Although the Shanghai Cooperation Organization is a regional organization that is generally externally focused in its declarations and statements, it is internally focused in its practices and actions.

Since its establishment in 2001, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) has experienced several horizontal (expansion of members) and vertical (tasks and functions) evolutions. The change of Iran’s membership from observer and non-voting status to a full member in September 2021 is only the latest important development to occur. Considered in parallel with rising political, military, and economic tensions between China and Russia, one the one hand, and the West, on the other, many are returning to the old hypothesis and argument that the SCO is an “Eastern Bloc” that is seeking confrontation with the West and will become a “New Warsaw Pact” or “Eastern NATO.” But there are five reasons—including the SCO’s nature and performance over the last two decades, as well as the policies and approaches of its members—why this hypothesis should be soundly rejected.

The first reason is that the SCO’s charter, which is explicitly mentioned in Article 2 (Principles) states that the “SCO being not directed against other States and international organizations.” Over the past two decades, however, the SCO has issued statements criticizing the United States and NATO in various areas, including for unilateral actions taken internationally; the military intervention in Afghanistan; and the use of human rights, democracy, and freedom of expression to interfere in the internal affairs of SCO member states. However, in practice, the SCO has remained faithful to Article 2 of its charter.

Some experts point to the SCO’s opposition to the establishment of U.S. military bases in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan after September 11, 2001, to prove that the SCO intends to confront NATO. But the fact of the matter is that the evacuation of U.S. troops from Uzbekistan’s Karshi-Khanabad Air Base in November 2005 was more a result of internal policy decisions within the Uzbek government to cut off cooperation with the United States than of pressure from the SCO. That the SCO’s July 2005 Astana Summit called on the United States to withdraw troops from Central Asia does not change the fact that the base was closed due to then-President Islam Karimov’s dissatisfaction with Western criticisms and sanctions against Uzbekistan after the suppression of the May 2005 protests in Andijan. Furthermore, if the SCO was able to close the Karshi-Khanabad Air Base in Uzbekistan, it should have been able to close the Manas Air Base in Kyrgyzstan as well. Yet the base was owned by the United States until June 2014, and U.S. troops were only withdrawn after Almazbek Atambayev became president of Kyrgyzstan in 2011 and began turning the country towards Russia. Therefore, we have not seen any practical or military confrontation between the SCO and the United States or the West in the last two decades, and it is unjustifiable to evaluate the SCO through the perspective of the Warsaw Pact’s Cold War confrontation with NATO.

The second reason is that the SCO is not codified as a “Collective Security Treaty,” unlike both the Warsaw Pact and NATO. Article 4 of the Warsaw Pact, adopted on May 14, 1955, states that

In the event of armed attack in Europe on one or more of the Parties to the Treaty by any state or group of states, each of the Parties to the Treaty, in the exercise of its right to individual or collective self-defence in accordance with Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations Organization, shall immediately, either individually or in agreement with other Parties to the Treaty, come to the assistance of the state or states attacked with all such means as it deems necessary, including armed force. The Parties to the Treaty shall immediately consult concerning the necessary measures to be taken by them jointly in order to restore and maintain international peace and security.Moreover, Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty also states that

The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.But such obligations do not exist in any of the twenty-six articles of the SCO Charter, and the members have no obligation to defend one another against military aggression by non-member countries. Instead, the maximum “goals and tasks” set out in Article 1 are at most to “jointly counteract terrorism, separatism and extremism in all their manifestations,” and “cooperate in the prevention of international conflicts and in their peaceful settlement.” Therefore, unlike the Warsaw Pact and NATO, which symbolized “collective security” during the Cold War and after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the SCO is merely an organization meant to maximize cooperation and coordination between members over security and military issues.

The third reason is the SCO’s non-interventional approach toward regional and international crises. Unlike the Warsaw Pact and NATO, which have been active in regional and international conflicts and crises even outside Europe and North America, the SCO has not taken any action in this regard. A clear example of this is the SCO’s silence and inaction in the face of the three crises of Georgia (2008), Ukraine (2014), and Syria. In all three crises, in which the Russian Federation, as a founding and primary member of the SCO, intervened directly militarily, the organization’s approach was passivity or silence. This situation cannot be compared to the approach of the Warsaw Pact in the “Prague Spring” of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in 1965 or NATO’s intervention in Afghanistan after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

The SCO’s passive approach to developments in Afghanistan over the past two decades is another important factor. Although Afghanistan has been an observer member in the SCO since 2012, the organization has not been effective in dealing with developments in Afghanistan, especially since the Taliban came to power this year. At the same time, some members of the SCO, such as Tajikistan, have a completely different attitude and approach to the Taliban government in Afghanistan than other members.

The fourth reason is that, unlike in the Warsaw Pact or NATO, a number of the SCO’s Central Asian countries have engaged in military and security cooperation with the United States and NATO. As mentioned, two SCO members, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, provided the Karshi-Khanabad Air Base and Manas Air Base to the United States in support of U.S. and NATO military operations in Afghanistan. If we look at the history of the Warsaw Pact or NATO over the past few decades, we can not find such cases where a member or members of the mentioned alliance provides military and transit bases to the member countries of the rival organization.

The cooperation of Central Asian countries in the Northern Distribution Network (NDN) for the transfer of NATO and U.S. equipment from Afghanistan to Europe is another case that has not been replicated in the Warsaw Pact or NATO. In response to the increased risk of sending supplies through Pakistan, the NDN was established in 2009, and Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan cooperated closely with the United States and NATO until 2021 on transferring military equipment between Afghanistan, Central Asia, the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus, and Europe. That this close and long-term cooperation continued even after May 2015, when Russia closed one of the NDN’s military transport corridors in reaction to Western sanctions over the Ukraine crisis, is even more striking. Indeed, despite Russia’s severance of ties with NATO and the United States, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan continued to cooperate with the NDN until the complete withdrawal of NATO and U.S. troops and equipment from Afghanistan in 2021.

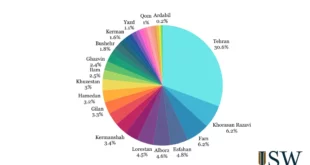

The fifth reason that the SCO is dissimilar to the Warsaw Pact or NATO is that India that was accepted along with Pakistan as members on June 9, 2017. Among the nine main members of the SCO (Russia, China, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, India, Pakistan, and Iran) and the three observer members (Belarus, Afghanistan, and Mongolia), no country has a high-level strategic partnership with the United States. India upgraded its membership in the SCO in 2017, coinciding with Donald Trump’s presidency in the United States and the development of U.S.-India relations into a strategic partnership. Therefore, India’s membership in the SCO is an important deterrent factor to the organization’s transformation into an anti-hegemonic and anti-American bloc in the framework of an “Eastern NATO” or “New Warsaw Pact.”

Although the Shanghai Cooperation Organization is a regional organization that is generally externally focused in its declarations and statements, it is internally focused in its practices and actions. Geographically, the SCO’s main focus is in Central Asia, and despite the pivotal roles of Russia and China, the organization has no role in East Asia’s many challenges, including on the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan, as well as the crises in Georgia, Ukraine, and Nagorno-Karabakh. Therefore, despite the change in Iran’s membership in the SCO, which has caused the organization’s geographical area to extend into the Middle East, it is very unlikely that the SCO become involved in the region’s many challenges. Instead, the SCO is likely to have its hands full on Afghanistan, ensuring that Central Asia remains its primary focus for the foreseeable future.

Eurasia Press & News

Eurasia Press & News