Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s alliance with his nationalist partner appears under growing strain amid a combination of domestic and external pressures.

Three politically motivated assaults on figures critical of the government’s nationalist ally rattled the Turkish capital last week. The brazen violence sent shockwaves across opposition quarters, but President Recep Tayyip Erdogan also seems to have gotten food for thought.

The victims were Selcuk Ozdag, deputy chair of the opposition Future Party, Orhan Uguroglu, a journalist heading the Ankara office of the daily Yenicag, and Afsin Hatipoglu, a lawyer who hosts a TV program on a channel critical of the government, all battered in broad daylight outside their homes by masked men wielding sticks and guns.

What did the victims have in common? All had vocally criticized the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), the election ally and de facto government partner of Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), days before the attacks. More importantly, they all come from nationalist political background, but have become critics of the MHP, the backbone of Turkey’s nationalist movement, over its alliance with the AKP. Hatipoglu, for instance, is a former head of the ultra-nationalist Idealist Hearths, known also as the Grey Wolves. The rift within the MHP has already spawned a splinter party that has aligned with the main opposition. AKP defectors, too, have formed new parties, including the Future Party, led by former Premier Ahmet Davutoglu.

Ozdag suffered the worst injuries, including broken fingers and 17 stitches on his head. The findings of the police investigation suggest the attack was well planned. The five assailants reportedly conducted reconnaissance around Ozdag’s home for a week. The police have arrested two of the suspects thus far. They are both young men actively involved in the Ankara branch of the Idealist Hearths. The group, notorious for deadly street clashes with left-wingers in the 1970s, functions as the youth branch of the MHP.

A number of similar attacks on media figures of nationalist background have taken place in the past two years in what increasingly looks like a systematic effort of intimidation. The MHP links of the assailants suggest instigation by the party’s policies at the very least. MHP leader Devlet Bahceli has only compounded the misgivings by failing to condemn the latest attacks.

Obviously, the assaults aim to bully opposition politicians and media figures, especially those critical of the MHP. But they appear to carry a message to Erdogan as well — a reminder that his nationalist allies will not shy away from stirring political tensions to force him toe the line.

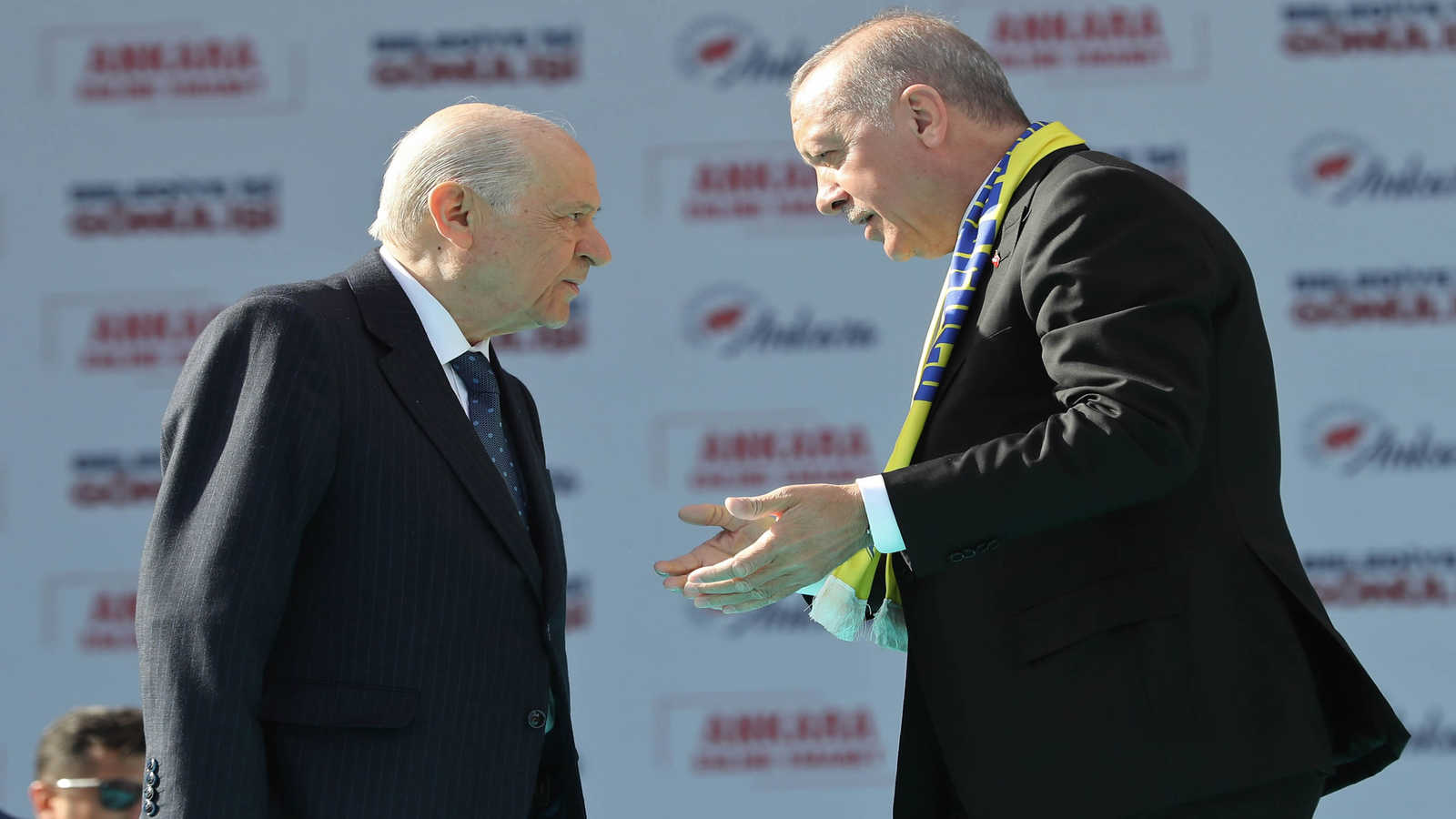

Indeed, the AKP’s alliance with the MHP, which helped Erdogan install the executive presidency system and win the elections in 2018, is under increasing strain from both domestic dynamics and foreign policy factors. Bahceli wants to make sure that Erdogan, a pragmatist with a copious record of U-turns, would not drop the MHP in favor of more convenient allies ahead of elections in 2023.

Erdogan and Bahceli have both asserted that their alliance is intact and bound to win the 2023 elections, even though opinion polls show their popular support is on the decline.

Still, a series of developments in the past several months offer ample clues that the AKP-MHP relationship is not as smooth as it used to be in the presidential elections in 2018 or the municipal polls the following year.

In domestic politics, Erdogan and Bahceli are at odds on several crucial issues. The first is Erdogan’s promise of judicial and economic reforms, which he is likely to unveil in February. The judicial package is expected to seek some degree of normalization in the domestic scene, where an unprecedented crackdown on dissent has landed thousands in jail, including Turkey’s most popular Kurdish politician, Selahattin Demirtas. Bahceli is averse to such relaxation on grounds that the security of the state is at stake.

Second, Erdogan has been visiting small parties of various stripes in an apparent bid to shape a third political bloc that would be under his control and fracture the opposition. But such a bloc could also ease Erdogan’s dependence on the MHP; hence, his contacts with other parties have fueled a confidence crisis in the alliance.

Standing out among Erdogan’s contacts are those with the Felicity Party, the successor of the Islamist Welfare Party in which Erdogan’s political career began. Tellingly, Erdogan this week visited the grave of Necmettin Erbakan, the Welfare leader and his political mentor until the two became estranged after a split in the movement.

The tremors in the AKP-MHP alliance are ideological as well, stemming from rivalry on how to mold the new Turkish nationalism. Will it give precedence to Islamic tenets or secular values?

Erdogan is well aware that MHP-inspired nationalism is on the rise in AKP grassroots, threatening to secularize and snatch some segments of his base. To prevent such shifts, he needs to make sure that his base remains committed to conservative values and keep his own political Islamist credentials alive.

Another reason for the AKP-MHP confidence crisis has to do with a plan to amend electoral laws. The two allies are quietly working on a blueprint, but have yet to reach a consensus. While the AKP hopes for changes that will facilitate Erdogan’s reelection, the MHP insists on maintaining the 50% threshold that a presidential candidate needs to pass to win. The MHP is averse also to any concessions that could pave the way for a return to the parliamentary system. In the MHP’s view, only a powerful government, drawing on the executive presidency system and the AKP-MHP alliance, could deal with perceived existential threats to Turkey from a hostile neighborhood and political instability and terrorist groups at home.

A further point of contention concerns the Kurdish-dominated Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), the third-largest force in parliament. The MHP has called for outlawing the HDP for allegedly collaborating with terrorists and inciting violence. Erdogan appears reluctant on such a move, wary of antagonizing his own Kurdish supporters and sparking fresh tensions in already crisis-laden ties with the European Union and the United States.

Ankara’s recent efforts to moderate its foreign policy are not to the MHP’s liking, either. These include efforts to mend fences with the EU, the planned resumption of talks with Greece and overtures to the new US administration, which is expected to be tougher on Turkey with policies that could put further strain on the AKP-MHP alliance.

In sum, Erdogan’s need to recalibrate his foreign policy and woo new allies at home marks a new chapter for the AKP-MHP alliance, in which the MHP seems to have even greater leverage to exert pressure on Erdogan.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News