In early December 2020, at least eight people were killed and hundreds of others were injured during violent protests in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) sparked by deteriorating economic conditions and the government’s failure to pay public sector salaries. Seven of the dead, including a 13-year-old boy, were killed when security forces opened fire on demonstrators. The offices of parties from across the political spectrum were torched in towns outside the major cities and in Sulaimaniya. The government arrested protest organizers and shut down a television station that was covering the demonstrations. Freedom of expression in the KRI was dealt another blow on Feb. 16, when a court in Erbil sentenced five independent journalists and activists to six years in prison on charges of “endangering the national security of the Kurdistan Region.” Critics argued that the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) used the trial and the harsh sentences as a way to silence dissent and that the evidence presented was obtained through coercion.

Stories like these rarely break out beyond the local press, and analysis about the KRI is all too often driven by elite-centered narratives that do not properly account for the opinions and social realities of the broader population. This does a disservice not only to the ostensible subjects of reporting and analysis about the Kurdistan Region but also reinforces misperceptions about Kurdistan that have major policy implications.

This article will examine the social and political dynamics that currently shape the Kurdistan Region, explore the problem of elite-centered reportage, seek to explain why counternarratives are generally obscured, and propose a refocusing of reporting and analysis in a way that takes public opinion and social realities seriously.

To do so, we spoke with several experienced Kurdish journalists and analysts, including Kamal Chomani, Shivan Fazil, and Niaz Najmaddin, to get their perspectives on reporting about the KRI and what they see as the difficulties in discerning public opinion and parsing it from the elite-driven narratives that comprise most coverage. We also interviewed Shirin Kawa Garmiyani, a member of Kurdistan’s Parliament who joined the December protests, to provide insight into the dynamics she sees from her home in the rural areas outside the region’s major cities. Finally, we critically examine public opinion surveys that include data about the Kurdistan Region, specifically those published in the Arab Barometer, the World Values Survey, and by the National Democratic Institute (NDI).

In doing so, we argue that examining the societal level of politics not only helps strengthen analysis about the Kurdistan Region but is also of paramount importance for contesting and subverting the elite narratives that hamper understanding of important political realities in the KRI.

What really shapes KRI’s society

Often marketed in positive terms as “the other Iraq,” the KRI is in reality beset by acute structural problems that are often papered over by government officials, journalists, and academics, or viewed relativistically with regard to problematic dynamics in Baghdad and other parts of the Middle East. Full of promise as a parliamentary democracy after achieving de facto autonomy from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in 1991, the KRI has since regressed into a political duopoly dominated by family-centered parties, particularly the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). These two parties control state institutions at all levels, the military, and the internal security forces, and work to prevent authentic democratic discourse by restricting free access to government information, arresting critical journalists and political activists, and funding affiliated media enterprises. Moreover, they oversee a pervasive patronage system fueled by the region’s oil industry and budget transfers from the Iraqi government that gives public sector jobs to those perceived as politically loyal and allocates contracts to party-affiliated businesses.

Since 2014, however, the region’s economy has hit rocky shoals, and the bonds of the social compact, which tolerated the erosion of democratic norms in return for economic growth and political stability, have frayed. In response to budget disputes with Baghdad that reduced cash transfers to Erbil and lower oil prices, the KRG instituted a range of austerity policies starting in 2015, including a years-long public sector hiring freeze and the withholding or delaying of significant portions of public sector workers’ monthly salaries. Meanwhile, independent entrepreneurship continues to be hampered by the lack of a modern financial and banking system and byzantine registration and operating procedures. All of this combines to make it difficult for young people to enter the workforce, especially those who lack connections to the KDP or PUK. In a demographically young country like Iraq, this is a recipe for trouble. This dysfunctional system, riven with inequality and stratification and without the means of effective political recourse, has bred simmering dissatisfaction with the ruling elite, which occasionally reaches a boiling point, as it did during the violent protests across Sulaimaniya and Halabja between Dec. 2 and 11.

The demonstrations were the most significant in more than two years and drew comparisons with large-scale anti-corruption protests in the KRI in 2011. If they covered the demonstrations at all, most foreign outlets framed the protests in terms of the unpaid salaries of middle-class government employees, the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, and low global oil prices, largely ignoring the complete political and economic disillusionment of the unemployed youth who were actually the ones in the streets.

An MP in the Kurdistan Parliament representing the Change Movement (Gorran), Shirin Kawa Garmiyani attended one of the early protests in Sulaimaniya on Dec. 3. In an interview, she told us that these protests were different from previous rounds, during which demonstrators had called for the resolution of specific issues or more general reform of the political system. “Now the mass of people protesting are genuinely hungry and the poor people do not ask for reform anymore. They want a revolution, a complete systemic change,” Garmiyani said. The protests and the response to them from the KRG and the ruling parties “have proven to the people that there is absolutely no possibility for them to participate, to change anything anymore. The last means of resistance, protests, are met with complete violence.”

This narrative, where the people of the Kurdistan Region and the youth in particular face a frozen and dysfunctional government, a stillborn private sector enmeshed in red tape, and a corrupt, rent-seeking elite who are all too willing to use violence to protect their privilege, rarely appears in the Western press or in think-tank briefs. Yet it is on full display to anyone who spends the time to even just scratch the surface of public opinion.

The shortcomings of current reporting on the KRI

Protests in the Kurdistan Region generally go under-reported in Western media in comparison with similar events, like the Arab Spring in 2011 or the anti-government protests in Baghdad and Iraq’s southern governorates in late 2019, despite obvious parallels and similar root causes. Part of that we attribute to the KRI’s smaller relative size and distance from metropoles like Cairo and Baghdad, but also to the complicated, multi-layered political dynamics in the KRI and greater Kurdistan that sublimate events there into the pre-existing narratives that seek to explain politics in the states where Kurds reside. Grasping for a hook to resonate with their home audiences, Western journalists and analysts who focus on the MENA region and analysts working for Western institutes and outlets often end up with narratives about events in the KRI that ignore the opinions and concerns of the local population and instead focus on broader geopolitical dynamics. Moreover, in the region’s restrictive information environment, explanations of events are often subject to partisan and elite influence games, which appear to have local authenticity but also fail to properly capture public opinion. These two dynamics play out through the problematic combination of the sectarian muhasasa framing of Iraqi politics and society, which essentializes “the Kurds” and their concerns as those of the ruling elite and their interests. Kamal Chomani, an independent journalist from KRI, argues that this essentialization comes out of a need to show that there had been some positive outcome from the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, which the relatively prosperous KRI may appear to provide.

A Foreign Policy article published in late November 2020 is a prime example of the result. The article itself starts off by criticizing approaches that treat Kurds as a monolithic entity with cohesive interests and views, before doing exactly that by asserting that Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) influence is the main problem facing the Kurdish people in the KRI and relying heavily on interviews with KDP officials like Sirwan Barzani to back that claim. For decades, the KDP leadership has taken a hard line against the PKK, but in reality, overall attitudes in the Kurdistan Region toward the PKK are quite varied. Emphasis of the apparent security threat posed by a group the KDP leadership views as a rival suits its own interests, but people in the KRI see economic issues as most important to them by a wide margin. More broadly, this also shows how far removed partisan, elite-driven narratives about geopolitics can be from the realities of public opinion in the KRI.

On a practical level, foreign reporters and analysts writing about the KRI are presented with an access puzzle: The elite are readily available, but the people often are not. Most outsiders require institutional and logistical support to obtain access not only to the KRI itself but to the content of their research and reporting, for example, the frontlines of the war against ISIS. Kurdish, in particular the Sorani and Badini varieties spoken in the KRI, does not enjoy widespread usage outside of Kurdistan. According to analyst Shivan Fazil, in recent years political elites, especially those from the KDP, became heavily invested in providing access for Westerners, who then often reflect their views.

The KRG also worked hard to promote the idea of the KRI as “the other Iraq,” essentially a branding strategy to market its image as a democratic and Western-oriented island in a Middle East that is descending into chaos (Glastonbury 2018). Such attempts at framing are also done in other ways as well, including in academic literature. Shortly after the first wave of internally displaced people fleeing ISIS reached the Kurdistan Region, former KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani requested that the World Bank conduct a study to provide empirical backing to his government’s claim that the financial crisis there was mainly the result of external problems (World Bank 2015). Although economic conditions in the KRI began deteriorating a year earlier, similar studies were never requested about the impact of corruption or youth unemployment on the region’s economy, which might have placed blame on the parties’ mismanagement. Although such studies can be done with the utmost academic rigor, the research questions will always be dependent on who can request such research.

This asymmetry of resources also influences what sources are seen as valid. Kamal Chomani tells us that many Western reporters simply repeat what Kurdish media says, which itself is highly censored through party ownership of outlets, and only seek out contacts from big-name institutions like the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani (AUIS) and University of Kurdistan Hawler (UKH), which have strong ties with the elite and the parties, rather than academics at lower-profile universities. Fazil tells us that many of the former are reluctant to offer critical analysis of the KRI for fear of burning bridges with the elite — a reticence that also affects analysts working at think tanks in the West. While the language barrier can be daunting, it is not insurmountable. As Chomani says, “You don’t necessarily need to speak [Kurdish], but you need to put in the effort to understand the people.”

Access is, however, not the only issue. One way of determining what matters to people in the KRI is by looking at survey data, which is indeed available. Some institutions regularly collect quantitative and qualitative data on the ground. They have great access and capable researchers working for them, but used different approaches when analyzing Iraq’s 2019 protests versus those in the Kurdistan Region’ in 2020, for example.

The Institute of Regional and International Studies (IRIS) at AUIS in Sulaimaniya, for instance, published an in-depth report citing the voices of protesters during the Iraq protests, clearly realizing that the voices of the actual population are of great importance to understand social dynamics. However, the same was not done for the Kurdistan protests, where yet again, the analysis was much more focused on top-down observations of problems and elite structures, instead of deriving insights from protesters’ opinions.

Another example is Chatham House, which published survey data on people’s perceptions of the Iraqi protests in 2020. It asked KRI citizens for their opinion, which was in many areas very favorable, again indicating that both sets of protests have similar socio-economic foundations. The same, however, was not done with respect to the repeated Kurdistan protests. Instead, just recently, another survey was published onIraqis’ attitudes toward the centralization or decentralization of services — a widely-discussed topic in the West and elite circles. The survey gave specific attention to KRI citizens’ take on centralization, assuming that it is a priority for most people in the Kurdistan Region, as other reports have previously suggested. While some say decentralization helps provide accountability and efficiency and redress historical grievances, others argue that centralization would ensure better services and streamline bureaucracy. Discussion gets heated quickly on what is ostensibly a dry topic because it is used by a variety of political factions to seek influence and power within Iraq’s constitutional arrangement. In this discourse, the KDP and PUK are looking to reinforce the walls of their bailiwick in the KRI, while Sunni and Shi’a groups in the west and south and parties in Baghdad work to undermine them. However, it does raise the question of whether the federalism debate through which the KRI is looked at in many cases is really what bothers people in their everyday lives, or if analysts are merely reproducing elite preferences in their policy papers.

The findings in the recent data supplied by the Arab Barometer (2019), the World Values Survey (Inglehart et al. 2020), and NDI in 2019 can be used to debunk presumptions common in the current discourse about the KRI that do not reflect the priorities of the population at large. The presented data shows that when it comes to the KRI’s population there is no reason to believe that they trust any institution at the regional or federal administrative levels to actually meet their needs. According to the survey conducted by NDI, only 30% of all respondents said the Iraqi government is “very or somewhat effective” and 39% of those in the KRI said the KRG is “very or somewhat effective.”

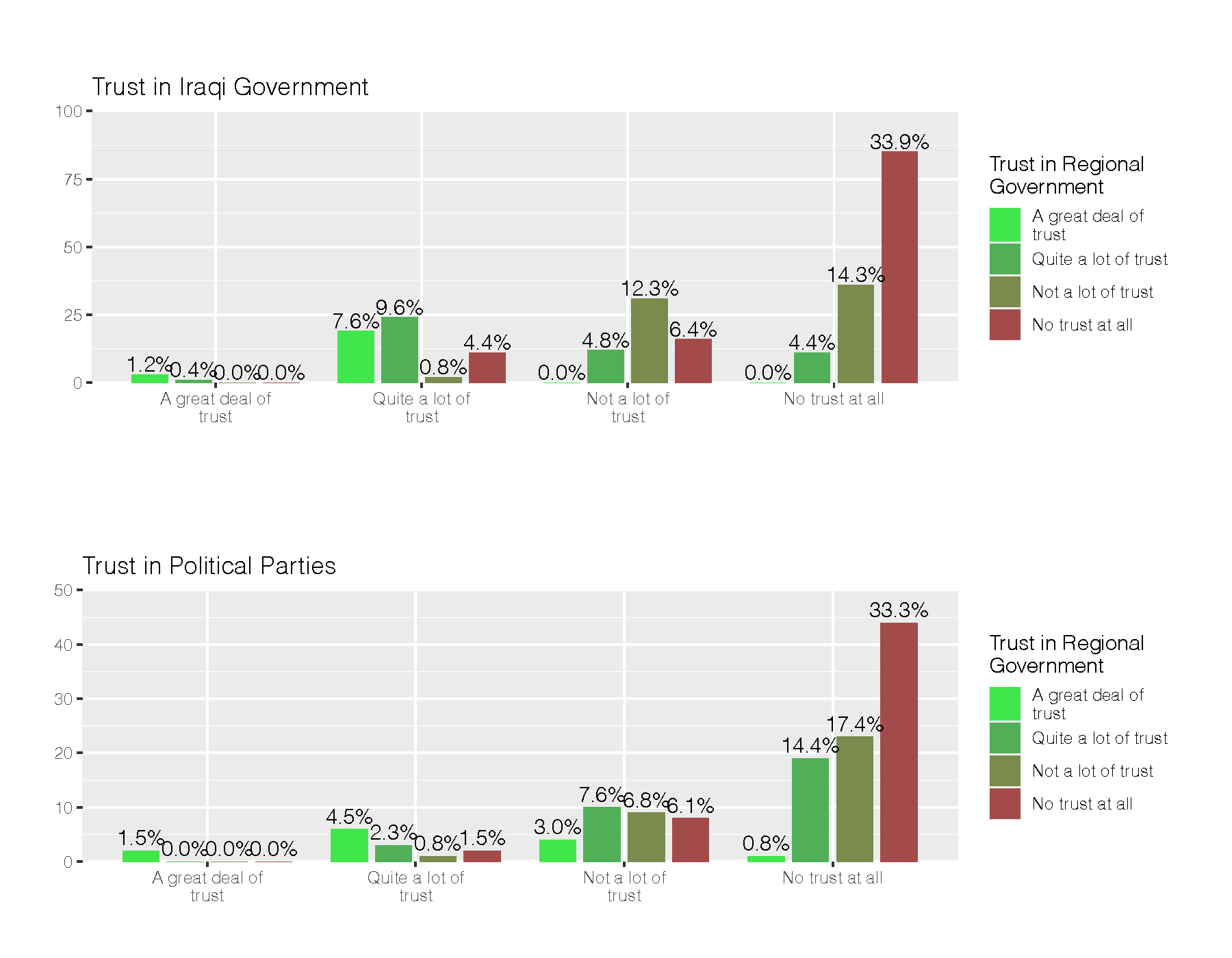

As the Arab Barometer data in Figure 1 shows, the majority of KRI respondents do not trust the central government, the regional government, or the political parties, suggesting that the fierce debates over decentralization and centralization are mostly a concern among political elites; when it comes to the population, it is evident that political institutions enjoy very low levels of trust. Therefore, beyond debating which responsibility could be shifted from one administrative level to another, one should urgently address the problem of how low levels of trust in the overall political system can be solved. While worthy of study and discussion, the attention the decentralization debate receives is out of proportion to the degree that it animates popular discussion. Further, as Anderson (2015) shows in great detail, it is quite problematic to look at Kurdish and non-Kurdish debates on federalism through the same lens. Kurdish autonomy is one of the great post-2003 consequences of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal rule and the fact that the concept of the “region” in the Iraqi constitution was expanded to not only Kurds, but other groups as well, was itself a political move (Anderson 2015, 86f). Therefore, indirectly presenting a choice between a corrupt autonomy versus a “better” centralized rule as the only policy option for Kurds in Iraq ignores this multi-layered reality.

Likewise, framing geopolitical issues, like those about the PKK, as a primary matter of concern in KRI citizens’ daily lives is not substantiated by the survey data. Evidently, 35% of KRI citizens perceive Turkey to be the greatest state-based threat to the country, compared to only 1% of non-KRI Iraqi citizens, which shows that Turkish interventionism is an issue that bothers Kurds in Iraq in particular (see: Jasim 2021, Arab Barometer 2019).

In its survey, NDI asked respondents, who were from all of Iraq’s governorates, to assess the day-to-day security threat posed by a variety of non-state actors, but did not include the PKK on the list. Survey designs like this pose a challenge to properly assessing the views of people in the Kurdistan Region about their feelings regarding non-state actors that are relevant in their home areas, like the PKK, and also show the Baghdad-centric approach that we argue prevents researchers and journalists from accessing empirically sound data about public opinion in the KRI.

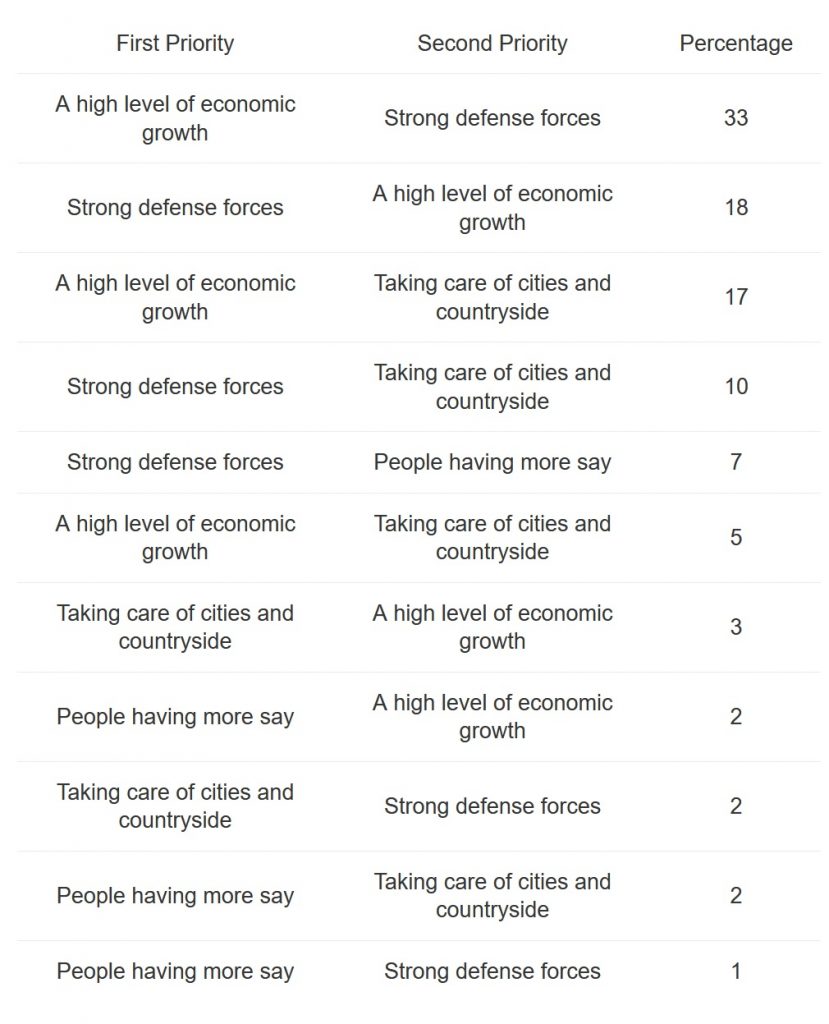

On top of that, looking at the latest World Values Survey data in Table 1, when asked about political topics that respondents think should be the priority for the government, many saw matters of military defense as secondary to economic growth, the most pressing concern. Foreign policy certainly matters, but for a population that has borne the brunt of years of mass unemployment and repeated public salary cuts, it is just one part of a larger picture. The 2019 NDI survey found that “lack of employment opportunities and corruption [were the] most important for the government to address,” with corruption, job opportunities, and the cost of living as the most important topics for Iraqis. This is especially true for the KRI’s young population, the driving force behind the December 2020 protests.

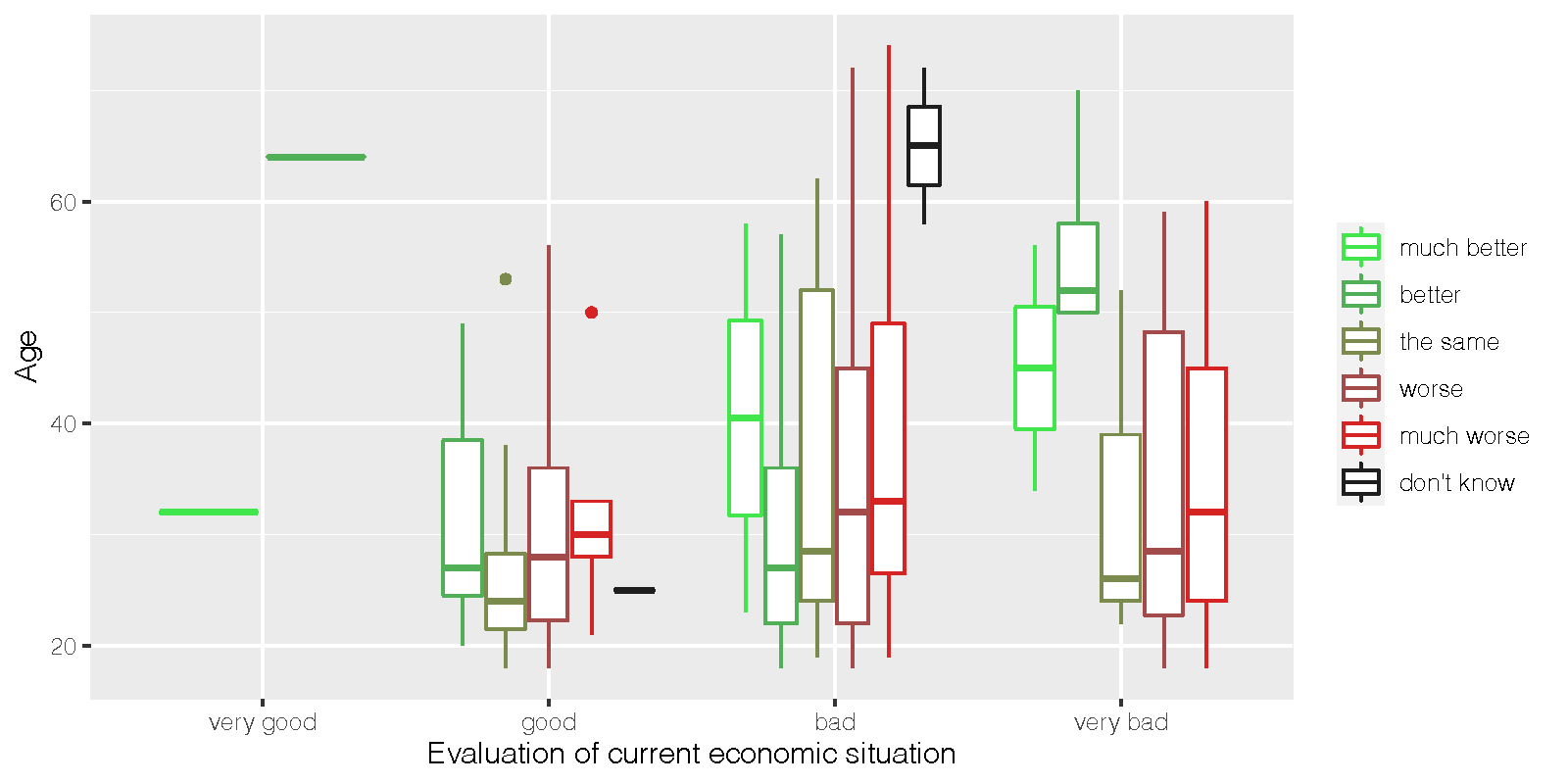

As Figure 2 shows, not only do many in the KRI evaluate the current economic situation as “bad” or “very bad,” but that attitude is especially prevalent for those around a mean age of 25 to 30, who say that the economic situation is at least as bad as it was five years ago, suggesting that it is the youth who feel the negative economic pressures most acutely. The concerns of frustrated and hopeless youth demanding systematic change that Shirin Kawa Garmiyani spoke about, therefore, show up empirically in the data. The public dissatisfaction that is reflected in low levels of political trust and concerns about the economy, corruption, and joblessness is a guarantee of future protests, which could even exceed the scope of those in the past, as Garmiyani warns. Reporting on the social groups that bear the brunt of the structural economic problems in the KRI and shining a light onto those structures is critical to understanding the source of protests and to be able to correctly analyze and give an account of “the people.”

What can be improved in Western analysis

In these examples, reporting and analysis of the Kurdistan Region fail to pay proper attention to the dynamics that drive the everyday concerns of the people: a dysfunctional economic system riven with inequality and stratification that breeds dissatisfaction with the ruling elite. The question is how can reporting be improved and what rules of thumb can be established to enhance methodology and practice in Western journalism and academia. Based on our interviewees’ insights and our own critique, we came up with the following recommendations:

- Having the same research standards for Kurdish and non-Kurdish citizens

As is evident in the pieces discussed, bottom-up narratives seem to be used for non-Kurdish parts of Iraq only. This should change, since we have reached a point in Iraqi Kurdish history where desire for autonomy and criticism of their own parties and elite structures yield an increasingly complex dynamic. Polling in the Kurdistan Region should be done much more frequently and researchers should be broadminded and focused on what questions are asked. Furthermore, these surveys should be conducted in Kurdish, rather than Arabic, which has hamstrung data collection in the KRI in the past. To be able to account for this population, therefore, survey instruments need to be adapted to a non-Baghdad-centered reality.

- Amplifying independent Kurdish voices

Most of the things that journalists and academics from the West want to talk about have been analyzed by local professionals before. Western observers have to accept that people from the region are indeed capable of analyzing their own situation and that there is previous work that can provide a solid foundation for their own analyses, provided it is properly acknowledged. Fazil also tells us that it is paramount to hire local Kurdish journalists. They often have in-depth insight into social dynamics, access to local sources, and knowledge of the greater discussion going on. Instead of only using locals only as fixers, translators, and drivers, Western professionals should regard their local counterparts as equals that provide unique access. It is also important to seek out sources beyond “the usual suspects,” who often have close ties with the elite and tend to reflect elite concerns.

- Not every field trip is needed: Use the diaspora.

Kamal Chomani tells us that one frequent problem with Western journalists reporting from the Kurdistan Region is the sensationalism and orientalism that underlies their stories. A catchy story from the field seems to be worth more than in-depth coverage of the nuances of social phenomena. When lacking the language skills and access to credible sources, an immediate trip to the field should not be the first thing to consider when preparing for a story. Niaz Najmaddin tells us that back in the 1990s, there was a wall between the people of Kurdistan and the West, but now there is a large Kurdish diaspora in many Western countries that can act as a vital bridge. Before starting premature and ill-prepared trips to the field, journalists and academics can meet with Kurds living in their own countries and have preparatory talks to first develop an idea of what is going to confront them when they get there, again keeping in mind that the elite/popular divide is also present in the Western diaspora.

- Knowing your privilege in order to use it for good

Unquestionably, the job of independent Kurdish journalists and intellectuals is a dangerous one because of the risk of arrest and violence from party-affiliated security forces. The KRG’s vindictive approach to journalists like those sentenced on Feb. 16 exemplifies the hostility of the government and the parties toward independent and critical voices. In court settings, the prosecution often makes a strategic decision to deny defendants’ status as journalists and therefore skirts the protections that the KRG’s Press Law provides. The trial also shows that the government is willing to make weak, circumstantial cases against local journalists for using material and communication and research techniques that would be completely normal in the West to punish those who write stories that cast the authorities in a poor light. Because of this, local journalists may work under a pseudonym and prepare for the worst. Western professionals and those working for Western institutions, however, are not targeted in the same way and have greater institutional and structural protections. On top of that, their voices are amplified much more than local ones, even in the Kurdistan Region itself.

Niaz Najmaddin cites an example: “During the referendum for independence, a Kurdish version of an interview with the Slovenian philosopher Slavoi Žižek was published where he supported an independent Kurdish state. His idea has been used by pro-referendum journalists, academics, and others while millions of ordinary people said ‘no’ to the referendum, and history has shown that they were correct.” Later on, Žižek changed his opinion. However, instead of criticizing the Kurdish political elite, in a subsequent interview with The Spectator he went on to call “the Kurds of Iraq” conservative compared to the Kurds of Syria, simplifying yet again. Najmaddin tells us that such sweeping statements on nuanced topics are dangerous, particularly coming from prominent figures. In a postcolonial setting like the KRI, therefore, we see the value placed on a well-known, White, Western voice. Western authors should be aware of this and be careful about making bold claims about the region.

When well-reflected, though, the privilege of Western voices can also be used for good. Fazil tells us that those who have the privilege of not having to be afraid of the security forces and censorship in the KRI can do more to help those who, for different material and legal reasons, do not have the access to the same resources and institutional support as Western reporters and analysts. Including Kurdish professionals into Western intellectual and journalistic networks can give them institutional backing that in turn makes them stronger vis-à-vis state repression.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News