the annihilation of all non-Muslims, however, nor even their necessary conversion. Indeed, jihad cannot imply conversion by force, for the Koran (2:256) specifically states “there is no compulsion in religion”. Jihad has an explicitly political aim: the establishment of Muslim rule, which in turn has two benefits: it articulates Islam’s defying other faiths and creates the opportunity for Muslims to create a just political and social order.

Islamic jurisprudence also divides the inhabitants of Dar al-Harb (known as harbis) into two: “People of the Book”[7] (Ahl al-Kitab) and polytheists. The People of the Book may live under Muslim rule so long as they accept a subordinate status (that of the dhimmi) which entails paying a tribute (jiziya) and suffering a wide range of disabilities. As for polytheists, the law requires Muslims to offer them the choice of Islam or death, though this was rarely followed after the initial Muslim conquest of Arabia.

The belief that jihad should continue until Dar al-Islam covers the entire world does not imply that the jurists expect Muslims to wage non-stop war. Although there is no mechanism for recognizing a non-Muslim government as legitimate, the jurists allowed the negotiation of truces and peace treaties of limited duration. The jurists provided for military prudence, permitting the withdrawal of badly outnumbered or overpowered forces. And some jurists added an intermediate category, Dar al-‘Ahd (Abode of Covenant) or Dar al-Sulh (Abode of Peace), for those countries where non-Muslim rulers govern non-Muslim subjects.

The dualist vision of the world divided in two intractably opposed domains is not uncommon. The ancient Greeks set themselves apart from the inferior “barbarians”, a term that referred to all non-Greeks, as did the pre-Islamic Arabs from the scorned ‘Ajam (non-Arabs). The Jews separated themselves from the impure goyim; the Christians from the unsaved “infidel”. The Cold War period saw the polarization of the world into pro-Western and pro-Soviet camps. More recently, U.S. President George Bush Sr. warned in the aftermath of 11 September, “you’re either with us or you’re with the terrorists”.

The Manichaean worldview has also found a theoretical support in Samuel Huntington’s provocative formulation of the “clash of civilizations”. Although his hypothesis mentions more than two civilizations potentially on a collision course with one another, the core conflict is between the monolithically conceived world of Islam and the West. In this conceptualization, Huntington may even be regarded as having breathed new life into the dichotomous abodes of peace and war, with the positions of Islam and the West transposed.

Jihad as base for development of Siyar (International Islamic law)

The role of the jurists and their conceptualization of Dar-al-islam and Dar-al-harb is significant, since these concepts are not of Koranic origin, but rather categories or classifications which were introduced as corollaries to their understanding of jihad. The concepts were also used in the Siyar, the Islamic international law that is part of the Islamic jurisprudence.

Abu Hanifa is believed to be the first Muslim Jurist to have used the term Siyar (which refers to international Islamic law). Al Shafi’i also referred to it in connection with the work of others. The very early works on Syiar dealt mainly with Jihad, which came to connote a struggle for the cause of God. The majority of the jurists of the classical period came to view jihad not only as a defensive struggle, but an aggressive one as well.

There is little difference between the Shi’a doctrine of jihad and that of the Sunni, except that the former stipulates that jihad can be only launched under the leadership of the Imam. In fact, one of the qualifications of the Imam is the ability to lead the jihad. For the Twelver Shiites, since the occultation of the twelfth Imam, strictly speaking, no jihad can be launched.

The concept of jihad made Muslim jurists develop the model of the world divided into Dar-al-Islam and Dar-al-harb. Dar-al harb was a place where there was no peace between Muslims and non-Muslims, although that did not mean actual fighting. Dar-al-harb was potentially Dar-al Islam and to actualize this jihad might be necessary.

It was also possible that part of Dar-al islam revert to Dar-al-harb. According to Abu Hanifa, that was possible under three conditions: (1) that the ordinances of Islam were suppressed in favor of those of the disbelievers, (2) the territory in question was contiguous with Dar-al-harb with no Muslim territory located between it and the Dar-al-harb and (3) there was no longer security for the Muslims in the Dar-al-harb.

Various papers on Syiar have been read at the annual conference of the Academy of Islamic research located at the al-Azhar university in Cairo, the first such conference being held in 1964. In 1968, the fourth conference was noteworthy in that a high percentage of the papers presented focused on jihad, aggression, human rights and international law and relations. During the 1968 event it was also stated that a jihad against Zionism was justified.

Sunni and Shi’a Interpretations of Jihad

Sunni and Shi’a Muslims agree, in terms of just cause, that jihad applies to the defense of territory, life, faith, and property; it is justified to repel invasion or its threat; it is necessary to guarantee freedom for the spread of Islam; and that difference in religion alone is not a sufficient cause. Some Islamic scholars have differentiated disbelief from persecution and injustice, and claimed that jihad is justified only to fight those unbelievers who have initiated aggression against the Muslim community. Others, however, have stated more militant views which were inspired by Islamic resistance to the European powers during the colonial period: in this view, jihad as “aggressive war” is authorized against all non-Muslims, whether they are oppressing Muslims or not.

The question of right authority (no jihad can be waged unless it is directed by a legitimate ruler) also has been divisive among Muslims. The Sunnis saw all of the Muslim caliphs (particularly the first four “rightly guided” caliphs to rule after the Prophet Muhammad’s death, who possessed combined religious and political authority) as legitimate callers of jihad, as long as they had the support of the realm’s ulama (Islamic scholars). The Shiites see this power as having been meant for the Imams, but wrongly denied to them by the majority Sunnis. The lack of proper authority after the disappearance of the 12th (the “Hidden”) Imam in 874 AD also posed problems for the Shiites: this was resolved by the ulama increasingly taking this authority for itself to the point where all legitimate forms of jihad may be considered defensive, and there is no restriction on the kind of war which may be waged in the Hidden Imam’s absence, so long as it is authorized by a just ruler (this idea reached its peak under Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini).

Both sects agree on the other prerequisites for jihad. Right intention (niyyah) is fundamentally important for engaging in jihad. Fighting for the sake of conquest, booty, or honor in the eyes of one’s companions will earn no reward; the only valid purpose for jihad is to draw near to God. In terms of last resort, jihad may be waged only if the enemy has first been offered the triple alternative: accept Islam, pay the jiziya (the poll tax required for non-Muslim “People of the Book” living under Muslim control), or fight.

Jihad as a non-violent process

Jihad means in Arabic “strive” or “struggle” and the concept of jihad in Islam encompasses the struggle against the temptation, the struggle against succumbing to one’s own desires and whims, the struggle against ignorance, and the struggle against oppressors. The struggle may be spiritual, intellectual, or physical.

This means that jihad can be achieved by peaceful means as well as by force. A well-established principle in Islamic jurisprudence is that struggle by force can only be performed by the state. Only the state can declare war. Furthermore, for a fight to be an act of jihad, it must pass muster on three criteria: justice of the cause, nobility of the means, and the intent of godliness.

Within Sunni Islam, Jihad has been classified either as al-jihad al-akbar (the greater jihad), the struggle against one’s ego or self, or al-jihad al-asghar (the lesser jihad), the external, physical effort, often implying fighting. A similar interpretation is also accepted by the Shi’a Islam.

The primary historical basis for this interpretation is a moment mentioned in the hadith in which Muhammad is reported to have told warriors returning home that they had returned from the lesser jihad of struggle against non-Muslims to a greater jihad of struggle against oneself. The hadith recounts how Muhammad, after a battle, said, “We have returned from the lesser jihad (al-jihad al-asghar) to the greater jihad (al-jihad al-akbar)”. When asked “What is the greater jihad?” he replied “It is the struggle against oneself”. Although this hadith does not appear in any of the authoritative collections, it has had enormous influence in Sufism.

The Sufi view also classifies Jihad into two parts: the “Greater Jihad” and the “Lesser Jihad”. Muhammad put the emphasis on the “Greater Jihad” by saying “Holy is the warrior who is at war with himself”. In this sense, external wars and strife are seen as a satanic counterfeit of the true “jihad”, which can only be fought and won within.

The Sufi doctrine develops from the “effort” sense of jihad, meaning an inward struggle directed against evil in oneself. Sufis understand the greater jihad as an inner war, primarily a struggle against the base instincts of the body, but also resistance to the temptation of polytheism.

By the eleventh century, Sufism had become an extremely influential form of Islamic spirituality. To this day, many Muslims conceive of jihad as a personal rather than a political struggle. But Sufism provoked opposition, most importantly from Ibn Taymiyya, who condemned many aspects of Sufism which he believed contradicted the Sharia. His disciple Ibn al-Qayyim al-Jawziya (1292-1350) explicitly condemned the doctrine of greater jihad, discarding as a deliberate fabrication the hadith that originates this concept.

The Sufi doctrine of greater jihad remained alive and, while less influential than Islamism in the political realm, it still has considerable impact on the spiritual life of Muslims. The importance of the Sufi outlook made Islamists like Hasan al-Banna repeat medieval criticisms of the greater jihad.

Dawa and Jihad in radical Islam

One form of Jihad, usually overlooked, is the Jihad of presenting the message of Islam (Dawa). Thirteen years of the Prophet’s 23-year mission consisted purely of this type of Jihad. Contrary to popular belief, the word Jihad and related forms of its root word are mentioned in many Makkan verses in a non-combative context.

Although it seems surprising, Dawa was a central concept in Ibn Abd al-Wahhab’s vision of an educational process designed to win converts to God through discussion and debate rather than violence and killing.

The purpose of jihad is the protection and increase of the Muslim community as a whole, not personal gain or glory. Ibn Abd al-Wahhab did not define jihad as an individual undertaking (fard ‘ayn) and his description of jihad was intended to set it apart from pre-Islamic military practices, particularly raiding. Ibn Abd al-Wahhab outlined three scenarios in which jihad is called for:

- When two opposing groups meet face to face until the other side retreats (Koran 8:45)

- When the enemy leaves its own territory, beginning with the enemies that are closer geographically

- When the imam calls for it. He emphasized that only the imam can declare jihad – this is not a prerogative of the political ruler. Wahhab also restricted the imam’s right to declare jihad by charging him not to deliberately incite his people to jihad because the motivation for doing so would be questionable. The intent of the imam is an important factor in determining whether the call for jihad is legitimate.

The Dawa-oriented forms of radical Islam are also to be found in the Western Muslim communities, where Dawa is usually interpreted as “re-Islamization” of Muslim minorities, seen as “oppressed brothers” who should be liberated. The groups focusing on Dawa follow a long-term strategy based on puritanical, intolerant and anti-Western ideas. They are propagating extreme isolation from Western society and encourage Muslims to (covertly) develop their own autonomous power structures based on specific interpretation of the Sharia law.

Radical Islam highlights the resistance against the Western political power, which should be broken and replaced by the political power of the Islam. A first step to that end is the Islamization of the political system in Muslim countries. The ultimate objective, however, is far more ambitious: the establishment of the universal caliphate (the universal Islamic state) and the Umma (the Islamic global community), a superpower capable of overruling the West.

Analysts also note a trend described as a “Puritanisation”, which is not primarily focused on establishing an Islamic state, but on the return of all Muslims to the “purity” of the early stages of Islam before it was “tarnished” by “heretical” influences from, for example, Shi’ism, Hinduism or Western thinking. Present-day radical-Islamic puritanism is more intolerant than traditional political Islam and has a much stronger anti-Western orientation.

Radical-Islamic puritans often call themselves “Salafists”: they wish to return to the pure Islam of the Salaf (the companions of Muhammad). Salafism has its roots in the reformers of the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, such as Afghani, Abduh and Ridah[8], who saw a return to the pure Islam of the first followers of Muhammad as the solution to the crisis in the Islamic world. Gradually, Salafism shifted towards more conservative and ultra-orthodox views, in particular under the influence of Saudi Wahhabism. Today, the terms Wahhabism and Salafism are often used as synonyms. However, it is preferable to reserve the term Wahhabism for the (mainly) Saudi variant of Salafism. Present-day (radicalized) Salafism is far removed from the original Salafiyya, which was championed by Afghani and Abduh. Present-day Salafists regard the “return to pure Islam” as excising everything what in their view has tarnished Islam. Also characteristic for many puritan Salafist groups is branding those who do not adhere to the Salafist principles (including other non-Salafist Muslims) as “heretics” (takfir).

In addition to organizations and networks concentrating on Dawa, there are others who focus on the jihad (in the sense of armed conflict). Some groups combine the two. The choice of Dawa-oriented groups for non-violent activities does not always imply that they are non-violent. Often they do not yet consider armed jihad expedient for practical reasons (because of the other side’s superiority) or for religious reasons (the jihad against nonbelievers is only possible when all Muslims have returned to the “pure” faith). Furthermore, Dawa-oriented groups often make ambiguous comments about the legitimacy of the armed Jihad in areas where Muslims are oppressed and persecuted. With the support of prominent Mullahs, they often implicitly approve of such a form of armed Jihad, although they are careful not to explicitly incite people to it.

There is now a spectrum of jihadi organizations that can be described as purely focused on violent jihad on a local or global level and that use Dawa as their main organizing principle, yet still utilize violence on a local or global level. There are also mixed cases in which neither violent jihad nor Dawa take precedence over the other. Some forms of radical Islam opt for Dawa, the long-term influencing strategy, not directly violent, while other forms of radical Islam focus on short-term strategies of violent activism and terrorism (Jihad). Jihad and Dawa may also be combined as two complementary strategies which, according to circumstances, are to be used either simultaneously or separately.

Modern interpretations of Jihad

The increasingly widespread rejection of Western civilization as a model for Muslims has been accompanied by a search for indigenous values that reflect traditional Muslim culture, as well as a drive to restore power and dignity to the community. The last 40 years have seen the rise of militant, religiously-based political groups whose ideology focuses on demands for jihad (and the willingness to sacrifice one’s life) for the forceful creation of a society governed solely by the Sharia and a unified Islamic state, and to eliminate un-Islamic and unjust rulers. These groups are also reemphasizing individual conformity to the requirements of Islam.

The causes of Islamic radicalism have been religious-cultural, political, and socio-economic and many Islamic groups blamed social ills on outside influences; for example, modernization (Westernization and secularization) has been perceived as a form of neocolonialism, an evil that replaces Muslim religious and cultural identity and values with alien ideas and models of development. In this context, scholars have succeeded in replacing the greater jihad, the fight against desires, with the lesser jihad, the holy war to establish, defend and extend the Islamic state.

The Muslim Brotherhood and “the Neglected Duty”

The Indian and later Pakistani thinker Sayyid Abu al-A’la Mawdudi (1903-1979) was the first Islamist writer to approach jihad systematically. Warfare, in his view, is conducted not just to expand Islamic political dominance, but also to establish just rule (one that includes freedom of religion). Mawdudi’s political life began after World War I, with his participation in the Khilafat movement of the Indian Muslims that, among other causes, supported Indian independence from Great Britain. For Mawdudi, jihad was akin to war of liberation, and is designed to establish politically independent Muslim states.

Mawdudi’s view significantly changed the concept of jihad in Islam and began its association with anti-colonialism and “national liberation movements”. His approach paved the way for Arab resistance to Zionism and the existence of the state of Israel to be referred to as jihad. In this spirit, the rector of Cairo’s Al-Azhar University would state, in the early 1970s that all Egyptians, Christians included, must participate in jihad against Israel.

The Egyptian Islamist thinkers and leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood Hasan al-Banna (1906-1949) and Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966) took hold of Mawdudi’s activist and nationalist conception of jihad and its role in establishing a truly Islamic government, and incorporated it with Ibn Taymiyya’s earlier conception of jihad that includes the overthrow of governments that fail to enforce the Sharia. This idea of revolution focuses first on dealing with the radicals’ own un-Islamic rulers (the “near enemy”)[9], before Muslims can direct jihad against external enemies (if leaders such as Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar as-Sadat are not true Muslims, they cannot lead jihad not even against a legitimate target, such as Israel). Significantly, radical Islamists consider jihad mandatory for all Muslims, making it an individual rather than a communal duty.

The Neglected Duty, a pamphlet produced by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s assassins to explain and justify their action, is perhaps the purest expression of this Islamist perspective on jihad (its author, Muhammad ’Abd al-Salam Faraj, was executed along with the actual killers). It argues that jihad as armed action is the cornerstone and heart of Islam; the neglect of jihad has caused the depressed position of Islam in the world. The Neglected Duty defined some rulers of the Muslim world, such as Sadat, as apostates, despite their profession of Islam and obedience to some of its laws, and advocated their execution. The Neglected Duty is messianic, asserting that Muslims must “exert every conceivable effort” to bring about the establishment of a truly Islamic government, a restoration of the caliphate, and the expansion of Dar al-Islam; and their success is inevitable.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s founder, Hassan al-Banna, stressed that “it is the nature of Islam to dominate, not to be dominated, to impose its law on all nations and to extend its power to the entire planet”, and included the jihad in the Brotherhood slogan “Allah is our purpose, the Prophet our leader, the Koran our constitution, jihad our way and dying for God our supreme objective”. The Jihad is also mentioned in the 2004 fatwa issued by Sheikh Yousef Al-Qaradawi, making it a religious obligation of Muslims to abduct and kill U.S. citizens in Iraq. It also advocated a war of Arabism and Islamic Jihad against the British and the Jews.

The Shi’a “Islamic Revolution”

A similar perspective is to be found in the modern Shi’a “Islamic revolution” doctrine. Ayatollah Khomeini (1903-89) contends that jurists, “by means of jihad and enjoining the good and forbidding the evil, must expose and overthrow tyrannical rulers and rouse the people so the universal movement of all alert Muslims can establish Islamic government in the place of tyrannical regimes”. The proper teaching of Islam will cause “the entire population to become mujahids”. Ayatollah Muhammad Mutahhari, a top ideologue of the Iranian Revolution, considers jihad a necessary consequence of Islam’s content; having political aims, Islam must sanction armed force and provide laws for its use. Mutahhari deems jihad defensive; but his definition includes the defense against oppression and this may require what international law would consider a war of aggression. Mutahhari finds that the doctrine of jihad marks Islam’s superiority over Christianity, for Christianity lacks the political and social agenda necessary for a doctrine of jihad.

The Taliban

Jihadi organizations inspired by the Taliban in Afghanistan are increasingly using verses from the Koran and early Islamic traditions to advance the cause of jihad and influence Muslim youth. In an editorial published in July 2013, Daily Outlook Afghanistan, a Kabul-based newspaper, warned that the Taliban are using Koranic verses to influence and prepare child suicide bombers. It mentioned that children are given amulets containing verses from the Koran by Taliban commanders, who tell them they will be protected from the explosion.

In April 2014, Haji Omar Khattab, the emir of the Afghan “Islami Tehreek Fidayee Mahaz (the Martyrdom Front of Afghanistan’s Islamic Movement)”, urged his followers to wage jihad in the light of the Koran and Hadith (sayings and deeds of Prophet Muhammad), stressing that “those waging jihad for the supremacy of Kalmat-ul-Allah [the word of Allah] will be given paradise. Entering paradise is a big success which can only be achieved through jihad. A Muslim who wages jihad is bestowed with two titles – hero or martyr. Both positions are esteemed”.

Almost all jihadi videos quote verses from the Koran to justify martyrdom missions. In July 2013, the Haqqani Network, a constituent of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, released a video which opens with Koranic verse 8:39: “And fight them ‘til there remains not any mischief, and the entire religion be only of Allah [on earth]; then if they desist, Allah is seeing their deeds”. Another video, released in May 2013 by Umar Media begins with the Koranic verse 9:14: “Fight against them. Allah will torment them at your hands and will humiliate them, and will help you against them, and will heal the breasts of the Muslims”.

In a cover story titled “The Boston Special – The Victorious Strangers”, the Azan Magazine published an article about the April 15, 2013 bombing of the Boston Marathon by quoting verses from the Koran which describe the futility of life in this world: “And this life of the world is only amusement and play! Verily, the home of the Hereafter, that is the life indeed, i.e. the eternal life that will never end… (Verse 29:64)”; “Think not of those who are killed in the way of Allah as dead. Nay, they are alive, with their Lord. (Verse 3:169)”. The author argued that the Tsarnaev brothers, who carried out the bombing, “realized they had been created to worship Allah alone (Verse 51:56); they realized that they have to return to Allah (Verse 67:2); they realized the ‘severe attack on the essence of Islam that the colonial powers of the day had engaged in’ (Verses 29:57-58); they realized that ‘success in Islam was not as the West defined, but that true success constituted meeting Allah’ (Verses 36:22, 18:14); they realized that ‘the Muslim ummah was one and the kuffar had divided the ummah both physically and mentally’ (Verses 85:11, 103:1-3).

The authors also cited a Koranic verse to provide legitimacy for martyrdom attacks: “And amongst mankind is he who sells himself, seeking the pleasure of Allah. And Allah is full of sympathy to (His) slaves” (Verse 2:207).

In the fasting month of Ramadan (July-August 2013), an official website of the Afghan Taliban published an interview with Mullah Abu Ahmad, Director of the Economic Commission of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the Taliban’s shadow government in the country, in which he argued that the Koran has ordered “Muslims to do jihad with their money”. In the interview he also cited several Koranic verses in support of his argument, including the Koran Verse 9:14: “Go forth, light or heavy, and strive with your wealth and your lives in the cause of Allah. That is best for you, if only you knew”. He added the Verse 2:261: “The similitude of those who spend their wealth in the way of Allah is like the similitude of a grain of corn which grows seven years; in each ear a hundred grains. And Allah multiplies it further for whomsoever He pleases and Allah is bountiful, all-knowing”.

Al-Qaeda

The radical-Islamic use of extreme violence was fuelled by a part of al-Qaeda’s ideology, which is based on the ideas of Abdallah Azzam (1941-1989), one of the founders of al-Qaeda. He contended that each Muslim individually has an obligation (Fard ayn) to wage an armed Jihad against the nonbelievers. According to Azzam, the armed Jihad is an individual commitment and no longer a collective commitment (fard kifaya), which releases the individual if there is a group that performs this task. Islam is threatened to such an extent that each Muslim individually (independently of a higher religious authority) is fully justified to engage in armed Jihad. Radical-Islamic networks are also characterized by a further radicalization of ideological thinking about Takfir (“branding as heretics”). In particular the ideas of Shukri Mustafa (1942-1978), the founder of Takfir wal Hijra movement have contributed to this further radicalization. According to this movement, in effect all those who adhere to another faith (both non-Muslims and Muslims who, according to the Takfiri, do not adhere to the proper form of Islam) are nonbelievers who are to be combated. Shukri Mustafa’s view of Takfir is a further radicalization of the views of Sayyid Qutb, who argued that regimes in Muslim countries that do not observe the “laws of the Islam” are to be considered as renegades to be fought with arms. The fight against the “renegade” regimes also entails a fight against non-Islamic powers that support and finance them.

2. The ISIS and its “Caliphate”: a breakthrough in Jihad

The most important trend within the global jihadi movement after the Arab uprisings in 2011 is its ability to step beyond just the terrorism box to add tools to its repertoire to expand its support from its clandestine base.

The war in Syria has become a new focal point for jihadists. The religious and ideological context of this conflict is important for several reasons: Syria (al Sham) is deemed to be the birthplace of the new Caliphate, and jihadists believe they can actually help to build the ideal Islamic state under Sharia law. Also, the old divide between Sunni and Shi’a Muslims has come to the surface in this conflict. The framing of this division as a necessary and violent struggle is an important element in the currently used ideology. Next to the conflict in Syria, however, other jihadist target areas may emerge in the Middle East and North Africa region, and it already happened in Iraq.

The ISIS declaration of the “Caliphate” on 29 June is considered the most significant development in international jihadism since 9/11. It was launched after a year (2013) during which ISIS carried out approximately 10,000 operations in Iraq, established control over significant parts of Syria; and got expelled from al-Qaeda for effectively challenging the continued legitimacy of its cause. Today, ISIS presents itself as the world’s new jihadist vanguard. Its spectacular military progress, unrivalled wealth, and slick media apparatus has seen it succeed in assuming the pre-eminence it has long sought.

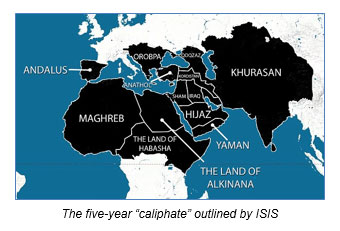

Another new feature that marks the ISIS jihad is the five-year plan to expand their boundaries beyond Muslim-majority countries.

Another new feature that marks the ISIS jihad is the five-year plan to expand their boundaries beyond Muslim-majority countries.

As well as plans to expand the caliphate throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and large parts of western Asia, the ISIS map also marks out an expansion in parts of Europe. Spain, which was ruled by Muslims for 700 years until 1492, is marked out as a territory the caliphate plans to have under its control by 2020. Elsewhere, ISIS plans to take control of the Balkan states, including Greece, Romania and Bulgaria, extending its territories in Eastern Europe as far as Austria.

ISIS regularly makes statements and releases propaganda calling for the return of the geographical boundaries in place before World War 1. The group insists that the carving up of the Ottoman Empire by Allied forces after the conflict (commonly known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement) was a deliberate attempt to divide Muslims and restrict the likelihood of another caliphate being established.

ISIS announced its regional aim in a series of photos posted on the Internet and called The Destruction of Sykes-Picot. From the point of view of the ISIS jihadists, the 1916 borders drawn in secret by British and French imperialists represented by Sir Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot to divide up Mesopotamia are not only irrelevant, they are destructible.

The Islamic State’s announcement is the first serious attempt at re-establishing the caliphate since the institution was abolished in 1924 by the Turkish republic, which replaced the Ottoman Empire after World War I. Over the past 90 years, there have been a few attempts to revive the caliphate, but none were particularly successful. Notable examples include Hizb ut-Tahrir, which rejects democracy and nationalism, and more recently, al-Qaeda.

The Islamic State’s announcement is also seen as a major challenge for al-Qaeda and its long-time position of leadership of the international jihadist cause. Counterterrorism analysts point out that the younger generation of the jihadist community is becoming more and more supportive of ISIS, largely out of fealty to its slick and proven capacity for attaining rapid results through brutality.

The history of ISIS

Jihadism grew rapidly in Iraq following the 2003 U.S. invasion of the country. In 2004, one of the largest jihadist groups, “Jamaat al-Tawhid and Jihad”, led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, became an al-Qaeda franchise group and renamed itself “al-Qaeda in the Land of the Two Rivers”. It was also commonly called “al-Qaeda in Iraq”. In 2006, the group formed the nucleus of a coalition of jihadist groups called the “Islamic State of Iraq”. It remained an al-Qaeda franchise and was placed under an Iraqi leader.

The Anbar Awakening in 2006-2007, coupled with the 2007 surge of U.S. troops in Iraq, severely damaged the organization, as did the U.S. operation that resulted in the deaths of the group’s top two leaders in April 2010. However, following the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq, the group was able to recover, becoming one of the largest jihadist groups in the world.

The civil war in Syria has proved to be a boon for the group. Initially, it provided support to Syrian jihadist groups, but eventually it became directly involved in the fighting and the strongest single jihadist group operating in Syria. Its operations in Syria have caused it to change its name to the “Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant”, also known as ISIL or ISIS. It has attempted to subsume other Syrian jihadist groups, including the Syrian al-Qaeda franchise group Jabhat al-Nusra. This led to a dispute that resulted in the group breaking from al-Qaeda and fighting against Jabhat al-Nusra.

An enigmatic “caliph”

The ISIS leader and self-appointed “Caliph” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is a relatively unknown and enigmatic figure, since much of what is known of him comes from al-Baghdadi himself, while other information is so disputed that it’s nearly impossible to discern fact from myth.

He is seen as a shrewd strategist, a prolific fundraiser and a ruthless killer, who in only one year may have surpassed even al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in international clout and prestige among Islamic militants. According to a senior U.S. intelligence official, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi may be considered the “true heir” to Osama bin Laden.

Born a Sunni in 1971 in Samarra, with the name Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai, he claims to be direct descendant of the prophet Muhammad. According to a biography released by jihadis, “he is a man from a religious family. His brothers and uncles include preachers and professors of Arabic language, rhetoric and logic”.

In July 2013, the Bahraini ideologue Turki al-Binali, writing under the pen name Abu Humam Bakr bin Abd al-Aziz al-Athari, wrote a biography of Baghdadi. In part it was to highlight Baghdadi’s family history which claims that he was a descendant of Prophet Muhammad – one of the key qualifications in Islamic history for becoming the caliph (historically, leader of all Muslims). It highlighted that Baghdadi came from the al-Bu Badri tribe, which is primarily based in Samarra and Diyala, north and east of Baghdad respectively, and known historically for being descendants of Muhammad.

The biography also mentions that he obtained a doctorate at the Islamic University in Baghdad, and some of his aliases include the title “Dr.” However, Baghdadi does not have credentials from esteemed Sunni religious establishments such as al-Azhar University in Cairo or the Islamic University of Medina in Saudi Arabia.

He is believed to have been an Islamic preacher in eastern Iraq at the time of the 2003 U.S. invasion. At that time, al-Baghdadi, along with some associates, created Jamaat Jaysh Ahl al-Sunnah wa-l-Jamaah (JJASJ) – the Army of the Sunni People Group – which operated in Samarra, Diyala, and Baghdad. Within the group, Baghdadi was the head of the Sharia committee. The US-led coalition forces detained him in 2004, but they supposedly released him since he was not viewed as a high-level threat.

The details of Baghdadi’s time in prison are contradictory. Some reports note that he was held as a “civilian internee” at the prison for 10 months in 2004. Other reports mention that he was captured by US forces in 2005 and spent four years at the Camp Bucca prison. The reason why he was apprehended is not publicly known; he could have been arrested on a specific charge or as part of a large sweep of insurgents or insurgent supporters. In any case, security officers familiar with the prison say Baghdadi’s stay contributed to his radicalization.

Following “al-Qaeda in the Land of Two Rivers” changing its name to Majlis Shura al-Mujahidin (Mujahideen Shura Council) in early 2006, JJASJ’s leadership pledged baya (oath of allegiance) to it and joined the umbrella organization. Within the new structure, Baghdadi joined the Sharia committees. Soon after the organization announced another change to its name in late 2006, to the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), he became the general supervisor of the Sharia committees, as well as a member of ISI’s senior consultative council. When ISI’s leader Abu Umar al-Baghdadi died in April 2010, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi succeeded him.

The group resurged with the civil war in Syria and conquered an area soon to become known as the “Islamic State of Iraq and Syria” (ISIS).

Following his appointment as head of the caliphate, ISIS demanded al-Baghdadi be referred to as Caliph Ibrahim, using the name given to the son of the Prophet Muhammad in order to strengthen the claim that he is now the leader of the Muslims and a direct successor to the prophet himself.

Al-Baghdadi has long been at odds with al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, and the two had a very public falling out after al-Baghdadi ignored al-Zawahiri’s demands that the Islamic State leave Syria. Fed up with al-Baghdadi and unable to control him, al-Zawahiri formally disavowed ISIS in February 2014.

The U.S. has a $10 million bounty on al-Baghdadi’s head.

New features of the ISIS jihad

Analysts point out that ISIS’ success in expanding and controlling a large territory that it tries to transform into a state structure is based on a clever use of the regional and international factors it its favor, as well as on ISIS taking hold of large financial resources, including those coming from the oil trade.

Efficient propaganda for international support

A worrying aspect derives from the transnational posture of ISIS, which, after creating in April 2013, a rift in the global jihadi movement when splitting with al-Qaeda and Jabhat al-Nusra, is now enjoying increasing shows of solidarity from the Middle East and from across the Muslim world, as well as from Western countries.

Several factors contribute to its popularity: the group’s jihad against the U.S. in Iraq (prior to its expansion into Syria); ISIS’ struggle against Iraq’s Shi’a government and its war against the Alawi Assad regime, which is an ally of the Shiites. ISIS’s activity on these fronts has helped bolster its image as the spearhead in the war against the enemies of Islam within and without the Muslim world, and raised its stature among supporters of global jihad.

Further adding to its popularity are ISIS’ achievements in Iraq and Syria, and its image as the only organization that is actualizing authentic Islamic ideals and striving towards establishing the Islamic idea of a greater caliphate. The persecution of ISIS, even by al-Qaeda, adds to its status in many circles as an “underdog” fighting for the goals of Islam and the good of all Muslims. Additionally, ISIS’ highly efficient propaganda apparatus circulates videos and publications via jihadi forums and social media, praising itself and criticizing its rivals and opponents.

The Muslims from the West who are leaving their home countries to join ISIS also add to the organization’s prestige, both inside and outside the Muslim world. These volunteers, who are widely covered by the media in their own countries, are themselves active users of social media, communicating with friends, followers and family back home and engaging in their own efforts to promote and recruit for the organization in the West. Further evidence of its sweeping popularity was the June 19, 2014 “One Billion Muslims Support ISIS” campaign, which urged ISIS sympathizers worldwide to express their support for the organization on Friday, June 20, and even devised a special Twitter hashtag for the purpose. The campaign elicited considerable response from supporters in numerous participants, who posted images and videos expressing their support for ISIS. The expressions of solidarity with ISIS on social and other media used common ISIS symbolism: posters of support, the use of the slogan baqiya wa-tatmaddad, “will remain and spread”, the black tawhid flag, widely used by other global jihad elements; and ISIS nasheeds, or Islamic songs. Other expressions of solidarity included photos of ISIS posters next to Western landmarks such as the Eiffel Tower in Paris, Big Ben in London, the Atomium building in Brussels, and the Coliseum in Rome; photos of ISIS posters alongside Western passports; and other images shared on social media.

Jihad with “international blessing”

Too violent for mainstream Syria’s rebels, too extreme for al-Qaeda, ISIS has many “parents”. At the start of the war in Syria, Turkey let foreign fighters cross its borders freely. Bashar al-Assad cynically helped ISIS gain an edge over the rest of the Syrian rebels by releasing extremists from his jails and selectively sparing it from attacks.

Another ISIS favoring factor was the Maliki government in Iraq, which was clearly representing only the Shi’a majority. The Iraqi army was purged of the independent-minded officers and, just after the last American troops left Iraq, in 2011, Maliki ordered the arrest of the Sunni vice-president (who promptly fled). Maliki also failed to maintain links with the Sunni clans who drove out al-Qaeda and ISIS’s forerunner in 2006.

Also, the Obama Administration is seen as having helped ISIS “by omission”. In quitting Iraq, the U.S. failed to win an agreement that left some American troops behind, or that provided American aerial support. The U.S. also refused Iraq’s calls for American airstrikes against the jihadists.

Access to oil and water

Some of the first sources of the ISIS’s funding remain unclear. Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki’s office issued a statement on 17 June 2014, accusing Saudi Arabia of giving ISIS “financial and moral support”. State funding by Saudi Arabia is complicated to prove but private giving is not. There are many private donations coming out of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states.

However, in the meantime, ISIS secured its own sources of funding from controlling gas and oil fields in the east of Syria and, after having overrun Mosul and other Iraqi cities, it acquired a lot of cash and gold bullion and military hardware.

The money it can earn from illicit oil sales further bolsters the group’s status as one of the richest self-funded terrorist outfits in the world, dependent for financial support not on foreign governments but on the money it has reaped from kidnappings and bank robberies. The group has also managed to steal expensive weaponry that the United States had left for the Iraqi military, freeing it from the need to spend its own money to buy such armaments.

Currently ISIS has access to both oil and water. In Syria its forces control the oil-producing region around Deir az-Zour, including Syria’s largest oilfield at al-Omar, reportedly even selling oil to their enemies, the Assad regime itself. They also control Syria’s largest dam, the Tabqa Dam at Lake Assad. In Iraq, ISIS controls the Falluja dam and has some access to Iraq’s largest oil refinery at Baiji.

Oil is quickly becoming an important financial asset for ISIS, which reportedly sells oil and liquid gas products extracted from fields under its control in Syria to Iraqi businessmen. In July, trucks with Iraqi number plates have been seen daily in the area of the Deir az-Zour oil fields, to fill up and transport oil toward western Iraq. Each barrel of oil is sold to Iraqi businessmen for $20 to $40[10]. Reportedly, the ISIS was also selling oil to Syrians living in areas under their control for $12 to $18, to draw the support of the local population.

The Islamic State seemingly controls the majority of Syria’s oilfields, especially in the country’s east; human rights observers say 60 percent of Syrian oil fields are in the hands of militants or tribes. The Islamic State also seems to have control of several small oil fields in Iraq as well, though reports differ on whether most of those wells are capped or whether the Islamists are producing and shipping serious volumes of stolen Iraqi oil across the border.

In all, energy experts estimate that illicit production in Iraq and Syria is about 80,000 barrels a day. That’s a tiny amount compared with stable oil-producing countries’ output, but it is a lot of potentially valuable oil in the hands of a non-state group. The developments made the U.N., on 28 July, warn countries against buying oil from militants in Iraq or Syria, saying that such purchases would violate U.N. sanctions on the terrorist group.

Economic analysts assess that for ISIS, the war has the potential of turning into an extremely lucrative, and highly dangerous, endeavor with a very high margin of return, given the initial investment. If they succeed in their goals, the result would be what is already called “high-octane terrorism”, and it is only a matter of time before the battle waged by the Islamic State moves into Phase Two. The group will benefit not only from the huge amount of money stolen from banks in cities they conquered, but also from billions of dollars more from the oil they are about to sell. This will give them a continuous source of serious income that will make them a most potent and dangerous group of armed fighters.

A caliphate to govern

Notwithstanding the success of its “blitzkrieg jihad”, analysts point out that ISIS is already facing difficulties in governing the territory they called their “caliphate”, a process that depends on many factors – local tribal support, economic viability, access to fuel and water, perceptions of their religious authority and that of their leader and self-appointed caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and whether or not ISIS overreach themselves.

So far, ISIS has enjoyed a short-term military success, largely through a combination of fear and firepower, with an original “psyops” campaign aiming to terrify their opponents by flooding social media on the internet with gruesome images and videos of what happens to their enemies. However, ISIS had only about 10,000-15,000 fighters at most when it began taking over much of western Iraq in June, and it was reported that they took over Mosul with no more than 800 fighters.

ISIS’ chances to govern are heavily dependent on the support of local tribes and militias, without whom they could not hope to hold down a city of two million like Mosul. So far, ISIS’ ability to control lands has been based on deals with local militants willing to do the “ruling” for them. Some of these deals are based on fear, others on a temporary meeting of interests, at times it is as crude as financial deals being struck between different gangs. Maintaining power, order and loyalty in the longer term will mean ISIS must be able to keep those interests onside.

Even the millions that the Islamic State seems to be raking in by trucking stolen oil across porous borders are not enough to meet the obligations created by the group’s own headlong expansion. Taking over big chunks of territory, as in eastern Syria and in northern Iraq, could also leave it forced to take on the sorts of expensive obligations, such as paying salaries, collecting the trash, and keeping the lights on, usually reserved for governments.

Money is also desperately needed to cover the salaries of public workers in places the militants occupy, especially after the government in Baghdad froze public salaries for those areas. That came as a double blow to the group, which has no local incomes to extort, and moreover, has to pay the payroll tab itself.

However, other reports mentioned, for the ISIS controlled territory, an efficient municipal garbage collection, safer streets, generous distribution of fuel and food to the poor, which evoked for analysts the beginning of the Taliban in Afghanistan in 1994, gradually increasing their territory until the 9/11 attacks on the US provoked the campaign that drove them from power in 2001.

Recently, ISIS organized a hop-on hop-off bus service over their “caliphate”, with twice-weekly tours from Syria’s Raqqa to Iraq’s Anbar. The buses fly the group’s black flag and play jihadist songs throughout the journey. The passengers can take the bus anywhere they want and no passport is needed to cross the former border. The bus is accompanied by an interpreter and escorted by armed vehicles.

According to the local population, the new service is very popular, and the only difference between it and any other bus company is that “it treats areas under ISIS control in Iraq and Syria as one state”.

The bus is also to be used for “honeymoon tours”, for people who will use the services of a recently opened “marriage bureau”, for women who want to wed the group’s fighters. The office is operating from al-Bab, a town in Aleppo province of northern Syria, and the interested parties were being asked to provide their names and addresses, “and ISIS fighters will come knocking at their door and officially ask for marriage”.

“Planting the seeds of its destruction”

In spite of such apparently “favorable” local developments, ISIS’ barbarity, lack of outreach to even like-minded Salafi groups, and territorial overreach may have already sown the seeds of its own downfall.

ISIS seems not to be learning from the lesson of their predecessors of al-Qaeda who temporarily ruled much of the Anbar province in Iraq in 2006. Under the brutal leadership of Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, the jihadists managed to alienate most of the local population, persecuting the Muslim population in spite of the requests of the al-Qaeda leadership in Pakistan. In the end, Jordanian intelligence tracked down al-Zarqawi, who died in a U.S. airstrike, and the jihadists were driven out by the local tribes backed by U.S. troops. The similar brutal and sadistic manner in which ISIS rules the conquered territory made al-Qaeda condemn ISIS’ excesses and in February 2014 they formally disowned the whole organization.

Rejected by the scholars

The violence and brutality of ISIS also made several Muslim scholars to deny its Sunni religion, pointing out that much of ISIS’ behavior is un-Islamic, since they committed atrocities forbidden by the Muslim religion, including the killing of dozens of Sunni imams who refused to swear allegiance.